City Limits in the Hoosier State (Keeping Monroe County Great)

by Dave Rollo

Monroe County, Indiana, just west of the Bloomington municipal boundary. (CASSE)

Monroe County, Indiana, lies just an hour south of the state capital (Indianapolis), yet it retains a rural character. The gently rolling hills and farmland of the Mitchell Plain characterize the central and western portions of the county. Porous limestone bedrock (known as karst) imposed limits on municipal water resources until the late 20th century, when the Army Corps of Engineers created Monroe Reservoir.

East of Mitchell Plain lies a forested landscape of hills and “hollers” (valleys). Its beauty has long attracted landscape artists, including TC Steele, an impressionist of some fame post-Civil War. Steep slopes and federal and state forests have protected much of eastern Monroe County from development. Perhaps reflecting this history of scarce water resources and natural beauty, the county has a strong conservation ethic, which is evident in its comprehensive plan.

The county seat of Bloomington, located in the center of Monroe County, is home to Indiana University. The campus is renowned for its beauty, with historic, local, limestone-clad buildings set within woodlands and open green spaces. Bloomington contains six percent of Monroe County’s land area, yet its 80,000 residents make up 60 percent of the county’s population. More than half of Bloomington’s residents are students, so the city’s population fluctuates seasonally.

After Bloomington’s population doubled from the 1960s to the early 2000s, both the city’s and county’s populations have plateaued in the past two decades. Monroe County’s population has even declined slightly in recent years. Despite the steady-state advantages of these stabilized population trends, Bloomington’s past two mayoral administrations have viewed city expansion as an imperative.

Annexation is the means of expanding the city, placing adjacent land under city control and taxation. In Monroe County, this process is in its eighth year of contentious debate and litigation. Despite considerable efforts by the city government and growth advocates, county residents have held city expansion at bay. Now, a pending decision by the Indiana State Supreme Court may set a new standard limiting the growth of Hoosier cities.

“Right-Sizing” Starts on the Wrong Foot

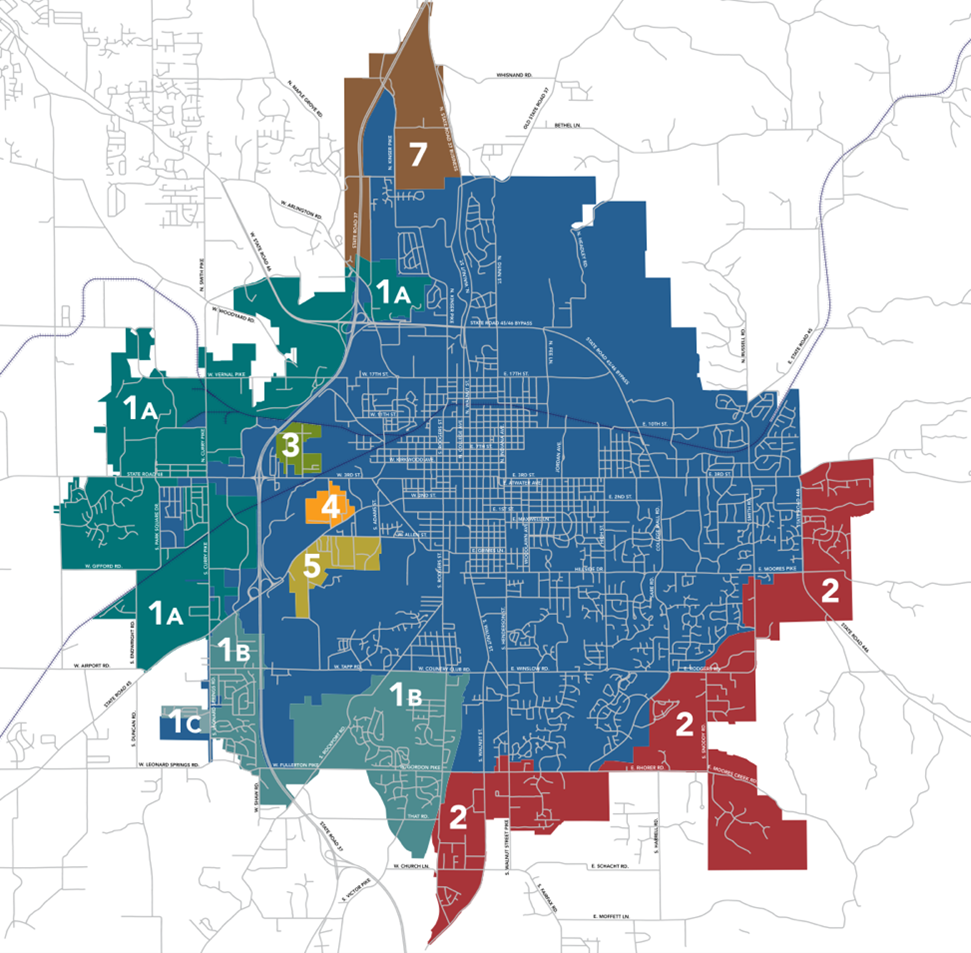

In the past, Bloomington annexations involved only small parcels of land. Therefore, when Mayor John Hamilton put forward an ambitious proposal in 2017, there was immediate blowback. The plan would add over 14,000 Bloomington residents and increase the city’s area by almost a third. Proponents invoked a need to “right-size” the city, suggesting that Bloomington would remain deficient and second-rate without growth.

City of Bloomington, Indiana (blue), and the seven disputed areas for annexation proposed in 2017. (City of Bloomington)

All three Monroe County commissioners, alongside their constituents, opposed the plan. They were concerned that tax increases would affect the cost of living and that annexation would irrevocably change the county’s rural character. The mayor countered by portraying county residents as freeloaders—enjoying the urban and cultural benefits of the city without paying their share.

The county-city division became heated. County commissioners reproached the mayor for not consulting them about county lands they would lose jurisdiction of.

Some Bloomington City Council members echoed this assertion. In an interview for the Steady State Herald, former city council member Susan Sandberg recounted, “Pushing forward while excluding our county colleagues was the first of several mis-steps by the mayor and created a united front of county residents and their elected representatives.” The rift created distrust that affected cooperation thenceforth.

Substantial public outrage elicited intervention by the state. In April 2017, Indiana Governor Holcomb signed a bill that obstructed the annexation. Mayor Hamilton’s administration challenged the intervention in a suit against the state. In 2020, the Indiana Supreme Court ruled that Bloomington could continue the annexation process. By then, however, county residents had organized in opposition and gleaned considerable support from the Indiana General Assembly.

Remonstration Campaign

County Residents Against Annexation launched a door-to-door campaign to resist involuntary annexation. (CRAA)

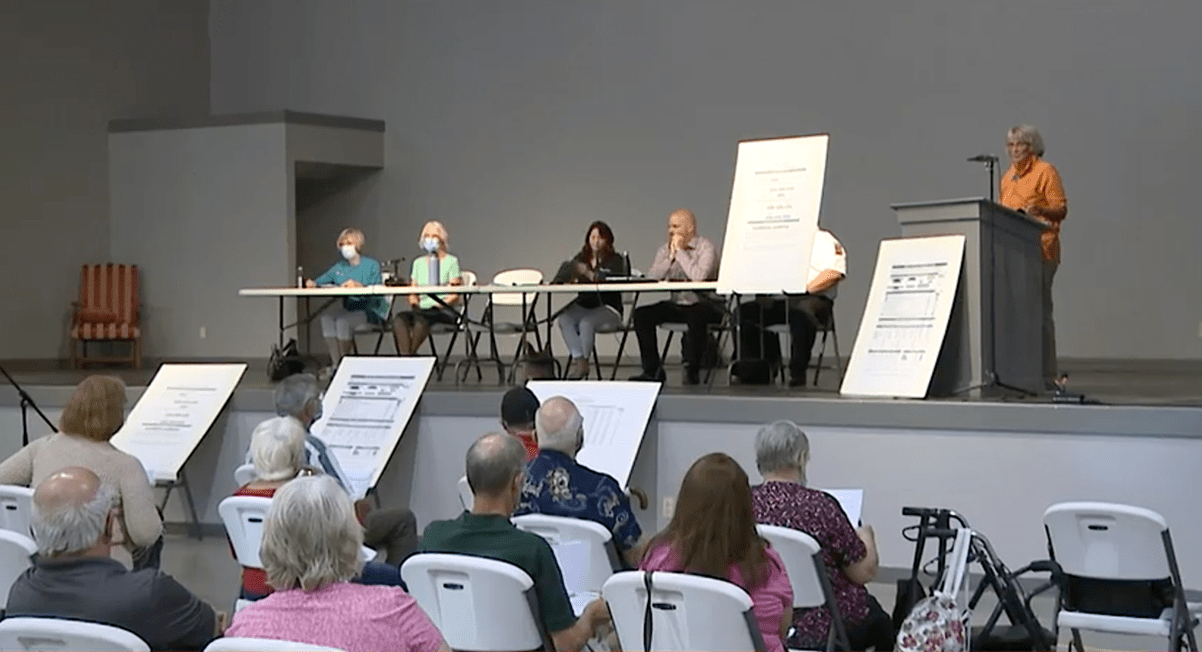

The annexation ordinances were brought before the city council in September 2021. Public comment during the deliberations weighed heavily in opposition of the ordinances. Referring to the city’s heavy-handed approach and the resulting rage amongst county residents, county commissioner Julie Thomas stated portentously, “You are setting this up for a lawsuit…”

Despite this warning, the city council approved the legislation with a 6-3 vote. Affected county residents had 90 days to sign “remonstrances,” or formal objections. The number of signatures would determine, under Indiana law, whether the annexation could proceed. If 51 percent of residents in an area up for annexation signed remonstrances, they could challenge Bloomington in court. If 65 percent signed, the annexation of that area would be automatically invalidated.

By this point, citizens had already formed County Residents Against Annexation (CRAA) to gather signatures and hire legal counsel. Organizers canvassed and visited neighborhood meetings to raise awareness, in hopes of clearing the remonstrance bar.

A Case for Concurrency

There is a constitutional question of whether Bloomington has the right to bring peripheral land into the city’s jurisdiction. However, rights aren’t the only issue at play. Several city councilmembers have raised concerns about the city’s ability to expand its infrastructure by one-third while serving existing residents.

Andy Ruff has served on Bloomington’s city council for 22 years. (Monroe County Public Library Cable Access Television – CATS)

When municipal infrastructure (roads, sewers, water systems, etc.) and services (public safety, sanitation, etc.) are deficient, many believe new tax revenues from annexation can fill the gap. However, the new land and residents often require more services, exacerbating the deficiency. Before extending its boundaries, a city should ensure that public services and infrastructure are “concurrent” with any new development proposals. Many would say Bloomington doesn’t meet this standard.

The Public Works Department’s policy states that streets will be repaved every 20 years, yet many streets have been waiting for over 40. Sidewalks and stormwater infrastructure remain absent or inadequate in many neighborhoods. City services have likewise failed to keep pace with expansion. For example, City-commissioned consultants recommended 105 police officers, yet the Bloomington Police Department has only 80 sworn officers. It would need 130 to properly police the city if the annexation were successful.

This is a longtime concern of city council representative Andy Ruff. In an interview for the Steady State Herald, he noted that growth has rarely paid for itself, instead resulting in higher service fees and taxes:

“We’re constantly told by the advocates for growth that it always gives benefits, but never costs. And, many of these costs are hidden—more congestion, more crime, more pollution. At the very least, city infrastructure and services should follow a policy of concurrency—that is, are we at least keeping pace with our needs, or are we told to grow in order to play catch-up, where our needs are always out of reach? We are still catching up with past growth.”

When campaigning in 2023, councilmember Ruff noticed that citizens shared these concerns: “Threats to quality of life were a constant refrain that I heard among city residents. City residents had been paying higher utility rates for water utility expansion as well as increased property and income taxes and yet were experiencing the downside of growth in reduced livability of their community.”

Brakes on Expansion

Ruff succeeded in his run for city council in 2023. The election also brought a new mayor to office, as John Hamilton declined to run again. During Mayor Kerry Thomson’s campaign, she promised to improve city relations with the county. Nevertheless, she continued litigation against the county government and residents when it came to annexation. To date, this litigation has cost taxpayers over $2.4 million (plaintiff fee reimbursement has yet to be determined).

One of the city’s key arguments in court relies on “remonstration waivers.” Some county residents signed waivers in exchange for city sewer connections. In effect, they waived their right to challenge annexation.

Northern suburbs of Indianapolis. Suburban sprawl has replaced many of Indiana’s rural areas. (Carol Highsmith, Picryl)

However, in 2019, the Indiana General Assembly enacted HB 1427, which voided waivers more than fifteen years old. This restored the right of remonstration for many affected county residents. Multiple legal challenges ensued. In June 2024, a special judge ruled against the City on constitutional grounds. In August 2024, the judge also found that Bloomington failed to meet the statutory requirements for annexation, which involve demonstrating the city’s need for the annexed areas.

Mayor Thomson immediately declared her intent to appeal the decision, taking the case to a three-judge panel of the Indiana Court of Appeals. The CRAA objected, asserting that the City of Bloomington meant for the appeals process to exhaust their resources with litigation expenses.

In February 2025, the appeals court decided in favor of the state legislature and the CRAA, ruling against Bloomington’s attempted annexation. The unanimous decision found that “Bloomington lacks enforceable rights to challenge the 2019 Act under the Federal and Indiana Contract Clauses.” Despite this significant loss, the city administration has made a final appeal to the Indiana State Supreme Court. A decision is pending.

Precedent Setting?

Both Bloomington mayors have argued that growth—and the need to extend municipal services—is inevitable. They point to parts of the areas proposed for annexation that are already “urbanized,” with density and commercial activity similar to that found within the city’s borders. However, a significant portion of these areas remains low-density and rural in nature.

Steady staters argue that a final decision against Bloomington would set a precedent preventing other Indiana cities from expanding recklessly. Indiana is one of the few states that permit “involuntary annexation.” This means that a city can annex an area even if a majority of landowners have filed remonstrances, as long as the city can demonstrate it is in the best interest of the community to be annexed.

Monroe County has shown its intention to maintain the county’s rural nature and low density. County residents and commissioners want to keep the county great, protected from economic bloating. County commissioners have voted to downzone (reduce zoning density) some areas. County Commissioner Lee Jones—a supporter of the rezone—spoke against calls for growth from a commissioner colleague and growth advocates, such as the Bloomington Chamber of Commerce. “There is no such thing as sustainable growth,” she declared.

A public meeting on the Bloomington annexation plan, held by Monroe County officials. (Monroe County Public Library Cable Access Television – CATS)

Commissioner Jones’ comment echoes a steady-state ethic found in Bloomington’s own comprehensive plan. The plan’s executive summary states, “Our community has resolved to do our share to protect the biosphere, and critical to this protection is recognizing that infinite growth is neither possible nor desirable in a finite world.” It adds, “Measures of quality of life based on equity, human fulfillment, and community resilience should replace inadequate progress measures based on aggregate growth in conversion of our natural world to built capital, and corresponding increases in resources and energy.”

With a final decision by the highest court in Indiana just months away, a state-wide precedent for city limits may well be the outcome of this local battle. In Monroe County, a decision against expanding Bloomington would be a costly disappointment for growth advocates. However, it would align the city with the aspirations laid out in its comprehensive plan, toward a steady-state future.

Disclosure: The author serves on the Bloomington City Council and was one of three councilmembers who voted against annexation.

Dave Rollo is a policy specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

Dave Rollo is a policy specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

Municipalities and elected officials continue to place the economy first along with departmental needs and wants over that of resident’s financial stability and capabilities. “Affordable housing” is another ruse when decision making, and actions are creating unaffordable living conditions for many. TIFs, business emphasis and promotions, overrides and overspending with no real tax relief has put most households into financial hardship and stress. The fact that the majority of funds and consumer purchase power comes from and relies on resident financial means is loss or ignored. Without limits on growth and population numbers as well as spending caps we cannot achieve a steady state economy. Officials don’t seem inclined to level the playing field and create a community operating on a level funding and services budget.

I’m curious what the arrangement is with respect to public schools. How are they districted? How are taxes for the school districts distributed and collected? What is the relative equity of the city schools vs. schools beyond city limits? Where I live, the school tax far, far exceeds the municipal or the county taxes. I wonder if it’s different in other parts of the US. If annexation were to proceed, what would happen to the school districts involved, to the individual schools, and to the students and their parents?