What Makes a County Great?

by Dave Rollo

Think about the county where you live. Picture your favorite streets, event spaces, scenery, or terrain. If you’ve lived there awhile, chances are you know what makes it great: the natural, cultural, and commercial places whose characteristics make your community special to you and your neighbors.

Your connection to them becomes part of your sense of place. You delight in taking visiting family and friends to these special sites and you lament changes that threaten or despoil them. Because you value these settings, you hope those in local office appreciate them, too, and are working to maintain, protect, and enhance them—or at least to do them no harm.

Development patterns reveal a community’s priorities. (Alfred Twu, Wikimedia)

As the Policy Specialist for CASSE’s “Keep Our Counties Great” campaign, my interest in communities begins with fundamental questions about places and the policies that impact them. Do the guiding documents of the community reflect the value of conserving our special places? Or do our government representatives and county planners undervalue such places, relying primarily on economic and spatial growth to measure the quality of life?

An at-a-glance look at many counties reveals that most planning documents do not question the benefits of economic growth. Indeed, in many communities, GDP is the primary measure of progress. Many officials and citizens assume that bigger is better, or at least that a growing GDP benefits everyone. Yet ample evidence suggests that this is not the case.

Clearly, local policy is misguided if it compromises quality of life while pursuing “progress.” In many counties, decades of sprawling development separated residential and commercial activities, necessitating car travel. The result is a monotonous expanse of built artifacts that reduce social and community interaction and connection. Sprawl around metropolitan areas has also supplanted many acres of valuable farmland, fields, and forest.

How might county leaders recognize such a mismeasure of community good in their planning processes and documents? How might they avoid mistakenly assuming that they are adding to community well-being when all too often they are degrading our special places? To answer these questions, it is helpful to apply the conceptual framework of sustainability to county planning.

Thinking in a Sustainability Framework

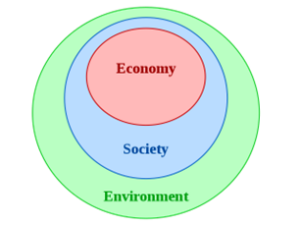

By definition, sustainability takes the long view, emphasizing a harmonious balance among social, economic, and environmental domains. Since humans and our artifacts and institutions, including our economy, depend ultimately on solar input and a host of ecological services, the balance among the economy, society, and the environment can be pictured as a nested model in which human habitation and activities are a subset of nature.

Fundamental to the nested model is the implication that there are limits to the operational space of each domain and that an appropriate scale of society and economy relative to the environment can be found. Indeed, the increasingly referenced planetary boundaries concept could be applied similarly at the local level to identify ecological limits that a community has passed, or is about to pass.

Nested dependencies model of sustainability (K. Tucker, Wikimedia)

And although counties can be “open systems” that allow for human migration and the import and export of goods, societal and economic growth that is out of scale relative to the local environment degrades our sense of place and quality of life. Living sustainably often means living locally, with fewer imports and less reliance on the carrying capacity of other communities. (If every county outsources its environmental needs, our collective planetary health and survival are necessarily threatened.) Living locally brings us into immediate relationship with the nested dependency of our local—county—environment. And because supply chains are often fragile, less reliance on imports (aka import substitution) builds resilience for vital needs such as food.

The scale of human activity depends to some degree on the capacity of the natural environment to provide for us and on how lightly we occupy nature’s envelope. Recognizing this provides a foundation for exploring the conditions of optimizing and preserving our sense of place.

Reflecting further on the nested model of sustainability, it is evident that the social, economic, and environmental domains are porous, and that they overlap in many ways. The ways in which these domains interrelate and complement each other provide many reinforcing opportunities for optimizing our sense of place.

Attributes of Greatness: Living Locally

In keeping with the nested model of sustainability, great counties recognize human dependence on nature’s services, so such services should appear prominently in county approaches to community planning.

For example, every community requires water for its survival, but water resources are often degraded by human impacts such as point source pollution, erosion, and contamination by runoff. These effects can be alleviated by wetland preservation, whose value is often woefully underappreciated. Globally, wetlands are estimated to contribute $47 trillion in services to economies. So an appreciation of wetlands and of the importance of maintaining the water quality of our local lakes, rivers, and reservoirs becomes critical for planners. Knowing the sources of county water and of the natural and mechanical means for purifying it is likewise important.

Food provision is another critical service of nature. Sadly, most farms pursue an industrial model of productivity that is damaging to land and biodiversity, and whose benefits are short-term—typically a single harvest—before massive amounts of new fertilizer and other inputs are required.

Great counties with a deep sense of place have diverse local economies that residents recognize and support, seeking to substitute for imports whenever possible. Fortunately, many communities are finding that local food production from regenerative, organic farms is economically viable, provides an important component to local economies, and promotes community gatherings at farmer’s markets. Regenerative organic farms are far more complex in biodiversity, build soil instead of depleting it, retain runoff, and obviate the need for much of the liquid fuel used to transport food to communities.

Local food production creates and maintains a sense of place. A trip to the farmer’s market provides a bounty of fresh food; connections with the community; cultural enrichment, as with entertainment by local musicians; and the deep satisfaction of supporting a farmer-neighbor who provides sustenance to the community.

Olympia, WA Farmers’ Market (Wikimedia)

Local farms often generate spin-off businesses that convert farm output to value-added products, from meals at local restaurants to cheese, beer, baked goods, and other products. “Foodie” communities are becoming widespread, featuring farm-to-table restaurants, you-pick orchards, and varieties of locally made and sourced products. A network of local-first farms and other businesses recirculates dollars within the community and builds wealth that would otherwise be lost to imports.

Besides clean water and food production, nature provides a myriad of ecosystem services such as air purification, climate regulation, flood control, and many non-material benefits related to psychological, spiritual, and aesthetic wellbeing. The unique species of birds, mammals, insects, trees, and flowers that share our spaces become familiar to us, help us to identify our home place and to feel connected to our world, and give us solace and support, joy, and fascination.

This makes preserving larger tracts of wild space important. Even the human-imposed order of neighborhood parks should reserve areas of wildness, especially for children to explore, learn, and connect with the source of human flourishing.

Because space is limited within a county that protects and preserves its natural attributes, setting limits on the form and scale of human habitation is a vital feature of great counties. For example, increasing the population density of town centers and neighborhoods protects farmland within the county. Town centers, neighborhoods, and neighborhood activity centers also provide small, walkable areas of commerce, minimizing the need for car travel.

Communities with historic architecture are highly valued and many town and city squares are magnets for new investment and a cultural draw for locals and tourists alike. Original plat patterns can serve as templates for new development that respects scale and provides for walkable and bikeable communities in which the density of human habitation serves as an anchor for local retail and commerce.

Preserving and Strengthening Great Counties

Counties can protect and build upon their sense of place—their greatness—by careful planning. The nested model of sustainability establishes the groundwork for planning documents that are aligned with community well-being.

Sustainable communities might look and feel different. (ITDP, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 DEED)

Ideally, a comprehensive plan would encapsulate the natural, historic, and cultural elements of the built environment and optimize the well-being of each. Timescales vary, but a 20-year term is common, with amendment options in 5-year increments. Comprehensive plans strive to be holistic, in contrast to the old “growth policy plans” that focused almost solely on expanding the built footprint and GDP. Because social, cultural, and economic activities must fit within the supporting natural environment, a focus on aggregate growth harms and diminishes the natural services on which communities depend.

Comprehensive plans, then, would aspire to embrace qualitative development. To ensure that communities achieve a sense of place and human scale, and that the natural envelope is protected, the process for creating comprehensive plans should invite all stakeholders to participate to ensure that perspectives outside the narrow growth paradigm are included. Historic protection groups, conservation organizations, neighborhood representatives, local business owners, and other advocates for community welfare should have a place at the table.

Good models of sustainable communities already exist. For example, the City of Bloomington, Indiana, has a plan that addresses

“…not merely the physical growth of our community, but recognizes the variety of human and natural systems interactions necessary to achieve a sustainable community with a high quality of life for our residents.

We acknowledge that healthy natural systems are the foundation for flourishing human societies. Globally, the scale of human impact is undermining this foundation, and we must reverse the course of environmental degradation to ensure a livable future. Our community has resolved to do our share to protect the biosphere, and critical to this protection is recognizing that infinite growth is neither possible nor desirable in a finite world.

To track our community’s progress toward greater sustainability and resilience, we require measures of success that are inclusive of environmental, social, and economic well-being. Measures of quality of life based on equity, human fulfillment, and community resilience should replace inadequate progress measures based on aggregate growth in conversion of our natural world to built capital, and corresponding increases in resources and energy.”

Here at CASSE, our mission includes working on the local scale to advance a steady state economy. An important goal of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign is to survey all counties in the U.S. and Canada and find models of comprehensive plans that preserve their community’s sense of place, respect limits, and optimize the functioning of the environment, societal, and economic domains. By drawing on these models and their successes we hope to provide a guide for counties to follow.

Dave Rollo is a Policy Specialist at CASSE.

At first I thought your motto was a typo of the phrase “What makes a country great?” But now I can that this a good idea, because it is something people can related to and act on. It makes me want to check out my county’s land use code, and see how these ideas might relate to it. Thanks!

Hi Rick. Yes, you may wish to check your city or county land use and development policies at their respective planning departments. Hopefully, your local government has comprehensive plan, and it provides aspirational directives for code to follow. The rubber hits the road with the development codes adopted by your legislative authority, e.g., your town, county or city councils. Needless to say, it is often a struggle for communities to live up to their aspirations, but having a vision is half the battle.

Good day

Just a thought…What does the word tourism in the article conjure up?

Perhaps travel and consumption of which we all need to

do less. Monbiot provides some interesting retrospection on

the subject of tourism.Maybe have a look.

The first three paragraphs are certainly pertinent. The rest of

the article is not relevant here.

https://www.monbiot.com/2023/10/04/the-cruel-fantasies-of-well-fed-people/

Good Day, Tim. I’m in agreement with you (and Monbiot) that tourism is problematic, both in our collective impact (~8% of our carbon emissions) and in corroding the best aspects of our valued places. I wasn’t meaning to promote tourism, but to simply say that people will generally find well-planned, vibrant, and architecturally distinct communities as places they enjoy visiting – locally or from abroad. Perhaps tourism on a local to regional scale is an appropriate step to limit our impacts. Thank you for weighing in!

Even among steady staters there may be differences of opinion on Dave Rollo’s reference that increasing population density of town centers and neighborhoods protects farmland within a county, and by inference, sense of place. Show me a tee-shirt that says DENSITY and I will wear it; I witness in my own daily life how density (a) has improved non-motorized mobility and sense of place (our city of Clichy could be called a “5-minute city”) and (b) has helped to preserve low-intensive farmlands and wild areas within the group of counties (“departments”) that comprise our region. Two daughters of mine live in unwalkable sprawl-impaired California cities that do not even have downtowns. Improving sense of place at the county level will reduce a growth-oriented aberration: people from unwalkable communities flying 8,000 miles to dense European cities … to take a walk.

Thanks, Mark for sharing your support of density. Density serves a number of purposes, such as making local commercial and retail enterprises viable, achieving numbers of bus ridership to maintain public transportation, creating walkable and bikeable environments, and providing space for nature and farms. The goal of us steady-staters is to reduce our individual and collective footprint to respect carrying capacity, and sprawl is antithetical to that aim.

This piece is timely. Just today I learned that Portland, OR is planning to roll back years of hard fought-for progressive environmental regs to accommodate housing development. Profit is the

driver,…expediency is the justifier. I plan to object at the public meeting on Oct 24th.

Hi Leslie, Sorry to hear about the proposed reversal of policies. Best of luck representing a sustainable approach. In my experience, active residents showing up is the antidote to the development interest-driven process.

Good article! My little college-town borough of roughly 6000, roughly 2000 households, is working on a comprehensive plan. It was motivated by the findings of an affordability task force. All sounds good, right? It would be, if the borough would be transparent about the comprehensive plan, and allow for citizens to provide input to the consultant they hired to do it.

The affordability task force formed in response to a permit request by a developer to build a 5 story condo complex in the heart of the tiny downtown, with units starting at $1M. Next to the two-story buildings along that block, this 5-story construction would tower like a monster. It also is two lots wide, and involves demolition of two buildings. Both those buildings are old, but in good shape. One is historic, the other is evocative of a bygone era. After much back and forth, the developer found a way to preserve the front half of the historic building and attach it to the complex. Since the code allowed it, the developer got the permit. Increasing density is a good idea, but you sure have to be careful how you define what’s permitted.

Dave, you bring up the permeability of the nested system. I’d like to see a follow-up article on how to limit growth in the face of increasing migration. New York City is considering suspending its right to shelter law now that shelters are strained to their limits. As climate change, organized crime, and kleptocracies trigger more migration, how are the migrants to be treated with justice and humanity? What can overwhelmed counties and municipalities do?

Hello Robin, I’m distressed that the consultant’s plan did not involve resident input.

I too have observed occasions when the “experts” drive through plans without meaningful collaboration with citizens. Besides the historic nature of the buildings you describe, there is the embodied energy within them in their construction. Retrofitting existing structures is the more sustainable path.

There is a tension between increasing density and preservation, of course. The right balance is often found in preserving notable structures, and through infill of brownfields, parking lots, and substandard structures. Creating too many apartment buildings abets rent traps, where people cannot build equity by owning. A mix of housing is an important component in the goal of creating a sustainable community.

Overpopulation and migration are important matters for sustainable communities to address – and would be important topics for future articles. They are complex in that they involve concerns about justice, politics, cultural considerations, and much more. On a national level, we should be addressing the root cause and the drivers of migration (e.g., migrants fleeing exploitation or repression in their country of origin). It is also increasingly clear that migrants are victims of climate dislocation. Locally, communities can only respond to what immigration policies are pursued nationally. As you note, counties and cities are open systems and migration in and out of them will occur. My focus is on those policies that limit the ecological footprint of communities, and does not preclude (really necessitates) working on state and federal levels

This article provides not only countries, but also individual communities, and their citizens, to adapt to a future that marks ‘The Great Unraveling.’

Hi Shaun. Agreed – the growth economy cannot continue indefinitely, and communities should prepare for the “Great Unraveling” as you say. Establishing resilient communities that have less need for inputs of energy, food, and capital is prudent planning for local officials to engage in.

Very much on point with how we need to embrace steady state growth and economics to ensure our future on this earth. I am particularly interested in bringing open spaces, wild spaces and micro farms closer to where children live and play. Studies show children with such exposure to the natural world are more likely to appreciate it and want to preserve it.