Taxes, Economic “Development,” and Growth Fetishism — State of the States

by David Shreve

Many are beginning to sense that there is a diminishing relationship between increasing gross domestic product (GDP) and broad prosperity or “quality of life.” Environmental perils are a big part of this—from dying oceans and freshwater shortages to extreme weather events and epidemics. People readily feel these changes, even without knowing their true extent. Technological advances notwithstanding, there is little doubt that ongoing “growth” only perpetuates and amplifies such perils.

Growth as the path to jobs: a problematic postulate. (George W. Bush White House Archives, Public Domain)

But most national governments face a recurring dilemma: Macroeconomic policies that alleviate unemployment and poverty tend to increase output and the ecological footprint. Growth, then, frees us from one horn of the dilemma, while goring us deeper with the other horn.

But there’s another option: We can add and subtract, rather than simply adding. At the same time as stabilizing population and redistributing income, we can increase output where it matters most, yet reduce it overall. Isn’t this adding and subtracting a perfectly viable choice? And wouldn’t it establish a much more sustainable path to prosperity?

Federal policies, however misguided and unsustainable, do bring additional jobs and opportunity, and they deserve empathetic criticism. State development efforts, on the other hand, have largely done no such thing. Their development programs have been futile and environmentally destructive, yet with few jobs to show for them.

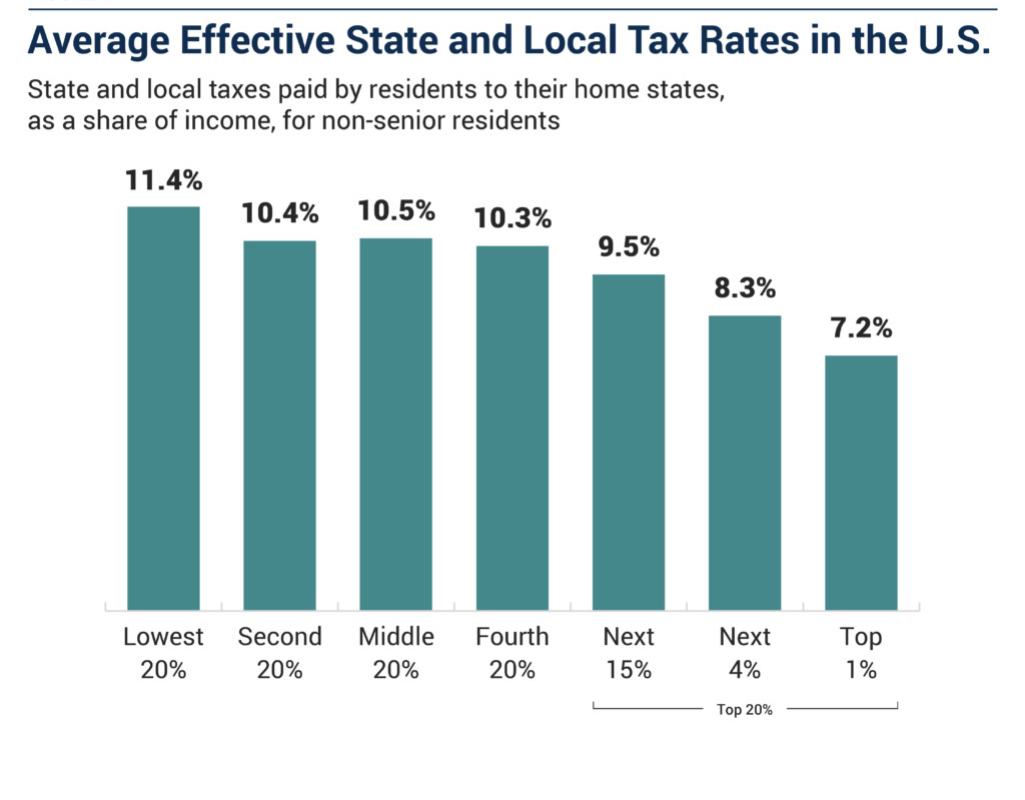

If the nation fails to redistribute wealth and invest in public goods sufficiently, or engages in unsettling “stop-go” monetary policy, no one state is equipped to offset the effects. Furthermore, states themselves routinely push hard in the wrong fiscal-policy direction, taxing the poor proportionately more than the rich.

As for employment, most marginal job creation (adding) in the United States stems from federal policy. For example, in the Great Depression and the Great Recession (of 2008-09), federal fiscal stimulus offset substantial job contraction at the state level.

Still, if states change their approach to taxation and “development,” they might develop the right kind of policy teeth for sustainable adding and subtracting. They can become an important piece of the steady-state puzzle.

Upside-Down Taxes

No U.S. state possesses a progressive tax structure. According to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “The lowest-income 20 percent of taxpayers face a state and local tax rate nearly 60 percent higher than the top 1 percent of households.”

All state tax systems are upside-down. (Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy)

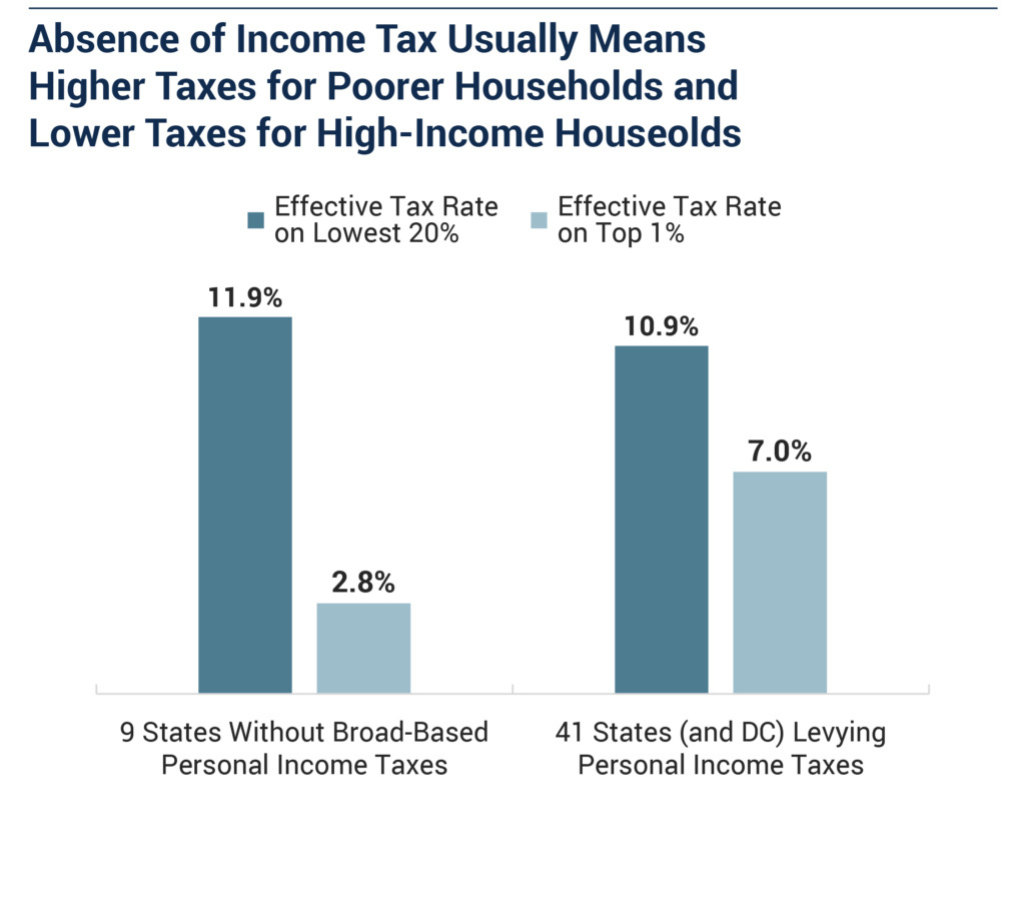

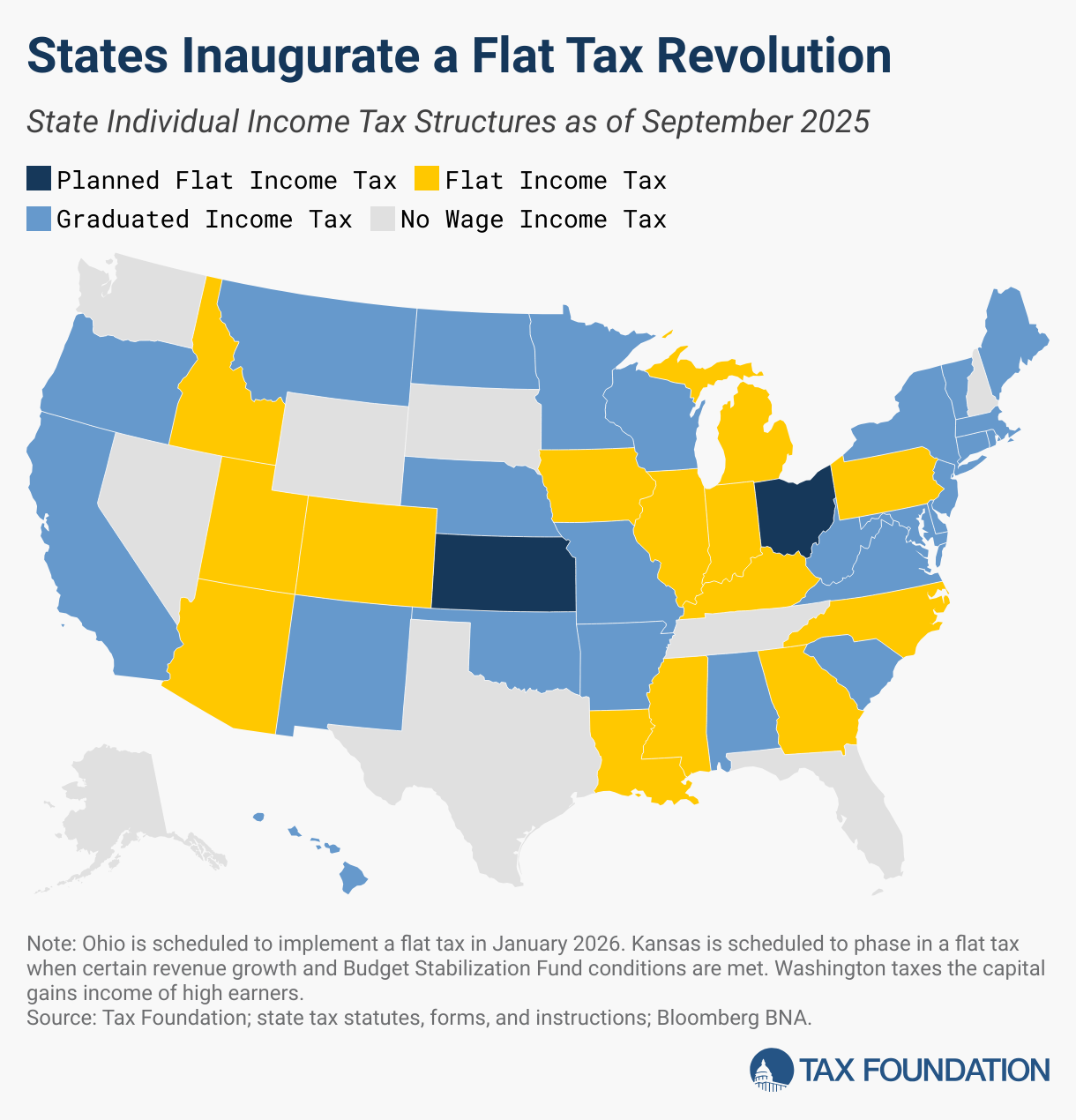

Nine states have no income tax. Fifteen have flat income taxes, with no graduated brackets. An additional twelve states have effectively flat tax structures, with extremely low income thresholds to be counted in the top bracket. In Virginia, for example, the highest rate kicks in at $17,000 in taxable income. Almost everyone pays the highest rate.

All states count on sales taxes, excise taxes on specific goods or activities, and fees. Collectively, these require the poor to pay a larger share of their income than the wealthy.

States do offset these upside-down taxes with somewhat progressive spending on public goods and safety-net programs, but only modestly and often incompletely. These programs benefit all, but the poorer the citizen, the greater their value. Ironically, many leaders feel that if they’ve enhanced these progressive programs, it’s okay to pay for them with insufficient and unsustainable regressive taxes.

When it comes to poverty reduction, under the status quo, states are at best neutral factors, and in many cases, they generate economic headwinds. Without a sufficiently progressive federal partner, joblessness and poverty increase. Pledges to solve the issue with “growth” prevail.

Misguided “Development”

State tax systems without income taxes are especially upside-down. (Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy)

Facing job deficits with little power to fix them, most states concoct ambitious economic “development” programs. Their rhetoric is invariably bold, even if the details are vague and simplistic. Claims for “success” in these ventures are seldom well-defined. By their very nature, these programs almost never increase aggregate employment. Some new jobs may be created, but economic cannibalism, environmental degradation, and diminished quality of life are the more common products.

Boiling it down to a simplistic recruitment of employers and the economic growth they associate therewith, states still shoot for the moon. In May 2025, Alabama Governor Kay Ivey signed a Powering Growth plan, which includes “developing more move-in-ready industrial sites.” Louisiana leaders recently passed a similar Positioning Louisiana to Win program, designed to “better attract new business.” Indiana launched EDGE—Economic Development for a Growing Economy—which leans heavily on business tax credits. The vague promotion of “growth,” almost always conflated with bona fide prosperity, is everywhere.

On occasion, policymakers sense problems with these poorly conceived programs. Most states have long exceeded key growth thresholds, past which further growth causes more problems than it solves. Whether portrayed as “smart” or not, it comes with mounting social, environmental, and economic costs. The per-capita costs of governing now routinely increase along with growth.

When Tennessee passed its Growth Policy Act in 1998, it also recognized the need to arrest sprawl and preserve undeveloped areas. Like similar initiatives in a few other states, however, this one mostly passed the buck to localities. Penalties for local non-compliance, proven ineffective, were eventually eliminated. “We still want you to grow,” state leaders seemed to be saying, but please, somehow, “just say no” to the maladies that come with it.

Seeking Jobs and Opportunity; Getting the “Squeeze”

State subsidies for “development” abound. A rising number of states have also jumped on the tax-reduction bandwagon, seeking the same illusory goals. Business recruitment is the initial goal; “jobs, jobs, jobs” is the ultimate prize.

But the results are usually dismal. Trickle-down still disappoints. New jobs happen in some places, but they tend to represent little more than a reshuffling of the national or regional deck. What’s more, most are taken by migrants to the state or locality, not by unemployed or underemployed residents.

Governor Ivey, “powering growth” and squeezing Alabamians. (Melanie Rodgers Cox, Public Domain)

States routinely treat general tax cuts as a means to “development,” assuming they will benefit all types of enterprise. Instead, new enterprises tend to cannibalize established ones. Small independent enterprises lose out to big oligopolistic ones. Tax bases are strained. Inevitably, some wealthy localities respond with their own tax increases. Yet, because the taxes they deploy are regressive, the costs of growth are addressed mostly by squeezing again the jobless and needy.

Feeling the need to insulate some citizens, localities occasionally opt for special taxing districts. These limit local tax increases to special areas, often to improve infrastructure and service support for recruited enterprises. But special taxing districts are often gimmicky neutron bombs. They increase government debt, decrease accountability, and cater only to the large oligopolistic enterprises that can (at least temporarily) absorb the new charges. Other enterprises are quietly euthanized, and many residents are displaced or locked out.

The Mounting Costs of Growth

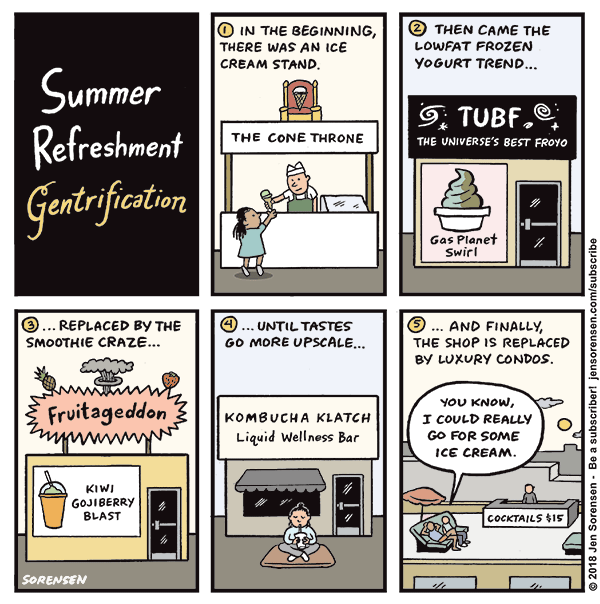

The “gentrification” cost squeeze is bigger than just real estate. (Reprinted with permission from Jen Sorensen)

New corporate recruits and associated jobseekers usually have much greater wealth than the “mom and pop” stores and residents they often displace. The principal “growth” one gets, therefore, is the growth of local costs. Inflated real estate prices, higher (and regressive) property taxes, and stressed public infrastructure are among the most common of these.

Blamed increasingly on restrictive zoning, real estate price increases are intensified by “attract-big-employers” development, whether induced privately or publicly. The same can be said for the cost of living in general, raised by the comparatively greater demands of wealthier newcomers. Towns looking for a little economic boost get rent increases and twenty-dollar hamburgers instead (and a higher sales tax on those hamburgers).

These cost-of-living increases, coupled with the downgrades in public services that often accompany business tax cuts and regressive taxation, generate a vicious cycle of inequality and displacement. The cost of environmental degradation usually grows, too. Often difficult to detect when it begins, such degradation is commonly ignored until it presents a crisis.

Nascent stormwater management squabbles illustrate this well. Up to a certain point in a community’s evolution, Mother Nature provides this vital service at no charge. Beyond that point, it cannot, and taxes must be raised. It’s difficult to understand why these (habitually regressive) “rain taxes” are necessary; they precipitate much more rancor than remediation.

What Should States Do?

In light of these dismal conventional results, what should states do about economic-development initiatives that compromise quality of life and sustainability? The first step is for state policymakers to look at the broad picture. They would find few unqualified success stories, where the jobless found jobs, communities sustained a high quality of life, and the targeted region didn’t overstep its environmental carrying capacity.

With this “revolution,” we “ain’t gonna make it with anyone, anyhow.” (Tax Foundation)

The broader picture also reveals how growth forces states to borrow biocapacity from neighboring states, all of whom are preparing to do their own borrowing. In many regions, this borrowing of disappearing biocapacity has already reached alarming levels. Counted on for clean air and water in neighboring regions, forests in developing places disappear. Counted on for freshwater across state boundaries, major surface sources and aquifers shrink and become more expensive to tap.

Expensive real estate forces longer commutes, pushing one community’s ecological footprint into another. Past a certain point, commutes become infeasible and labor mobility is hampered, exacerbating regional inequities and economic inefficiency.

Recognizing its costs, states might roll back conventional economic development policy. Unusual circumstances, like the closing of a historic factory in a community with a workforce well trained to do that factory’s work, might warrant an exception. Indeed, it is mostly, if not only, in places like this where conventional economic development has generated mildly positive results. Manufacturing “replacement” projects can occasionally produce net economic benefits. Most states playing the game today, however, are not facing such a simple challenge.

From Laboratories of Regression to Progressive Partnership

Justice Louis Brandeis once called U.S. states “laboratories of democracy.” The experiments have hardly been progressive. (Harris & Ewing, Public Domain)

All states would achieve more sustainable prosperity by fixing their fiscal policies. The goal should be to work with and not against the federal government, especially under administrations that recognize the nation’s biocapacity and its latitude for progressive change. Modern economies can’t survive without planning and progressive fiscal policies, which also ensure full employment without the costs of growth-first development. Full employment can be achieved at any level of overall output. With policies geared to population and workforce-participation needs, we need not depend on growth.

Alongside negative fertility trends, which reduce full-employment targets, improved fiscal policy can reduce workforce participation by enabling people to choose more leisure and less paid employment. With the federal government leading the way, states can accept reduced economic output without having to fret endlessly about compromised prosperity.

If, however, states continue to push for growth and assume it is a key part of any economic solution, unemployment will persist. And so will the tendency to remedy this crudely with more economic output, however it might be obtained. This “tail-chasing” behavior, and the senseless growth targets that drive it, must be eliminated.

The Key “Development” Principles

Taxing and spending—not just with “crumbs from the table” but with genuinely progressive structural change—must function as an engine of large-scale redistribution. To finance public investments that enrich the lives of all citizens, rich or poor, state tax systems need a major overhaul.

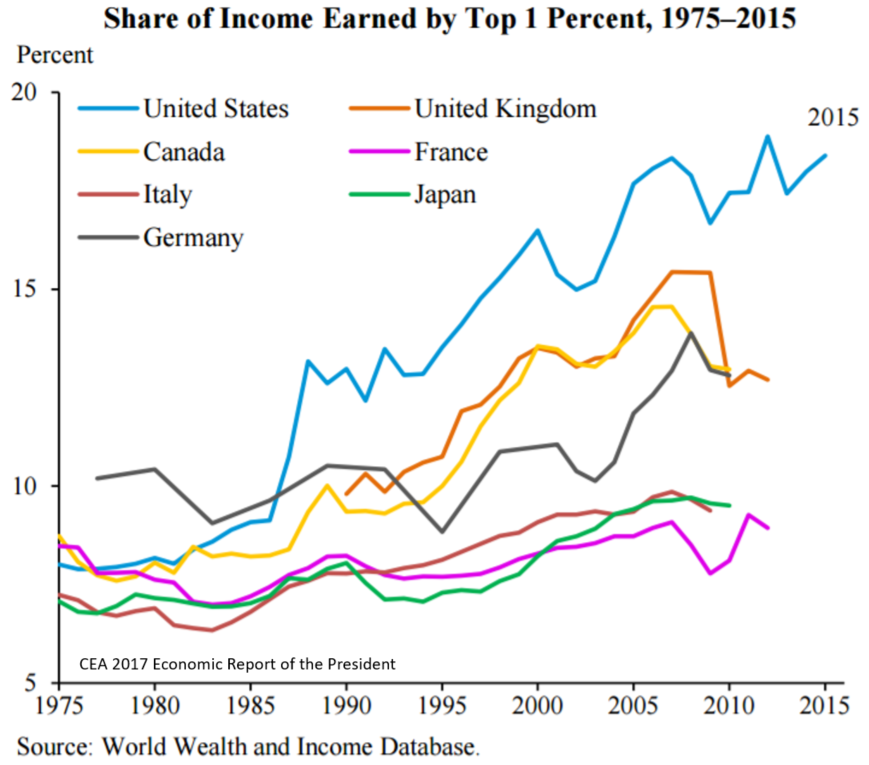

Flattening this American curve is a better “development” policy. (U.S. Council of Economic Advisers, Public Domain)

This is true not just in states with miserly, reactionary governments, but in all of our nation’s fifty states. Red or blue, all function currently with regressive, unproductive, and economy-stifling fiscal policy. Remedying this is not simply a matter of more funding for good programs, but also of putting income of diminishing utility back to work in the economy. By allocating more spending to necessities and away from luxuries, and transforming idle savings and “boom and bust” speculation into steadier exchange, communities can achieve more well-being (and employment) with less material throughput.

If state policymakers and residents can’t see the forest for the trees and keep rolling out conventional development programs, their smarter colleagues should move to rein them in. Otherwise, few who are lacking jobs and economic opportunities will get them. And the costs borne by all will continue to mount, in terms of dollars and environmental degradation.

Especially for states, growth seldom delivers on its promise, eliciting repeated calls for more of the same. But “more” only exacerbates the problem. If instead states encourage the nascent fertility transition and embrace the stabilizing wealth redistribution that comes with sounder fiscal policy, they can achieve widespread prosperity without growth. And they can trade Pyrrhic “development” victories for genuine ones.

David Shreve is a Senior Economist at CASSE.

David Shreve is a Senior Economist at CASSE.

Thank you for this. All I can add: it would be great if states had quantitative measures of human well being, as well as GDP. Although this would need to be done by outsiders (maybe WHO?) to keep it a matter of apples vs. apples.