“Landman”: Hollywood Meets the Growth Dilemma

by Owen Cortner

The Permian Basin, shown in red, accounts for 46 percent of U.S. oil production (Emmanuel Roquette, Wikimedia Commons).

The new TV series, Landman, offers a window into the rugged world of the oil industry in West Texas. Billy Bob Thornton plays Tommy Norris, a “fixer” for an oil company, who roams the high-stakes territory of “The Patch,” a.k.a. the Permian Basin. Norris navigates shady deals and dangerous gambles, most of them highly cinematic (if occasionally thinly written). Packed with tension and drama, this depiction of a modern-day Wild West also provides an opportunity to contemplate the oil industry’s staggering scale and its role in perpetuating the myth of infinite economic growth.

Landman is the creation of Taylor Sheridan, one of the biggest writers in the business, who also developed Yellowstone and 1883. The fictional drama captures the grit and intensity of the oil industry. However, some elements are pure Hollywood. Workers use tools that throw off sparks near flammable materials, and cartels land planes on rural roads to unload drugs (though a co-creator says that’s based on true events). Yet, beneath the dramatization lies an undeniable truth: The oil and gas industry is vast, powerful, and deeply entrenched in the global economy.

A Colossal Industry Close to (My) Home

“The more they grow, the more we grow,” says Thornton’s character; “they” being the few sectors of the global economy bigger than oil. This one line sums up the relationship between oil and, well, pretty much everything else. Consider these facts about the oil and gas industry:

- With over $4.2 trillion in annual revenue, it ranks as the 5th largest industry globally.

- It profits to the tune of $3 billion daily.

- Even larger industries, such as transportation and chemicals, depend heavily on oil and gas.

- Oil and gas are the core of modern industrial agriculture.

- They are in everything from clothes to cosmetics, not just in the tanks of our cars.

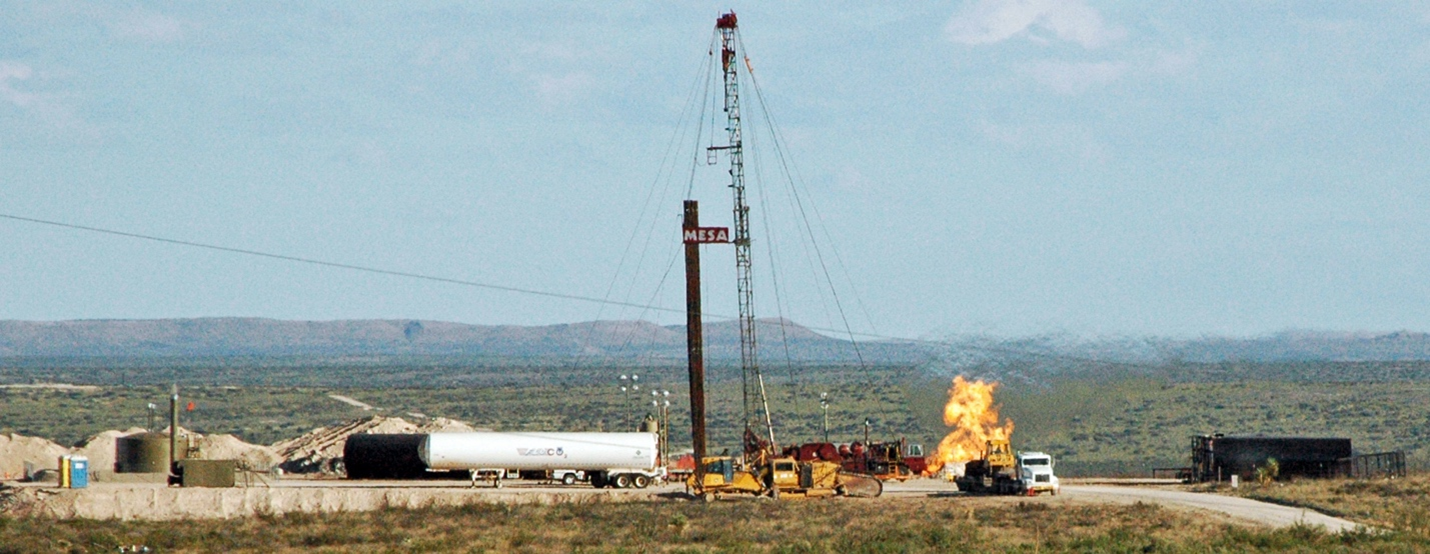

Natural gas flare at active drilling site near Carlsbad, New Mexico, in 2007 (James St. John, Flickr).

For those living in oil-producing regions, like my home state of New Mexico, Landman hits close to home. In 2023, two counties in New Mexico accounted for 17% of onshore oil production in the contiguous United States. This is a staggering figure for a state with a small population and economy.

I am both proud of and troubled by this. It feels good to say that my state is small but mighty—it is important on the world stage for producing such a useful commodity. On the other hand, that commodity is contributing to climate change.

Climate change can seem like a luxury concern when changes in the price of oil can decimate education, health, infrastructure, and other industries. It’s not as if New Mexico isn’t subject to climate risks. Droughts have played a major role in the decline of civilizations in this region. The locals who don’t prioritize climate mitigation aren’t ignorant, they are just dealing with more immediate problems.

Lea County in the southeastern part of the state was the first U.S. county to produce more than 1 million barrels of oil per day. Oil and gas tax revenue and royalties fund anywhere between a quarter and 40 percent of New Mexico’s state budget. Yet despite full state government coffers in 2023 and 2024, almost 18 percent of the population lives in poverty. Oil and gas often enrich industrial “cores”, leaving “peripheral” producing communities exploited.

Clean or Just an Alternative?

Wind turbine and oil pumpjacks in Austria, 2008 (Wikimedia Commons).

A scene in Landman offers a powerful critique of the low-carbon energy industry. Norris’s daughter, observing windmills dotting the oilfield landscape, asks, “You use clean energy to power the oil wells?” He responds, “It’s alternative energy, and there’s nothing clean about it.”

This exchange encapsulates a troubling reality: Low-carbon energy is increasingly used to power fossil fuel extraction. What’s more, wind turbines, solar panels, and other “green” technologies rely on intensive resource extraction and manufacturing processes made possible by fossil fuels. If these systems serve to prolong the fossil-fuel economy, can we truly call them clean?

Bridging Culture and Degrowth

Landman’s focus, the oil industry, is a microcosm of the broader growth economy. Fossil fuels drive the expansion of countless industries, which then demand more energy, creating a feedback loop of resource extraction and consumption. The characters in Landman view growth as desirable—if not inevitable—but this perspective ignores the limits of our planet.

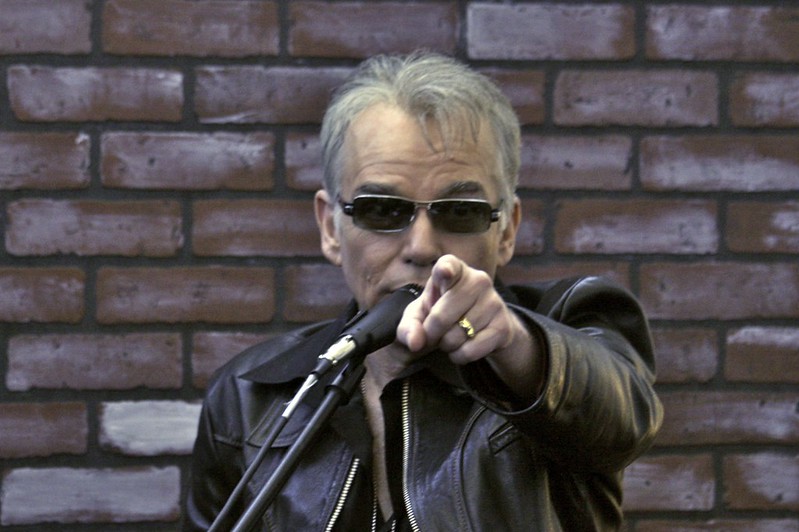

Come for Billy Bob Thornton, stay for reflections on the sustainability of our economic systems (Ed Schipul, Flickr).

Perpetual growth is not only physically impossible but also morally questionable. The environmental and social costs of fossil-fuel extraction and consumption, from pollution to resource inequity, are mounting. Yet mainstream economic thought continues to promote growth as the ultimate goal, failing to address its inherent contradictions.

Landman highlights these contradictions within the oil economy. By engaging with stories like this, we can bring the principles of steady-state economics into public discourse. Academic theories like the trophic theory of money gain resonance when contextualized within cultural narratives, connecting economic concepts with everyday experiences.

What Changes Are Possible?

“We don’t do this ‘cause we like it. We do this ‘cause we run outta options.”

Phasing out fossil fuels will require systemic change (JYB Devot, Wikimedia Commons).

With this line, Landman—perhaps inadvertently—hits at the crux of the problem. The oil industry’s scale is just as staggering as the show depicts. This should prompt critical reflection, not blind acceptance. If we need planet-heating fossil fuels to support our growing population and consumption, shouldn’t we consider changing the status quo?

The time has come to challenge the growth paradigm that fuels industries like oil and gas. We should advocate instead a steady state economy; one that prioritizes ecological balance, social justice, and long-term well-being over endless expansion.

The problem isn’t just the oil industry—it’s a systemic failure to prioritize ethics in economic decision-making. Leading universities churn out graduates skilled in maximizing profits but unprepared to grapple with the moral implications of their work. Without a grounding in ethics, decision-makers perpetuate systems that prioritize short-term gains over long-term sustainability.

Landman may dramatize the oilfields, but the questions evoked about growth and sustainability are plenty real.

Owen Cortner is an independent researcher.

Owen Cortner is an independent researcher.

Hi CASSE people,

I recently saw ‘Honeyland’, a striking documentary filmed in Macedonia, that graphically and poignantly raises issues of both overpopulation within a family, and resource scarcity. It has English subtitles, but the issues become apparent not by being talked about, but through the story’s situation. I really liked it.

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt8991268/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Honeyland

Brian

–