Introducing the Sustainable Taxes Act

by David Shreve

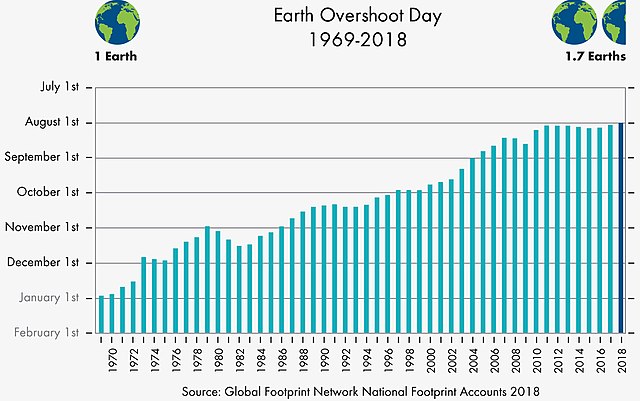

Human economic activity now requires the biocapacity of 1.75 Earths, with occasional and miniscule recessionary or pandemic-related reversals (Global Footprint Network, Wikimedia Commons).

In a world where GDP exceeds our planet’s biocapacity, we badly need new economic policy. In particular, we need to halt the process of unsustainable growth and move toward a steady state economy. The critical question is how to do this while ensuring sufficient economic opportunities, employment, and income for all.

Technological changes are insufficient, despite holding some promise. Neither the agricultural “Green Revolution” nor energy use efficiencies have markedly changed the ongoing overshoot.

Over time, Earthlings have reduced the resource intensity of their economic output, but other factors have offset any potential ecological gain. For almost sixty years, we’ve consistently used more planetary resources and waste absorption capacity than the Earth can replenish. Rising global affluence (desirable in regions of widespread poverty) and population growth account for this overshoot.

Redistribution: The Key to Economic Success and Ecological Balance

If we are to return to a safe ecological operating space, two things must happen. Population reduction is the first. This process is already primed by advances in civil and reproductive rights, which most governments encourage. Economic policy reform is the second, equally critical, factor.

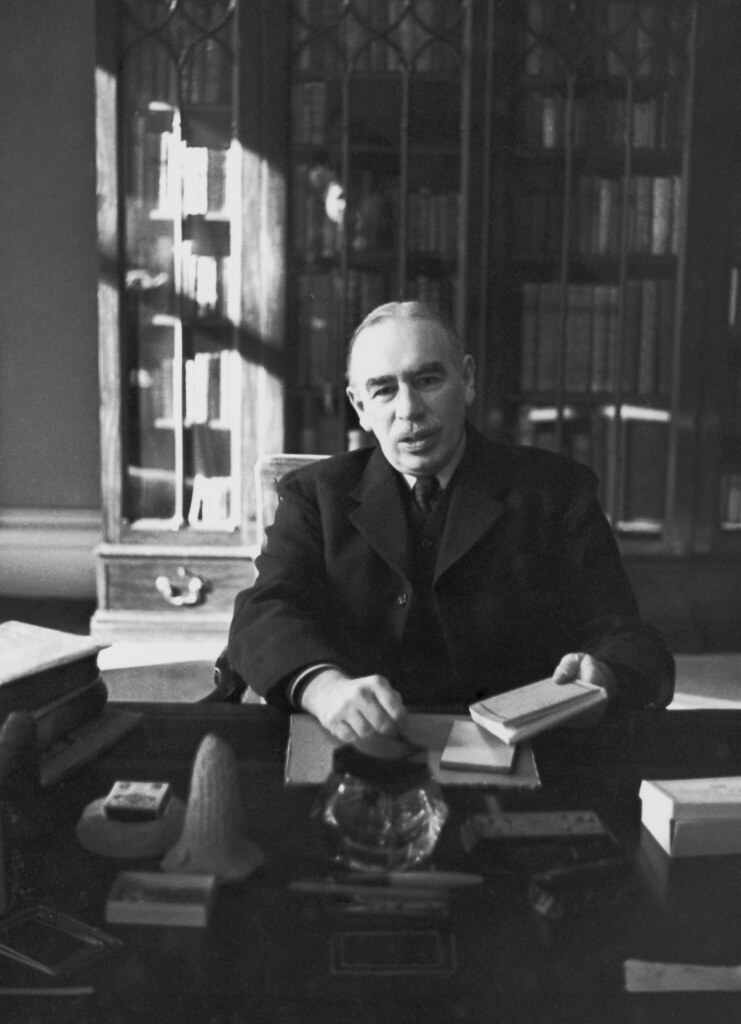

John Maynard Keynes was an English economist and philosopher (Patrick Chartrain, Flickr).

As John Maynard Keynes revealed in The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, if full employment and broad prosperity are the key goals, redistribution of wealth and low long-term interest rates are the essential catalysts. Inherent to this “general” theory is a focus on the broader sharing of resources and income. But resistance to this—especially the call for greater redistribution—was immediate. Anticipating opposition, Keynes proffered a “special” theory expedient, by which deficit spending could compensate for delay or insufficient change. He fully expected that insufficient redistribution and stubbornly high interest rates were likely to persist.

Writing in the midst of The Great Depression, on a planet with a population approximately one-fourth the current, Keynes sensed urgency only when confronting unemployment. An ecological crisis was not imminent. Well suited politically to the dire employment emergency, despite its compromised character, Keynes’s deficit spending recipe rose to the fore. The general theory nearly disappeared. Its critical implications for tax policy also faded into relative obscurity.

As influential economist Joseph Schumpeter lamented, “Most people who admire Keynes accept the [deficit spending] stimulus, take from him what is congenial to them, and leave the rest.” Keynes continued to imagine, however, that when it returned, the general theory could transform and stabilize capitalism. He was just as confident that, along with full employment, it could deliver ecological balance and leisure.

Economic Policy Reform and Taxation

The primary tool for Keynesian redistribution is a broad progressive tax. The spending side of modern fiscal policies carries redistributive power, too. It can steer national income democratically toward needs and the needy to secure broadly distributed gains in “health and welfare.” Yet precisely because these gains are ideally bestowed upon the many, rather than the few, their redistributive power rests vitally upon the way in which they are financed. Which brings us back to taxes.

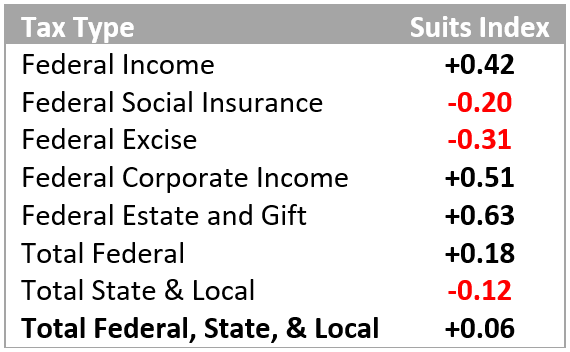

Tax policy has far greater potential than spending policy for positive and efficient redistribution. Yet it also tends to reflect the favored and more narrow choices of a powerful minority. As a result, few tax systems do enough redistribution, a function they are uniquely suited to execute. This is especially so when we consider federal, state, and local policies collectively. Taken together, they generally have been, and continue to be, too flat. They redistribute far less income and wealth than modern capitalist or mixed economies require.

A measure of progressiveness of various types of U.S. taxes in 2007–2009 data. The scale runs from -1 (regressive) to 1 (progressive) (Taxes in the United States: History, Fairness, and Current Political Issues).

The Sustainable Taxes Act, proposed herein, complements CASSE’s Sustainable Budgets Act, for purposes of fiscal balance and equitable and sustainable wealth distribution. Without progressive tax reform, balanced budgets will remain infeasible and a source of instability, not sustainability.

Decades of economic history have shown two key benefits of the more progressive (Keynesian) model of taxation: a) significant income and wealth redistribution and b) fuller financing of key public investments. Written progressively, tax policy draws on income of declining marginal utility. It taxes away, in other words, income that is progressively less valuable to the earner. Minimizing idle wealth, it also curtails frothy speculation and abstruse financial engineering, reducing the need for arcane and time-consuming regulation.

By providing reliable revenue streams, progressive tax policy also makes possible steadier public investment, chosen broadly and democratically. With such latitude, cleaner power grids, efficient transportation networks, and productivity-enhancing human capital investments are more likely to materialize.

Principles of Sustainable Taxation

The key principles of sustainable taxation start with redistribution of income. The tax system must accomplish this broadly and with a maximum of vertical and horizontal equity.

Vertical equity reflects ability to pay. It should be instituted with a system of multiple brackets, the marginal rates for which rise gradually. In the interest of horizontal equity—whereby individuals with similar incomes and abilities to pay find themselves subject to similar tax liabilities—a sustainable tax policy should have no exemptions or deductions.

Corporate income and payroll taxes should be subject to the same principles and standards. The former are often passed through or passed on to owners, workers, or consumers. Because of this, revenue from corporate income tax should be of secondary significance. The principal goal of this type of tax, which should have a simple structure, is to prevent personal income sheltering.

Payroll taxes, which are currently regressive and weighty, should be eliminated. Payroll tax revenue is dedicated to social benefits that are integral to our shared prosperity. Therefore, the government should raise it no differently than revenue for any other integral program. Payroll tax elimination must be coupled with the raising of additional income tax revenue sufficient to replace it.

Taxation can disincentivize unsustainable behavior such as depleting aquifers faster than they are replenished, often for irrigation (NASA, Picryl).

Another principle of sustainable taxation is that severance/depletion tax liabilities should be imposed to reflect the loss of value inherent to our nation’s “commonwealth.” For example, groundwater has surpassing value as an absolute necessity. Therefore, tax liability should be levied on amounts determined to exceed national and regional water usage and conservation standards.

The principle of adequate progressivity should also apply to depletion taxes. These taxes are designed to discourage excessive use or extraction. Therefore, sustainable tax policy should include a system of progressive depletion tax rebates or dividends, which should be paid to all citizens on a per capita basis. The total tax collected, therefore, paid mostly by the nation’s wealthiest persons, would be rebated to all citizens, preserving the progressive character of a sustainable tax code.

Finally, sustainable tax policy must work hand-in-hand with sustainable population policy. Where tax credits or rebates may apply, family-size eligibility limits should be included.

Introducing the Sustainable Taxes Act

Leading with changes to the federal tax code, the goal must be to make more progressive our current, almost flat overall tax structure—encompassing federal, state, and local codes. Given our state of ecological overshoot, tax reform is essential to steady statesmanship. In a world where many political leaders promote only upper-bracket tax cuts, progressive taxation remains an indispensable and widely ignored imperative.

The Sustainable Taxes Act (STA) is a “feeder bill” of the Steady State Economy Act, designed to reform the federal tax code. It has fifteen sections. The first key element, in Section 4, is a 31-bracket, progressive personal income tax. It imposes a moderately graduated personal tax liability, with no deductions or exemptions (owing to the low, reduced rates in its lowest brackets). The personal income tax proposed resembles in significant ways the income tax structure that prevailed during the 1942–1978 period. At that time, the marginal rates ranged from 14 percent to 94 percent and the number of brackets from 24 to 26.

A return to progressive taxation of those exploiting more than their fair share of resources is long overdue (modified from Free Malaysia Today).

Section 5 provides for a corporate income tax with renewed graduation, modestly increased rates, and a modest tightening of global intangible low-taxed income provisions. The proposed corporate income tax reflects the original intent of business taxation, to discourage personal income sheltering. With the STA, corporate tax liabilities passed on to consumers and workers are minimized. It reflects a focus, therefore, on modest progressivity, simple administration, and horizontal equity, so that similar entities are treated similarly. It need not be a source of significant government revenue.

Section 6 mandates the elimination of the OASDI (Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance) payroll tax. Though the spending side of our Social Security program remains moderately progressive, the payroll taxes designed to finance most of its benefits are regressive. For many citizens of limited means, they have also come to carry more weight than individual income taxes.

Designed in the late 1930s to resemble an investment program and to disarm virulent political opponents, we must see Social Security payroll taxes today more realistically. Their original low flat rate has risen by over 600 percent. Social Security is an important spending program and it should be financed appropriately and progressively.

Section 7 includes a modest Estate Tax, designed mostly as a complement to the more significant personal income and payroll tax changes. Because the other changes will also reduce the long-term excess accumulation of wealth, this tax may well become less significant over time. For the present, it must serve, however, as a short-term means of reducing vast and massively unequal concentrations of wealth.

Section 8 provides for a family size credit limit. Introducing a modest change to the way any earned income tax credits or child tax credits may be figured, it is intended to reflect the steady-state emphasis on population stabilization. Its intent is simple: to disallow any credits for children greater than two in number.

Sections 9 through 12 comprise a series of depletion taxes, designed to discourage the overuse of key natural resources. These depletion taxes are complemented by a dedicated fund to which associated revenues are to be directed, subject also to full rebates/dividends.

And last of all, the STA includes two sections that feature a financial transactions tax (Section 13) and a Trust Fund-Rebate/Dividend program (Section 14). The financial transactions tax is designed to complement the larger personal and corporate income tax reforms. Collectively, these reforms should help discourage excess speculation and the emergence of destabilizing and wasteful investment bubbles.

Taken together, these proposed reforms would introduce (or “re-introduce”) progressivity, large enough and sufficient enough to dramatically and positively transform U.S. tax policy. Such progressive taxation is a critical but enfeebled element in our modern economy. Instead, it could be a powerful and vital force for essential redistribution, full employment, and ecologically minded public investment, congruent with a steady state economy.

David Shreve is a Senior Economist at CASSE.

David Shreve is a Senior Economist at CASSE.

This is sorely needed. A way to maybe get some leverage on the overall problem is to dwell on the notion of “externalities”, which is part of mainstream economics. That gets back to, I dump the toxic crud from my factory into the river, because I don’t care, but that crud poisons the people downstream – an “external” cost that I need to be made to take into account.

Everyone wants to dodge their own externalities, but it may be a toehold for drawing attention to the right things.

Given that all women do not have children, it makes more sense to limit tax credits to three children, not two. Otherwise population will have fall below replacement

If replacement level fertility is deemed the ideal target, then a higher (three-child) threshold might make sense, for one needs to recognize, of course, that, especially in our developed nation, the cost of raising children does significantly alter the horizontal equity I recommend in this article. Given our current state of overshoot, however, and the success (economically and with respect to quality of life, in general) of nations which have already made transitions to below-replacement fertility rates, replacement level is not really the ideal. Without ultimately reducing global population, even a more ideal level of redistribution is unlikely to get us to the steady state without insufficient employment and economic opportunity. Moreover, because we know that fertility transitions to replacement levels will be very uncertain and even quite difficult in certain regions of the world, it is incumbent upon the world’s developed nations to lead and to buy a little time for the imperative but much more slow-moving global fertility transition.

Why tax brackets rather than a smooth function?

Why tax credits? These are inherently regressive as many people don’t pay enough taxes to take advantage of them.

I don’t see any mention of taxes on consumption, e.g. sales taxes or value added taxes. Given that consumption is something that one wants less of, as opposed to, say, jobs or income, seems perhaps it should be taxed at higher rates. (Granted income should be discouraged too, as there is not such thing as money that isn’t being used (for consumption of some sort, ultimately)). Such taxes are typically regressive, but there ought to be ways of making them more progressive.

Perhaps there should also be bounds on the ability to deduct interest payments on loans.

Excellent questions. Indeed, even though “brackets” have always been a useful way of showing the public how our income tax system functions (or should function), it is true that few people today flip to the back of the IRS booklet (or its online pages) where they size up the bracket structure. A smooth exponential function could very well suffice, especially if it was deemed ideal to have no upper bound. The widespread lack of awareness of the difference between effective and marginal rates, and the ease with which many can be convinced of absurd “Laffer curve” high marginal rate implications, suggest to me that there is always 1) a public relations element to tax policy; and 2) that we must take advantage of the simple history lesson, by which the high marginal rates of the mid-20th century (aka, the “Golden Age of American Capitalism”) can be shown to have worked exceedingly well. Having brackets, therefore, seems to me a useful way of conveying important political/public relations messages.

On credits (or deductions), while the proposed reforms (or commentary on them) suggest the limiting of any child tax credits, for example, to discourage above-replacement level fertility, the more limiting and general recommendation, here, is to avoid credits and deductions everywhere, with special care taken to eliminate the worst-performing and most regressive, such as the mortgage interest deduction. Note that the proposed bracket structure includes a series of higher marginal rates at the top, but also a series of lower rates at the bottom. These should effectively take the place of targeted credits, and will also underscore the “contribution,” however small, of all citizens in such a system.

As for consumption taxes, their regressive character simply offsets too much of the critical redistributive function. High marginal income tax rates also curb consumption, with one added feature: they discriminate well between spending on luxuries and spending on necessities.