Investors Profit from the Affordable Housing Crisis

by Amelia Jaycen

Today, we see endless suburban sprawl and no shortage of stories about the U.S. affordable-housing crisis. So, why aren’t there enough homes yet?

New homes in Greenville, North Carolina. (City of Greenville, PDM 1.0)

The story is one of “artificial scarcity,” in which there are plenty of means to close the affordable-housing gap, but scarcity is created by investment companies buying up homes. Investors own 20 percent of single-family homes in the United States. Loopholes in the U.S. tax system allow them to skip paying taxes. Real estate is a safe bet, and investors structure their companies to fall outside the regulatory scope of investment laws.

Everyone needs a home, so home buyers are a captive customer base. Without regulations in place to deter bad actors, real estate is a lucrative investment for those who know how to take advantage of the system.

In February, U.S. Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR) and U.S. Representative Adam Smith (D-WA-09) introduced the Humans Over Private Equity (HOPE) for Homeownership Act to impose new taxes on hedge funds that own homes. The bill, currently with the Senate Finance Committee, is co-sponsored by U.S. Senators Ruben Gallego (D-AZ), Mark Kelly (D-AZ), Angus King (I-ME), Chris Van Hollen (D-MD), and Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and U.S. Representative Linda Sánchez (D-CA-38).

The bill’s supporters say large institutional investors and hedge funds are taking over the U.S. housing market at an alarming rate, to the detriment of working families.

“Houses should be homes for families, not profit centers for hedge funds,” Senator Merkley said in a press release accompanying the bill’s introduction. “The HOPE for Homeownership Act fights back against billionaire corporations controlling the single-family housing market. Let’s kick hedge funds to the curb to restore the dream of homeownership, one of the foundations that working families need to thrive.”

Subsidizing Wall Street

Wealthy businesses and individuals have plenty of options for turning investment capital into increased wealth. Lower classes, on the other hand, have less capital and fewer options. The main pathway for lower-class families to increase wealth is through the investment of home ownership. The corporate-landlord phenomenon allows investors to manipulate the housing market for profit—a growing and dangerous trend that is locking families out of the home ownership market.

For the wealthy, investment options include the stock market, bonds, mutual funds, money market funds, various types of private-equity investments, and hedge funds.

The stock market is high-risk. Bonds are slow. Money market funds and mutual funds are open to the general public, have low minimums, and are regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

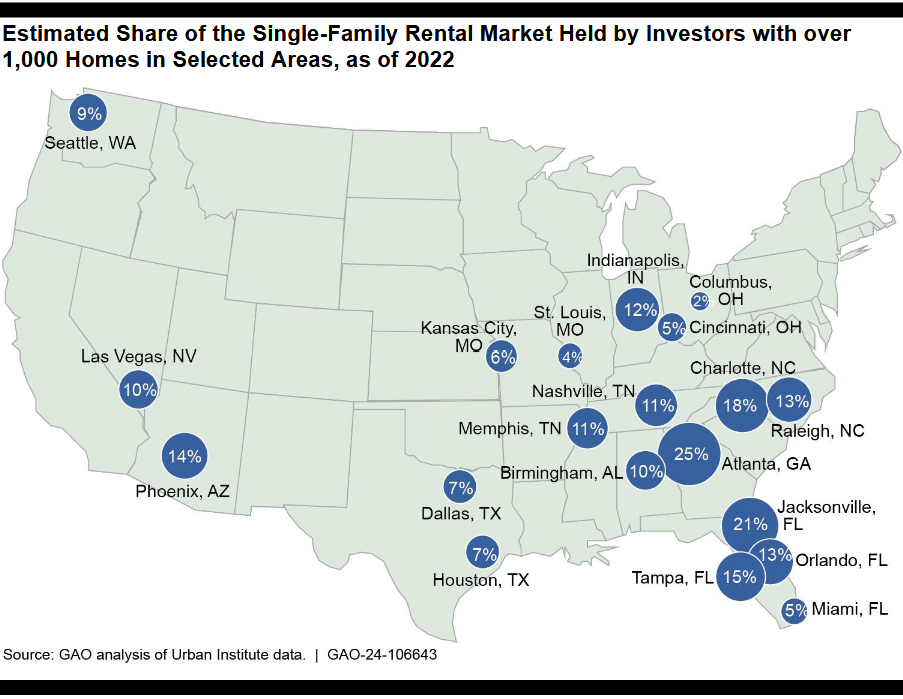

Estimated share of the single-family rental market held by investors with over 1,000 homes in selected areas, as of 2022. (GAO, Public Domain)

Private-equity funds and hedge funds, on the other hand, are only open to private investors, usually involve larger investments, and are less regulated by the SEC. The Investment Company Act of 1940 exempts private equity and hedge funds from SEC registration and public disclosure. It also exempts companies that invest in real estate.

In hedge funds, groups of investors pool their money and allow the fund to be actively managed by professional fund managers. Active management means using aggressive, novel strategies to achieve higher returns than conventional investment funds. Hedge fund managers use calculated strategies to hedge their bets. Because of the focus on fast returns, hedge fund managers are more zealous and prone to use unconventional strategies. That makes hedge funds the most predatory corporate actors in the housing market.

Private-equity firms have longer timelines for investment than hedge funds. Private-equity investors are usually more involved in the firm’s operations, because the capital invested in private equity is locked in for the lifetime of the fund. They often focus on buying private companies to increase their value, but, in the decades since the 2007 housing market crash, they have become increasingly invested in the housing market.

Real estate investment trusts (REITs) are companies that own real estate and allow people to invest in real estate without being property owners. REITs can be publicly traded on the stock exchange, or they can be in the form of private funds or mutual funds.

Wall Street Buying Main Street

The history of investment firms’ involvement in real estate and single-family home ownership dates back at least as far as the Savings & Loan Crisis of the late 1980s. When Savings & Loan banks failed, the U.S. government bailed them out. Then, the government needed to unload a large amount of real estate back into the private sector. Seizing the opportunity, financial firms bought large bundles of real estate investments from the government. After seeing how much profit could be made through housing investments, private equity stuck around—buying distressed properties low and selling high in cornered markets.

International Housing Finance Policy Roundtable focusing on the subprime mortgage crisis, at HUD Headquarters. (National Archives at College Park, Public Domain)

The U.S. housing market crash of 2007 and the COVID pandemic provided two additional points at which large private-equity firms capitalized and bought up more properties in trouble. After the 2007–2009 financial crisis, institutional investors emerged in full force and purchased large numbers of foreclosed homes.

The trend of corporate real estate purchasing has continued to create the broken system we see today, in which there are more private-equity funds than McDonalds. Many of them are gaming the housing market. Alongside hedge funds aggressively working for fast returns, private-equity firms’ buy-to-rent strategy is a stark example of “Wall Street buying Main Street.”

The financial structures of the firms and the investment strategies they use are broad and complicated, making it difficult to determine the best way to tackle the problems they introduce in the market. But it is clear that numbers of mega investors have jumped sharply since 2000. Progress Residential quickly became one of the largest, and Blackstone is the most dominating force among them, even buying up properties in markets outside the United States, including 4,500 homes in the UK. Other big-time players include American Homes 4 Rent, Colony Capital, Starwood, Capital, and Waypoint Real Estate Group.

Houses No One Can Afford

Because there are so many corporate homeowners, there are fewer houses on the market available for families and first-time homeowners to buy. Fewer homes on the market creates an artificial scarcity, exacerbating already bloating growth patterns to create a narrative that screams “build baby build.” By turning the narrative away from “affordable,” focusing instead on “shortage,” investment firms position themselves as essential in solving the shortage by supplying more and more homes to meet the demand.

In 2021, corporations bought 28 percent of all the homes sold in Texas, 19 percent of homes sold in Georgia, and 16 percent of homes sold in Florida. Lawmakers supporting bills like the HOPE Act insist thousands of houses should be released from the hands of investors and put back on the market to address the shortage of homes available to buy.

Mobile homes are one of the last remaining affordable housing options in America. Now they’ve become private equity’s latest target. (More Perfect Union)

Meanwhile, the real shortage is affordability in housing as well as health care, food costs, childcare, and utility bills. Housing prices continue to rise, and wages are not keeping up for people riding the poverty line, as well as high-income earners. The Texas comptroller reported its key findings on the deterioration in housing affordability to address 9 out of 10 Texans saying housing is not affordable. A number of studies examining the relationship between home and rent prices and corporate owners found ownership concentration among corporations does raise prices.

The National Low Income Housing Coalition says the United States is short 6.8 million affordable housing units. But this an indicator of gross imbalance, not a true market-wide shortage. The coalition notes affordability is the real issue, because housing is, for many, the thin line between personal security and homelessness. Private equity is also buying up mobile home communities, attacking the most vulnerable homeowners in an alarming, predatory, amoral trend.

Large investment firms continue to buy up housing and grow more bold, gaming the system as if playing the stock market, pricing everyday families out of the option to buy homes. The lack of moral responsibility led Senator Merkley and Representative Smith to ask the question: What are hedge funds doing in our housing system, and how can we get them out of it?

HOPE for an End to Gaming the System

Investors own 20 percent of the 86 million single-family homes in the United States, but they don’t pay taxes like every other homeowner. The Internal Revenue Code of 1986 contains “safe harbor” provisions that allow hedge funds, which have complex structures, to avoid certain taxes or penalties. Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Section 1031 allows corporations to defer paying taxes on properties if they sell the property to another investor, allowing a perpetual loop that keeps homes off the market and lines the pockets of wealthy corporate landlords.

Legislation to end hedge funds in the housing market notes “eligible buyers” should be families only, not corporations. (respres, CC BY 2.0)

President Joe Biden proposed putting a cap on the Section 1031 loophole, but the proposal got no traction. Legislation introduced by Merkley and Smith in 2023, the End Hedge Fund Control of American Homes Act, sought to force hedge funds out of the business. It noted “eligible buyers” should be families only. It mapped a pathway for hedge funds to exit the housing market in an orderly fashion: by paying $20,000 tax on every home they own over 100 homes and selling at least 10 percent of the single-family homes they own each year.

The 2025 version, the HOPE Act introduced by Smith and Merkley in February, establishes a tax penalty of 15 percent for hedge funds that buy single-family homes. It ends depreciation and mortgage-interest tax breaks. The bill requires hedge funds to sell 10 percent of their currently owned single-family homes every year for 10 years or face a $5,000-per-home penalty. It also prevents them from selling the homes to other funds. The bill’s supporters hope to break the cycle of continued corporate gambling with U.S. single-family homes.

“Hedge funds are buying up larger and larger shares of single-family homes—hoarding the housing supply to turn huge profits for their rich investors and crowding out hardworking families from the market,” Senator Chris Van Hollen said in a statement for the Steady State Herald. “This legislation ends the warped incentives that are enabling deep-pocketed hedge funds and private equity firms to dominate the housing market, while leveling the playing field so more everyday Americans can achieve their goal of homeownership and build wealth.”

Corporations are Destroying Human Habitats

The problem with private equity and hedge funds in the U.S. housing market is more than a savvy investment trend. It is a coordinated attack on working-class people by price-fixing cartels engaging in unlawful conspiracies that “unreasonably restrain trade or commerce” and fraudulently take money from low-income citizens.

When gainfully employed couples can’t find an affordable home, the economy is broken. (BC NDP | CC BY 2.0)

The moral crisis continues to deepen, with corporate landlords becoming even more merciless, as with the trend of using algorithms to coordinate rent hikes. The hawkish strategies used by corporate landlords to cheat renters and home buyers may be only the “tip of the iceberg.”

Beverly Hills City Councilman John Mirisch has been an outspoken leader on anti-speculation housing policies throughout his time in public office. To paraphrase his logic: Homes are designed to live in. Housing is a human right, not an investment tool, so the kind of profiteering represented by the corporate landlord is “not only bad policy, it’s also immoral.”

Corporate landlords are a symptom of the “urban growth machine.” Their attempts to be seen as heroes in the housing crisis grow thin as they demonstrate an increasingly disturbing lack of decency, as Mirisch has pointed out.

“Corporations are largely responsible for [California’s] jobs and housing imbalances,” he wrote. “Corporations, led by Big Tech, are also largely responsible for increasing income inequality, which is perhaps the single most important cause of the housing affordability crisis in the state, not to mention a raft of other social problems.”

Affordability Is a Steady State Economy

The steady-state solution for the crisis is a sustainable housing policy that deconstructs the current housing industry built for disparity. As CASSE’s Senior Economist Dave Shreve reports, “oligopolistic, profit-driven markets breed a gross misallocation of housing resources.”

While CASSE’s Sustainable Housing Act wasn’t specifically designed to address corporate landlords, it addresses the root of the problem of affordable housing. It digs deep into fundamental issues across U.S. economic, monetary, and tax policy.

The 2007 housing crisis no one saw coming. Will we make the same mistake with hedge funds taking over the housing market? (Occupy Irvine | CC BY 2.0)

The author notes the need for property tax reform at the local level, which is currently fraught with regressive tax policies that “add a squeeze at the bottom of American housing markets.” Addressing an outdated, dysfunctional local property tax system is one piece of low-hanging fruit to put more money in the pockets of first-time home buyers. Zoning regulations that look beyond the “build more” narrative to limit sprawl and keep local costs low, are another.

The Sustainable Housing Act also proposes an excise tax to address the fundamental sources of scarcity. It suggests taxing sprawl to limit unnecessary gray infrastructure, reduce public service costs, and encourage sustainable zoning, economical materials use, and efficient energy use.

“Most real estate appreciation, translated into the outsized returns of corporate investors, is built on taxpayers’ public investments like infrastructure and public services,” Shreve said. “In return for their investments, taxpayers get to pay higher rents and increasingly unsustainable mortgages.”

“There is a role for both positive and negative reform here,” he said. “Positive, to introduce new tax policy, for example, that imposes relatively higher rates on capital gains associated with hedge fund, private equity, house-flipping consortia investment schemes. And negative, to roll back subsidies given to such investors under the false pretense that if they only increase their investment, supply will expand, and prices will stabilize or drop.”

Amelia Jaycen is a program manager at CASSE.

Amelia Jaycen is a program manager at CASSE.

"Rappahannock County Courthouse" by taberandrew is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

"Rappahannock County Courthouse" by taberandrew is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

please help me get this word out to mass. where conservation and housing

advocates are at loggerheads.

Un-American terminology impairs a correct understanding of parts of the problem.

The USA has no royalty. The only “classes” in the USA are those in educational institutions, and those ad hoc classes for short-term education. It’s un-American to talk about “classes” of people outside these educational contexts. And using “class” as a proxy for household income is also un-American. We are not our current incomes. And as for the term “working families,” unless you’re the Flying Wallendas, the Jackson 5, or the Von Trapps, you work as an individual, not a family. If you use “working” as a code for a certain range of low income, that’s an un-American “class” label. “Working” means employed by others, or self-employed. The highest-paid CEO in his corner office is among the “working people” of this country.

I also didn’t see even a mention of the need to get the Federal Minimum Wage caught up to where it should be, given inflation since the last time it was caught up to provide an adequate income, which was decades ago.

Great to see this detailed analysis of the harmful impacts of increasing corporate ownership of the private housing stock. This is an important component of housing unaffordability.

Another important component of the problem is immigration-driven population growth. For a discussion of this component, see https://overpopulation-project.com/housing-costs-a-matter-of-supply-and-demand/

I note that this essay references a steady-state economy as fundamental to addressing overall affordability. An essential component of such an economy is ending population growth.

Well, in honesty, capitalism and its advocates should be evaluated by forensic psychiatry at this point. To see if it’s just insanely criminal, or rather criminally insane. What else?

Thanks, Amelia Jaycen, for this thorough evaluation of the corporate components of housing

at a shortage. And more subtly, the essay shows the public relations marvel in their work with builders looking like the solution to the shortage while their focus on the high end of the housing market, and while corporate control of that market as sets of aggregate commodities, add to the shortages. The HOPE for Homeownership Act and CASSE’s Sustainable Housing Act take steps toward remedies. Keep HOPE alive for more support of these chapters of the call to limit ongoing economic growth—in the face of current cultural assumptions, this call for taming can seem a call of the wild because tapping thinking and practices outside the mainstream.

The commentators offer more suggestions to reduce the housing problems including alan French hoping to balance conservation and housing needs, Jean SmilingCoyote calling for hiking of the minimum wage, finding ways to control the (human) population as Philip Cafaro suggests, and getting more people to notice the criminal insanity of capitalists, as koenraad priels boldly suggests. Back to the essay. These suggestions would all be addressed, or at least their problems mitigated, by encouraging more people to notice the ill effects of “perpetual growth” distracting from or hemming them in, amplifying housing shortages, and encouraging market speculation. I end with those words, “perpetual growth,” the first words of the essay.

Big investors driving housing market inflation is a real zinger! We’ve got to have an earth centered value system to see this change. I’d like to read a piece on wasted high-rise office space. Another area of investor driven misused resources.

Good point, Samantha Timely. Another example of the inefficiencies of market-oriented efficiencies.