Attempting a “SlowDown” in Stafford County

by Dave Rollo

Stafford County, Virginia, is one of the oldest counties in the United States. Unsustainable development threatens its agrarian culture and residents’ quality of life. Uniquely, the local government has tools to measure the negative impacts of growth. However, they continue to incentivize big-box commercial and retail development. They are changing zoning, extending infrastructure, and failing to increase impact fees. The county’s supervisors are serving developer interests, and a developer currently serves on the planning commission. Residents have formed the group SlowDown Stafford to tell local officials that enough is enough.

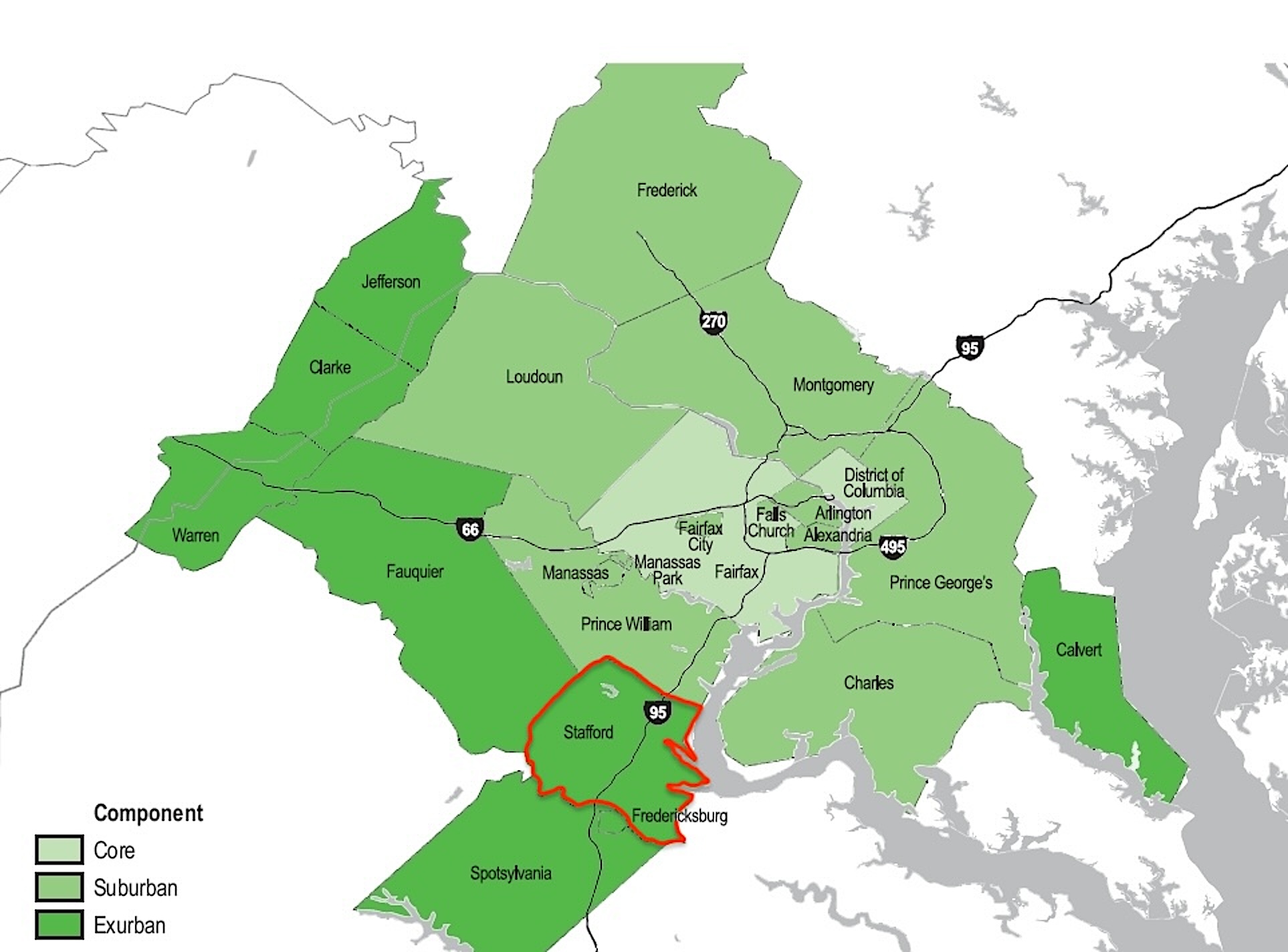

Exurban sprawl from the nation’s capital, with Stafford County on the front line. (Public Domain, Bureau of Labor Statistics)

Stafford County was established in 1664, just thirty years after the first counties (known as “shires”) were created by the colony of Virginia’s House of Burgesses. The county is the boyhood home of George Washington. For hundreds of years, residents enjoyed an agrarian culture and a population of less than 10 thousand, despite their proximity to the nation’s capital, only 25 miles to the north. But since the 1950s, Stafford and other counties surrounding DC have seen bursts in population, coinciding with connections to the Interstate Highway System. Stafford County’s population of 170 thousand is growing by over 60 people per week.

The county is bisected by I-95, the East Coast’s main corridor and one of the busiest highways in the United States. Traffic volume on I-95 near Fredericksburg, an independent municipality on Stafford County’s southern border, clocks in at over 120 thousand car trips per day. This stretch of the interstate was ranked the worst traffic hotspot in the nation.

I-95 and its connections to the Washington, DC, Beltway (I-495) facilitate sprawl, transforming forests and farms to commuter suburbs. As a longtime Washington Post columnist wrote in 2006, “It should be obvious, even to the most determined of local boosters, that we won’t be able to grow our way out of the problems of inadequate transportation infrastructure, the overcrowded schools, the overtaxed local budgets.”

For decades, experts have cautioned that growth would adversely affect Stafford County by way of excessive traffic, sprawling strip malls, loss of farmland, and rising costs for taxpayers and ratepayers. Political efforts to push back against destructive growth have been half-hearted. But now, there is a mounting groundswell of citizens advocating for change. Will county leaders heed their calls to slow down growth?

Growing Pains

Washington, DC, experienced the fastest population growth of any urban region in the country in 2024. Moreover, the COVID pandemic led to over 60 percent of employees in the region working either fully or partially remote. New work requirements for federal employees have affected this statistic. But generally, the number of remote workers in the United States has doubled over the past ten years, revealing a lasting trend.

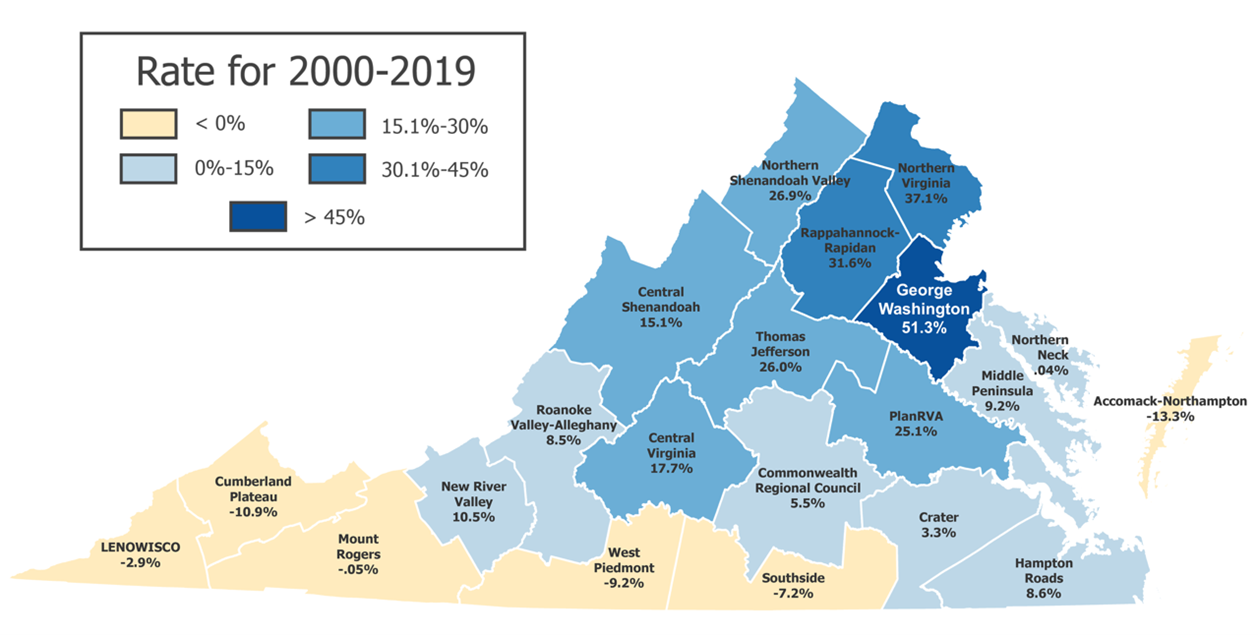

Population growth rates for the planning districts of Virginia. (map by @Arterial Mapping, data from U.S. Census Bureau)

This workplace shift has placed greater growth pressure on exurban counties like Stafford. Consequently, the county’s population growth rate is more than 2 percent per year. At this rate, Stafford County’s population would number more than a quarter of a million by 2050.

In Virginia, planning district commissions are designated for interlocal government cooperation on economic development, transportation, and environmental planning. Alongside three other counties, Stafford County belongs to the George Washington Regional Commission. This region has experienced a population increase of more than 50 percent over twenty years, more than any of Virginia’s other 23 planning districts. As Washington Post columnist Steven Pearlstein forewarned almost 20 years ago, “the region finds itself at those tipping points in the growth process, where the next increment of desired capacity requires a huge, upfront investment.”

Comprehensive Planning: The Good and the Bad (and the Expensive)

Stafford County has a comprehensive plan, created in 2016 and updated in 2021. It recognizes some key concepts related to controlling growth but falls drastically short on others. The plan acknowledges the problem of sprawl and the need for compact form and zoning to reduce car travel. It uses a metric called “level of service” to track the impact of growth on county infrastructure and services.

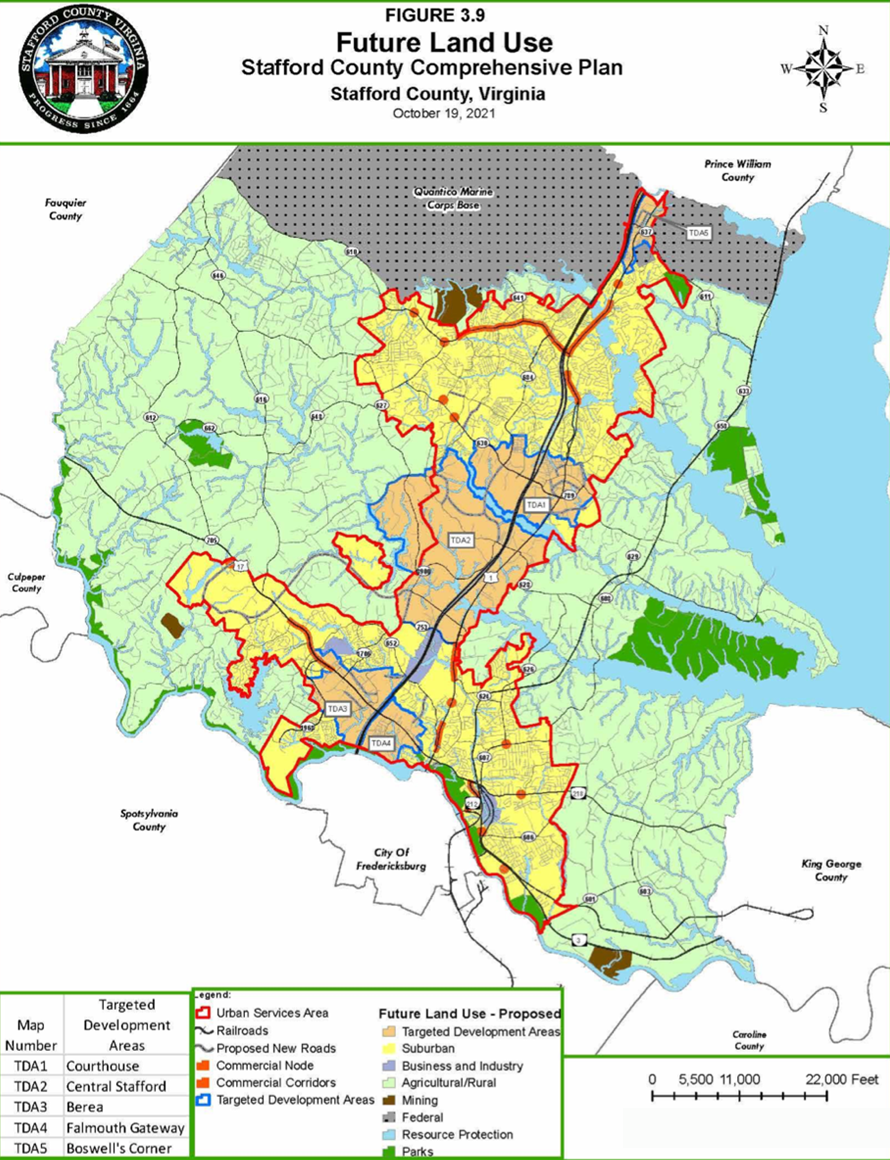

Most of Stafford County’s protected land is contained within the Quantico Marine Corps Base along the county’s northern border. (Public Domain, Stafford County Comprehensive Plan)

In the comprehensive plan, the county also does a good job of mapping natural resources, such as forests, streams, and wetlands. The plan employs an Urban Services Boundary (USB), too, with the intent of containing high-impact development. Examples include street expansion, water and sewer service, and sanitation.

Stafford County’s comprehensive plan acknowledges rampant development and includes tools to gauge it. Despite this, the plan calls for a sprawling development pattern within the USB. The USB itself is a broad, contiguous expanse encompassing the entire length of I-95. The plan surrenders approximately 80 square miles to intense development. That’s about a third of the county.

Intense development within the USB is further prescribed in the companion Economic Development Strategic Plan. The first two goals laid out in the plan are:

- “Continue to expand business growth and employment, becoming a more progressive center of employment within the greater Washington DC Metropolitan Area.”

- “Accelerate infrastructure upgrades serving critical commercial and industrial sites.”

Other goals are built on the assumption that more development will improve “quality of life.” The plan is to facilitate this by expediting development approval processes, thereby lowering taxes on businesses (Goal 10).

Thus, Stafford County’s planning documents provide contradictory guidance: Control and contain growth, but accelerate it, with quality of life to follow. Invest more in infrastructure within a large interstate-development zone. Keep business expenses low at ever-increasing public expense, and residents will reap the benefits.

Many residents of Stafford County disagree with this vision of quality of life. Formed in 2024, SlowDown Stafford is a grassroots group with over 1,200 members. They question the plan for their county’s future and aim to hold their representatives accountable.

For SlowDown Stafford, an important first step is to convince the county government to stop subsidizing the growth that is degrading their quality of life, not enhancing it. Members want to keep their county great, not watch its greatness transform into an unrecognizable extension of Washington, DC.

Citizens Respond to the High Cost of Growth

The Stafford County Comprehensive Plan acknowledges that growth comes with costs. These include the costs of expanding infrastructure, such as roads, schools, and stormwater and sewage treatment. These costs also include county services such as public safety, social services, public works, and education. That the county calculates these costs is commendable. However, the plan fails to address less obvious costs of growth. These include air and water pollution, noise, traffic congestion, and the erosion of farmland, forests, and wildlife habitats.

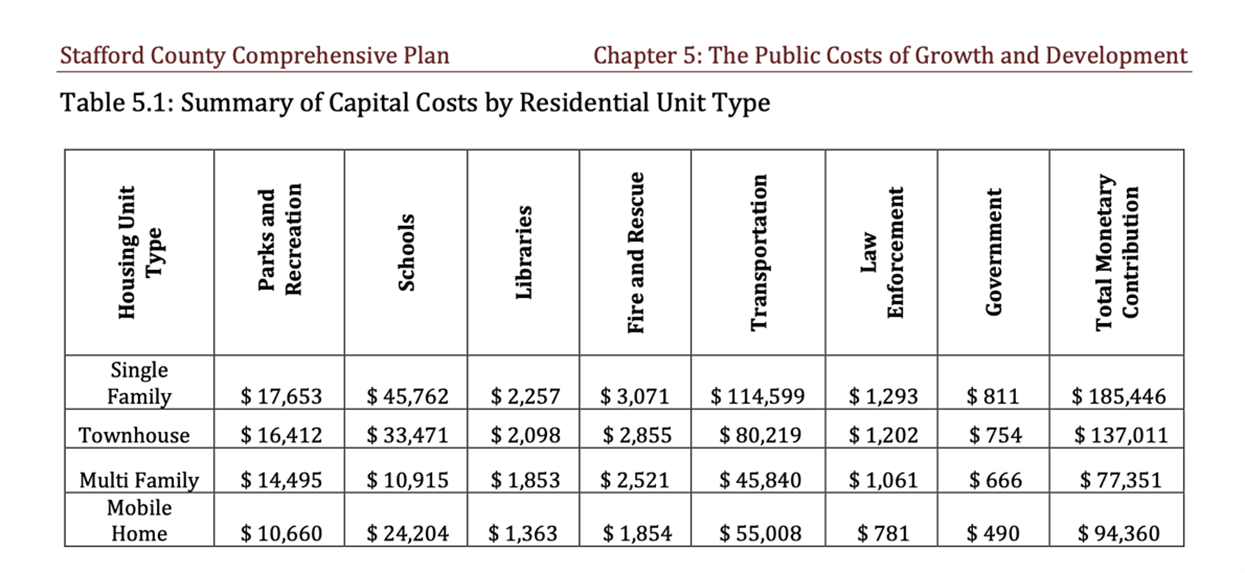

According to Joe Brito, a SlowDown Stafford member, the revenue accrued from development fees is woefully inadequate. For instance, the 2020 estimate of the capital cost for schools is over $45,000 per single-family dwelling. It’s likely over $60,000 today, accounting for inflation.

Calculations of the capital costs associated with different types of new residential housing. (Public Domain, Stafford County Comprehensive Plan)

Recently, the county approved four housing developments totaling a thousand new houses. If our $60-thousand-per-dwelling estimate is correct, these developments will entail an expenditure of $60 million, much if not all of which would be financed by debt.

Brito pointed out that those one thousand houses will collectively only pay $5 million in real-estate tax per year. If all those taxes went toward the school (they will not), it would take the county at least twelve years to pay it off. (And probably longer, including the interest payments.)

Schools are just one example of public costs. Although the county recently raised fees for transportation, many other infrastructure and services remain underfunded. For example, road infrastructure, parks and trails, and public safety are falling behind as growth continues.

Referring to the Stafford County Board of Supervisors, Brito poses the question: “The supervisors have the authority to raise the fees….What are they waiting for?”

Rampant Rezoning for Buc-ee’s and Beyond

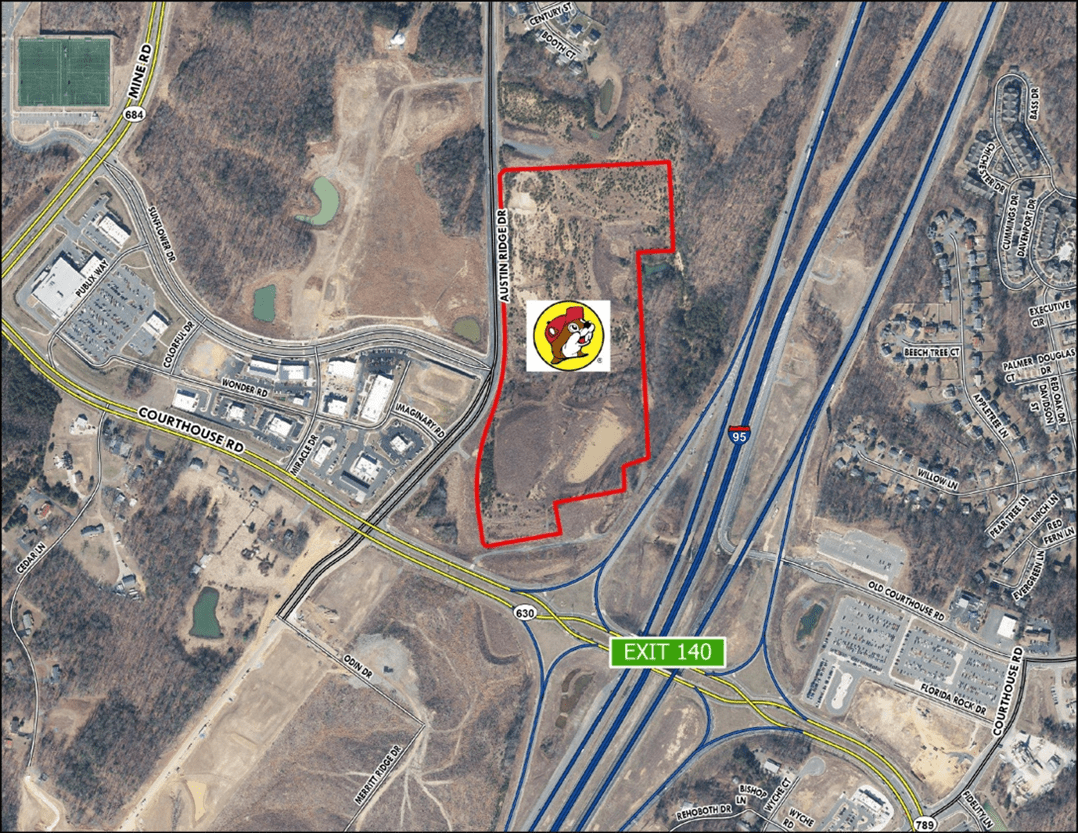

County government also accommodates big development by rezoning. They have proposed rezoning a parcel adjacent to I-95 to accommodate a 1.5-million-square-foot Buc-ee’s. This would be an immense travel center replete with restaurant food, 120 gasoline pumps, and convenience-store goods. The county planning staff supports a conditional-use permit. Conditions include roadway improvements and the delineation of a resource protection area for a wetland adjacent to the development site.

Buc-ee’s is just one example given by SlowDown Stafford of the county government’s failure to keep the county great. (map by author, data from Stafford County Planning Department)

SlowDown Stafford has organized against the rezoning petition. They have apprised their members and local government of the negative impacts of mega-convenience retailers on employment, neighboring residents, and the environment. These include loss of nearby home property values, groundwater contamination from storage-tank leakage, and air pollution from benzene and other toxic compounds. Over 2,200 people have signed an online petition in opposition to the Buc-ee’s proposal.

To Albert Undercoffer, the founder of SlowDown Stafford, the county does not adhere to the spirit of the comprehensive plan, which would limit development via prudent zoning. “One major problem with the supervisors is that they rezone everything. They don’t even follow the existing code or direction from the comprehensive plan,” said Undercoffer.

Despite public outcry, the government continues to grant exceptions to the zoning code, albeit with sometimes narrow margins. “Some of the supervisors are better than others, but the majority award the rezone and often follow the direction of the Planning Commission.”

Getting the Growth Brakes on the Ballot

Stafford County is at the midpoint of its comprehensive plan’s lifespan. The government has taken some measures, such as establishing the USB, to address incessant growth. However, services and infrastructure are lagging. The county government is passing the costs of development on to the public in their attempts to catch up with past urbanization.

The 2026 budget topped $1 billion for the first time and included a 3-cent tax-rate increase. Much of the tax increase in recent years comes from increases in assessed home values (for example, a 21 percent increase in 2022). But as the public’s taxes go up, tax breaks are given to large-scale developments. A particularly egregious example is data centers, which receive a rate of $1.25 on $100 of assessed value, as opposed to the standard business-equipment rate of $5.49 per $100.

The county can disincentivize development by increasing impact fees and refusing to rezone land for detrimental development. SlowDown Stafford is rallying its members to oppose some of the most egregious rezoning petitions, including for data centers, housing tracts, and big-box commercial developments.

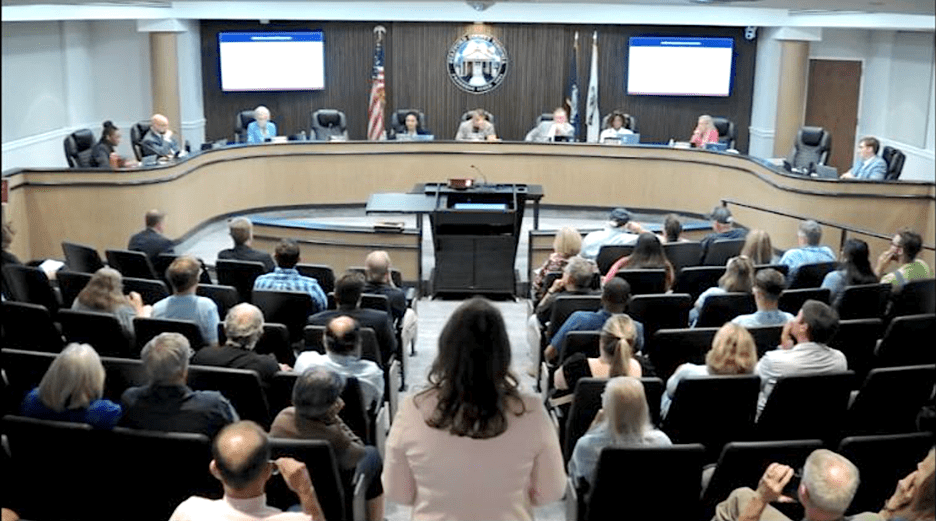

A Stafford County Board of Supervisors meeting in early August of 2025. (SlowDown Stafford)

Will the Board of Supervisors respond to the mounting alarm over the public costs of growth? Albert Undercoffer is doubtful that the current officeholders, or the crop of candidates for the next election, will protect the county against development interests.

There have been some notable exceptions. In 2021, a historic vote of the rural zoning districts reduced new-home density from one per three acres to one per six. Reducing intensity of use—aka “downzoning”—is controversial. It is viewed by some as a “takings,” reducing the value derived from a property. The downzoning decision passed by a single vote.

Stafford County communities are in dire straits, with public facilities falling far behind, even as new developments arise. With sufficient political will, the county government could deploy a moratorium on development. This would allow the county to catch up with its provision of services. The government could also update the comprehensive plan and zoning code, to downzone areas within the USB or rescale the USB to a more reasonable size.

The warnings made nearly 20 years ago about growth in Stafford County were not heeded, though Stafford County made partial attempts to reduce the negative impacts of growth. What is different today in the county is a wealth of activated citizenry, attending meetings and holding elected representatives accountable. Perhaps candidates in the Fall 2025 election will sharpen their focus on keeping the country great.

Dave Rollo is a policy specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

Dave Rollo is a policy specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

It’s interesting to read how those in positions of power don’t follow the rules or change the rules to accommodate developers instead of doing what would be in the interest of the local citizens. I know of a situation in my local community in Christchurch New Zealand where our local council has broken its own regulations and caused stress for a law biding householders. We must do better. Thank you for all that you do at CASSE.

Neoliberalism is not about governments pulling back, but about governments reconfiguring the economy – changing the rules of the game – to serve the interests of chrematists. Our political institutions are designed to do this – after all, they were created long ago by predominantly wealthy, white, male, property owners (chrematists) – while the masses pretend they live in genuine democracies (a con-trick still being swallowed by the masses).

I don’t envisage our problems ever being solved within our current political framework (institutions). I don’t know the solution. There has never been a truly democratic society operating on oikonomic principles since the advent of agriculture 11,000 years ago. Communism was attempted but failed because it rejected the functional requisites of a modern, complex, and technologically sophisticated economy. Neoliberalism (institutionalised chrematistics) also fails (eventually) because it sows the seeds of its own destruction. It has failed many times before (i.e., reaches the end of its relatively stable life) and has always resulted in disaster. It ran its course in the early 20th century and led to two world wars and a Great Depression in between.

In the past, ecosystems and some useful social institutions were sufficiently intact to recover. But the same political institutions remained. The WW1-GD-WW2 mayhem trimmed the wealth and power of the rich and powerful enough for the Western world to come the closest humankind ever got to democratic oikonomia (outside hunter-gatherer societies). Thirty years of relatively equitable and public goods-focused growth (post-WW2 period) produced some of the most contended society’s ever (the USA a bit of an exception because of civil rights issues and the most unequal distribution of income in the West).

Continued: Unfortunately, the growth of this period was based almost entirely on fossil fuel use (still is!) and growth for growth’s sake. It should have been growth that was based on fossil fuels (an Industrial Society) with the aim of transitioning to a SSE based on renewable energy (a Post-Industrial Society). The transition should have been completed by now. This didn’t happen. Hence, the period was still very chrematistic-like (non-oikonomic). So, we keep going through the chrematistic cycle of collapse-recover-collapse, with some semblance of oikonomic organisation during the initial stages of the recovery phase. The chrematists eventually regain some of their lost wealth and exploit the chrematistic political institutions to their advantage, as they have been doing since the late-1970s/early-1980s (when neoliberalism took hold).

The problem is that the next collapse (perhaps not far away) will leave us with 8+ billion people on Earth, collapsing social and ecological systems, and a climate system no longer amenable to most existing species. It won’t be a world that can easily recover, let alone put in place an oikonomic society based around a SSE. And it won’t be a world that puts in place the latter if our current political institutions remain intact. Political institutional reform will be (and is) as important, if not more important, than any economic, social, or ideological (belief in the ‘good’ life) reform.