Driving NASCAR Off the American Cultural Cliff

by Brian Czech

In the heart of New York’s spectacular Finger Lakes region last Sunday, 40 drivers lined up to race—for six hours—round and round a circuitous route of doglegs four miles southwest of Seneca Lake. I don’t know who won, and I couldn’t care less, but I do know who lost. That would be people and planet.

Brian France: Billionaire grandson of “Big Bill” France and master of NASCAR branding. (CC BY-SA 2.0, Zach Catanzareti)

Watkins Glen International Raceway, dubbed “the spiritual home of road racing in the USA,” is among six major car-racing tracks scattered about the state parks, national forests, and wildlife refuges of the Finger Lakes region. These six tracks are among 64 in the great state of New York, where they plunder the peace from the Pennsylvania state line all the way over to Long Island, up into the Adirondack Mountains and back down to the shores of Lake Ontario.

It’s unclear why Watkins Glen gets the “spiritual home” title. Could it be for the dozen spirits (eleven drivers and one spectator) who gave theirs up at “The Glen”? Or, maybe it has to do with the historical origins of the raceway, so parallel with the origins of NASCAR. Possibly it’s because of the diversity of racing styles that have convened there, including NASCAR, the Grand Prix, and GT World Challenge America.

Yet my guess is it’s the majesty of the Finger Lakes region that spiritualizes all who enter its hallowed valleys. The sweeping vistas, clear blue lakes, and cool, crisp air are inspiring and energizing to travelers, whether afoot, aboard a bike, or driving a Prius. By the time they arrive anywhere near Watkins Glen, their spirits are lifted and their psychological engines are revved.

And NASCAR capitalizes like a vulture on a Seneca Lake updraft.

Who Is NASCAR?

NASCAR is the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing, LLC. Don’t mistake it for a motorized version of the NFL, NBA, or NHL. It’s not a trade association designed to serve its constituent teams, complete with a commissioner holding teams and players accountable to fans and each other. Rather, NASCAR is a privately held corporation; held in particular by the France family ever since its founding by Bill France, Sr. in 1948.

While it’s not a trade association, NASCAR is somewhat of a syndicate, sponsoring races under twelve “series” across North America and another series in Europe. Most Americans can’t avoid some exposure to the “Cup Series” with its history of Richard Petty and Dale Earnhardt tearing up tires at Daytona, Talladega, and The Glen. The other two primary American series are the “Xfinity Series” for up-and comers—much like minor league baseball—and the “Camping World Truck Series” for pickup truck lovers.

NASCAR fans are made, not born, but with NASCAR’s help, the making starts shortly after birth.

The latter two series remind us that NASCAR is also a brand, unto its own and as a mother brand for all kinds of offspring. The NASCAR Camping World Truck Series used to be the NASCAR Craftsman Truck Series, and for one brief year Gander got in on NASCAR glory.

Even the coveted NASCAR Cup Series has had its spin-off branding, with Winston (cigarettes), Sprint, and Monster Energy all putting their names on the cup over the recent decades of shifting consumer preferences.

Branding and sponsorship vis-à-vis NASCAR is a bewildering phenomenon. A logical start in sorting it out would be with the list of racing team sponsors. Most NASCAR teams have “partners” as well, including “primary partners” that evidently provide more money than regular old partners. NASCAR per se—the France family—has its “premier partners,” “official partners,” and “broadcast partners.”

Then there’s the straight-up NASCAR retail line, spread across a gazillion vendors including Walmart, Dick’s Sporting Goods, JCPenney, and presumably every truck stop along the Interstate Highway System. You can get the goods directly from NASCAR’s own online NASCARSHOP, too. There, for example, you can get your NASCAR T-shirts (over a thousand choices), NASCAR earrings, NASCAR nightlights, NASCAR baby bibs, NASCAR leashes (presumably for pets), and all manner of NASCAR memorabilia and collectibles. But you’ll never collect it all, try as you might, because each year and each new team brings new combinations and permutations of drivers and cars (with a current collection of 730 diecasts in sizes up to 1/24th).

None of this stuff is cheap, but don’t worry; just use code “Lap25”—no kidding—to get 25% off!

NASCAR Money

It’s not easy to assess the financials of a privately held corporation, especially in the USA, but in 2015 Forbes managed to estimate the France family at #53 in “America’s Richest Families” with a net worth of $5.7 billion. Brian France alone (the grandson of “Big Bill”) evidently clocks in today around $1 billion, and the annual gross revenue of NASCAR is about $3 billion.

How do the Frances and NASCAR make all that money? A big chunk of it comes from the $8.2 billion, ten-year television contract NASCAR signed in 2014 for the period 2015-2024. NASCAR gets ten percent of it from the get-go. The rest is split primarily between racing venues and teams.

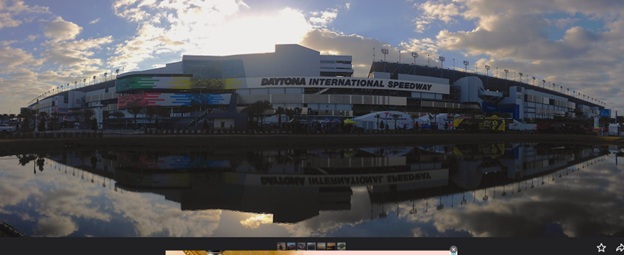

Now imagine if a Dan Snyder or a Jerry Jones (two of the more reviled NFL team owners, for non-Americans) owned legendary Lambeau Field, AT&T Stadium, FedEx Field, and the Superdome, plus ten more of the biggest NFL venues. That would be comparable to NASCAR and the France family with their fourteen racetracks. Along with Watkins Glen, the “spiritual home,” NASCAR properties include the iconic Daytona International Speedway, Richmond Raceway, and Talladega Superspeedway.

Cars and consumers on the fast track at Michigan International Speedway, a property of NASCAR, LLC. (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, Stephanie Wallace)

Since 2019 when the France family bought out the ISC (International Speedway Corporation), they’ve had only one rival in the hosting and scheduling of NASCAR races: Speedway Motorsports with its twelve tracks. Given 39 tracks where NASCAR races are held in the USA (38) and Canada (1), only thirteen are owned by others, including a handful of public entities (Los Angeles County with its Memorial Coliseum, for example).

While NASCAR and the France family used to be at odds with Speedway Motorsports, that seems to have changed since NASCAR took over the ISC. That same year, Speedway went private, emulating the France family. Now they’ve “entered a period of détente,” and we can only imagine the potential for collusion. With a little cooperation, the two entities—especially the France family—can fairly monopolize prime-time stock car racing and scheduling in the USA (which of course you can monitor at NASCAR’s own ESPN-like website).

Either way, NASCAR rakes in close to a billion more annually from its “venue share” of the TV contract combined with ticket sales ($660 million and $194 million in 2018, respectively). Some of the ticket sales go back to the drivers (40 of them in the Cup Series, including 36 chartered) and their teams (17 of them in the Cup Series). But then, teams and charters (the latter analogous to NFL franchises) pay hefty fees back into NASCAR.

Don’t forget those sponsorships and partnerships, too. Sprint, for example, is thought to have paid NASCAR between $50 and $75 million annually for some years before 2016.

All we can say for sure is, if you’d like a challenging accounting job, sign on with NASCAR.

NASCAR and Economic Bloating

What could contribute to GDP at a faster pace, in a fossil-fueled economy, than some of the planet’s fastest, most gas-guzzling machines tearing around in circles? Especially when a NASCAR race typically attracts around 100,000 attendees, many of them driving their own souped-up coups to the raceway in undying tribute to their favorite “sport.” So, when NASCAR comes to town, the chamber of commerce listens.

A NASCAR race can bring in hundreds of millions of dollars in local revenue, most of it taxable and therefore good for the public goose as well as the private gander. Richmond International Raceway, for example, “generates $557 million for the state, including $36 million in local and state tax revenues.”

Don’t get me started on “generates.” At CASSE, we know how money is generated. Money is expended, “fast and furious,” at NASCAR races, but the money is generated at the ecological base of the economy, where it invariably entails an ecological footprint in addition to the one at the raceway. That said, it doesn’t take a genius to calculate that hundreds of millions of dollars are brought to the region of a NASCAR event.

Location, Location, Location. Daytona International Speedway, NASCAR’s corporate home, is next to Daytona Beach International Airport, and now next to a hundred-acre Amazon campus. (CC BY 2.0, Chad Sparkes)

Politicians want to be in on the action, too. Here’s how Illinois state senator Rachelle Crowe (a Democrat from Glen Carbon) puts it: “By bringing the NASCAR cup series to the [St. Louis] Metro East this summer, our state is solidifying its commitment to supporting regional development and driving economic growth throughout the area.”

Conversely, when NASCAR pulls out (as it readily can, given its control of venues and schedules), the locale feels the pinch. That’s precisely what happened at Watkins Glen in 2020, when the staunchly conservative France family moved the big event down to Daytona, blaming it on the differential in COVID regulations between New York and Florida.

NASCAR knows it brings the dough, and plays it up as needed. As Lesa France Kennedy, NASCAR’s executive vice chairperson, puts it, “We are proud to be a part of positive economic development in each market in which NASCAR races.” In a country where economic growth is a hot pursuit at every political level, pitching a race is easy, but NASCAR plays good growth citizen in other ways as well.

NASCAR recently cut a land deal with Amazon, which is developing 100 acres adjacent to Daytona International Speedway. The deal prompted France Kennedy to add, “As Amazon has continued to expand its operations within Florida, we’re excited to play a role in bringing new jobs and a first-class partner to Volusia County. We look forward to this project serving as a catalyst for future growth and development in the community.”

In other words, even where a lot of the townspeople might view NASCAR as an unwelcome intruder, it’s likely to horn its way in by “virtue” of its economic growth credentials. As with so many other questionable pursuits, NASCAR would be far easier to stop if growth itself were recognized as the problem it has become.

The Gas, the Materials, and the Waste

NASCAR has its own version of green energy: Sunoco’s 98-Octane Green E15. It’s literally green; think of it as Mr. Yuk green. By the end of 2016, after only five years of running on Sunoco Green, NASCAR was celebrating “10 million competition miles” fueled by this so-called “biofuel” containing 15 percent “American-made ethanol.”

Note that celebrated phrase “competition miles,” in cars that get 2-5 miles per gallon during competition. That means somewhere between 2 million and 5 million gallons of Sunoco Green was combusted during the five-year period, just during the races. A lot more than that would have been burned up practicing. While most NASCAR races take about two hours (the Watkins Glen marathon being a notable exception), “NASCAR drivers must practice for hours at a time to develop sound habits at a racetrack.” Thus, NASCAR has a ridiculous carbon footprint: approximately 4 million pounds per year.

Another thing NASCAR burns is rubber. About 75,000 tires were used up by NASCAR in 2015, resulting in $35 million of expenditure on tires in 2016.

If we went down the list of supplies and materials used up for all this unnecessary “car circling,” we’d find steel, aluminum, plastic, paint, solvents, glass, fiberglass, lead, copper, titanium, magnesium, wood, sand, oil, and cement.

Meanwhile, NASCAR has tried to paint itself “green” with tree planting and recycling initiatives. Has there ever been a greasier splash of lipstick on a sloppier looking pig? The salient fact remains that the “sport” consists of circling around and around, ad nauseum, in gas guzzlers, for no apparent reason whatsoever than the “entertainment” of a crowd that could probably benefit from a little healthy exercise. Certainly their ears would benefit.

The Symbolism

Approximately 23 years ago, while writing Shoveling Fuel for a Runaway Train, I recall finding (and duly reporting) that NASCAR was “the fastest growing spectator sport in North America.” I was shocked, not because it seemed untrue—it rang true indeed—but because of the absolute collapse of the American conservation ethic. I recall wondering, “What could the world possibly be thinking of us?”

On September 11, 2001 (a year after Shoveling Fuel was published), al-Qaeda terrorists attacked the symbols of American capitalism and the U.S. Government. Almost immediately, President George W. Bush hideously exhorted Americans to “go shopping” and travelling. “Get down to Disney World in Florida,” he said from O’Hare Field. “Take your families and enjoy life, the way we want it to be enjoyed.”

Goodbye NASCAR.

NASCAR fans took Bush to heart, and NASCAR, as always, was ready to capitalize. In the first major spectator event after 9/11, on September 23, 140,000 screaming fans—with 140,000 NASCAR-provided American flags—packed the Dover International Speedway in Delaware. Lee Greenwood sang “God Bless the USA.” The fans chanted as one, “Wooo! U-S-A! U-S-A! U-S-A!”

It’s understandable to have mixed feelings about the Dover event. Americans needed an emotional outlet, and it happened to be a time of year when NASCAR would likeliest provide it. Yet the symbolism was horrific at a time when the rest of the world was trying to sympathize with the USA. Everyone knew American tensions in the Middle East were all about the oil, and here were filthy rich NASCAR teams launching their legendarily gas guzzling noise makers into circles yet again.

The USA blew its opportunity to secure long-lasting international goodwill. Her citizens went shopping, to Disney World, and to NASCAR races. They practiced “consumer patriotism.” The tide of goodwill turned quickly, and in a matter of months one of the prevalent topics over the airwaves and in the think tanks became “Why do they hate us?” While President Bush kept that question focused on Islamic extremists, many of us understood it wasn’t just the extremists, but rather a whole world of nations with a growing resentment of “the way we want it.”

Fast-forwarding to now, consider how frustrating it must be for the world’s other nations to watch our obnoxious NASCAR spew carbon and particulates into the global atmosphere, again and again and again, for almost 75 years, as if we were kicking sand in their faces, while they meet in handwringing futility on reducing carbon emissions. It’s not so much about the pollution and global warming directly attributable to racing—industrial and military sectors cause far more of that—but the symbolism is as stark as a Confederate flag. What could possibly be more symbolic of Americans’ casual disregard of the world citizenry, the global environment, and posterity, than NASCAR?

Fortunately, NASCAR is no longer “the fastest growing spectator sport in North America.” It’s on the decline with all kinds of political and financial problems, thanks to a toxic mixture of Trump, Confederate stain, France family greed, COVID, and environmental concerns. Now is no time to take our foot off the gas. The Frances made their billions, drivers made their millions, and fans had their fun. Let’s welcome the fans back to sanity; we need them on the team and in the pits, if not in the driver’s seat. Together, we’ve got to drive NASCAR off the cultural cliff and let it lie in the rusty pile of American mistakes.

Nothing could be more patriotic.

Brian Czech is CASSE’s executive director.

Brian Czech is CASSE’s executive director.

All I can add is that NASCAR events would be an ideal place to have Pigou taxes as part of the cost to racing teams and spectators. Pigou taxes = explicitly paying for the damage one causes to the commons.

I doubt we’ll ever see it at NASCAR, but in a more perfect world, Pigou taxes (the more specific the better) might help nudge people in the right direction. I would expect that NASCAR will fade away as part of the post World War II cultural bubble that just isn’t interesting to newer generations (along with golf and country clubs, TV dinners, and so on).

There will come a time in the not-very-distant future, when we have used even more of our finite natural resources, when we’ll look back on what we wasted those resources on and ask the question “what were we thinking?” We’ll look back on Nascar, jet skis going around in circles, wars that destroyed countries just to rebuild them again, and conspicuous consumption as the self-destructive nonsense that they are.

I just posted Brian’s profoundly moving article on Facebook, labeling it “Article of the Year”. For reference, thanks to my environmental friends in Bolivia, the Dakar car rally race was finally thrown out, after five years of environmental devastation. Bolivia’s supposedly mother earth government had allowed the race in to boost GDP. The government thought it would stimulate tourism, willfully ignorant of the fact that the people who like to watrch environmental devastation are not the ones who will visit a country for its geographic beauty.

Thanks for writing this article about the environmental impact of NASCAR. The damage is worse since there are numerous small racetracks around the country that have races weekly in the summer or year round. Add to that the impact of ATV trails which are in many state and even national parks. It might help to translate this into how wasting fuel on recreation impacts the price of gas. I’ve seen some places that are switching to electric vehicles, but I despair that anyone is ready to give up this “Circus Maximus”. The only remedy I can see is to enact a tax on the industry and use the funds for the environment.