Remembering Peter Seidel: Philanthropist, Futurist, and Good Soul

by Brian Czech

Peter Seidel will be sorely missed. (Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons)

On July 20, at the age of 98, a giant in steady-state philanthropy left the world he worked so hard to help. Frederick George Peter Seidel (1928–2025) played a huge part for small organizations like the Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy (CASSE). Peter was CASSE’s best friend, biggest benefactor, and broadest champion. His contributions ranged from academic and editorial to strategic and financial.

Without Peter, CASSE as we know it would not have existed. More than anyone, he lifted CASSE from the financial scree of struggling non-profits to a respected place in the landscape of sustainability think tanks.

On a personal note, I found something priceless in Peter: the encouraging support of a warm soul who provided unwavering moral support, camaraderie, and conviviality. When my own father—another Wisconsin man from the “greatest generation”—passed away, Peter became my go-to confidant for strength and encouragement.

Crossing Paths with a Kindred Thinker

As I recall, I first encountered Peter in 2003, at a U.S. Society for Ecological Economics conference in Saratoga Springs, New York. Our paths would cross regularly in that first decade of the 21st century. Not only did we find ourselves at the same conferences, but in the same sessions and in the same conversations—and invariably on the same side, in the event of controversy or debate.

Album-quality photos were never prioritized by Peter Seidel. This snip from an appearance on a Cincinnati public television show is approximately from Seidel’s 90th year on Earth.

And controversy was never far away. We both recognized the fundamental conflict between economic growth and environmental protection. We both were incredulous to find so much “green growth” talk, even among environmental professionals and journalists. We both were determined to raise awareness of limits to growth, and to put an end to the win-win rhetoric that “there is no conflict between growing the economy and protecting the environment.”

By the time I met him, Seidel was already an elder statesman of limits to growth. He had been spotting the red flags for decades before I came along with my specialty on the conflict between economic growth and biodiversity conservation. Seidel had seen it all: DDT, a burning Cuyahoga River, Love Canal, the destruction of the ozone layer, coral bleaching, endangered species, resource shortages, and wars too numerous to speak of. Biodiversity loss and climate change were just two more insults—albeit huge ones—heaped upon a planet subjected to rabid GDP growth.

Academics, Adventure, and Architecture

Seidel and I hit it off with stories of work life and academic pursuits that, for each of us, started in our home state of Wisconsin. Venturing forth from his Milwaukee childhood, Seidel became a farmhand, factory worker, salmon fisherman in Alaska (in the days of log-trap fishing!), carpenter, professor, architect, urban planner, and author, roughly in that order. In the midst of the earlier tasks, after a year of college in Madison at the University of Wisconsin, he obtained a B.S. in Architectural Engineering from the University of Colorado.

The Wisconsin River: one of the many natural wonders that instilled a love of the Earth in Peter Seidel. (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, Peter Gorman)

Why Colorado, and not Wisconsin? Because Peter loved the outdoors, and the adventures that came with it. He loved his beautiful Wisconsin, for sure, and canoed the entire length of the Wisconsin River, from the headwaters on the Michigan border to its mouth along the mighty Mississippi. But, as with a lot of young, vigorous adventurers, he just had to get to the mountains, too. And he was a skier, so Colorado especially beckoned to him.

Mind you, I am going off memories of many conversations, scattered through the years, along with a handful of notes. Any chronological errors are on me. But somewhere in this mix of learning from and reveling in Planet Earth, Seidel performed a tour of duty in the Navy, right on the heels of World War II. The Navy capitalized on his keen mind for the development of sonar and radar technology, which sparked a broader interest in engineering.

Eventually returning to the Midwest for a Masters in Architectural Planning from the Illinois Institute of Technology, Seidel studied under renowned architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. In those days, Ph.D. degrees were much rarer, and not so necessary for a professorial life. Soon, Seidel was on the faculty of the University of Michigan, then Virginia Tech. He also taught at the Central China Institute of Science and Technology.

A Philanthropic Soul

I often wondered how the descendent of German immigrants with a farming and factory background found the money to support CASSE along with the Worldwatch Institute, Global Footprint Network, Union of Concerned Scientists, and social wellbeing campaigns too numerous to list. As I got to know him, eventually the story came out. Seidel’s sonar/radar stint in the Navy put the earliest computer technology on his radar. Decidedly not a materialistic spender, his modest savings gravitated toward the earliest stocks of IBM, General Electric, and eventually Microsoft. The rest is financial and philanthropic history.

Of course, it takes more than money to become a philanthropist. It takes heart and soul, passion and commitment. Seidel had all those characteristics in spades.

Among the many causes he took a supportive interest in—architecture, literature, urban planning to name a few—eventually his greatest passion became limits to growth. He attributed an awakening to futuristic concerns to The Crazy Ape by the wide-ranging Hungarian scholar Albert Szent-Györgyi. Crazy Ape planted in Peter, circa 1950s, a skepticism of human discernment that preoccupied his thinking for decades to come.

Author of The Crazy Ape, Nobel-Prize-winning Albert Szent-Györgyi shared Peter Seidel’s concern that humanity is too preoccupied with technological progress. (Public Domain, Danmarks Nationalleksikon)

Seidel became active in the World Future Society (WFS), which started in 1966. This was somewhat of a heyday for limits to growth literature. Silent Spring and Small is Beautiful came out in the early 60s, and WFS members would cut their futuristic teeth on books such as The Population Bomb (1968) and The Limits to Growth (1972), too.

By the time Herman Daly’s Steady-State Economics was published in 1977, Seidel was fully prepared to load up his conceptual toolkit with ecological macroeconomics. When the International Society for Ecological Economics was established in 1989, Seidel took an active interest, particularly in the prospects for raising awareness of limits to growth. He was not enamored, though, with the emphasis on microeconomics (such as estimating values of natural capital and ecosystem services), and favored a full-fledged focus on the limits to population and economic growth.

When CASSE was established in 2003, with its crystal-clear position on economic growth, Seidel quickly found it to be a favorite cause. He was one of the first 50 signatories of the CASSE position, along with the likes of Herman Daly, Bill Rees, and Richard Heinberg. A long-running relationship commenced.

Surrounded by Beauty

While I got well-acquainted with Peter’s professional, philosophical, and philanthropic interests, Peter was never one to boast of his personal life. Yet anyone who ever stayed with Peter at his Hamilton Avenue apartment, overlooking the famous Northside District, discovered his refined aesthetic tastes. Up on the 15th floor, this early-rising gentleman would watch the morning light casting about the Northside District and the Buttercup Valley Preserve.

Woven among walls and tables of books, Peter had an art collection that was proportional and tasteful. One couldn’t miss it, but it didn’t steal the show, either. Not from the books, and certainly not from the life-sized photo-canvas of his beautiful, beloved wife, Angela. She was an opera singer who left the world far too early (1983) for Peter’s sake. But she also left him with musical memories that he built upon with a collection of classical and operatic scores.

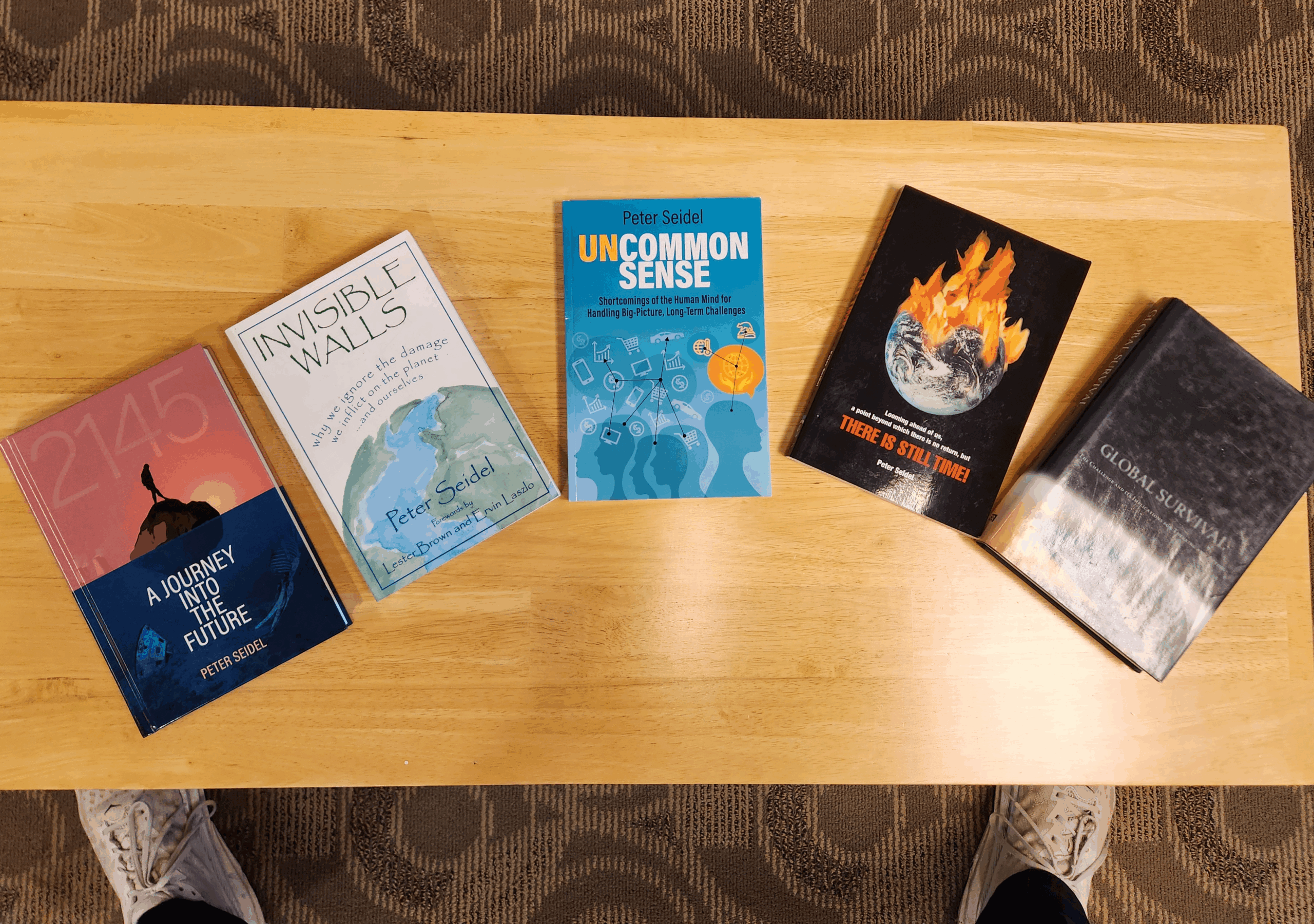

Peter Seidel left an impactful body of work behind.

Eventually, Peter used his aesthetically pleasing, inspiring surroundings to write a number of books, starting with the highly unique Invisible Walls. The mental, psychological “walls” he contemplated made it extremely challenging for Homo sapiens to deal with environmental, social, and political crises. CASSE was fortunate to publish (with our Steady State Press imprint) Peter’s culminating thoughts on these matters with Uncommon Sense: Shortcomings of the Human Mind for Handling Big-Picture, Long-Term Challenges.

Peter took on the challenge of futuristic fiction with 2045; a year that feels less futuristic by the day! Nine decades into life, Peter followed up with 2145: A Journey Into the Future (also with the Steady State Press).

While we journey into the uncertain future—we humans with our limited capacity to do right by the spectacular Earth we inherited—we can take heart from the fact that well-lived lives are not unprecedented. There’s a lot of hope in that, and it’s a good way to pay homage to Peter Seidel.

Brian Czech is Executive Director of CASSE.

Brian Czech is Executive Director of CASSE.

Wonderful tribute. Thank you for writing Brian.

I knew Peter through Community Friends Meeting and an environmental group named Imago in Cincinnati. Thank you for weaving so much into this portrait of Peter – he was ahead of his time as the limits to growth are defining our future, if only we would wake up. Thank you for carrying the message forward.

I knew Peter through Community Friends Meeting and an environmental group named Imago in Cincinnati. Thank you for weaving so much into this portrait of Peter – he was ahead of his time about the limits to growth, if only we would wake up. Thank you for carrying the message forward.

Though saddened to hear of Peter’s passing, I enjoyed reading your tribute to him, Brian. I remember first contacting him after I saw that he was featured in an annual report of the Global Footprint Network. This would’ve been fairly soon after I joined CASSE in the autumn of 2007. Peter and I hit it off instantly — he was so easy to get along with, as you describe in your remembrance. I really enjoyed the USSEE meeting in East Lansing, Michigan, where you and I got to spend a lot of time with Peter trading ideas as we strolled the MSU campus. Fond memories!

Amidst these chaotic times, I take refuge in the fact that highly self-aware individuals like Peter saw the limits to growth long ago and worked to ensure that this message would be carried forward to future generations through CASSE. Appreciate the wonderful tribute.

I had no knowledge of Peter Seidel, until 5 minutes ago, but appreciated this account of his life.

One point that really caught my eye, given the context, was the apparent paradox (chose that word carefully) between his values related to steady state economics and the apparent source of his wealth which, as Brian recounts, was the result of investing in the growth economy.

I’ve no desire to besmirch the gentleman’s reputation — I can certainly applaud his choices of beneficiaries; rather, I’d like to ask the honest question of how does one reconcile this apparent contradiction? Peter Seidel is but one example of this; a generalized answer to the question could be instructive.

For any reader who lost a close friend or family member, I offer sincere condolences.

Thank you Ken for this respectfully framed question.

I too would welcome a generalized, instructive answer. In my role with the Qualicum Institute

which supports the transition to a steady-state economy, I’m well aware that my government pension and retirement savings are tied to GDP growth.

None of us live lives truly separate from the faulty economic growth model. The most we may be able to do is channel the resources at our disposal toward genuine solutions.

I’m very sorry to hear about Peter Seidel’s passing. I wish I had known him.

Kind regards, Terri Martin

Well, at the time of Peter’s investments in early IT—remember this was the 1950s—hardly anyone was talking about limits to growth. Peter himself was only beginning to have such thoughts. It takes awhile for big-picture, long-term thinking to mature, then manifest in financial decision-making.

What percentage of citizens had any sort of limits-to-growth mentality at that time? At the best, there would have been something of a land ethic ala Aldo Leopold. As far as I know, Peter didn’t invest in any energy or mining or other extractive corporations. I don’t think he invested in heavy manufacturing, either.

And you have to ask yourself: What would you do have done with savings in the 1950s? Peter probably thought that IT was, at best, a potential pathway to smarter, more sustainable decision making. Yet I don’t think there was any talk of “green growth” or a dematerialized “information economy” that ever fooled Peter in the succeeding decades. Rather, I think he invested in IT as the lesser of evils, and became an accidental/incidental millionaire.

And don’t forget, as I alluded to in the memoriam, Peter was no conspicuous consumer. He had the money to live in palatial digs, but lived instead in a modest apartment with but one luxury: a spectacular view of the environmental and architectural beauty that reflected his values. He drove a Prius (by the time I knew what he drove). He went to a farmer’s market for local-grown, organic vegetables.

A man of Peter’s position would have had savings. What to do? “What to do with the savings?” This was the question posed at the Degrowth conference in Chicago this summer. It’s a topic I’ll be writing about for the Herald, following up from “Sell Your Stocks” (https://steadystate.org/sell-your-stocks-and-enjoy-the-slide/).

As far as I know, no one invested more in advancing the steady state economy than Peter Seidel. Let’s celebrate that for now.

Peter will be missed.

Thank you, Brian Czech, for that impassioned, well-informed, beautiful, tribute to Peter Seidel! And good to see the searching question of Ken Panton and the worldly-wise observations of Terri Martin about our embeddedness in economic growth. After all, it’s not just a set of practices but also an ideology with many of its supporters doing all they can to maintain its fit into our daily lives and assumed thoughts, an ideology that needs addressing especially since its impact is so pervasive.

On Peter Seidel’s generous spirit, Brian’s post is the account of record.

Considering Ken’s question as a helpful prod to strengthen the Steady State game (methinks Peter would appreciate this!) and with Terri’s observations in mind, I’ll add one more generalized response and let others consider if it is instructive, to borrow Ken’s words. My appreciation for Peter, including with the types of stocks he held, is that he served as a kind of modern Robin Hood, trading with the mainstream to support alternative paths, leaping from the present to find a better future.

From our present with ambient endorsements of constant growth, may we all find more such paths to a steady-state future—in Brian’s cheerful call for downsizing, “Sell Your Stocks,” in his promised follow up, and in more such lightbulb suggestions for coping with a complicated present. Here’s one, Climate First Bank: https://www.climatefirstbank.com/our-impact. I welcome your comments or critiques.

With thanks to all for your good work,

Paul

Everybody at any time lives off the economy. The fact that someone might live off an economy that happens to be growing does not mean they are necessarily taking advantage of a growth economy by actively investing to help grow the economy they are dependent on.

If someone invests in low throughput-intensive capital goods with the aim of replacing depreciating high throughput-intensive capital goods (no more investment than that), and derives an income from selling the useful goods generated, they are not living off the growing segment of the economy (note: ongoing investment is necessary to keep the stock of capital intact – investment does not cease in a SSE). To the contrary, they are generating an income like a true steady-stater.

My local butcher could be one of them. He proudly displays photographs on the wall of the family butcher shop from when it began in 1963. From the photos, it can be easily seen that the family business has not grown over the years. But the shop has changed as well as the meats for sale, especially the manner in which the livestock is treated and fed.

I didn’t meet or get to know Peter Seidel. He may well have generated a substantial income from his investments. Some people earn large incomes by generating and selling very useful goods and services. One can’t be critical of someone who does this, particularly if they are investing like a steady-stater, which Peter may have done. If Peter earnt a large income as a consequence of his steady-state investments, and it was beyond what many people would class as a justifiable maximum income, it’s up to governments to tax away a significant portion of the income. Governments don’t do this.

Some people earning high incomes respond by giving away a lot of their money. It sounds like Peter was one of them. If so, he may have been a steady-stater by his personal, business, and philanthropic actions, as well as by his words.

Thanks, Philip, for your prompt and good response. Now I offer my delayed support for your distinction between taking advantage of a growth economy and being dependent on it. This is an idea with legs! Many of those dependent on growth could become supporters of limiting growth but are unable to because of their dependency—hemmed in by designs by those more powerful to keep them in that role. From your good insight, supporters of limiting growth could approach these people not as antagonists but as potential future supporters. And those people could use support for even small steps to reduce their dependency on growth. Even if they are not woke, they might be waking…..

And Philip, you make another good point about taxes as a way to discourage incomes not justifiable. This points to ways that taxation is not just for raising revenue. It can also be a way to incentivize behavior. Governments can encourage positive choices and discourage negative ones. But as you say, current governments don’t do this. That would be a good goal and might even gain some bipartisan support.