Growth of an Economy, Death of a River

by Amelia Jaycen

“Low” water levels are becoming the norm in Lake Mead (the Colorado River impounded by Hoover Dam). (CC BY-SA 4.0, Carchiav)

The Colorado River has a simple math problem: More water is taken out than nature refills every year. The gap between the two is also widening. Every year, an increasing amount of water is taken out of the Colorado River, as demand for water increases across the arid American West. Meanwhile, every year less water is available in the river and its tributaries as climate change and other manmade stressors cause imbalances in natural systems.

Across seven states, 40 million people rely on this 1,450-mile river for drinking water, but it can no longer sustain the demand. The Colorado River Basin has been in severe drought for a quarter century, since 2000. Now, the drying up of the river, along with the depletion of groundwater, is so dire that emergency measures may be needed. Millions who rely on the river may be forced into extreme changes in the next 24 months, amounting to a scenario all are unprepared to face, from national regulators to local water utilities.

It’s a bad scenario created by a complicated history. The way of the future is going to depend on whether we can reduce growth across the West and see the river for what it is, not what we demand from it.

A Complicated History

In 1922, representatives from seven states met to divide the Colorado River into upper and lower basins and allocate how much water each basin can use each year. Based on then-current numbers for river flow and human needs, 7.5 million-acre feet (MAF) were allocated to the upper and lower basins per year. This was later translated into specific percentages for each individual state in 1948.

Since the 1922 Colorado River Compact, a complex of laws, agreements, allocations, treaties, regulations, court decisions, and contracts has unfolded. This web of human decisions is collectively known as the Law of the River. It strays far from the physical laws that determine how the river would naturally function.

For example, the Law of the River includes the 1964 decision assigning regulatory control—and the accompanying web of water infrastructure projects that siphon water off the Colorado—to the Bureau of Reclamation (BOR).

But while cities, counties, states, and the BOR are busy with the complicated management problem to keep infrastructure running and continue to allocate water rights to more new users, the water has been quietly running out. Essentially, everyone is planning for future uses of water that simply isn’t there.

Each month, the BOR releases 24-month studies on the Colorado River Basin with a range of short-term projections for best, medium, and worst-case scenarios. Their August 15, 2025, report calls for reductions of water to states in the basin, including an 18 percent reduction for Arizona, which seems impossible in one of the fastest-growing states. It calls for a 7 percent reduction in Nevada and a 5 percent reduction in New Mexico.

But a team of water researchers is concerned that the BOR studies may miscalculate “the most likely impending hydrologic reality.” The analysis is authored by Jack Schmidt, director of the Center for Colorado River Studies at Utah State University and former chief of the Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center, and Anne Castle, former U.S. Commissioner of the Upper Colorado River Commission and former Assistant Secretary for Water and Science at DOI, and their colleagues.

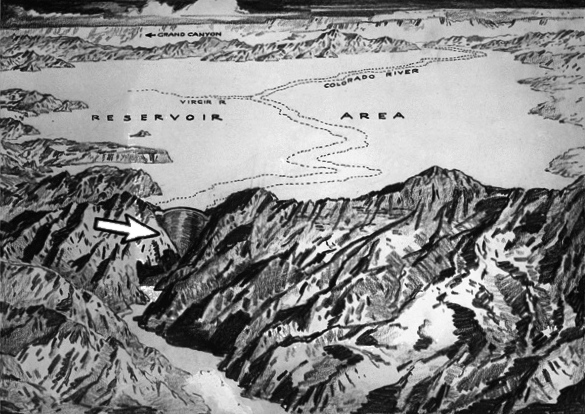

A 1921 sketch of Hoover Dam. (CC BY 4.0, Los Angeles Times)

The report’s authors attempt to cut through the noise and analyze the “realistically accessible storage” in reservoirs and determine what might happen in the next 12 months if the river’s natural flow is similar to this year’s. They determine that avoiding dangerously low water levels and operational complications (inability to use Hoover Dam, for example) in 2026 and beyond would require “immediate and substantial reductions in consumptive use across the basin.”

In the Law of the River, several key agreements expire in 2026, and all parties, including tribes, states, and the BOR are scrambling to devise new agreements to guide the use of the river going forward. But the experts note that the new agreements may have to be dramatically different from what anyone can imagine today, with a dry basin, low reservoirs, and a river in peril.

While they scramble to come up with new agreements, the water continues to run out.

Too Many Straws

Across the Colorado River Basin, there are 15 major dams and 46 trans-basin diversion projects to siphon the river’s water across seven states to feed development projects, agriculture, and human water supplies. For example, the Central Arizona Project (CAP) is a 336-mile canal that siphons off enough water from the Colorado River to supply more than 80 percent of Arizona’s population.

But who’s the biggest user? Big Ag. Agriculture is the number one user of Colorado River water by far, using 52 percent of the water. Meanwhile, seemingly endless development projects across the West use plenty. Towns, cities, and counties seem to want to continue the boom, water shortage or not.

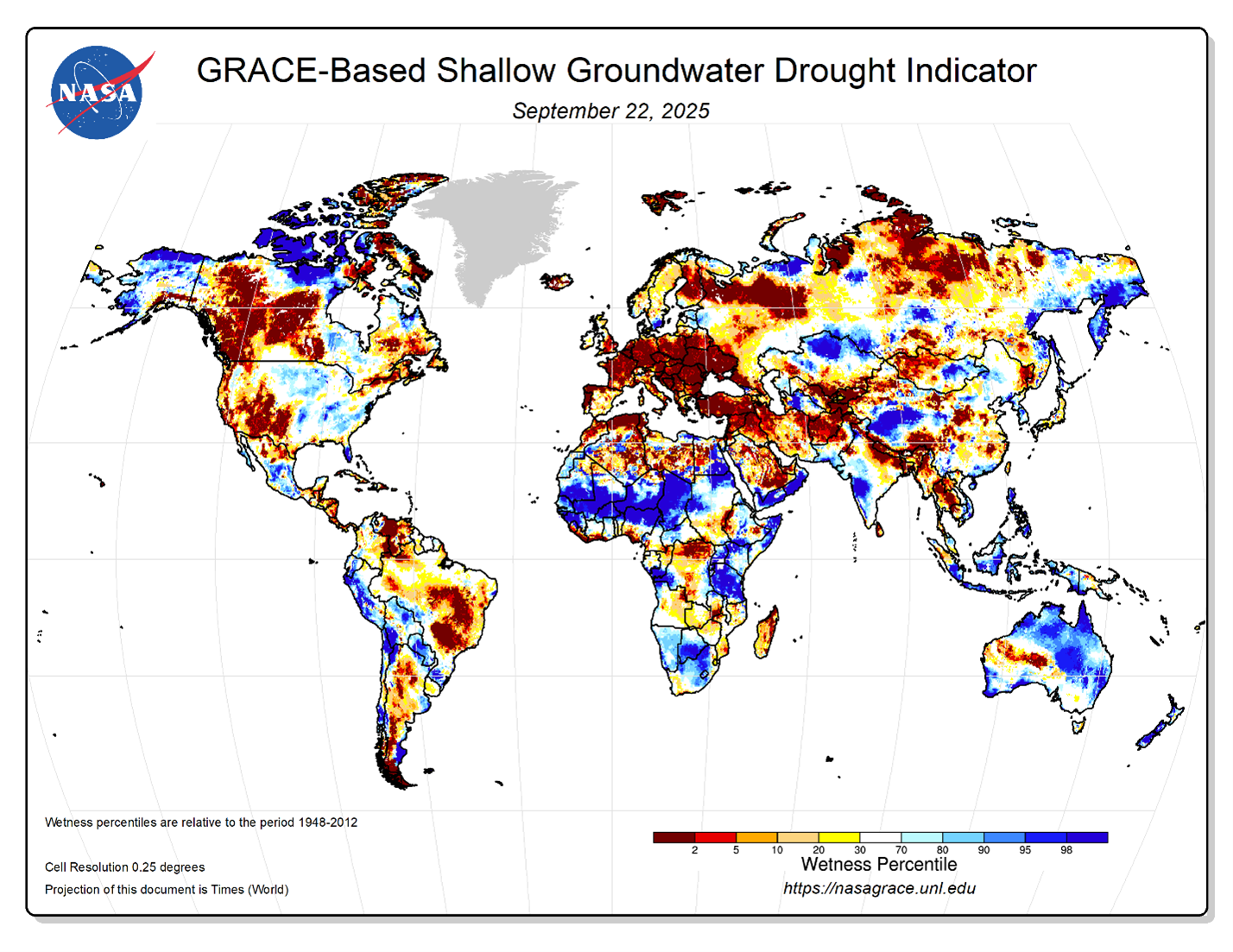

NASA’s GRACE satellites capture groundwater levels, indicating drought risks. (NASA GRACE)

While the river runs out of water, groundwater also is decreasing in the Colorado River Basin, across the United States, and worldwide. The water cycle in arid states is changing, with different rates of precipitation, stream flow, snow melt, and evapotranspiration, the movement of water from land and plants to the atmosphere. The Ogallala Aquifer in the Great Plains is steadily dropping every year, and midwestern states have been warned for years of its steady decline.

In 28 major cities across the United States, economic extraction of water is causing groundwater supplies to shrink, causing subsidence, or sinking, on 20-65 percent of the land. This puts roads, bridges, and electrical infrastructure at risk. NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) uses space-based satellites to provide a detailed look at groundwater depletion and the resulting risk of drought around the world. It reveals a rapidly drying planet.

The United Nations “World Water Development Report 2024” indicates about half the global population experiences severe water scarcity for at least part of the year. It identifies water stress as a potentially destabilizing factor that could lead to a range of violent conflicts, poverty, and disease, threatening social stability in water-stressed areas.

The Reality of Limits

The first law of holes is, if you find yourself in one, stop digging.

In other words, the river and its natural refilling sources are running low, and everyone has to stop using so much. Not next year. Immediately, experts like Schmidt and his colleagues say. Any further growth and demand on the river is like signing a death certificate of the Colorado River.

NASA satellite imagery showing drought in the Colorado River Basin. (Public Domain, MODIS Land Rapid Response Team, NASA GSFC)

Residents of the Colorado River basin are now living in an era of limits, facing extreme water shortages due to overuse.

Humans can’t force aquifers to fill up or rivers to flow more, no matter how much we need it. The only thing we can do is to reduce the demand side of the equation, or face a bleak future in which there is no water in the tap, much less for new developments or exporting.

In the Colorado River Basin, every new, additional use of water means someone else across the basin will have to decrease their use. But no one wants to give up their water, and conflicts are bound to rise in this scarcity scenario. Ideally, everyone would reduce their use, thereby reducing growth and bringing the river back closer to its natural balance.

“The River recognizes no human laws or governance structures and follows only physical ones,” Schmidt said. He notes that “it may be difficult, if not impossible for basin states to implement immediate, additional reductions in use,” and the onus is on the DOI to take immediate action and implement laws to limit use.

While basin-wide watershed management is needed to provide oversight among states, tribes, rapidly growing cities, and federal regulators, water users and managers are too siloed. Most don’t understand the complex system of canals and infrastructure siphoning water off the Colorado River and how their decisions affect the rest of the basin.

As it stands, it’s unclear if any of the parties, including the federal regulatory body tasked with making post-2026 plans for management across the Colorado River Basin, are fully aware of the drastic measures that need to be taken. Even in the midst of scarcity that will alter how everyone survives in the future, many who depend on the river are handicapped by tunnel vision. They lack system-level awareness of where water comes from, the natural processes that feed rivers and canals, and why they are draining beyond recovery.

Restoring the Natural State of Rivers

The math seems simple: 100 percent of the Colorado River’s water is being used, and there is no more room for growth. Yet new developments and sprawl, along with agriculture, are demanding more water. Almost all the river’s water is siphoned off into canals, so it can’t maintain its natural flow. The Colorado River Basin is like a checkbook completely out of balance, economically and ecologically.

For a long time the American West has been dipping into savings (reservoirs like Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the two largest in the United States) to make ends meet. We’ve counted on natural reserves (groundwater and snowpack) to refill the account and cancel the deficit. But we’ve reached the point where there is little left of reserves and savings, and no guarantee of replenishment.

Grand Canyon of the Colorado River. (CC BY 2.0, Wolfgang Staudt)

Colorado River scientist and activist Gary Wockner thinks that rivers should have rights to exist, not be completely decimated to the point of extinction. “The rivers don’t have any rights to exist almost anywhere in the Rocky Mountain West,” Wockner said. “Laws were designed to get water out of rivers, not keep it in.”

Wockner is executive director of Save the World’s Rivers, a water protection group that has a program to protect the Colorado River in particular. The group has a new initiative working on assigning rights to rivers as a foundation for robust protection. He wants to give nature a seat at the negotiating table to drive better overall decision-making for the long-term health of rivers and people. Assigning rivers rights could help re-focus human populations on conserving rivers’ healthy natural state instead of focusing on what we can get out of them, down to the very last drop.

Wockner’s group has had several successes in Colorado. They’ve examined how local ordinances could do more to help people understand what the day-to-day realities of water conservation might look like. Their model “Rights of Nature Ordinance and Resolution for Municipalities” has been adopted by municipalities in the Boulder Creek Watershed, the Uncompahgre River Watershed, and the Grand Lake Watershed.

Wockner also touts impact fees, paid by water users to cover the impact their use has on rivers. Such fees help people become more cognizant of the big picture and more responsible for their actions.

Other helpful actions for municipalities would be disallowing irrigated grass in developments, requiring xeriscaping and drought-tolerant landscaping, and other forced water conservation measures to ensure river protection.

“If counties can work to constrain growth, it will help protect rivers,” Wockner said.

“Controlling growth is the biggest thing you can do.”

Amelia Jaycen is a program manager at CASSE.

Amelia Jaycen is a program manager at CASSE.

Excellent article. Education seems to be the best way forward. The goal could be the following quote from The People’s Commission on the Water Sector U.K. 2025, “the future for water relies on a water conscious society”.

Really well written, Amelia. Thank you for this. I’m afraid growth addiction is rooted too deeply throughout the Colorado River basin for us to see any meaningful action. Every entity is hell-bent to solve this problem without giving up their future growth. Of course, as pointed out, that means middling half-steps, not real solutions.