A Steady-State Defense of Arts and Culture

by James Johnston

Politicians, pundits and average people have increasingly antagonized artists to make what they do “accessible” and legitimate their trade in monetary terms. In one infamous interview on an upstart Canadian news channel, a hapless anchor attacked one of the country’s most prestigious contemporary dancers in a stunning display of vitriolic ignorance and objectionable theatrical bullying.

Politicians, pundits and average people have increasingly antagonized artists to make what they do “accessible” and legitimate their trade in monetary terms. In one infamous interview on an upstart Canadian news channel, a hapless anchor attacked one of the country’s most prestigious contemporary dancers in a stunning display of vitriolic ignorance and objectionable theatrical bullying.

The pervasive (and especially North American) notion that the arts need to be assigned a monetary value in order to be legitimized is quite simply misplaced. Arts and culture provide intangible value to society; they transcend monetary values just as they transcend history. In a future clouded with economic and environmental uncertainty, subsistence endeavors such as the arts should feature more prominently in society as we move towards a steady state.

Part of the problem is that the lines are often blurred between industrial mass culture and more traditional forms of culture. Populist commercial products that people can easily “access” will almost universally be more profitable because they are less symbolically coded. Most of us can access the thrill of a good beat or a car chase. Mass culture therefore often survives with little invested “capital,” simply because it reaches and entertains a wide audience. But what is popular and profitable is not necessarily artistic.

Ironically, it’s those so-called “elitist” art forms that are the more endangered species and in need of greater support and understanding. I’m talking about the ones that have their own intrinsic worth as reflections of identity or history, like performances of cultural dance, taiko drumming, Chopin, jazz or Inuit throat singing. These practices are not accessible to all people and will even be detestable to some, so their preservation requires that audiences put effort into understanding them. That’s why so many trained artists have no choice but to share their craft as educators.

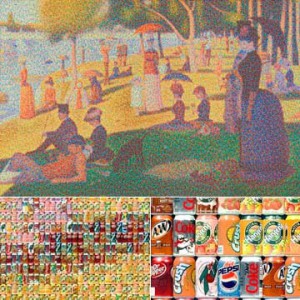

Steady-state art? Chris Jordan's "Cans Seurat" depicts 106,000 aluminum cans, the number used in the U.S. every 30 seconds.

What about modern art? I can’t defend contemporary stuff wholesale. Some of it will sink and some of it will swim. But whether it’s a play written about a small community or a graphic that reflects nothing more than a mood, such artworks are created to show us something about ourselves — something to nurture our souls. That point is lost when you persistently have to defend their economic worth because frankly, few of these things will ever be profitable in narrow monetary terms, and why should they? Unlike mass culture, these creations are not intended to be accessible to the largest possible swath of humanity! But tax dollars are certainly not being “wasted” to support artists who are often almost obsessively dedicated to what they do, few of whom apply for grants in the first place.

So, beyond monetary terms, how can we come to understand the economic role of arts and culture? We should come to view the arts primarily as a subsistence endeavor which produces enough for artists to live simply and frugally. It’s a form of voluntary simplicity much like subsistence farming or running a small business; precious little to criticize in a steady-state economy. These endeavors don’t demand much: they don’t add to the debt burden, and they don’t consume a huge volume of material or financial resources as they go about enriching our lives. Artists also often live in affordable geographic areas that are dilapidated (like inner cities) and in need of the kind of vibrant renewal the arts provide. Artists in fact contribute far more to society than they consume.

Last but not least, what about the artistic product itself? If the product is not necessarily profit-producing, what legitimizes its worth? Some would argue that only endurance can legitimize the artistic product. As an impulsively self-gratifying, increasingly narcissistic society, the idea that we can only come to know something in time is a hard reality to accept. But some of these curious, inaccessible modern works will indeed become classics in time. Think of the 20th century works of Beckett or Joyce. They still aren’t really accessible in that you have to work at understanding them, but they are remarkable creations and have to be respected for the way they hold a mirror to society (and don’t narcissists need mirrors?).

It is the responsibility of both the artist and the average person to understand the socioeconomic contributions of the arts. Understanding and enjoying the arts is a lifestyle choice that will sometimes require us to get off the couch, step away from the television and into art galleries, music and dance halls, places of worship, and libraries. The process has the positive side effect of building stronger relationships and communities. Not everything we experience will be perfect (and some of it may be bad), but that’s part of the adventure… because every once in awhile, we will come across something that changes our perspective a little.

And there’s never been a better time to start thinking, seeing and doing things a little differently.

Why does the “artistic product” need to be legitimized?

The intrinsic value of art is only accessible to the artist. Its value derives from the opportunity it provides to artists to express themselves. Any “legitimization” (meaning, I presume, that someone other than the artist is willing to pay for the thing) has more to do with the status seeking of the buyer (“See how much money I can afford to pay for things that I cannot eat, wear, or take shelter under!”) than with any intrinsic value.

Art may have (non-monetary) value for others, insofar as it may provide pleasure in the perceiving, or perhaps some widening of perspective.

But, the artist who creates “artistic produce” for the principle purpose of exchanging it for money so that they needn’t support themselves by the “sweat of the brow,” is exploiting their fellow men only to a lesser degree than are the captains of industry and presidents of banks who can afford to pay for their stuff.

I get the feeling, Gordon, that you are one of those people who just doesn’t understand the real value of art and what is it about, seeing and showing things in a new light or perspective. It is not just of value to the artist. And as someone once said, “It has always been the job of the artist to challenge the status quo.” Art is important in a society to impel growth….not quantitative growth but qualitative….which, as anyone who is a Steady Stater should know, is more important. And by the way, as an artist….ART IS WORK and it can be incredibly hard work.