The Connection Between Population, Income, and Health

by Max Kummerow

For hundreds of years, economists have debated whether population growth is good or bad. Malthus said exponential population growth increases labor supply, so wages fall until starvation, war, or plague stops growth in numbers. Marx said capitalism causes poverty and hunger, so population growth is good, because “every stomach is born with a pair of hands”, bringing revolution and justice closer.

Nearly 200 years later, Garrett Hardin and Julian Simon were still debating the same question.1 Hardin insisted that individuals’ decisions whether to have children without considering the tragedy of the commons could add up collectively to overpopulation and environmental catastrophe. Simon responded that human ingenuity is “the ultimate resource”. Shortages lead to new inventions that benefit the collective whole. Simon cited 300 years of falling commodity prices, indicating less scarcity, not more, despite population growth from 500 million to 5 billion.

The debate is ongoing, with most mainstream economists supporting population growth, while ecological economists warn about “overshoot” and collapse as the earth’s resources are used up.

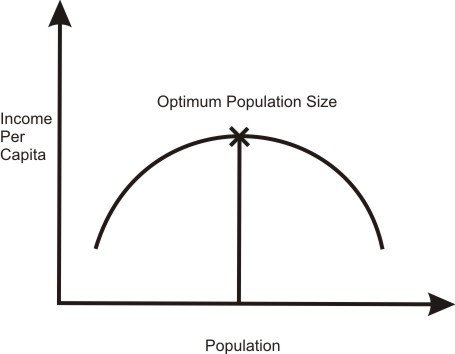

One reason this debate has taken so long to settle is that both sides are right. Economies of scale and technological progress mean bigger cities, businesses, machines, and farms can often be more efficient, raising economic output. But with too many people, there are negative externalities—pollution, traffic congestion, crowding, and resource shortages. Above optimum size, cities, businesses, machines, and farms get less efficient.

Optimum population size maximizes incomes.

The ideal level of population depends on preferences. How rich do you want to be, and what lifestyle do you wish to lead? Do you want to live in a McMansion (or even a “regular” mansion)? How much space should be reserved for other species? How much space should be reserved for the functioning of ecosystem services such as water purification, carbon sequestration, and nutrient recycling? Do future generations count in these calculations? How much traffic congestion can you tolerate? These questions aren’t asked often enough by sufficient numbers of people.

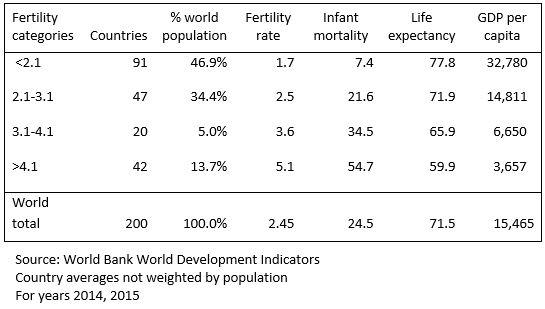

However, data already exists to settle the long-running economists’ debate about population growth’s effects on incomes and health. Countries that achieved “demographic transitions” to less than 2.1 children per woman enjoy dramatically better economic and health outcomes. The table below compares the most relevant figures associated with four levels of fertility.

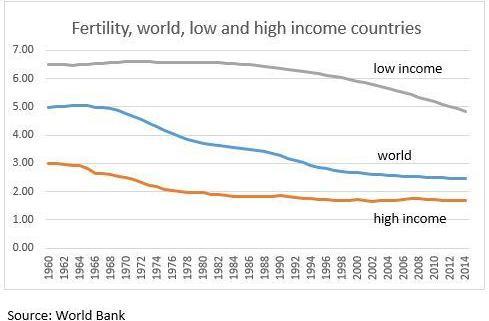

In 2015, the low-fertility countries (<2.1) had average incomes nine times higher than those of high-fertility countries (>4.1). Infant mortality was 47 per 1,000 births lower, and life expectancy was 18 years greater. Of course, many other factors determine incomes and health outcomes: education, natural resources, health care systems, rule of law, improved status of women, and other factors. But the constellation of factors that helps countries prosper strongly correlates with low birth rates. Persistent high fertility rates leave countries treading water, while lower fertility rates make improving the other variables easier. The graph below shows falling global fertility but the substantial discrepancy in fertility between low- and high-income countries..

Fertility rates for world, high and low income countries, 1960-2015

When birthrates fall, a country faces less tax burden because there is less need to expand infrastructure, education, and health care. A “demographic dividend” comes from increased labor force participation by women, more educational expenditure per child, and freeing of capital for investment. Slower growth in population moderates demand and prices of scarce commodities such as land, housing, food, energy, and other commodities.

These effects can also be seen at an individual family level. USDA estimates the cost to raise a child to age 17 at $233,000.3 Women who delay childbearing to get more education have higher lifetime earnings. If parents choose to have fewer children, they can have significantly improved standards of living and higher retirement savings. An only child will probably inherit more than four times as much as a child in a family with four children. In a subsistence farming community, a four-child family-size as the norm halves land per capita every generation. One child doubles per capita family land.

These recent data should end the long-running economists’ debate. In our present world, having fewer children improves economic and health outcomes for individual families and for countries. As the world moves toward steady state economies, reversing population growth improves lives for everyone.

In summary:

- World population still grows by 80 million per year, headed from 1 billion in 1800 to 10 billion by mid-century.

- Nearly half of the world’s countries have accomplished “fertility transitions” to birthrates that, if continued, would begin to decrease populations after the fifty years of further growth that results from “population momentum”.

- Increased efforts to promote family planning in countries with persistent high birthrates will be required to complete the transition to a steady-state population.

Footnotes

[1] They were literally debating. I attended one of their debates, moderated by a history professor in Madison, Wisconsin in 1983.

[2] World Bank’s World Development Indicators. Income is a “purchasing power parity” comparison.

[3] https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2017/01/13/cost-raising-child

Max Kummerow is a retired business school professor and population activist who researches demography, ecology, and economic development. He has presented papers at ESA, PJSA, NCSE, PAA and EAERE meetings showing the benefits of accelerating the world’s stalled demographic transition toward lower fertility rates.

Max Kummerow is a retired business school professor and population activist who researches demography, ecology, and economic development. He has presented papers at ESA, PJSA, NCSE, PAA and EAERE meetings showing the benefits of accelerating the world’s stalled demographic transition toward lower fertility rates.

Good insights. This reminds me of when I first read about “K-selected species” vs. “R-selected species”, where K-selected means low numbers of offspring, but the parents invest a lot of time and resources into each offspring. R-selected means you just have tons and tons of offspring, like field mice or mosquitoes, and some of them survive.

It seems to me that human societies leaning more to the K-selected side of the spectrum are clearly healthier and happier. Overall it does seem that a K-selected type approach to population fits hand-in-glove with the model of a steady state economy. I reckon humanity will make that transition, it’s just a question of whether it’s mostly voluntary, or involuntary (picking up the pieces after a growth model fails).

I’m cautiously optimistic it will be more of a voluntary transition than not, but it’s going to be a close one.

Thank you, Max and CASSE. I particularly liked the difficult questions you raised in the section copied below:

“The ideal level of population depends on preferences. How rich do you want to be, and what lifestyle do you wish to lead? Do you want to live in a McMansion (or even a “regular” mansion)? How much space should be reserved for other species? How much space should be reserved for the functioning of ecosystem services such as water purification, carbon sequestration, and nutrient recycling? Do future generations count in these calculations? How much traffic congestion can you tolerate? These questions aren’t asked often enough by sufficient numbers of people.”

As one idea to help advance the pursuit of a voluntary transition to sustainable human populations in every country, please consider joining and supporting the increasingly popular campaign seeking a multilateral treaty on population growth – more information here: http://www.scientistswarning.org/population-the-elephant-has-left-the-room/.

Sincerely,

Rob

Rob Harding

Sustainability Communications Manager, NumbersUSA

Member, International Society for Ecological Economics

Fellow, Royal Society of Arts

rdharding2@gmail.com

Thank you Rob Harding. You have been working on the most important question facing people and the planet. I salute you. Kummerow’s article is also excellent.

“Overpopulation actually occurs

at a lower point with a higher

standard of living.”

https://npg.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/OverpopulationandOverconsumption-revised2013.pdf

Although I definitely agree that lower human population is desirable for many reasons, I think your post conflates correlation with causation. Populations do not become rich because they have fewer children, they have fewer kids because they have become rich.

It should also be kept in mind that the countries with high population growth have little to do with the global environmental problems we are facing, particularly climate change from greenhouse gasses. Virtually all of the excess CO2 in the atmosphere was put there by the rich. As Mike Hanauer noted above, the only “overpopulation” we need to worry about is that of those who are affluent.