A Dry Reckoning for Finney County

by Dave Rollo

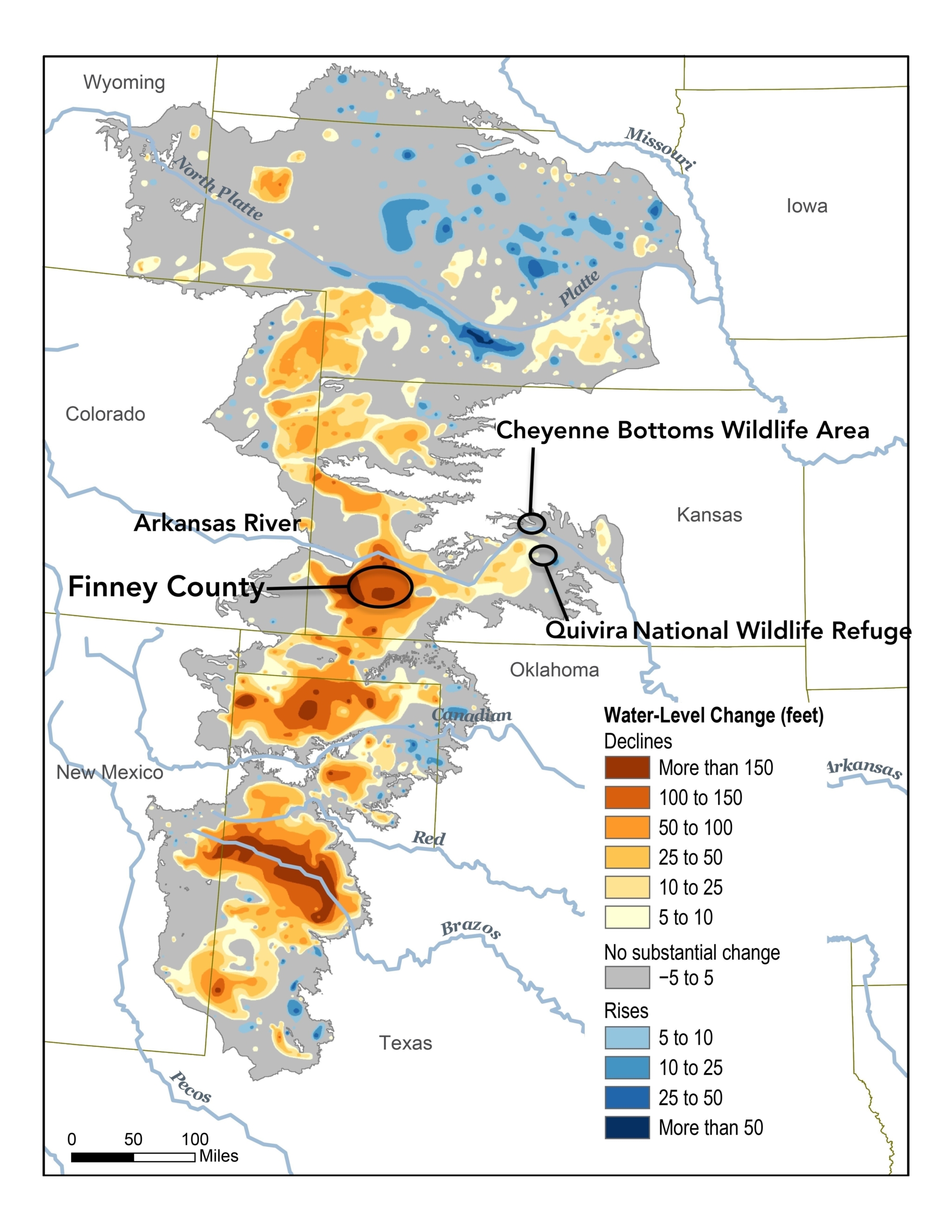

Finney County lies in the southwest quadrant of Kansas and above the massive Ogallala Aquifer. Running mid-continent from the Dakotas to Texas, the Ogallala is the largest aquifer in North America. Once holding the volume equivalent of Lake Huron, the aquifer was first tapped for high-volume irrigation in 1909. This fundamentally transformed the landscape from ecologically diverse tallgrass prairie to energy- and water-intensive monoculture crops on an immense scale.

The massive Ogallala covers 174,000 square miles under eight states. 80 percent of residents living above the aquifer rely on it for drinking water. It supplies almost one-third of the groundwater used for irrigation in the United States. Hundreds of U.S. counties—including Finney County—are dependent on the Ogallala for agriculture.

A portion of Finney County from the air. The largest circles are about a mile in diameter. (Google Maps)

The marks of Ogallala extraction are unmistakable. Circles of monoculture crops, the result of center-pivot irrigation, appear as a pattern across the landscape. The pattern is easily identifiable from satellite imagery and visible from commercial aircraft.

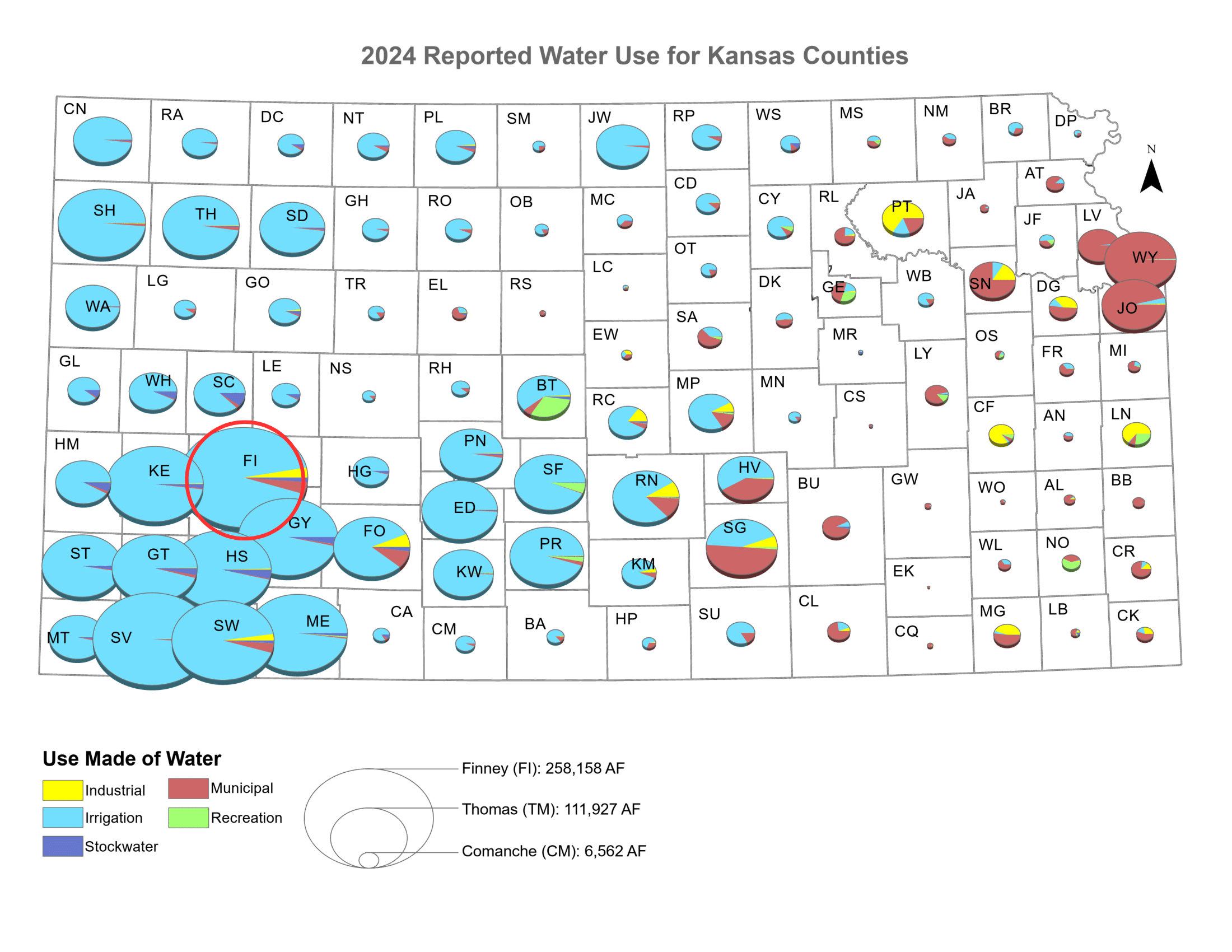

The result of this heavy dependence on the Ogallala for irrigation? Data from wells and sensitive satellite measurements confirm that the Ogallala’s water levels have dropped by about half since the aquifer was first tapped. The decline is especially severe in southwestern Kansas. Finney and neighboring counties’ water tables are dropping as much as two feet per year. And yet, Finney County remains the greatest water user among the state’s 105 counties.

Researchers at Kansas State University determined that about 70 percent of the aquifer in Kansas will be depleted in less than 40 years. Finney County thus finds itself in peril due to years of inattention to the trajectory of aquifer exhaustion. Having taken millennia to form, the Ogallala’s groundwater should be regarded as a finite resource. But as with so many other ecological limits ignored by society, so too has the Ogallala’s capacity. Depletion of the Ogallala and Finney County’s inaction are a tragic microcosm of society’s failure to reckon with planetary boundaries.

Wetlands at Risk

Wetlands rely on local streams that are fed by groundwater springs. Heavy extraction by Finney and other counties lowers the groundwater table, diminishing the springs and ultimately the wetlands they feed. Historically, Kansas had nearly 850,000 acres of wetlands, now reduced by half.

Cheyenne Bottoms, a globally significant wetland serving as a key stopover for migratory birds. (Ken Lund, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The remaining wetlands are nonetheless critical stopover habitats for migrating birds in the North American Central Flyway. In an interview for the Steady State Herald, Dr. Jackie Augustine, Executive Director of Audubon of Kansas, described Kansas’s wetlands as essential for “the survival of numerous bird species, including the endangered whooping crane (numbering only 830 individuals) and millions of waterfowl.”

Wetlands also serve to recharge aquifers. A wetland acts like a sponge that slowly releases water, which percolates through sediments and into permeable rock. In contrast, very little of the water used for agriculture ends up back in the aquifer. Current irrigation practices result in water loss by evaporation. Crop plants take up most of the remaining irrigation water and transpire it into the air. “Evapotranspiration” is the name for this aquifer-depleting combination.

“Local agriculture has a huge impact on the health of wetlands, such as Cheyenne Bottoms Wildlife Area and the Quivira National Wildlife Refuge in central Kansas,” Augustine says.

A Half Century of Forewarning and Inaction

Warnings of the Ogallala’s depletion extend back nearly 100 years, commencing soon after large-scale irrigation. A study done in the 1970s revealed water-table declines and a warning that the area would eventually face a crisis. Farmers experience this depletion firsthand, as they must drill ever deeper to maintain their water supply. Yet state and local officials have done little to respond. Any actions taken to reduce water extraction have been voluntary, not mandated by governments.

Finney County is no exception. Its Comprehensive Plan, adopted in 2018, hints at the scale of the problem, but its recommendations are sparse. It advocates for the development of a “long-range Water Transportation and Water Conservation plan.” Seven years later, this has yet to occur. Perhaps as an acknowledgement that the county’s policies will not stave off aquifer depletion, “water transfers from east to west” is the last strategy listed in the plan. “Water transfers” entail transporting water from the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers to replenish the local water table.

Advocates for this approach include Mark Rude, the 23-year Director of the Southwest Kansas Groundwater Management District 3, one of five such districts managed by the state of Kansas. District 3 has been criticized as having too lax a response to the impending crisis. Critics note, for instance, that up to 87 percent of the district’s spending has gone not to conservation efforts, but to salaries, travel, and other personnel expenses.

District 3 sought to demonstrate the feasibility of long-distance water transfer. It spent $7,000 to transport 6,000 gallons of water 400 miles by truck. The water was poured into the sandy, dry bed of the Arkansas River in Finney County. It receded into the sand in seconds and added to the aquifer the equivalent of just a few minutes of extraction from a single well.

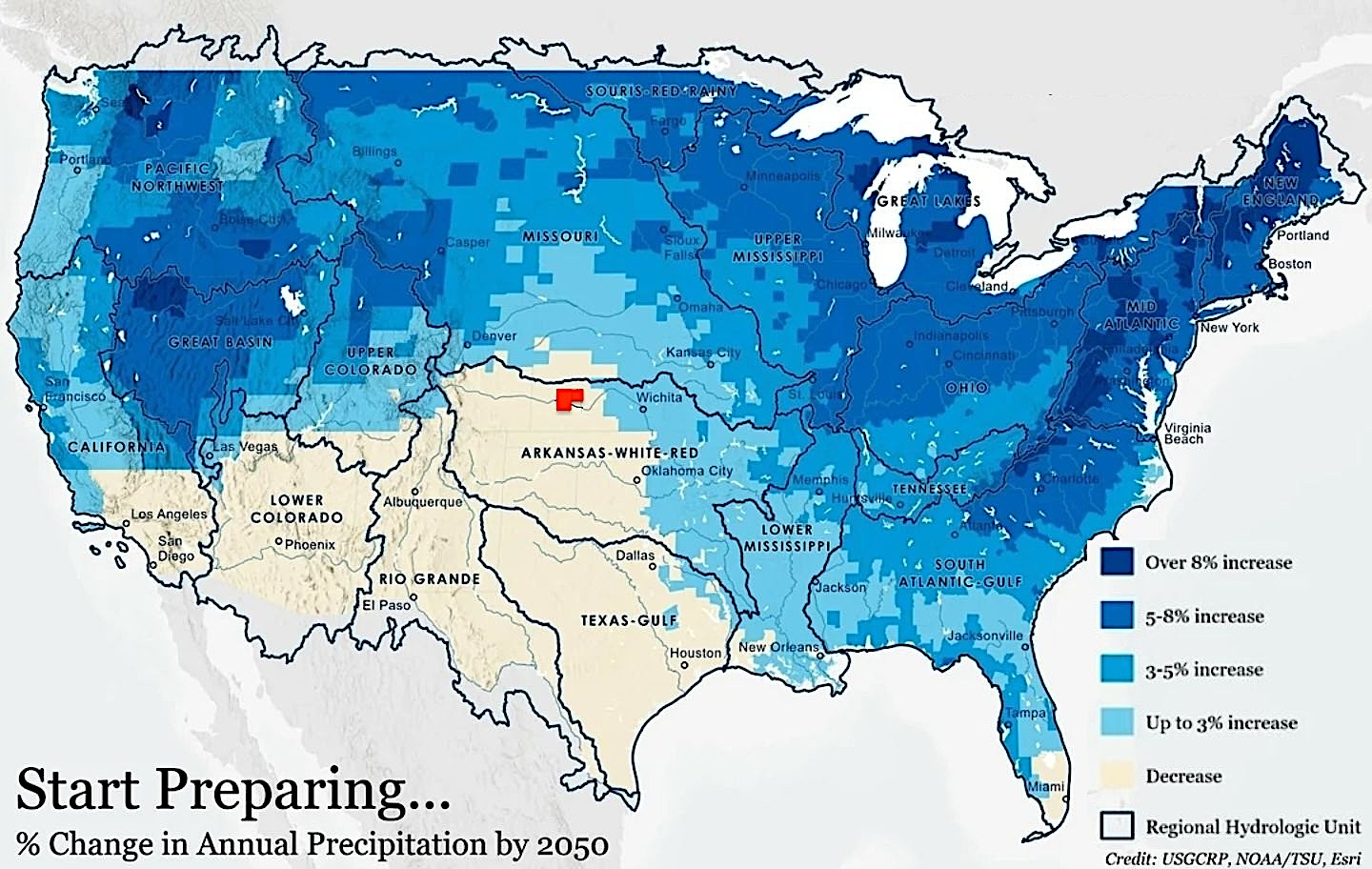

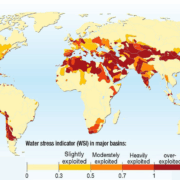

Climate models predict drier conditions in the coming decades for southwest Kansas. Finney County is highlighted in red. (U.S. Global Climate Research Program, Public Domain)

Another of District 3’s proposals involves pumping Missouri River water thousands of feet uphill, using an aqueduct to transfer it to western Kansas. The cost estimate included over $18 billion for aqueduct construction and $1 billion for yearly maintenance and operation.

More extreme “water transfer” proposals may emerge as depletion accelerates. NOAA predicts warmer temperatures with less rainfall for southwestern Kansas. Warmer temperatures require more water for crops. This past July, the governor declared a drought emergency for 13 counties, including Finney. Recent droughts are likely a harbinger for increasing numbers and severity in the future.

Yet Finney County carries on with business as usual. Its Comprehensive Plan includes goals to dedicate more land to municipal and industrial growth. Finney County is not alone. Policymakers and farmers throughout the region fail to address the root cause of groundwater depletion: an economy too big for its aquifer.

Buying Time

Producers in other regions of Kansas have taken depletion warnings to heart, deploying a number of efficiency strategies to reduce their water consumption. One strategy is to switch to crops that are drought-tolerant and consume comparatively low amounts of water. Corn accounts for about 50 percent of the acres under irrigation in western Kansas. Growing sorghum instead of corn, winter rye and oats instead of wheat, and millet instead of soybeans could feasibly save 12 percent of agricultural water use by 2050.

Water use by Kansas county in 2024, with Finney County water use circled in red. (Modified from Kansas Department of Agriculture)

Farmers could further reduce extraction by phasing out grossly inefficient spray irrigation methods, which cause substantial quantities of water to simply evaporate. Sub-surface drip irrigation has the potential to save up to 35 percent of the water used in crop growing.

While these water-saving measures are eminently judicious, it is sobering to recognize that if universally deployed, they may only buy the region a few more decades of agricultural production. It would take 6,000 years to recharge the Ogallala in its entirety, if rainfall in the watershed were devoted to such purposes. With business as usual, 70 percent of the aquifer will be depleted by 2060. These dire truths demonstrate that—as long as the economy continues to grow—efficiency measures will only delay the inevitable.

Still, buying time is important for transition planning and to avoid catastrophic ecological costs that extend far beyond Kansas. Important ecological systems depend on the Ogallala, and their protection depends on a step-wise downscaling of water extraction into alignment with natural hydrological cycles.

Long-Needed State Action

While Finney County has done little to address an impending water crisis, some communities have stepped up to recognize water limits. The City of Hays in the west-central part of the state has taken steps to limit water use with tough regulations. They have a water-conservation plan and are purchasing water rights from area farmers to safeguard their municipal supply. Augustine describes Hays as a model for taking groundwater depletion seriously.

The Kansas State Senate in recent session. (Kansas Legislature, Public Domain)

Other communities may have no choice but to follow in Hays’s footsteps. After decades of inaction, the state has finally moved to force local action. In 2025, the governor signed a bill creating a task force dedicated to analysis of water use, policy, and funding statewide.

Prior to this bill, many regarded state regulation as inadequate and even as incentivizing greater water extraction. But the tide may be turning, as the state’s new plan focuses on future supply with a goal to “conserve and extend” the Ogallala. The new bill requires the task force to: “Evaluate major risks to the quality and quantity of the state’s water supply, including any impact on current and future economic growth and population stability.”

A realistic assessment would conclude that water will limit economic growth and that the state should plan accordingly. The political pressure to soften this conclusion is enormous, but the stark reality is that the Ogallala isn’t growing; it is receding. Living within groundwater limits is part of living with limits to growth, an inevitability that can’t be ignored much longer.

The Way Forward: Living within Limits

Kansas State University sociologist Dr. Matthew Sanderson and his colleagues conducted a 2018 survey of the attitudes and perceptions of the producers (farmers) operating above the Ogallala. In an interview for the Herald, Sanderson noted that the state has a plentitude of agencies and organizations involved in water management and conservation, but their guidelines tend to emphasize voluntary efforts.

The Ogallala Aquifer and its decline as of 2023. (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Public Domain)

This can create a tragedy of the commons in which water users find it tempting to take advantage of any conservation performed by others. Sure enough, 93 percent of the surveyed producers are not involved in organizing group conservation efforts.

However, producers do recognize the tragedy. According to Sanderson, “A vocal minority advocates for water being used without regulation. But our research indicates that about 85 percent of respondents—and these are producers—say that groundwater depletion is a severe problem.” Moreover, over 92 percent of surveyed producers feel groundwater should be conserved, and half say water regulations aren’t strict enough.

Sanderson feels that these opinions are even more prevalent among the general public. He sees great potential for extending the life of the aquifer through cultural change and public policy. He is working with an interdisciplinary team of scientists on a project that investigates the possibility of a “Q-stable analysis” to project the aquifer’s regenerative limits. The analysis would indicate the rate at which each producer could withdraw from the reservoir to yield a stable water level.

Tragedy Writ Large

The Western Arkansas River in Finney County is now a dusty tract used by ATVs for most of the year. (National Weather Service, Public Domain)

Like the Ogallala’s, Earth’s limits are real and non-negotiable. And just as Finney County has ignored water limits, the world has ignored the limits to Earth’s biophysical resources, with only the rarest exceptions (such as protecting critical habitat pursuant to the Endangered Species Act).

The standard “solution” to local limits is importing resources, or “biocapacity,” from areas still able to export theirs. Finney County’s water transfer proposals are a classic example. Meanwhile, mainstream policymakers and producers advocate for efficiency gains and a transition to renewable energy.

But until we recognize the disconnect between Earth’s limits and the economic growth imperative, reckonings like the one facing Finney County will become more common. Will we learn from them—and keep our counties great—before a collective crisis ensues?

Dave Rollo is a policy specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

Dave Rollo is a policy specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

My mom grew up one of eight siblings on a Dust Bowl farm in Meade County, KS. Uncles began putting in irrigation circles by the ’70s, I think. Crooked Creek, a fairly goodsized creek has dried up. The family got through the Depression and five years “without a crop” in the ’30s, as my uncle put it, because they lived in an artesian valley where water bubbled up from a pipe stuck in the ground. Now the artesian water is gone. There are some water use regulations (spacing of wells, etc) but the Ogallala is not being managed for the long run, especially if rainfall decreases.

In 2016 I stopped on Interstate 70 to talk to a farmer attending a pivot irrigation system. He indicated he had sold his previous farm because the level of the Ogallala had dropped 65′ requiring extensive well work and a future that was dim. He bought his current farm, which had better lateral transport but had observed a 6′ drop there. Thirsty corn, replacing less demanding wheat and milo, is a big part of the problem. Thanks for addressing this issue.

BTW corn subsidies and the use of corn for fuel has also returned acreage once restored to tall grass prairie under environmental support programs, to corn as the prices for corn escalated with demand. Farmers found the restoration program attractive on land that had lower yields for corn. The high prices, however, reduced this attraction and many acres were plowed under and returned to corn.

Thank you, Dave Rollo, for this superb and sobering overview about depletion of the Ogallala Aquifer. The focus on one representative microcosm, Finney County, Kansas, makes the tragedies all the more tangible. That place is experiencing particularly severe episodes of looming problems for agriculture and municipalities, dangers for wildlife, and family dreams dried up as Max Kummerow reports in the Comments about nearby Meade County. So much loss of so much water brings potential for wholesale degradation of both the ecosystem and the economy. Life in Kansas won’t be like Kansas anymore. And no Wizard from Oz or with technological innovations can create more water.

Still, the essay does point to some innovations with impressive mitigation efforts, which are buying time for dealing with the problems. These are not solutions, since the complex problems are rooted in some simple math, with so many demands on the finite resource. The aquifer is vast but current depletion is leading to 70 percent of its water gone in the next 35 years. The complexities with aquifer and with mitigations are treated more seriously in proportion to the overlooking of simple facts.

The essay concludes that only limits on economic growth offer hope. Less growth can also reduce incentives to bypass environmental support programs such as those for prairie grasses, as Jay Jones points out in the Comments. Fear about less economic growth is motivating continued use of the Ogallala’s water, but ironically, ignoring its problems also adds to the hemmed-in growth that that the water use is attempting to avoid. Either way, as this stark account shows, economic growth is going to be curtailed. Overlooking the simple math of depletion will make the losses still more difficult, but addressing those realities offers hope for better working relations with natural facts.

Dave Rollo refers to sociologist Matthew Sanderson who has found hope in discovering that the vast majority of even those using the water is already hoping for conservation—92%, a number that would make any politician envious—and half of those say of current regulations that they “aren’t strict enough.” The sentiments in Sanderson’s data are significant first steps, but they are not enough for taking action because so many people are surrounded by the routines of economic growth. Even as they feel its dangers and sense the importance of change, they are constrained by cultural habits. How then to persuade the people holding those sentiments to break with those traditions?

An effective next step would be a version of Good Cop-Bad Cop. Conservation of water can appeal by associating it with the wonders of reduced growth, from visions of wildflowers on lawns and wildlife in prairie parks, to shared rides to school and work, more time with friends and family and on foot and on bicycles, less traffic on the roads, more good food requiring less water, and more ideas that readers of this page can provide as resources to make change more attractive and possible. Yes, more exercise will make people thirstier! But the water use in response will pale compared to mega-use of water on farms and in cities. Let the good in those steps sink in, or the “bad cop” will bring the wordless argument of a glorious resource gone dry. The good possibilities will persuade many; the bad prospects will change still more minds and hearts; together they can build a majority for the cultural change to prod for policy change. The path of persuasion brings no guarantees, but it can provide an important supplement to reports of conditions bleak and getting worse.