Liberty County, Florida: Globally Important Local Conservation

by Dave Rollo

Sandhill bluffs along the Apalachicola River in Liberty County, Florida, are home to some of North America’s rarest species. (CC BY 2.0, Chris M Morris)

In the “Anthropocene,” human economic activities dominate the Earth, at the immense expense of other species. Scientists are calling this the “sixth mass extinction,” as entire genera disappear 35 times faster than they have over the last million years. This biodiversity loss is happening worldwide, but it plays out at the local level. Likewise, combating the crisis requires local action.

In the United States, effective local action often involves county governance, in coordination with states. Liberty County, Florida, is home to a priceless biodiversity hotspot. Thanks to intentional planning to limit development, the government and concerned citizens have had notable success at keeping Liberty County great, with over half of the county protected for conservation.

But effective biodiversity conservation isn’t as simple as protecting isolated parcels of land. Connectivity via ecological corridors is key. Species depend on dispersal and migration for healthy levels of genetic diversity, which bolsters resistance to disease and recessive genetic disorders. Continued conservation efforts in Liberty County are crucial for the region’s connectivity.

Prioritizing Conservation Efforts

Liberty is the least populated county in Florida, with fewer than eight thousand residents. This affords its ecosystems a low level of impact from human habitation and activity. Almost half of the 633,000-acre Apalachicola National Forest—Florida’s largest forest—is located in the county.

Liberty County is also home to a significant portion of the 202,000-acre Tate’s Hell State Forest and to the outstanding Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve.

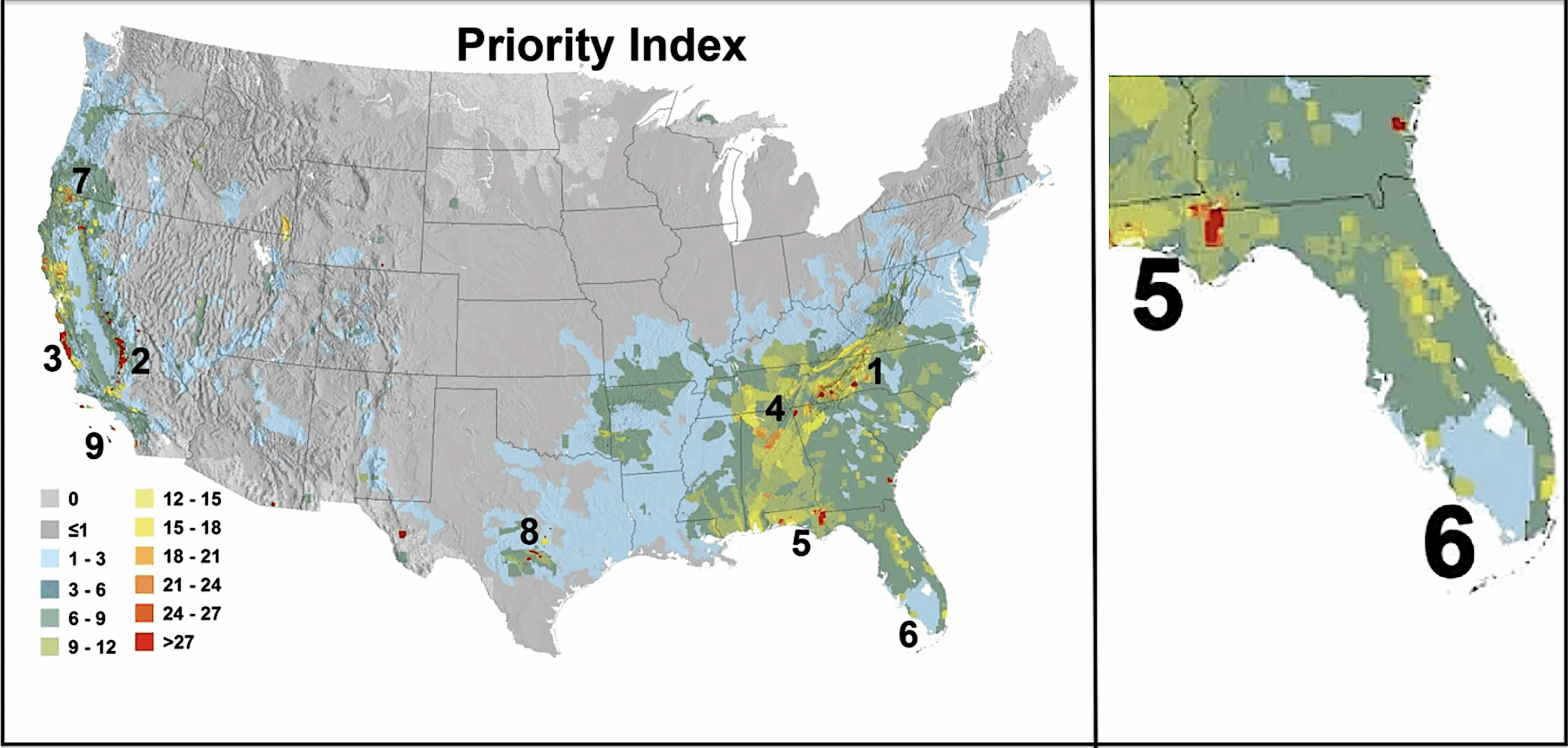

Liberty County has one of the highest cumulative species “priority scores” in the nation. (Proceedings of the National Academy)

Protected land in the county totals nearly 340,000 acres and comprises 64 percent of the county’s land area. These acres, plus protected land in nearby counties, constitute the second-largest area of undeveloped, protected land in northern Florida.

The high degree of land protection is fortuitous, because endangered ecosystems and endemic species make Liberty County a “biodiversity hotspot.” Scientists reviewed all such hotspots in the continental United States and recommended nine “priority areas.” These are areas where urgent action could save species from extinction. Within these areas, smaller areas—priority areas within priority areas—were selected for their concentration of imperiled species and their habitats.

Liberty County is one such concentrated area. It is a focal point of the larger Florida-panhandle priority area. The county provides a hopeful refuge for endangered populations of reptiles, invertebrates, trees, and birds. Not just for protection, but for expansion.

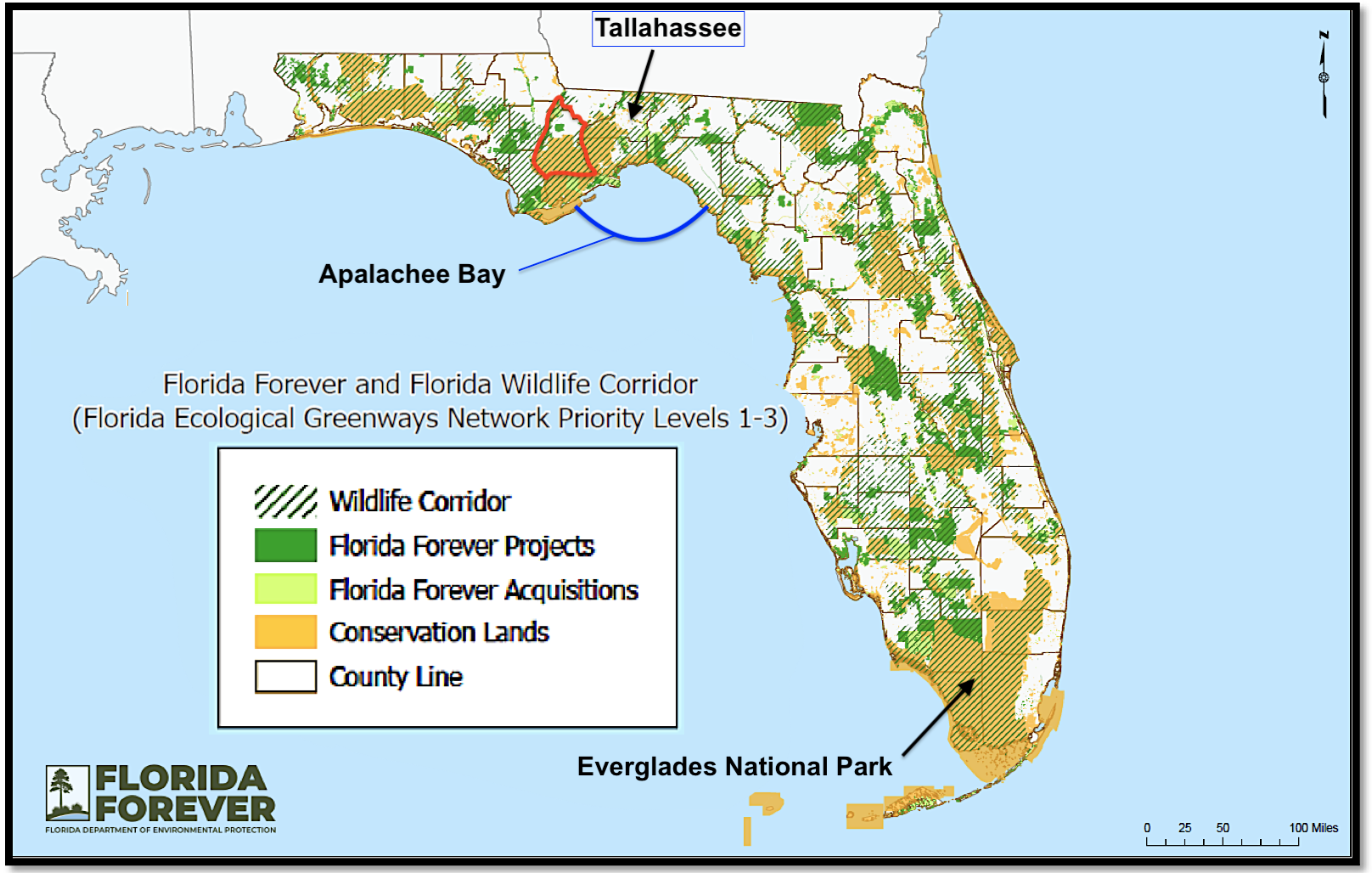

Liberty County as a Key Conservation Node

The protected lands in and adjacent to Liberty County form a vital ecological linkage in the Florida panhandle. They contribute to a corridor that runs from the Florida-panhandle priority area to the Everglades, 500 miles to the south. The Liberty County segment of this corridor connects the forests and springs south of Tallahassee to the coastal marshes and habitats of Apalachee Bay and the greater Gulf of Mexico. The ecological significance of Liberty County’s priority areas extends beyond Florida: They are connected to Georgia and Alabama through upland forests and the Apalachicola and Ochlockonee rivers.

Florida Wildlife Corridor map, with Liberty County outlined in red. (Florida Department of Environmental Protection)

In 2021, the state legislature established the Florida Wildlife Corridor. The corridor consists of the state’s top three (out of five) priority areas for ecological connectivity, determined by the Florida Ecological Greenways Network. To make this determination, they evaluated the presence of rare and endemic species, habitat sensitivity, biodiversity, and effects of projected sea level rise.

The goal is to protect 18 million acres through a combination of fee title acquisition and conservation easements on private land. When the effort began, 10 million acres were already in conservation status at federal, state, or local levels. Since then, stakeholders have successfully protected approximately 250,000 additional acres within the corridor.

It has been a painstaking process, and it’s not over. Conservationists must find a way to meet the 18-million-acre goal as the state grows by nearly 1,000 residents per day. Hundreds of unique species depend on a fully connected corridor to thrive and maintain genetic diversity. Liberty County is a prominent piece of the conservation puzzle.

A Complementary County Plan

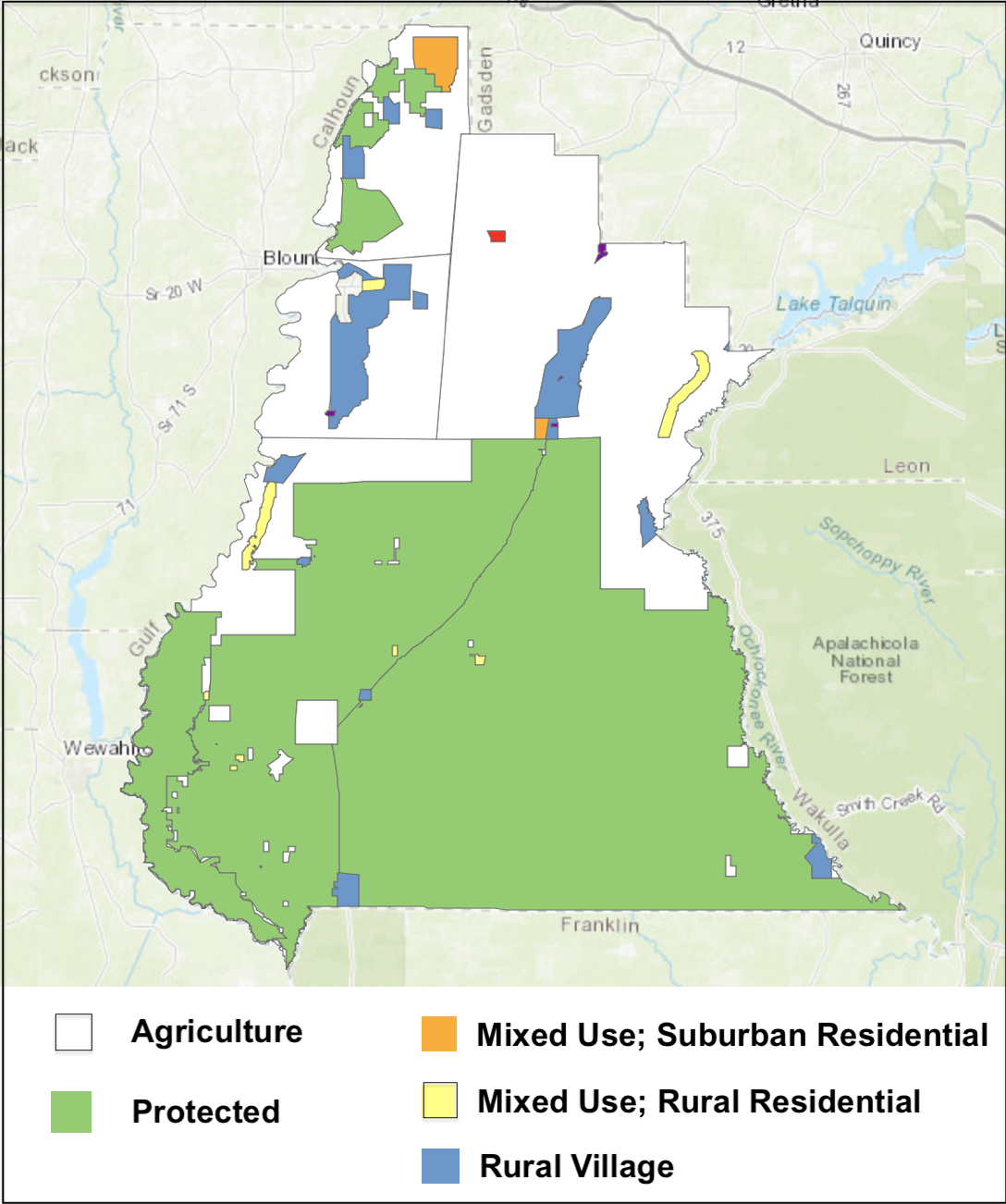

Bristol is Liberty County’s largest population center (1,000 residents), only incorporated municipality, and government seat. Town-center zoning applies to development within Bristol. For land outside of the town, the 2012 county comprehensive plan establishes three developmental zoning categories: mixed use, suburban residential; mixed use, rural residential; and rural village.

Future Land Use Map from the Liberty County Comprehensive Plan. (Liberty Future Land Use interactive planning site)

The first two zoning categories permit two and one dwellings per acre, respectively. They also permit commercial retail development to serve residents. Rural village zoning requires a lower density, no more than one unit per five acres, with no commercial retail development.

Under these three zoning approaches, development can proceed on approximately 15 percent of Liberty County’s unprotected land. The remaining unprotected land is zoned for agriculture, maintaining its rural character.

This is an ideal scenario for conservation efforts. Farmers can sell their land outright (fee title) or sell conservation easements to public agencies or private land trusts for protection. Alternatively, the government can incentivize agricultural landowners—via payments for ecosystem services, for example—to manage their lands with biodiversity in mind. Such programs are already underway in two areas of the state and could be extended to Liberty County and beyond.

Payments for ecosystem services and other programs that rely on ongoing funding can be important stepping stones for staving off land development. However, this approach is subject to the “trophic conundrum.” All money—even money used to pay for ecosystem services or environmental taxes—is generated from a trophic base of agricultural and extractive activity. A steady state economy requires policies that reflect biophysical limits, not the green-growth rhetoric that more money is the solution. In other words, a rigorous conservation ethic—and prohibitive policy as necessary—is the stuff of serious conservation.

State Preservation Programs Target Liberty County

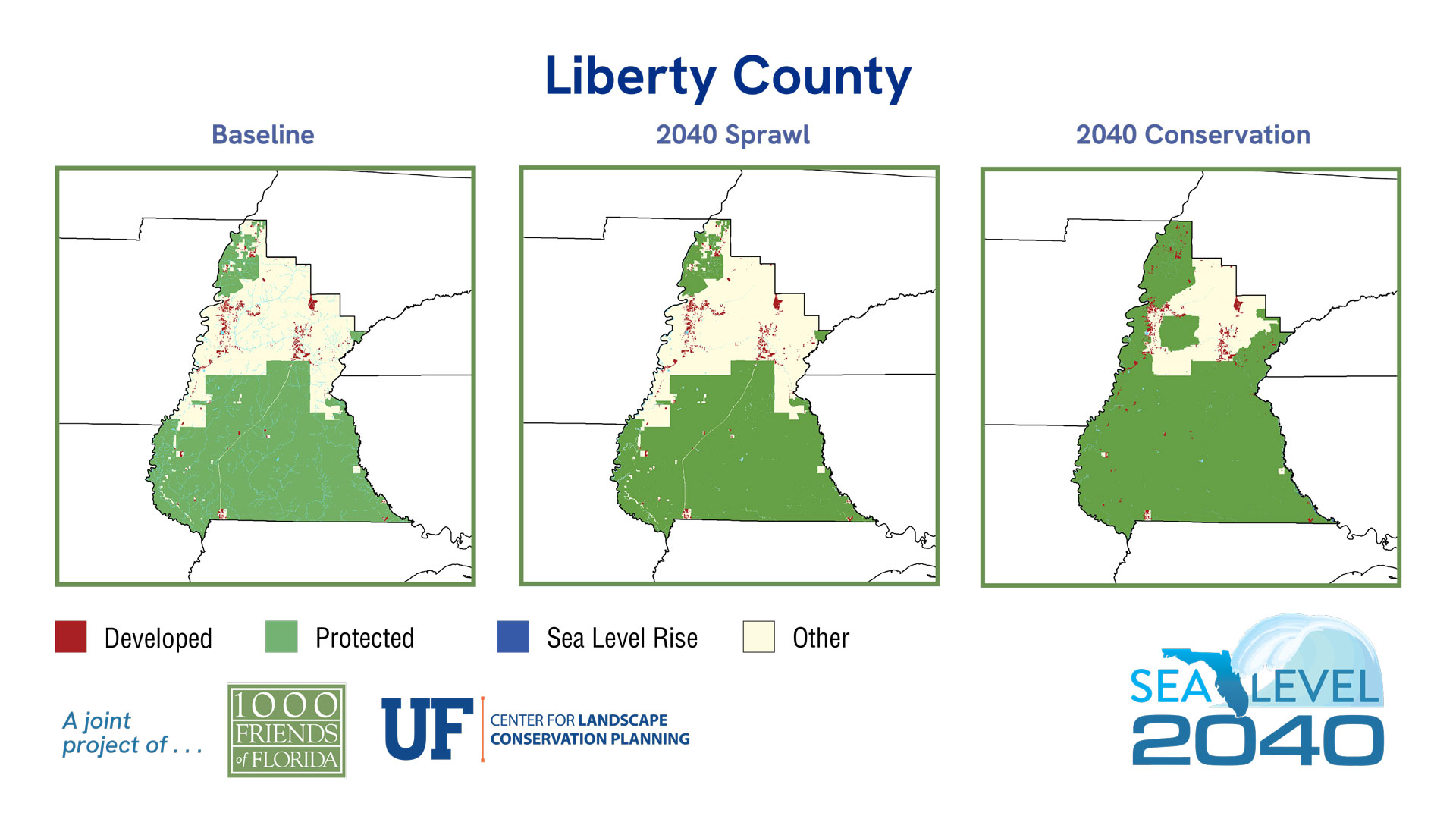

In coordination with the conservation group 1000 Friends of Florida, the University of Florida’s Center for Landscape Conservation Planning (CLCP) produced maps of counties within the Florida Wildlife Corridor. These maps illustrate three conservation scenarios.

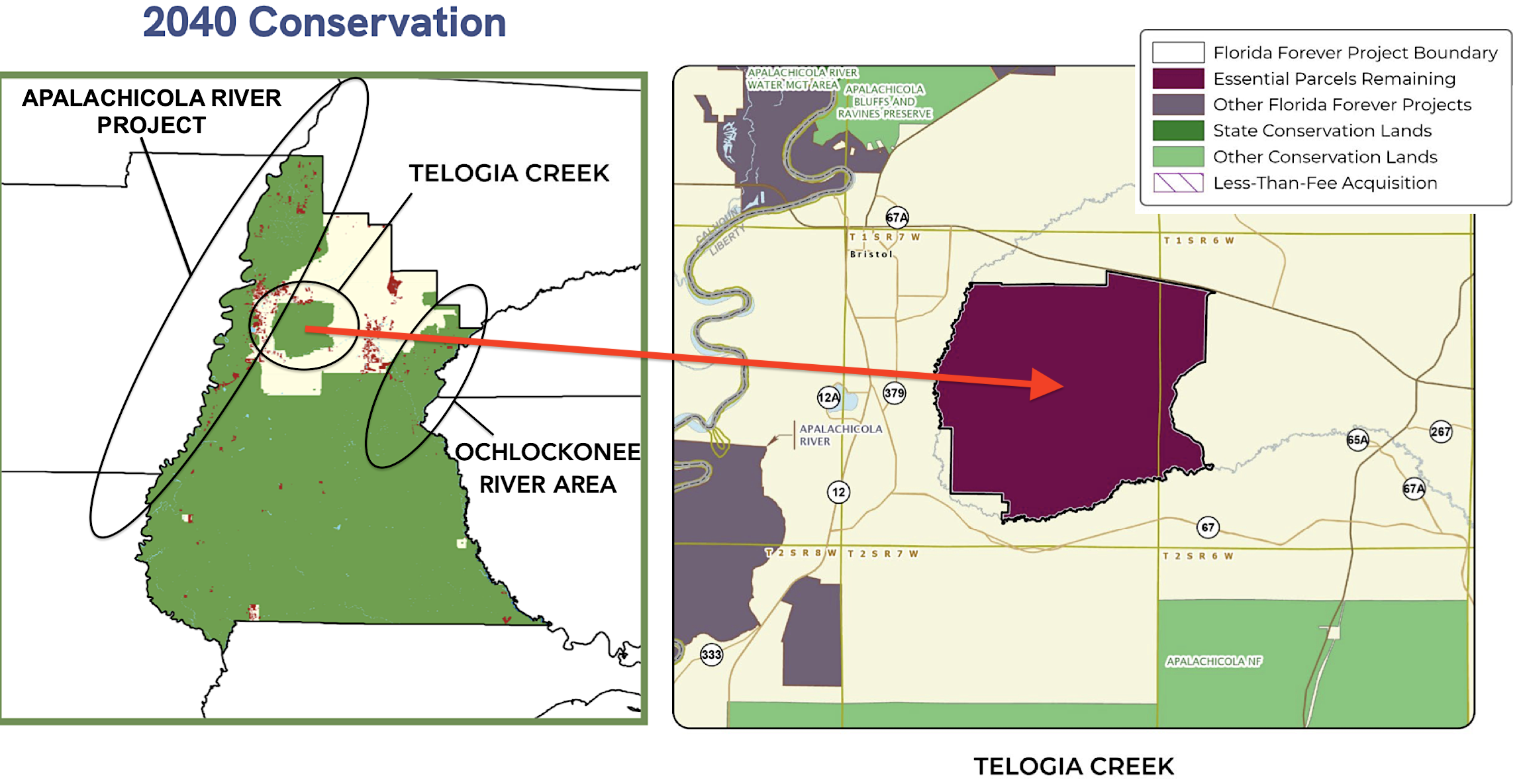

Recent acquisitions have brought the 2040 Conservation scenario closer to realization. (1000 Friends of Florida/UF Landscape Conservation Planning)

The first, “Baseline” map reflects the land’s current use: protected, developed, or undeveloped. The second and third maps project land use in 2040 if current development trends continue (“Sprawl”) and under an optimal “Conservation” scenario. Because much of Liberty County’s land is already protected, and because county government has limited areas for development, sprawl is projected to be minimal. Conversely, given the county’s key location for regional connectivity, 79 percent of the land is protected in the optimal Conservation map.

On Target for 2040

Conservation groups have three primary focal areas for Liberty County. The first comprises riparian areas along the Apalachicola River. The second is an area along the Ochlockonee River. This area provides an inland wildlife corridor extending north of Tallahassee into the Red Hills region. The third focal area is a large forested area, currently zoned for agriculture, along Telogia Creek, which is a tributary of the Apalachicola.

State funding made the 12,400-acre Telogia Creek acquisition a reality in 2023. This area is listed on the Florida Forever Priority List, a project of the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP). Telogia Creek features pine plantations, forested wetlands, and imperiled and rare species habitat.

Florida Forever’s expanding Apalachicola River Project and a close-up of the Telogia Creek acquisition (right). (1000 Friends of Florida/UF Landscape Conservation Planning map (left) and Florida Department of Environmental Protection (right))

The acquisition connects numerous adjacent conservation projects, such as Apalachicola National Forest and the Apalachicola River Project. The latter is the highest priority project on FDEP’s Critical Natural Lands list. (The Critical Natural Lands list classifies high-priority lands for conservation. These are placed on the Florida Forever Priority List if they are eligible for acquisition through the Florida Forever Program.)

“Liberty County is in a really strategic location,” according to Dr. Tom Hoctor. Hoctor is the Director of the Center for Landscape Conservation Planning (CLCP) at the University of Florida. In 2010, Hoctor worked with Carlton Ward to begin the campaign to convince the state to adopt the Florida Wildlife Corridor. In an interview for the Steady State Herald, Hoctor pointed out that Liberty County’s key habitats extend into neighboring counties. They extend into Wakulla County to the east and Franklin County to the south along the coast.

“Liberty County serves as a significant hub for the network of connectivity within the corridor, and fortunately, it doesn’t suffer from the development pressure that we see in other parts of the state, such as central Florida.”

Establishing Habitat Corridors: Isolated Protected Areas Are Not Enough

As a self-described “optimistic cynic,” Professor Hoctor acknowledges the pressures of Florida’s high population growth rate and development patterns that threaten ecosystems and their connectivity. Yet, “residents of Florida say both in polls and local referenda—often with a 3:1 margin—that they are willing to pay higher taxes for greenspace protection. And, it is notable that the Florida Wildlife Corridor unanimously passed in both the state house and senate.”

Tom Hoctor is director of the University of Florida’s Center for Landscape Conservation Planning. (University of Florida College of Design, Construction, and Planning)

Dr. Hoctor added, “What we’re seeing in more rural counties is an outlook to try to maintain their rural heritage and economy.” Fortunately, not every county aspires to have exurban sprawl.

In addition to conducting research—mostly related to the corridor—Hoctor teaches conservation biology, landscape ecology, and planning. He presents the “Cornucopian vs. Limits” distinction in his classes and speaks assuredly of the reality of limits: “Rest assured, limits are real, and we are really in a race against time here in Florida.”

Public sentiment in Florida is shifting, with growing support for conservation. In 2024, Martin, Clay, Lake, and Osceola Counties passed land-conservation referendums, and citizens overwhelmingly voted “YES.” And in 2025, grassroots activism succeeded in getting the state legislature to adopt the Florida State Park Preservation Act, restricting developments like luxury lodges and golf courses in state parks.

In recent decades, a greater appreciation has emerged among conservationists for genetic diversity and migration patterns as key to staving off extinction. In many places, linkages between protected areas are now being prioritized. Those spearheading local efforts should foster this shift, considering the regional and even global significance of the ecological systems they work to protect. Liberty County serves as an example of how we can keep our counties great, preserving their precious biodiversity via collaborations between private entities, governments, and civil society.

Dave Rollo is a policy specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

Dave Rollo is a policy specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

Glad to hear Liberty County is doing good work. I was just thinking that there’s yet another good reason to preserve ancient ecosystems: medical science. Years ago I chatted with a researcher from UC Davis, and he mentioned that from time to time some really amazing complex chemical compounds would be identified in ancient forests and so on. Trying to summarize an area I’m not familiar with, it sounds like “complex ecosystems give rise to complex organic molecules.”

And sometimes these complex molecules from ancient and unique ecosystems turn out to have magical healing or preventive properties for us humans. So, to a developer pondering carving up the map of Liberty County and paving over chunks of it, I would say: the cure to whatever ails you and your loved ones, Mr. Developer, may well lie right within those ancient forests.