Dear Ecologist, Don’t Forget About the Economy

Opinion by Alix Underwood

The Ecological Society of America’s (ESA) Annual Meeting concludes today in Baltimore, Maryland. Of the dizzying multitude of topics on the agenda, the most prevalent were wildlife conservation, forest ecology, and climate change. Meeting sessions focused on niche aspects of these topics: threatened wader species on Sonadia Island, the effects of endemic mistletoes on forest-floor invertebrates, and the impacts of warming on interactions between plants and symbionts, to name a few.

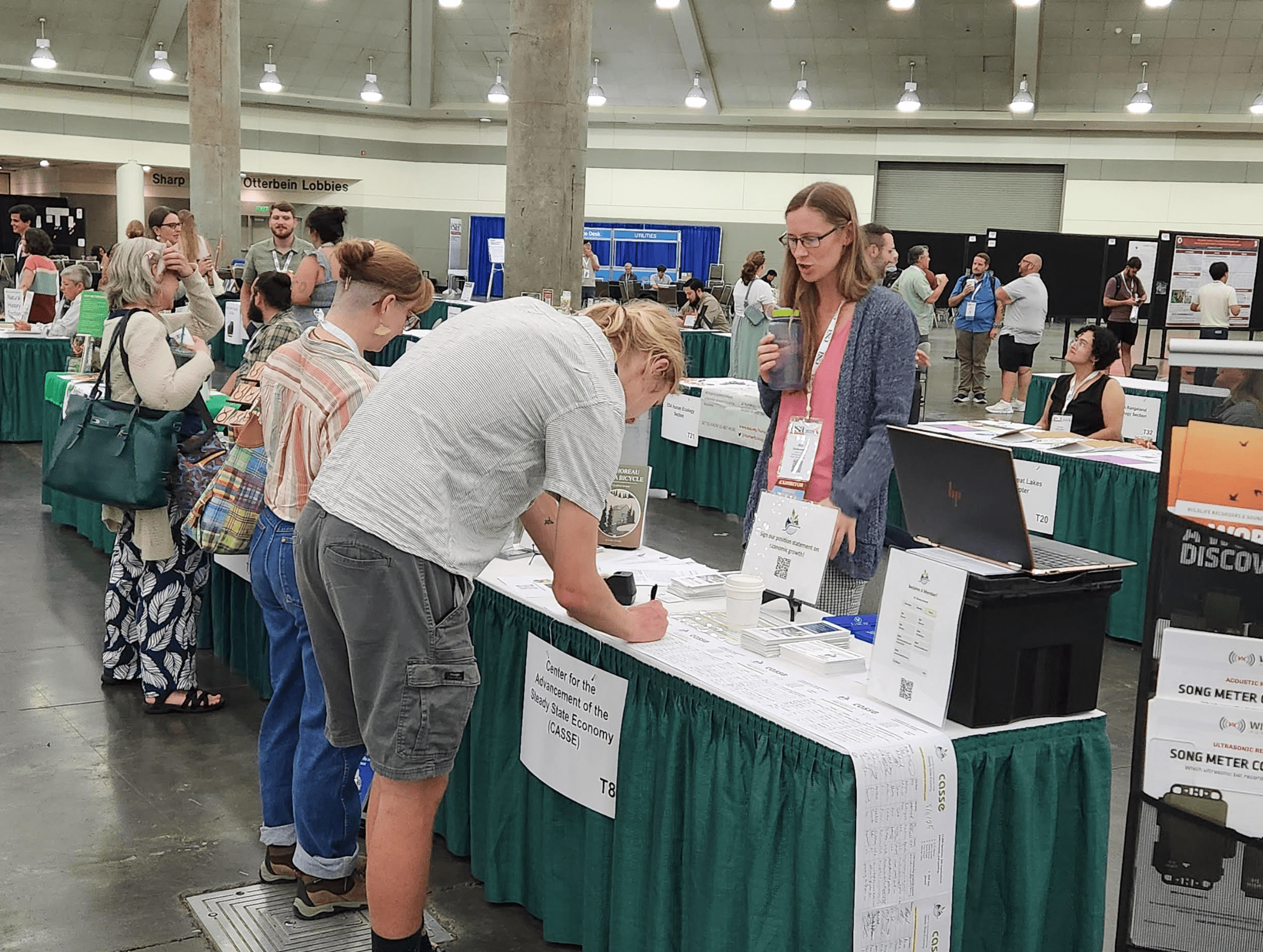

CASSE Executive Director Brian Czech discusses big picture issues with an ecologist.

There weren’t many sessions focused on big-picture issues. The conference was catered to the ecologists in attendance, and their work is just as niche as their session presentations. Some of these ecologists are zoomed in to the microbial level. Alexandra Alexeiv participated in an interview for the Steady State Herald. She studies how interactions between the gut microbiome and the ubiquitous chemical Benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P) affect the brain.

Another interviewee, Yuanming Lu, specializes in Melaleuca quinquenervia, commonly called paperbark. Lu studies its invasion of South Florida vegetation and the biological agents used to control it.

We need specialists like Alexeiv and Lu, monitoring the pulse of ecosystems and testing solutions. However, as long as the human economy continues to grow, solutions created and implemented within the confines of “ecology” will just be stopgaps.

To achieve the systemic transformation necessary to combat the multiple ecological crises we face, we need ecologists to draw connections to macroeconomics. We need them to realize that issues like B[a]P pollution and species invasion will only get worse if the global economy continues to grow. The voices of scientific experts hold a unique sway over policymakers and the general public. The Earth needs those voices in support of movements for degrowth to a steady state economy.

Ecologists Don’t Study Microbes (Solely) for Kicks and Giggles

Alexiev does get kicks and giggles out of microbes. Her voice filled with excitement as she explained that scientists have been researching microbiomes for over two decades, and there’s still so much to learn. “Each microbe carries out different functions, some of which are completely unique. There are microbes that can create their own electricity. There are microbes that eat iron.” She added that she has an obsession with miniature things: “Since microbiomes are small, that’s appealing to some visceral side of me that thinks they’re so adorable.”

But Alexiev doesn’t work toward healthy microbiomes just because they’re cute. She’s keenly aware that humans, and all species on Earth, depend upon functioning microbiomes. Alexiev’s research has revealed that exposure to B[a]P, which is produced when coal and oil are burnt, changes the gut microbiomes of zebrafish. The gut communicates with the brain via the vagus nerve. In this case, the fish’s gut changes led to anxiety, depression, and hyperactivity.

Paperbark’s flaky bark creates a thick litter layer that facilitates wildfires. (Ianaré Sévi, Wikimedia Commons)

“We’ve observed those patterns in humans. Moms exposed to a lot of B[a]P have kids with stronger ADHD symptoms.” Alexiev finds meaning in her research, but she feels it is not enough: “We’ve only just discovered this gut-brain axis is a thing. I only study one chemical effect on one model animal. It’s one little, tiny corner of the issue.”

Yuanming Lu also finds her invasive-species research fascinating. She relates it to her childhood in rural Shanghai. She would feed the ducks with a floating plant that grew abundantly in local creeks. It wasn’t until she was a PhD student that she realized the plant was water hyacinth, an invasive species introduced by the Chinese government. It was introduced to feed ducks, but it turned out not to be nutritious. Water hyacinth spread through the countryside, affecting water availability in Lu’s hometown.

Like Alexiev, Lu wants to protect the environment and translates this to protecting humans. When asked to summarize her research for a general audience, she said, “Basically, kill plants. I tell people how to kill plants, because we need to save our native vegetation.” With a sense of urgency, Lu shared that paperbark in South Florida is contributing to the disappearance of wetlands. “Once that fresh water is gone, it’s always gone. There’s no way to bring the fresh water back.”

From Microbiomes to Macroeconomics

Virtually all the issues ecologists study, from unhealthy microbiomes to climate change, share a common source: economic activity. The production and consumption of goods and services in the human economy cause pollution and habitat destruction that lead to a myriad of other complex ecological problems. As long as the economy grows, those problems will grow.

This clicked with virtually every ecologist I spoke to at the conference. The concept of a steady state economy is easily related to ecological concepts. Alexiev said,

We have this pattern in community ecology, as well: exponential growth simply doesn’t work. No biome can sustain eternal exponential growth, and I would hypothesize that economics works the same way. I don’t think any system can break that balance.

Lu related steady state economics to the concept of “stable states” in ecology. “We say that an ecosystem is in a stable state when several species coexist. That state is hard to disturb, even if you give it a little force. But when we push a disturbance really far, past what we call a tipping point, it will go to another state entirely.”

Why Absolute Decoupling is a Pipe Dream, in Ecologist Speak

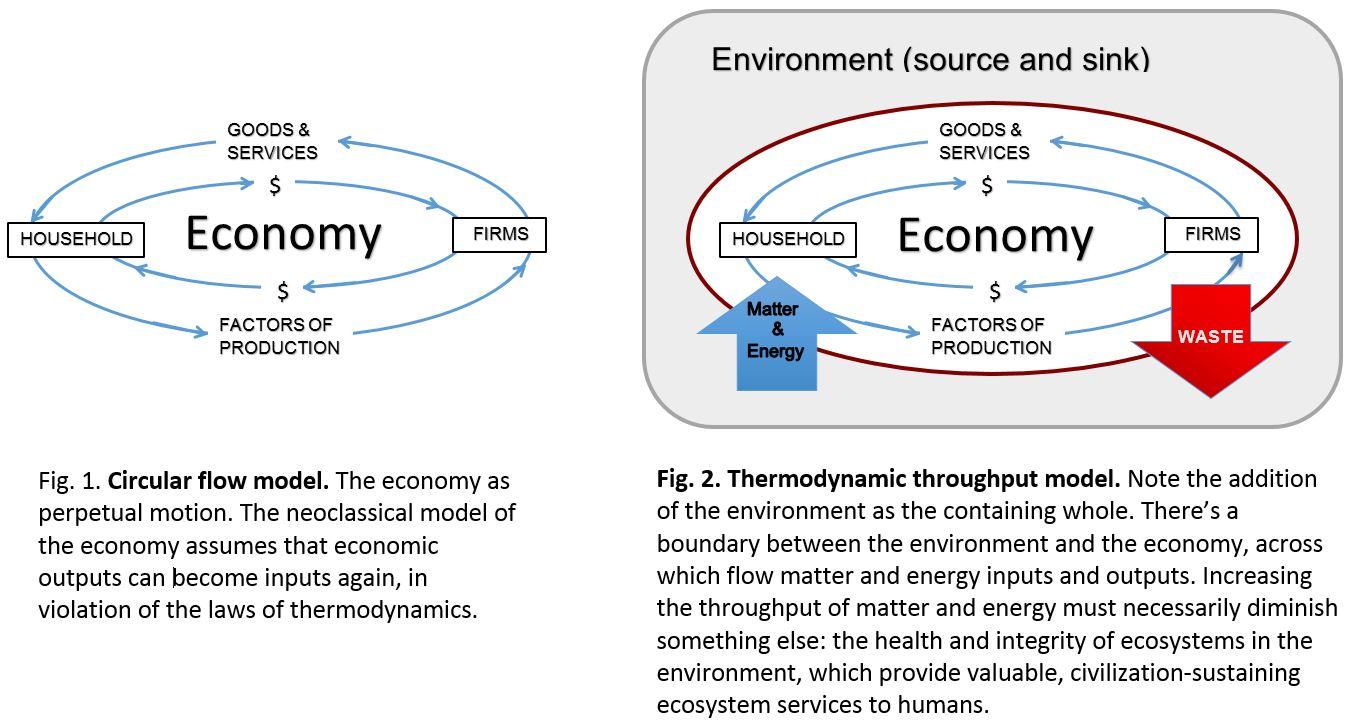

The trophic theory of money struck a chord with many conference attendees. Every ecologist is familiar with the concept of trophic levels, which represent the position of an organism in its ecosystem’s food web. In nature, nutrition and energy flow from plants to herbivores to carnivores.

All sectors rely upon an economic base of natural resources.

In the same way, materials and energy flow from extractive industries to heavy manufacturing to light manufacturing in the human economy. Advances in labor productivity in agriculture, specifically, have enabled the existence of other sectors. In fact, if farmers only grew enough food to feed themselves, there’d be no use for money.

This conceptual model illustrates why we cannot “absolutely decouple” economic growth from environmental impact. Not that ecologists need convincing of that. We received very little “green growth” pushback at the conference.

All Ecologists Should Be Steady Staters

Limits to economic growth was a no-brainer to most of the attendees I spoke with. However, levels of interest and enthusiasm for a steady state economy varied greatly. Many ecologists seemed to feel that a) they don’t know enough about economics to contribute to the discourse, b) they are powerless compared to economists and policymakers, or c) there’s no stopping the growth train, so we’ll just have to face the consequences.

Almost 150 conference attendees signed CASSE’s position on economic growth.

When asked if and how she could see herself supporting steady-state initiatives, Alexiev shared a story. As a graduate student, she went with a group to speak to political representatives in DC. “It felt like a lot of work to get them to listen for five or ten minutes, and we couldn’t convey even a little bit of what mattered to us as scientists. It didn’t feel very hopeful.” Alexiev said she wouldn’t devote much time to something like that again, but she would certainly vote for steady-state policies if given the opportunity.

Lu admitted that she “kind of intentionally ignores the economy.” When asked whether ecologists should care about economics, she said, “Ecologists always say vice versa: Economists, please see us. We need some support from economists.”

But ecologists aren’t powerless—or clueless—when it comes to economics. As professionals immersed in Earth’s processes, ecologists understand fundamental truths about the human economy that many economists do not. What’s more, they tend to be regarded by the general public and policymakers as unbiased producers and communicators of knowledge.

We need ecologists’ support to advance the steady state economy. This is not a call for every ecologist to throw in the towel and become an economist (though ecological economics would benefit from more bright minds). We need experts in niche topics, tracking Earth’s pulse.

Ecologists, this is a call to emerge from your niche occasionally, enough to acknowledge the root cause of the issues you study. You don’t need to start a new movement. There’s an existing movement of academics and activists establishing the need for degrowth to a steady state economy and raising awareness of this need.

If you don’t want future generations to have to keep fighting your uphill battles, show your support for these movements whenever you get a chance. Engage in research collaborations with ecological economists, incorporate economic implications into your research papers, and voice your support for steady-state policies. You can start by signing CASSE’s position statement on economic growth!

Alix Underwood is managing editor at CASSE.

Alix Underwood is managing editor at CASSE.

Alex,

Thank you for the work you are doing. Very important.

I’ve told Brian in the past that steady state needs to address the economic system we live under – capitalism. You mention endless exponential growth. The exponent is simply what anyone and everyone in finance calls return. Return on capital being the essence of the system of capital. But describing the economic system is different than addressing the issue of economics – the body of so-called knowledge taught in universities. For that issue an exploration of neoclassical economics is required.

My work in the past ten years or so is to understand the history of economics and how classical economics was replaced by neoclassical economics. Classical economics was focused on the surplus. How is productive output used, who gets the surplus, etc.

Neoclassical economics drops the whole issue of surplus and its use and replaces it with scarcity and efficiency. Real things like owners, firms and workers are restated as vectors in commodity space. Everything is efficiently coordinated by the market. And once things are de-materialized into vectors, a fetish with math is surely to follow.

In the 20th century and up till today, a concern with classical issues remained in Institutionalist economics and Marxist economics. In this century, Post-Keynsian economics and areas of Heterodox economics have revived a serious real-world approach to the economic system. A proper and relevant economics must be concerned with history.

At bottom, driving out out of the neoclassical fog requires an ontology to be stated. What are the real categories of things relevant to understanding an economy? I’m currently reading James Galbraith’s new book Entropy Economics. I always recommend Fred Lee and his Heterodox approach. Steve Keen’s macro approach where all transactions require a buyer, a seller and a bank is very relevant. Imagine an economics with money.

Best wishes,

Chuck

I like the work you are doing. All I can add is that macroeconomics seems to me as if it may be analogous to the field of medicine (my spouse is a physician so I hear a lot).

In medicine, good work was done in the early 20th century on specific areas that made a real difference. Such as antibiotics. However we have found that things like penicillin are necessary but not sufficient. We are finding that human health is incredibly complicated. One could say that in 1950, medicine was solving for 50 variables. Today it’s more like 2000 variables.

My hunch is that economics is in a similar state: the basic tools and formulas of orthodox economics are still *useful* but they are not *sufficient*.

A final thought: I’m struck by how short attention spans have become. If you develop a pretty good narrative for how humanity took a wrong turn and dove into neoclassical economics, I think it will be helpful if one can boil that narrative down to a couple levels of simplification. It’s sad, but I’ve found that one has to present new ideas in a way that’s almost like a comic strip. Something that takes less than 10 seconds to digest and acts to basically arouse curiosity. If one can get a reasonably intelligent person to pause and think “Wait, what? Is this true? Could this be true?” then people make a decision to allocate more of a scarce resource – their own attention – to the matter at hand.

That was a lot of words from me, apologies.

Thanks Cole Thompson: To your good analogy with medicine, I’ll add that scientific medicine has been good as fixing a lot of problems but not so good at prevention or addressing yawning chronic issues (with variables uncountable).

And good point about attention and the power of brevity. Critique economic growth? Yes. And also grow more time and leisure, relationships and health. Brought to you by limits on economic growth.

Thank you Alix, Brian, for your tireless diplomacy. 150 signatures is good.

For ecologists specifically, I think I’d try to worth with a metaphor involving aquariums or terrariums. This will sound like a bit of cheap stunt but one could have on a conference table a small terrarium (glass box) and an easy to read sign such as “Can the crickets in this sealed world increase by 5 percent each year, forever?”

OK and here’s the cheap stunt part, one could have a second easy to read sign below that reading “The World Bank says YES!” or “maybe yes???” … if a reasonable person stopped and asked, OK, what do you mean by yes? then one could say well, we wanted to make the point that our policy leaders are saying there are no limits – it is absurd, no? Apologies sir/maam for the cheap stunt, but we wanted to get people to think about this obvious ecological problem. And so on.

I am an ecologist and I absolutely support CASSE’s goals.

Some years ago I emailed Brain about the importance of using “stable” rather than “steady” in CASSE’s name. This is because natural systems are not steady. Their components fluctuate continuously. In ecological parlance, a stable system is dynamic! Plus, one could say that steady still implies growth overall … steady growth. That’s what politicians like. Steady growth. Always growing.

In Alix’s excellent summary of the the ESA’s annual meeting, she included the following:

Lu related steady state economics to the concept of “stable states” in ecology. “We say that an ecosystem is in a stable state when several species coexist. That state is hard to disturb, even if you give it a little force. But when we push a disturbance really far, past what we call a tipping point, it will go to another state entirely.”

To Lu’s comment I will add that disturbances do happen in natural ecosystems — naturally if you will — not just disturbances by human activities. Fluctuations happen. However, the sign of a healthy ecosystem is its ability to adapt to the disturbance(s). The result of adaptation and continued health of the ecosystem is resilience. Think about a floodplain. Its basic components, its basic ecology, fluctuates seasonally. Over time, however, it is stable in the sense that it functions beautifully.

I am glad that you were at the ESA meeting and planting the seed of how continued economic growth overwhelms all else on earth. Those attendees who interacted with your tabling will never be able to not think about the message!

All the best,

Jean Brocklebank

Ecologist and elder

Santa Cruz, CA.

Jean Brocklebank: I, too, have pondered over the use of the term ‘stable’ instead of ‘steady’ to describe a dynamic, non-growing economy. In the end, I don’t think it matters which term is used. If a system is stable (as it must be to remain an identifiable system!), it is stable at the macro level. As you say, it will be dynamic, which means it is not really stable at a micro level. For this reason, I think the term ‘steady’, which is used to describe the physical scale of the economy from a macro perspective, not at the micro level, is fine and on a par with the term ‘stable’. I think there would be a problem if the term ‘static’ was being used to describe a physically non-growing economy.

Thank you, Chuck, Cole, and Jean, for the encouragement and valuable insights! Cole, Brian actually told me the other day that CASSE at one point considered using terrariums for outreach or as a membership gift. It’s a great idea!

Good work interacting with ecologists and especially listening to them. I suppose many know the root cause of the problems they study and the damage to things they care about is people and our economic activity, but they need a way to get out of their little narrow concerns. It’s a kind of escapism to study ecology without connecting to the bigger picture. There’s a lot to say about the paradigm of science failing because of this overspecialization and pretense of being “value free” and “objective.” It’s not working.

In 2008, I was invited to write a short paper on ‘macroeconomics’ and ‘biodiversity conservation’ for a special issue of Conservation Biology. I focused on the same things that Alix (and CASSE, generally) is referring to – we won’t conserve ecosystems and the biodiversity of species within them if we remain wedded to the ‘continuous growth’ objective. Indeed, anything (even beneficial) that fails to address the excessive growth issue is tantamount to rearranging deckchairs on the Titanic.

I submitted the paper, but was told to heavily revise it because biologists wouldn’t know enough about the economy to understand it. I replied to the editor that the paper was confined to some very basic economic terms and that it was time for biologists to learn some basic economics (so they could understand my paper), just as economists need to learn some basic biophysical realities. I pleaded with the editor to publish the paper as it was. I successfully managed to convince the editor to leave the paper unedited.

Because Conservation Biology is read mainly by ecologists/biologists, I don’t think many who might have bothered to read my paper, understood it, or saw any relevance in what I said. Sadly, in this world of compartmentalised knowledge (and myths!), I think most ecologists/biologists, many of whom heavily criticise economists, are not prepared to learn some basic economics. We all suffer because of it and, while societies remain fixated with growth, ecologists/biologists will go on recording and documenting the breakdown of ecosystems and the loss of species. Meanwhile the lack of understanding by economists of basic biophysical principles will one day result in the breakdown and collapse of our economic systems.

For anyone interested in my 2008 paper (you may be the first to read it!), here’s the link:

https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01092.x

Chuck Willer: I think the Physiocrats, Classical Economists, and Neoclassical Economists all had something useful to say about ‘value’, although there are different types of ‘values’ (e.g., use value and exchange value).

It’s a myth that markets generate, by themselves, equilibrium prices and quantities – that prices and quantities are the result of interacting demand and supply forces, especially at the secondary (manufacturing) and tertiary (services) trophic levels, and to some extent at the primary trophic level (agriculture and resource extractive industries). It’s also a myth that modern markets are useful because, through an invisible hand, they can produce Pareto efficient outcomes, or something close to it.

On the supply side of most modern markets, prices are ‘set’, usually by an oligopolist, by marking up by a certain percentage above costs. On the demand side, buyers decide whether they want to purchase what is being supplied at the ‘set’ price. Cost plus mark-up determines price (supply side) and demand determines the quantities sold (and therefore quantities produced). If more is demanded at the set price, more is produced and supplied. If not enough is demanded at the set price for firms to make sufficient profits, the product isn’t produced.

On the supply side, the cost should reflect a few things. Firstly, the opportunity cost (OC) of using the natural resources in production. If resource X is used to produce good A, it can’t be used to produce good B, C, or D. An OC exists because, as the Physiocrats understood, a natural resource has ‘use value’ – it is the stuff to which we add use value in production. There is an additional OC (user cost) if the extracted resource is non-renewable or if a renewable resource has been extracted beyond natural regeneration rates.

Secondly, labour and capital are used in combination to extract natural resources (primary trophic level) and add use value to natural resources (secondary trophic level).

Chuck Willer (continued): Because an hour of labour and machine time used to produce good A (add value to natural resources) can’t be used to produce good B, C, or D, there is an OC associate with their use. The Classical economists understood this with their ‘labour theory of value’, although they forgot about the contribution made by capital. There is also a user cost associated with the use of labour and capital (the cost of having to maintain their use value-adding powers).

Thus, the cost to produce good A should equal the (OC + user cost of natural resource use) + (OC + user cost of labour and capital). Price is set by marking above the total cost of supply. Governments should use anti-trust laws to limit the size of the mark-up.

The demand for goods at set prices is determined by buyers’ perception of the use value provided from the consumption/use of final goods. Depending on the characteristics of the goods, people will purchase so much of each good. Most people will avoid paying for public goods, which is why we rely on governments to provide them. We (happily?) pay for PGs in the form of taxes, which are imposed to make resource space for governments to obtain real resources to provide the PGs we desire. Neoclassical economics (utilitarianism) provides some useful insight into our demand for goods, although we know that people demand goods for good and bad reasons. NCEs assume that individuals always now what is best for them, and don’t delve into wellbeing/health issues related to the choices we make. However, for the economic process to work to our full welfare advantage, we need to make sure our buying/consumer habits are consistent with what is good for our physiological and psychological wellbeing. Society’s wellbeing is also dependent on an equitable distribution of individual financial claims on real goods and services.

It’s not a matter of Physiocrats v Classical v Neoclassical. They all have something useful to contribute with regards value.

One other point. Unfortunately, the OC of natural resource use is undervalued; the user cost of natural resource use is completely ignored (El Serafy); the OC of labour is often undervalued (low paid First World workers and grossly underpaid Third World sweat-shop workers); and the user cost of labour and capital is, too, often undervalued (Keynes). Because of inadequate anti-trust laws, price mark-ups above costs are excessive (price gouging). The undervaluing of natural resources and labour, and the price gouging by powerful oligopolists contributes to wasteful and inefficient natural resources use; the counting of the proceeds of natural capital depletion as income; and growing inequalities.

Another factor to consider is that supply curves actually slope DOWN not UP. In a pre-industrial economy, they sloped up because of the increasing marginal cost of production, but in a high-energy industrial setting, the marginal cost of production goes DOWN, taking the supply curve with it. This incentivizes ever-increasing scale of production, which requires ever-increasing scale of consumption. Giant corporations outcompete artisan mom and pops and we shift more and more towards monopoly without regulation.

Robin: At the macroeconomic level (where benefits v costs are largely ignored – simply ‘more’ is considered ‘better’), the marginal cost of a growing economy rises. It is now well above the marginal benefits of a growing economy, which is why GDP growth for many countries is now ‘uneconomic’ (declining GPI).

At the microeconomic level, declining marginal costs, if they indeed are (I tend to think they are very close to constant, at least in the short-run), reflect the costs that firms face/pay, which excludes the many social and ecological costs that go unpriced.

If natural resource prices reflected the true value of their use, the price of non-renewable resources (as they become scarcer) would rise over time. The price of renewable resources would definitely rise if they were harvested beyond their regeneration rates, but, even if harvested below regeneration rates (technically, sustainably), would probably still rise if the harvesting machinery and fuels were made from non-renewable resources (higher harvesting costs). Since there is no substitute for natural resource inputs, the cost of producing goods at the economy’s secondary trophic level would increase, as would the cost of the manufactured goods used to provide services at the tertiary trophic level.

I believe marginal costs at the microeconomic level are constant in the short-run because factors of production are used in fixed proportions (no substitution between natural resources and labour/capital, nor between labour and capital in the short-run, and a small range of substitution possibilities between labour and capital in the long-run). Doubling output at the firm level involves doubling the vector of all inputs (doubling labour-hours, machine-hours, and natural resource inputs). Thus, constant returns and constant marginal costs.

Some would respond that capital is fixed in the short-run (a mainstream myth). Within absolute limits, capital is no more fixed in the short-run than labour.

Your writing is not only informative but also incredibly inspiring. You have a knack for sparking curiosity and encouraging critical thinking. Thank you for being such a positive influence!

Thank you so much, Minnie! This means a lot.

Robin (continued): Mainstream economists play a conjuring trick by measuring labour input in terms of labour-hours and capital input in terms of the number of machines, not machine-hours. If I measured labour in terms of number of workers and capital input in terms of machine-hours, I could assume that labour is fixed in the S-R and capital is variable! Fixed costs in the short-run are real but are due to the way capital and some labour are acquired (up-front payments, unlike non-salaried labour, which is paid in wages/hour (piecemeal)). Fixed costs v variable costs are not due to fixed inputs v variable inputs.

Because mainstream economists assume that capital is fixed in the short-run, they can assume declining marginal product as more labour is added to the fixed capital (decreasing returns) and therefore increasing marginal costs. They need to do this because their mythical idea of perfect competition requires U-shaped average cost curves and upward sloping marginal cost curves. Only in some cases at the economy’s primary trophic level are we likely to see cost curves like this.

If prices of natural resources rose to reflect their increasing scarcity (which they don’t – an error made by Paul Ehrlich that led to him losing a famous bet with Julian Simon), it would be the spot price that would be rising. Firms enter contracts to have factors of production supplied at fixed prices for a short period. Hence, resource input (cost) prices stay constant in the short-run and ought to increase when new contract prices reflect the rising spot prices.

In real terms, contract prices have fallen, which has contributed to the downward sloping long-run MC curves at the micro level for the reason I mentioned above – natural resource prices haven’t risen as they should to reflect their increasing scarcity.

So, I agree with you, but falling marginal costs has more to do with what the market fails to reflect than what costs would look like if markets properly reflected them.