Introducing the Sustainable Housing Act: Shelter for All in a Steady State

by David Shreve

Housing in the United States (and in many other nations) is plagued by many problems and shortcomings. Among the most critical are increasingly unaffordable prices and bewildering geographic cost variations. Connected to these are additional problems associated with forced sprawl, the needless destruction of vital ecosystems, and labor market rigidity.

Most people would agree with the stance of the Rent is Too Damn High Party, a single-issue political party originating in New York. (Alex Lozupone, Wikimedia Commons)

The residential cost problem is paramount and can no longer be dismissed as a predicament limited to isolated markets. For the year ending in March 2025, U.S. housing prices increased by four percent; significantly more than the 2.4 percent price increases for “all items.” What once distinguished California coastline and Colorado ski towns has now infected all U.S. regions, with ever-fewer outliers.

Historically, U.S. real estate has seldom decreased in price. Until recent decades, however, price increases were usually modest, albeit with booms and busts. In the 21st century, we see a more alarming picture.

In 2023, approximately 27 percent of households with mortgages and 49 percent of renters were “cost burdened,” with housing expenses greater than 30 percent of household income. This is a crisis for which popular “Yes, In My Back Yard” (YIMBY) or “build more” movements do not provide an answer.

Housing should be a source of economic stability and increased quality of life. It should also be environmentally sustainable. Under the status quo, the housing market often diminishes all of this. But the roots of the problems are identifiable, and practical solutions are within our grasp. The Sustainable Housing Act, introduced herein, is designed to encourage and deliver adequate housing with a smaller per capita ecological footprint. It is also intended to arrest some of the misallocation that has made American housing so unaffordable.

The Real Shortage? Smart Population and Economic Policy

Four controllable factors stand out as drivers of the housing crisis: population pressure, the concentration and greed of the building industry, counterproductive macroeconomic policy, and regressive local tax policy. Regrettably, we’ve responded perversely to beneficial fertility decreases. Meanwhile, we’ve ignored the effects of homebuilder oligopoly. Our embrace of “trickle-down” economics and misguided anti-inflation policy has bred extraordinary inequality. And our ignorance of regressive tax structures and their impact—especially at the local level—has made it difficult to right the ship.

Too Many People

Recent world fertility rate declines offer great promise for sustainable prosperity. Indeed, they are a prerequisite. Amid great misapprehension and guided by flawed economic theory, however, many policymakers have responded in panic. We must arrest and reverse this self-defeating and nonsensical reflex.

Continuing population growth has erased all sustainability gains achieved via innovative resource-use efficiencies. However, few in the “developed” world appear to notice. We imagine that innovation will allow us to grow populations without harm—that “more” is beneficial. This allegedly benign growth then forces builders and prospective homeowners onto lands with compromised ecological carrying capacity. Increased daily commutes, environmental degradation, and exposure to natural disasters and insurance crises have all followed. Price relief has not.

An Industry Built for Disparity

Building more does not bring affordability. Indeed, where government has lifted building restrictions, price decreases have been meager or non-existent. “Build more” efforts don’t address many critical factors, including the market dominance of just a few builders. Such oligopolistic, profit-driven markets breed a gross misallocation of housing resources. Under the status quo, few developers and builders seek what housing consumers need: modest, small houses, whether renovated from existing stock or constructed afresh.

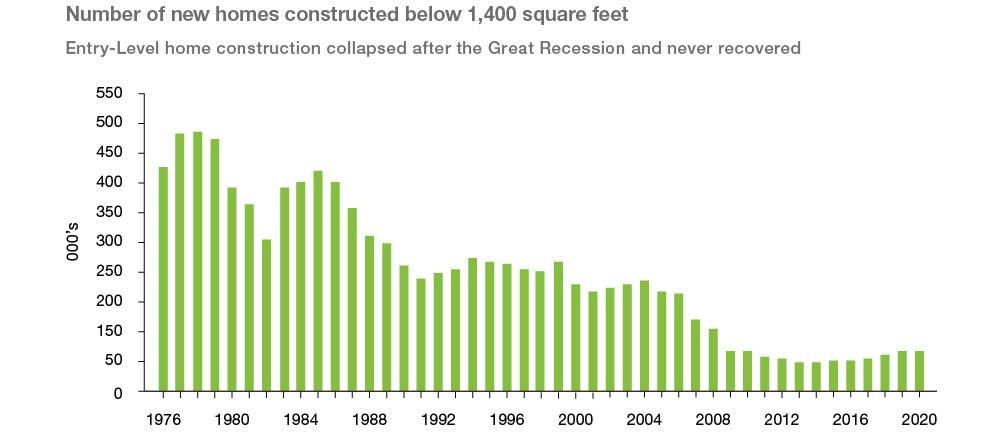

There was a minor exception to this during the run-up to the subprime/mortgage security scandal of 2008. Building smaller happened to match the interests of builders, if only on the margin. Accordingly, construction of new “entry-level single-family” homes (under 1,400 square feet) reached its 21st-century peak in 2004, at 12.1 percent of all newly built single-family homes. Especially since the Great Recession of 2007–08, however, this type of construction hasn’t attracted many builders or investors.

Entry-level home construction has had a downward trajectory since the 1980s. (U.S. Census Bureau)

Even California’s streamlined regulations, reflecting a common goal of builders and YIMBYs, have had little effect on price or supply of the right kind of homes. This is especially true for first-time homebuyers of limited means. Across the country, housing completions overall have either matched or outpaced new household formation over the last thirty years. Yet prices have continued to rise. New-home sales and speculative sales in 2025 are running about 50 percent above long-term averages. Absent another prominent housing bubble in which the poorest Americans and environmental biocapacity are victimized, loosening zoning constraints likely won’t make a difference.

Too Much “Trickle-Down”

Insufficient progressivity in our overall tax structure exacerbates the housing affordability problem. So does restrictive monetary policy. By enlarging (or not addressing) inequality, such policies channel more money into purchases of the most expensive homes, where price sensitivity is the lowest. The result is a misallocation of housing investment. Prices increase at the top, shortages develop at the bottom, and interest rates go up in every tier.

Restrictive monetary policy also depresses investment and employment. In the wake of the destruction, it seduces us with the siren song of growth as the only apparent solution.

Regressive tax policy, in particular, has encouraged privatization and the contracting out of core public services. As a result, hot and cold spots have increasingly colored American economic geography in the 1980s and beyond. Dependent on the geographic choices of private investors and contractors, we share prosperity less widely than before. As a result, regional housing prices are more unbalanced, and workers often can’t afford to relocate for better job opportunities.

Property Taxes: A Unique Local Government Problem

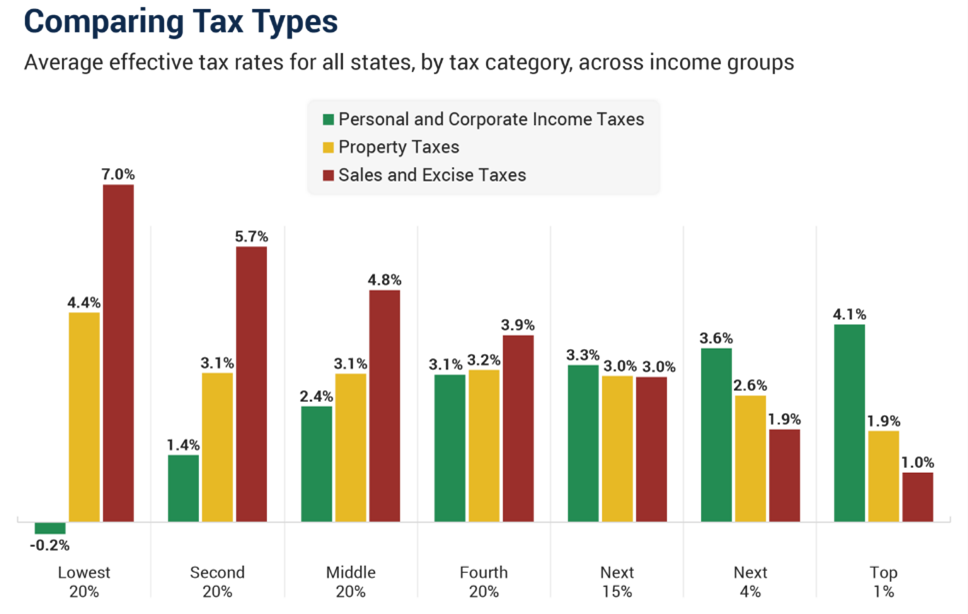

Yellow bars represent property tax rates, which are regressive; higher proportionately at lower incomes. (Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy)

The property tax is the dominant tax vehicle for local government throughout the United States. It adds a squeeze at the bottom of American housing markets, where price sensitivity and misallocation are already the most extreme. Americans have become desensitized to its regressive nature.

With heavy local dependence on the property tax, the poor pay a greater share of their income to local governments than the wealthy, and public service costs outpace revenue growth. These levies on real estate have roiled the nation’s housing markets for decades, serving very few and hindering many. They drive displacement and eviction, widespread tax lien fraud and theft, and artificially divergent property “values.” Property tax reform must constitute one part of a larger affordable and sustainable housing reform.

The Principles of Sustainable Housing

If we acknowledge and address the problems of population pressure, industry concentration, legislated inequality, and regressive local taxation, housing policy reform can make a difference. Good housing policy can transform American shelter in ways that benefit both our protection of natural resources and our bank accounts.

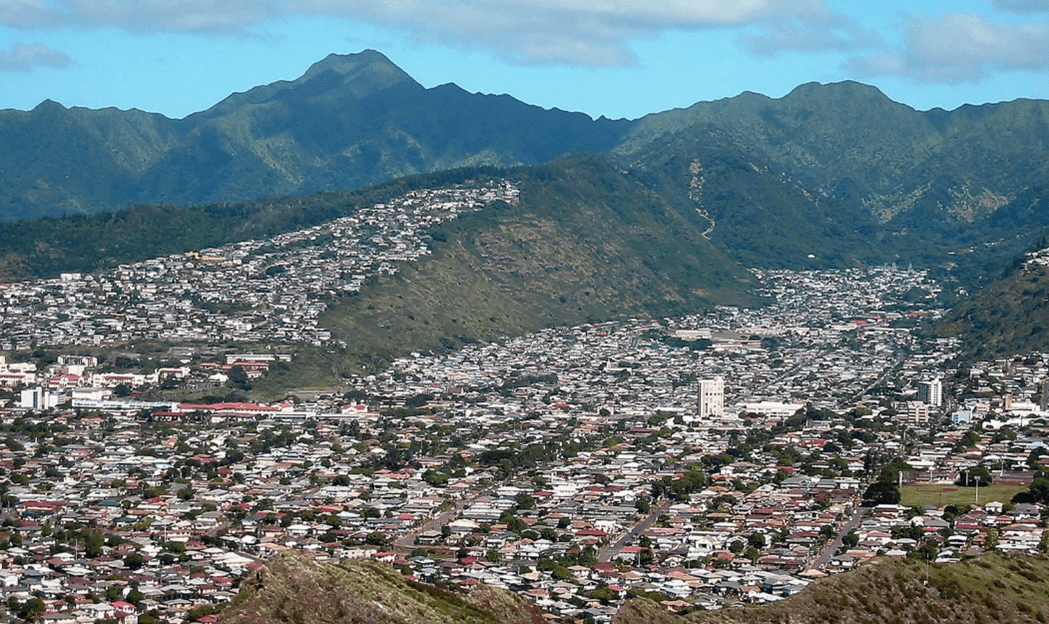

Suburban sprawl, eating the mountain in Honolulu, Hawaii. (Payton Chung, Flickr)

We should return to the average home sizes of the 1970s and 1980s. American households were slightly larger, but houses were smaller, approximately 60 percent of the current average. Energy efficiency has risen dramatically in the last thirty years. Yet, because homes have increased in size and number, they now require more energy overall.

The United States has an adequate supply of homes and apartments in all but a few localities. New housing stock on undeveloped land is seldom necessary. When making zoning recommendations, therefore, policymakers should recognize the futility of simply building more. Renovation should almost always prevail over new construction.

Where new housing is warranted, it should be built with strict standards for economical materials use, efficient energy use, and site placement. Such standards can help avoid the environmental and fiscal costs of suburban sprawl. These include long commutes, natural resource degradation, and expensive infrastructure programs.

Introducing the Sustainable Housing Act

The principles of sustainable housing are applied to the Sustainable Housing Act (SHA), proposed here as a feeder bill of the broader Steady State Economy Act. Sections 1–3 of the SHA establish its short title, Congress’s findings and declarations, and definitions. For example, section 2 includes a declaration that it is the policy of the federal government to encourage the renovation of existing housing stock.

Sections 4 and 5 discourage large residential structures that require excessive electricity or fossil fuel-based energy. New housing-size limitations are proposed as an eligibility condition for any federal government-sponsored mortgage loan, mortgage loan guarantee, or mortgage insurance. These limitations would also apply to Fannie Mae (Federal National Mortgage Association) or Freddie Mac (Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation) secondary-market mortgage loan participation.

Section 6 calls for the formation of two related federal advisory commissions, which the Department of Housing and Urban Development would manage. The commissions are designed to complement existing private associations that have historically developed model building codes and zoning regulations. The Sustainable Housing Building Code Commission would develop and encourage sustainable building techniques and materials use.

The Sustainable Zoning Commission would develop local zoning standards to update and modernize administrative law stemming from the Standard State Zoning Act. It is designed to improve and develop zoning regulations that prevent overbuilding, sprawl, and unsustainable residential building sizes and site development practices.

In the United States, states and localities hold “police power” over land use. Recognizing this, the new commissions would work with the Commission on Economic Sustainability to create strict and sensible land-use regulations for universal and uniform adoption. Existing private associations, formed at the behest of the Coolidge administration Department of Commerce, already encourage universal and uniform standards. The newly proposed commissions would emphasize sustainability.

Sections 7–13 of the SHA establish two new excise taxes. One is a two-tier federal luxury excise tax based on the size of any new home construction. It encourages a return to the building or renovation of smaller homes.

American McMansion: Why, oh, why? (Elana Centor, Flickr)

A five percent excise tax is proposed for the first tier, for new homes with conditioned living space between 2,000 and 3,000 square feet. A ten percent tax is proposed for new homes with conditioned living space over 3,000 square feet. There is one special renewable energy exemption for structures that fall into the first tier, and for which self-generated renewable energy supplies a minimum of 75 percent of expected energy usage.

The second proposed excise tax is designed to discourage sprawl and the environmentally costly public service delivery and commuter travel it generates. A tax of ten percent of the recorded sales price would be imposed for any new structure that requires the extension of public water and/or sewage lines and connections beyond a specified minimum.

Section 14 prohibits newly constructed single-family homes that exceed 5,000 square feet of conditioned space, with two exemptions for renewable-energy applications. This section is intended to curtail the long-running trend toward larger homes. However, cost factors have recently arrested that trend, so the house size that the SHA prohibits constitutes only a small percentage of the home construction market. The bill is designed to reduce the construction of unsustainably large homes even more sharply.

Collectively, the policies proposed in the SHA promise to make housing more compatible with a prosperous steady state economy. They provide a launchpad for Americans to address the ongoing housing cost crisis. There is no better time than the present to explore opportune pathways to more affordable and sustainable housing.

David Shreve is a Senior Economist at CASSE.

David Shreve is a Senior Economist at CASSE.

Apologies for only now having had time to read this, very interesting, and very timely. I hope we see something like the SHA implemented somewhere, it’s badly needed.

I was curious, in the article 2004 or so was mentioned as a time when builders had a bit more incentive to build smaller dwellings (which we desperately need). Is it possible to say what factor or factors were incentives to build a bit more reasonably sized dwellings in the 2004 timeframe? I wasn’t quite sure from the article, me culpa if I missed it.

Cole,

Indeed, the original–slightly longer version of this article–included a bit more on this. Essentially, what “bent the curve” in a marginal way during the early oughts was the desire to draw in potential homebuyers of limited means and/or deficient credit scores. Naturally, if the whole Ponzi scheme of the “Big Short” housing bubble was predicated on passing off the risks associated with such construction and its associated finance, then the construction had to at least resemble something these prospective homeowners might conceivably afford, hence, the slight reversal then of a much longer running trend toward bigger and bigger homes. And we also weren’t that far from the W. Bush recession, which may have dampened the appetite somewhat for bigger homes among middle-class buyers.

Housing prices vary a lot depending on whether the local economy attracts more people to employment. The same house will sell for 2 million in a tech hotspot but only 20,000 in a rust belt declining town. Growth is the problem, not the solution.

My all too brief rendering here of the “hot-cold” economic geography of the United States, which emerged in a marked and somewhat unprecedented way in the Reagan years, was a comment on this phenomenon, related to growth, as you note, but also to overall inequality and newly ascendant geographic inequality. A “growth-first” mentality doesn’t guarantee such an outcome, but it certainly makes it more likely. This is especially so in the more recent and shockingly still dominant political economy whereby counterproductive tax cuts for the well-to-do have been combined with perverse “anti-Keynesian” Keynesianism.

Some problems here. !: “Sustainable” is usually a code referring only to energy efficiency and use of renewable energy sources. Great, but we also need to build buildings which will survive, with little damage, all the natural hazards of the site. See FEMA P-320 for wind hazards.

2: A big problem with smaller homes is no space, no rooms, for people to do physically productive work = making things. Home sewing, wood shop; all work at home (for self or business) needing more space and privacy than a computer workstation. From 1950s, junior does homework on kitchen table. Housewife uses dining room table to lay out patterns & cut fabric – getting back strain because table is too low. Sewing machine stuffed against a wall w/o outrun surface. “Bedroom suburbs” have “bedroom homes” because hubby works in office, housewife does no work. Before you shoehorn everyone into these brainless dwellings, find out what people need to be able to do at home, in dedicated spaces.