Paying Taxes with Trophic Money: Watch Out for Environmental Backfires

by Brian Czech

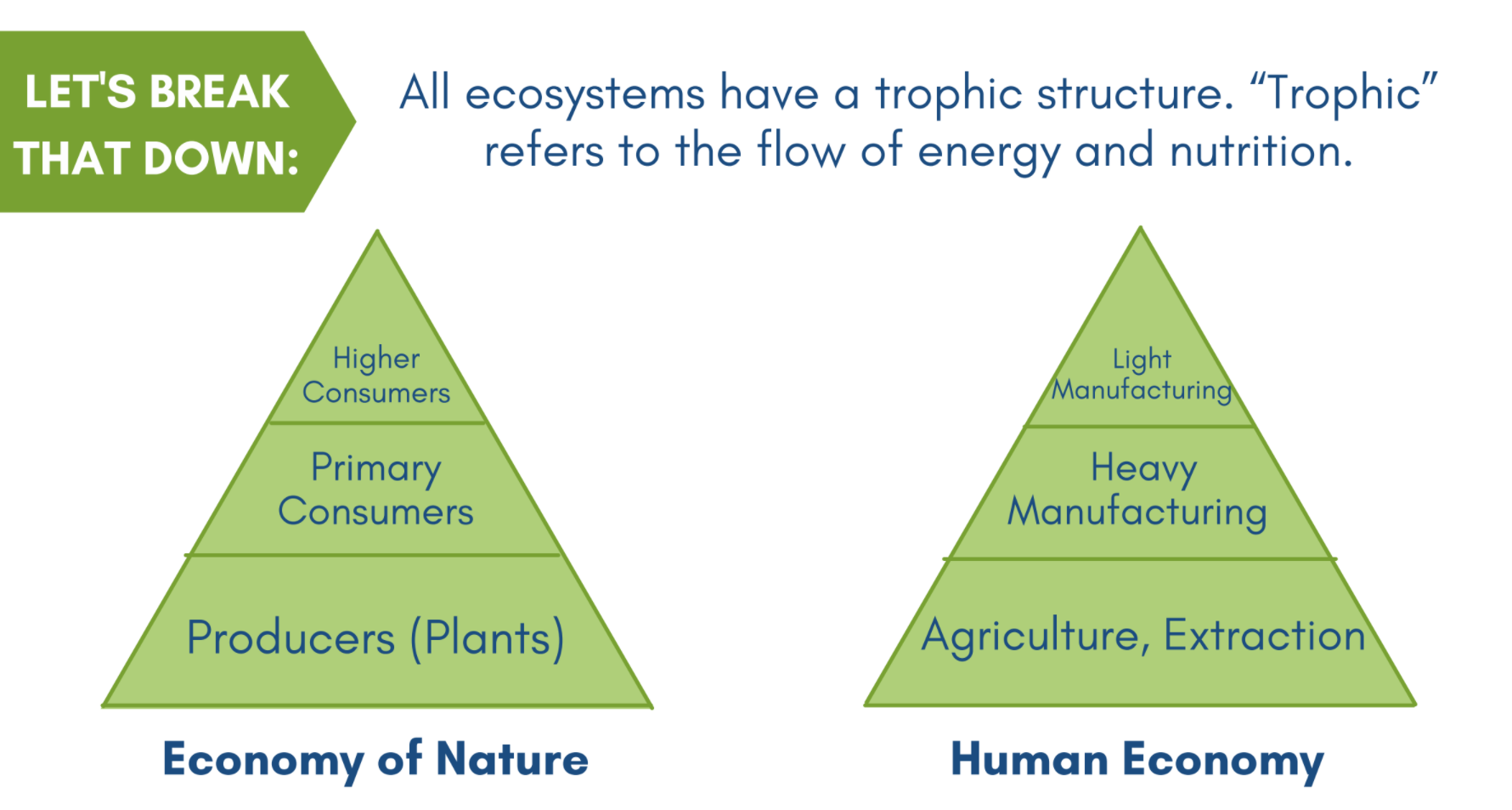

I didn’t set out to coin a phrase, but “trophic money” will be far handier than “money derived pursuant to the trophic theory of money.” The trophic theory of money is that money originates via the agricultural surplus that frees the hands for the division of labor into all the other economic activities, most basically manufacturing and services. It’s a theory of money that reflects not only the trophic structure of the economy—with manufacturing and services built upon a base of agriculture and extraction—but the fact that money is meaningless unless we have an agricultural surplus at the trophic base.

No surplus, no money. This explains why money originated in regions equally known for the origins of agriculture and predictable food surplus (for example, Mesopotamia, Lydia, and the Yellow River basin of China). It also explains why some of the first records of environmental deterioration come from the exact same regions (most notably Mesopotamia and the Yellow River basin).

The reason, then, for referring to “trophic money” is to keep in mind this trophic structure, and the fact that truly “generating” money entails an ecological footprint. In fact, corollary number one of the trophic theory of money is that the quantity of money—and GDP—indicates the amount of agricultural surplus and related activity at the trophic base of the economy. “Related activity at the trophic base” includes the extractive activities such as mining, logging, and commercial fishing.

A CASSE infographic on the trophic theory of money.

In other words, GDP is a solid indicator of environmental impact because, as a measure of trophic money spent, it’s a measure of the agricultural/extractive footprint.

Using the phrase “trophic money” in sustainability writing is analogous to using the phrase “fiat money” in economic justice writing. At this point in history, almost all money is fiat money, especially in the narrow sense that legal tender is no longer backed by gold. The adjective “fiat,” then, is hardly essential. Yet many authors favor the phrase “fiat money” in order to drive home the point that bankers have an unfair advantage over everyone else.

The adjective “trophic” trumps “fiat” in the salient sense that all money is and must be trophic money. No money originates in the absence of agricultural surplus, and no money retains value (or even relevance) in such absence.

A Primer on the Philosophy of Taxation

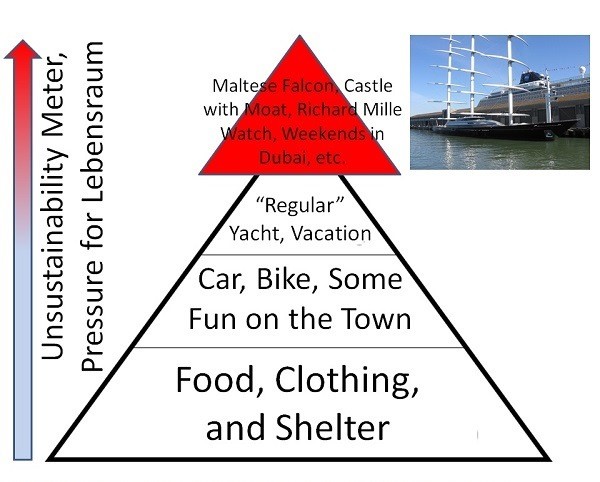

Taxes are commonly used to incentivize or, more directly, disincentivize certain behaviors that society has come to recognize as undesirable, unseemly, or unsafe. Of course, taxes are also used for generating public finance. Alongside the federal budget, the tax code comprises fiscal policy and, in an ideal democratic world, reveals a wealth of information about the values we share.

In the hands of liberal politicians—and as conservatives love to lament—the line becomes blurry between disincentivizing bad behavior and generating money for pet projects. Yet liberals often defend certain taxes (especially on the rich) on the grounds that they will actually spur GDP growth. Liquor sales might contribute to GDP, but an alcoholic public is unproductive. Therefore, the argument goes, we should tax alcohol not only to protect the health of drinkers and the lives of innocents (such as drivers and pedestrians), but also to grow the economy faster! If you’re a steady-state liberal, you’re probably for the former and certainly not for the latter. (If you’re a steady-state conservative, you’re for neither.)

All taxes are not created equal. (Image: Pixbay License, Credit: wal_172619)

When it comes to the environment, things get a little more complicated. Environmental problems such as pollution and habitat loss are considered “negative externalities.” No one pays the costs of pollution in the market. Rather, we all pay—often with our health—outside of, or “external” to, the market. The costs are diffused, in other words, among the general public, while the polluter accrues all the financial benefits of the polluting activity. Taxes are often prescribed, then, to “internalize” the costs of pollution. A tax on carbon is the most prominent example today.

With Sustainability and Justice for All

Environmental taxes help to rectify the injustice of polluters profiting at the expense of the public. In a nation priding itself in the maintenance of justice, you might expect to see environmental taxes passed left and right. They are not, however, because of a systematic political challenge; the benefits of polluting activities are concentrated while the costs are diffused. Not only that, but the benefits are concentrated in the hands of powerful, lawyered-up corporations while the costs are diffused among a collection of “little guys,” individual citizens.

This “diffused costs, concentrated benefits” policy arena puts corporations and pro-growth interests at a huge advantage. They are motivated to retain their profits and power, fighting against any challenger if need be. Meanwhile, very few of the little guys and gals—busy as they are (often working for powerful corporations)—are motivated to fight for the bit of environmental improvement their efforts might possibly lead to. The little guys aren’t politically stupid, either; most of them realize it will take concerted action by a large number of compadres to make any difference in the activities of the polluting industries.

Furthermore, in many cases of pollution it’s not at all evident how bad the problem is. Hardly anyone knew about the ravages of organochlorines (such as DDT) until scientists at the University of Wisconsin somewhat luckily stumbled into organochlorines as the culprit that nearly extinguished the bald eagle, the peregrine falcon, and other ornithological icons. Similarly today, how many of us have even heard of endocrine disruptors? Maybe you have, thanks to scientists such as the late Theo Colburn (also the founder of TEDX). But, can you spot one in your environment? Can you feel what the lot of them is doing to your nervous system? Can you diagnose your problem and trace the source all the way back to the polluter(s)?

Of course not. Frankly, it takes a whale of an education these days just to keep abreast of the chemical threats to the environment, wildlife, and human health. Who’s got the time and money for that?

It all sounds really unfair, doesn’t it? The fate of posterity might just rest in the hands of highly educated and sincerely motivated little guys and gals who assemble for purposes of constructing class-action lawsuits and lobbying for environmental taxes!

Into the Teeth of the Trophic Conundrum

Alas, even if we succeed in passing a very broad sweep of environmental taxes, we still have a problem. What if those corporations are so driven by revenue that they decide to actually pay all the taxes entailed by their polluting activities? In other words, they are not disincentivized from such activities, but rather incentivized into more such activities simply to pay the taxes without losing net revenue.

And of course, they’ll be paying the taxes in trophic money, as all taxes are, because all money is trophic. Sensing the problem?

Now, let’s consider a less obvious challenge. Let’s say those corporations are indeed disincentivized to some degree, such that their polluting activity declines somewhat. They also have to pay the taxes corresponding with the remaining polluting activity. How do they do that? A smorgasbord of cost-cutting measures might come into play, but that will only get them so far. Chances are these corporations will be incentivized by the tax burden to develop additional product lines or service activities. In other words, they will try to retain or increase the level of profits they had prior to the enactment of the tax. If anything, their economic activity will amount to an even higher level, because now they need the additional income to pay the new tax.

Income, of course, in trophic money.

Through the ecologically clouded lens of neoclassical economics, and with no understanding of trophics, this scenario would be considered a “win-win.” We lessened a pollution problem without impacting profits, and we generated public finance! Yet through the lens of ecological macroeconomics, especially the trophic theory of money, we’ve robbed Peter to pay Paul, probably while polluting just as much, and certainly while being pressured into more agricultural and extractive surplus at the trophic base.

Who’s Peter and who’s Paul? Peter is the polluting industry. While it ended up maintaining its profits, it took a lot of effort, reinvestment, and probably a little luck. Paul is the government, which now has bigger coffers for government expenditure, also known as consumption.

Paul has more trophic money now, while Peter has about the same. The net effect is GDP growth; that is, more environmental impact at the trophic base of the economy.

Why did we probably end up polluting just as much? Because the corporation had to conduct other types of economic activities to compensate for the partial loss of its original activities. So, for example, the corporation isn’t pumping out as many PCBs, but now it’s emitting more greenhouse gases.

Most importantly for our purposes, neither Peter nor Paul can be considered in isolation of the broader economy, its tax code, and its trophic structure. For the economy at large, Peter is essentially the entire supply side; agricultural, extractive, manufacturing, and service sectors all bundled up in their respective trophic levels. Paul is government in the aggregate—federal, state, tribal, local—and is a major contributor to GDP.

With all the production, consumption, and taxes being paid for with trophic money.

Environmental taxes can backfire in the fast lane of GDP growth. (Image: CC BY 2.0, Credit: Chris Waits)

If the tax code is replete with “environmental” taxes that actually stimulate the Peter-Paul complex into even more economic activity—GDP growth in other words—we wind up with less biodiversity, more congestion, higher levels of stress, etc. ad nauseum. We wind up closer to limits to growth, in other words. That’s the trophic conundrum: Levying environmental taxes leads to the environmental impact incurred in the process of generating the (trophic) money to pay the taxes.

I am not saying environmental taxes are always and everywhere a bad idea. If they lead to a substantial reduction of a carcinogen, for example, well, that speaks for itself. Clearly, however, the trophic theory of money poses a challenge for economists to develop some ecological rigor in assessing the marginal benefits of environmental taxes.

Perhaps some taxes will not only disincentivize particular polluting activities, but also tap some brakes on GDP. That would be steady-state fiscal policy. It’s up to economists, ecologists, and ecological economists to identify the conditions under which a tax may serve for brake-tapping purposes, in addition to crimping the stream of a particular pollutant.

We can wish it weren’t true, but all money is trophic money. In lay terms, you can’t buy your way out of environmental impact and limits to growth. You might be able to tax your way closer to a steady state economy, though.

People have wrestled with theories of money and taxes for millennia. Silver appears to have been in use for about 5,000 years. In comparison, fiat currency is a relatively new experiment… and it’s not going well… except for a very few at the top of the pyramid. Some individuals even have tried to formulate a theory of a moneyless society. That sounds appealing, but no one yet has succeeded in selling their idea to the world as a whole.

My background is in agriculture, geography, and ecology. In spite of that, until now I’ve never considered the trophic nature of money. Amazing… that I haven’t. THANKS for this article, and KUDOS. It’s a meaningful contribution to grasping the complexity of ecology, economics, and government. It also demonstrates the folly of neoclassical, mainstream econ in terms of their claim that Nature is not important in economic matters.

Thank you so much, Scott. I have often thought that, of all the ecological concepts unknown to (the vast majority of) economists, trophic levels are most important. They tie the thermodynamics lessons of Georgescu-Roegen directly to the economy of nature and its subset, the economy of Homo sapiens. Trophic ecology is the natural complement to Herman Daly’s emphasis on throughput and time’s arrow, with entropy governing the dissipation of energy and biomass from one trophic level to the next.

I’ve had the experience of arguing about limits to growth, including in formal debates, with many economists over the decades. It struck me every single time that they lacked grounding, so to speak, in trophic levels, and that they would have “gotten it” if they had such grounding. Therefore, trophism is, I believe, a crucial element of ecological macroeconomics. (So much so that CASSE will be modestly supporting a small number of research fellows to help build upon the trophic theory of money.)

Amen, I couldn’t agree more. Be Well

Brian: “Frankly, it takes a whale of an education these days just to keep abreast of the chemical threats to the environment, wildlife, and human health. Who’s got the time and money for that?”

Me after spending £45k+ over 16 years on 3 degrees and a GDL : https://i.giphy.com/media/jUwpNzg9IcyrK/giphy.webp

All jokes aside; a great article, Brian. One which focuses on just *one* of the myriad economic/ecological clashes we’re going to have to consider if we’re to have any hope of mitigating the effects of climate change.

Unfortunately, the scale of the task at hand is made abundantly clear by the continued apathy displayed toward engagement with (read: the assumption of responsibility of) such issues, from crucial actors.

Just this morning, for example, I read that the UK’s Committee on Climate Change are still championing the idea that individual behavioural change is key to achieving a net-zero target. Of course, this would be well and true if we had the time (often decades) to *wait* for the kind of fundamental individual behavioural change required to manifest itself, but we obviously don’t. In that light, their insistence that “pursuing an approach that only focuses on supply-side changes” is insufficient … well, it smacks more than a little of kicking the can down the street.

To borrow your analogy, it seems to be letting both Peter *and* Paul off the hook, yet again at the expense of us “little guys” (who they get to blame too, for good measure!) when it inevitably goes wrong.

Prof. Brian Czech’s article is nteresting but I am not entirely following his logic:

“If the tax code is replete with “environmental” taxes that actually stimulate the Peter-Paul complex into even more economic activity—GDP growth in other words—we wind up with less biodiversity, more congestion, higher levels of stress, etc. ad nauseum.”

Assume that society:

– taxes the purchasers of concrete, not the manufacturers of it, since concrete emits huge amounts of CO2 during construction;

– spends less money buying concrete since:

– alternatives to it become more cost competitive;

– subsidizes through tax credits purchases of laminated beams made out of lumber from sustained yield forests which store CO2;

– requires the manufacturing of the laminated beams be powered by electricity from hydro, solar and wind and not hydrocarbons;

– schedules the subsidies to expire after a certain duration of time or production per company so that economies of scale can take place;

– due to market signals (net prices), spends less money building with concrete and more money building medium and high rise buildings with laminated beams;

Would not:

– total GDP stay the same or even increase (due to the high need for housing) but

– much less CO2 be emitted as a result of these changes in construction methods?

What is wrong with this scenario that involves a lot of economic activity using sustained yield forestry?

Is not the world is much better off even though GDP may increase?

Also, if ever more GDP is created by such things as art, video games, software and electronic books, newspapers and magazines, for example. how is this creating less biodiversity, more congestion, etc.? Is it not creating good and well paying jobs and outlets for our creativity?

So I don’t get this obsession with reducing GDP since measuring GDP seems to not differentiate the relative impact of various economic activities on our environment.

Cheers,

Chris

Chris, I’ll post a reply in two parts (due to the word limit):

As I stated, “…neither Peter nor Paul can be considered in isolation of the broader economy, its tax code, and its trophic structure. For the economy at large, Peter is essentially the entire supply side; agricultural, extractive, manufacturing, and service sectors all bundled up in their respective trophic levels. Paul is government in the aggregate—federal, state, tribal, local—and is a major contributor to GDP.”

I added, “With all the production, consumption, and taxes being paid for with trophic money.”

The point I’m making here is that we can’t get to the bottom line of sustainability by hypothesizing about microeconomic scenarios. Rather, assessing the implications of taxes—more importantly the tax code in the aggregate—has to account for the entire “trophic ecosystem” of the economy.

Now you might object, “Well, you [I] used microeconomic examples, too.” And I did, such as the trade-off between PCB and greenhouse gas emissions. But, I used them as examples (not as stand-alone arguments) supporting the ecologically macroeconomic conclusion that taxation helps toward sustainability only if it helps curb GDP growth, given that GDP is a measure of environmental impact. ( https://royalsoc.org.au/images/pdf/journal/152-1-Czech.pdf ) And, I don’t see any fatal flaws in the use of the examples, do you?

I don’t see that happening with your argument. You provide a couple of microeconomic scenarios in isolation of the trophically structured whole, and leave it at that. Furthermore, there is a fatal flaw in the argument, if you are trying (as it seems) to posit a scenario of perpetual GDP growth, because the “sustained yield forestry” you tout is sustainable, by definition, only by the very limitation thereof.

Answer to Chris (cont.)

Finally, you cannot have an economy in which the proportion of GDP contributed by “such things as art, video games, software and electronic books, newspapers and magazines” is perpetually increasing. Why, that’s the whole point of the trophic theory of money. There is some elasticity in the proportions, but GDP growth entails the expansion of the agricultural/extractive base (including yield-forestry).

If you don’t want to read the article laying out the trophic theory of money (https://royalsoc.org.au/images/pdf/journal/152-1-Czech.pdf ) the video is an option:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AyUKjcEp1Jc

Finally, additional related answers (provided with an attitude, I confess) are here:

https://steadystate.org/limits-to-growth-stuff-value-gdp/

Thank you for thinking about these things.

Why would one consider human activity beyond growing food, as negative? We should be choosing electromagnetic energy over toxic battery-powered, and dangerous solar options. We’d have to cover the entire landmass of the U.S. with solar panels to replace fossil fuels, and the reflection of sunrays from panel surfaces actually create temps close to 1000 deg F at points in mid air that burn and disintegrate birds. God forbid AIRPLANES should fly through one of these beams! Windmills, also unreliable and costly to repair, are killing all the large seabirds on Britain’s east coast along the English Channel! Return to use of natural products, rather than synthetic ones, and all of the trinkets we make ourselves would simply return to the food chain.

Everything eats. That’s how the food chain works. Nothing biological is waste or pollution if it’s spread out properly to reach the hungry mouths that need it. Why our govt-run sewage treatment is based on cold composting, when all of nature uses HOT composting is beyond me. Hot composting is antiseptic, antibacterial, kills worms, takes toxicity out of heavy metals, and creates soil that makes plants more drought and pest resistant without pesticides!

The problem seems to me to be that “whale” of educational ignorance that people are trapped in. Biologists don’t learn physics or probability & statistics, so they fail to see the wonder and beauty of the created universe. Chemists don’t take geography. Geographers don’t take biology, and none of them go outdoors for any length of time it seems. Labs are not good sources of information. Their focus is too narrow to make any connections to the real world. The world is much more informative.

Australia had a massive plague of rats/vermin a few years back. That, to me, wasn’t a plague, it was an opportunity to trap rats in large freezers, and then sell them as freeze-dried food for the avian and pet food industry. Who listen’s to me?

We are carbon-based life. Everything we eat and interact with is carbon-based. There is no more clean way to return carbon to the earth for plant food than burning trash. It’s just another opportunity to recycle the materials back to the source for consumption. India is greening now because fossil fuels and air pollution are distributing food through the air to the soil.

Poverty is hell, and poor people only growing subsistence food cannot deal with any environmental problems. They cannot recover from natural disasters – a primary challenge to sustaining a society. The single greatest factor lifting most of the 3rd world out of this misery is the introduction of oil/natural gas-powered energy. No more freezing in winter, no more heat exhaustion deaths. Power to run big equipment for clean up after monsoons and cyclones. Natural gas’s only by-product is water vapor! What’s wrong with that? When India started getting electrical power, her people were able to clean up the ground pollution and dig safe deep wells for drinking water. Everywhere people use their heads, the land becomes more productive, and we still only use 3% of the surface of the land on earth. And eventually, we’ll figure out better ways to deal with trash. For instance, the floating trash mat in the Pacific is just waiting to be melted back into fuel oil for someone who wants to provide service refueling boats at sea!

My thing is, every problem has a solution, but people don’t know how to find others who could use their by-products as a resource/raw material, so the unwanted by-products become “pollution”. Every chemical action has an equal and opposite reaction. One man’s waste product is another man’s raw materials. Why can’t we find a way to list needs online and increase trade while ending trash and by-product pollution completely??? Got something left over? Someone needs to make a site that lists stuff by chemical components that others can look up and trade or purchase!

we want regulatory controls to direct a trend towards more sustainable economic activity;

meaning that a shift in activity should unlock a span of potential for growth that’s not harmful;

accelerating emerging technologies and enriching and connecting developing commmunities.

this would be the internal transformation of industry principles

manipulating economic pressures should advantage localised and socially conscious organisations.

this could mean the actuality of corporate decline in scale and influence

good growth and corporate decline are solutions to the ecological risk of trophic surplus

trophic stasis is the steady state aim

My own original idea is that (‘trophy’) money is the root of all evil.

while it formally may have begun in mideast area and agriculture, its roots lie when the humans–under the influence of their financial advisors called ‘snakes ‘ got into sinning—developed a taste for apples, land and property and decided to plant apple trees in ‘a land without a people for a people without a land’ called north america (columbus was their guide, and johnny apple seed their agriculturalist).

The humans had also developed besides a sense of entitlement,and one of superiority—so they didn’t like the chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorilllas in their family. said ‘we gotta get out of this place, if its the last thing we ever do.’ . so they left africa for n america (stopped by a few places along the way–europe, asia…) .

They had heard NYC city and SF were the places to be, as well as the ‘city of brotherly love’ (some call it ‘killy philly’–over 60 homicides there so far in 2021 compared to only 33 in DC).

Besides switching their preferences from bananas to apples and bread –cooked and cultivated food which is civilized— not rabbit food which is for lowlifes— the humans made a hierarchy beyond just faunas for ‘precious metals’ –so gold was #1. this is why they went west to the gold rush https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ishi_Wilderness (this is one gold mine i found and own) . i also have some in Klondike/Yukon. There is also ‘black gold’ you can get in WV, ND , wyoming, tar sands and gulf of mexico.

With technology one can turn black gold into white heat (see the academic song by velvet underground) and brown sugar –academic songs by rolling stones and VU (‘when i’m rushing on my run, i feel just like jesus’ son’) and then go to mideast for more black gold and religious events (crusades), cultural, and sports festivals (i’m going to world cup in Qatar to play but i have to figure out what trophy i’m going to win).

Was discussing this with a fellow researcher in EE, Shaun Sellers, some general thoughts and questions came up:

– Under conditions of monopoly, ecological taxes are less likely to affect the process of production. In a monopoly, extra trophic pressure exists because, of course, the polluter can opt to pay. Big polluters can pay; smaller enterprises can’t.

– When taxes are designed to internalize negative externalities that the polluter is not materially responsible for, then one simply ends up creating a new or bigger market, which amplifies and permits the logic/ideology of growth and marketization.

– Putting pressure on the consumer to change their behaviour with ecological taxes leaves the relationship between supply and demand very muddy in a highly financialized global economy where indirect costs are already hard to account for. The consumer doesn’t necessarily know or care about where price pressure comes from.