No Steady State Economy with Global South in Debt Crisis

by Alix Underwood

This week marks the fourth annual International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD4). Leaders of governments, international organizations, and financial institutions meet in Seville, Spain, to “reform financing at all levels.” Global South countries and advocacy groups from across the world hoped this would be the moment for a UN Framework Convention on Sovereign Debt.

According to Didier Jacobs, Oxfam International’s Debt Relief Advocacy Lead, the idea of this framework has been around for at least 20 years. That’s because there is no bankruptcy law for sovereign states. A convention that legally binds all international lenders would provide some sorely needed certainty for borrowers (and lenders).

Hopes for the framework convention were dashed before the conference even began. Negotiations took place in New York to determine the agenda for Seville. There was a standoff between borrowers, led by African nations, and creditors, led by the European Union and the United Kingdom. (The United States withdrew completely and is not attending FfD4.) As often happens in international policy spaces, wealthy, creditor countries leveraged their power to block meaningful reform. The adopted “Sevilla Commitment” establishes only a mechanism to provide intergovernmental “recommendations,” nothing legally binding.

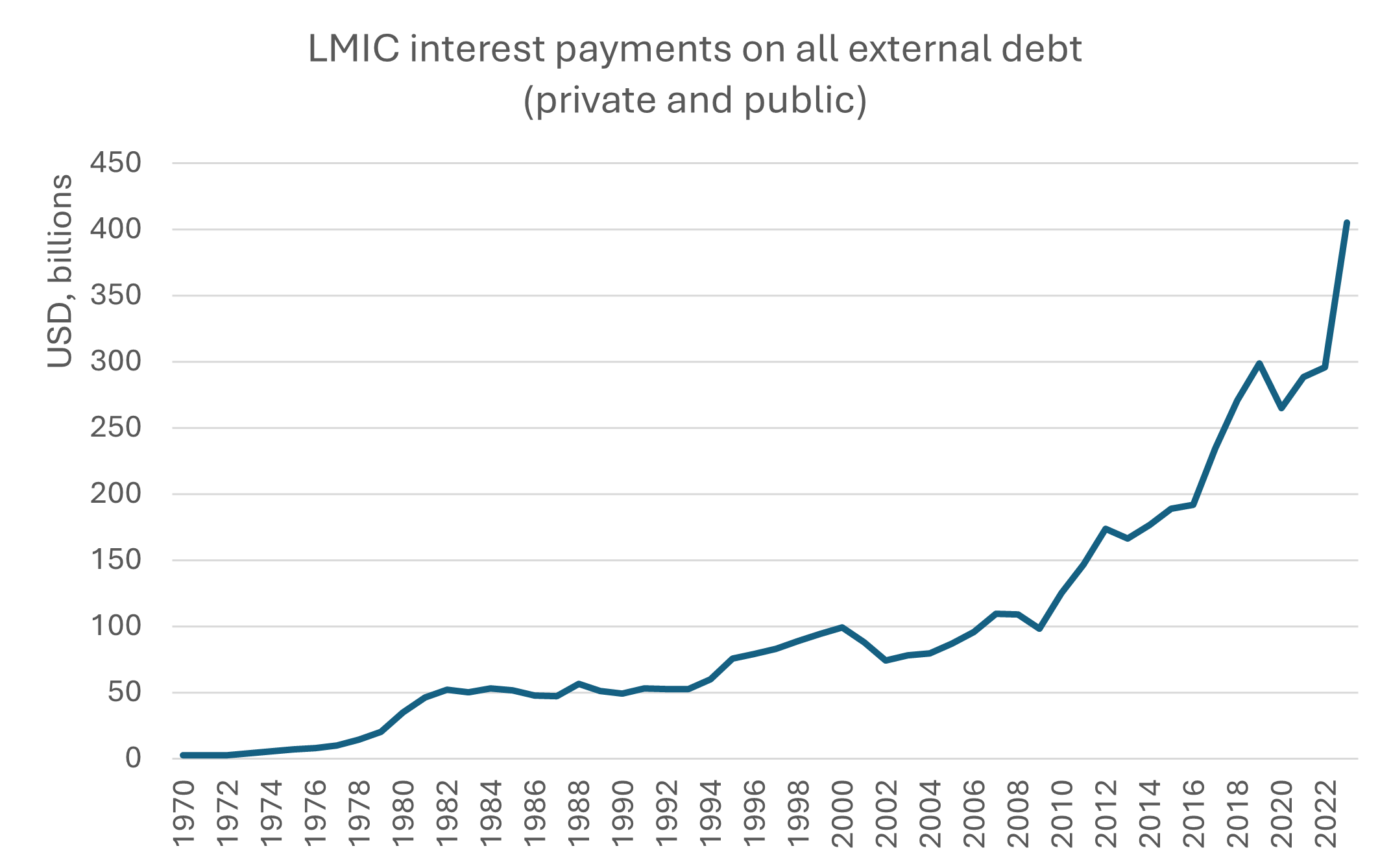

For LMICs, the cost of repaying debt—especially debt owed to private creditors and to China—is increasing. (World Bank Group, International Debt Statistics)

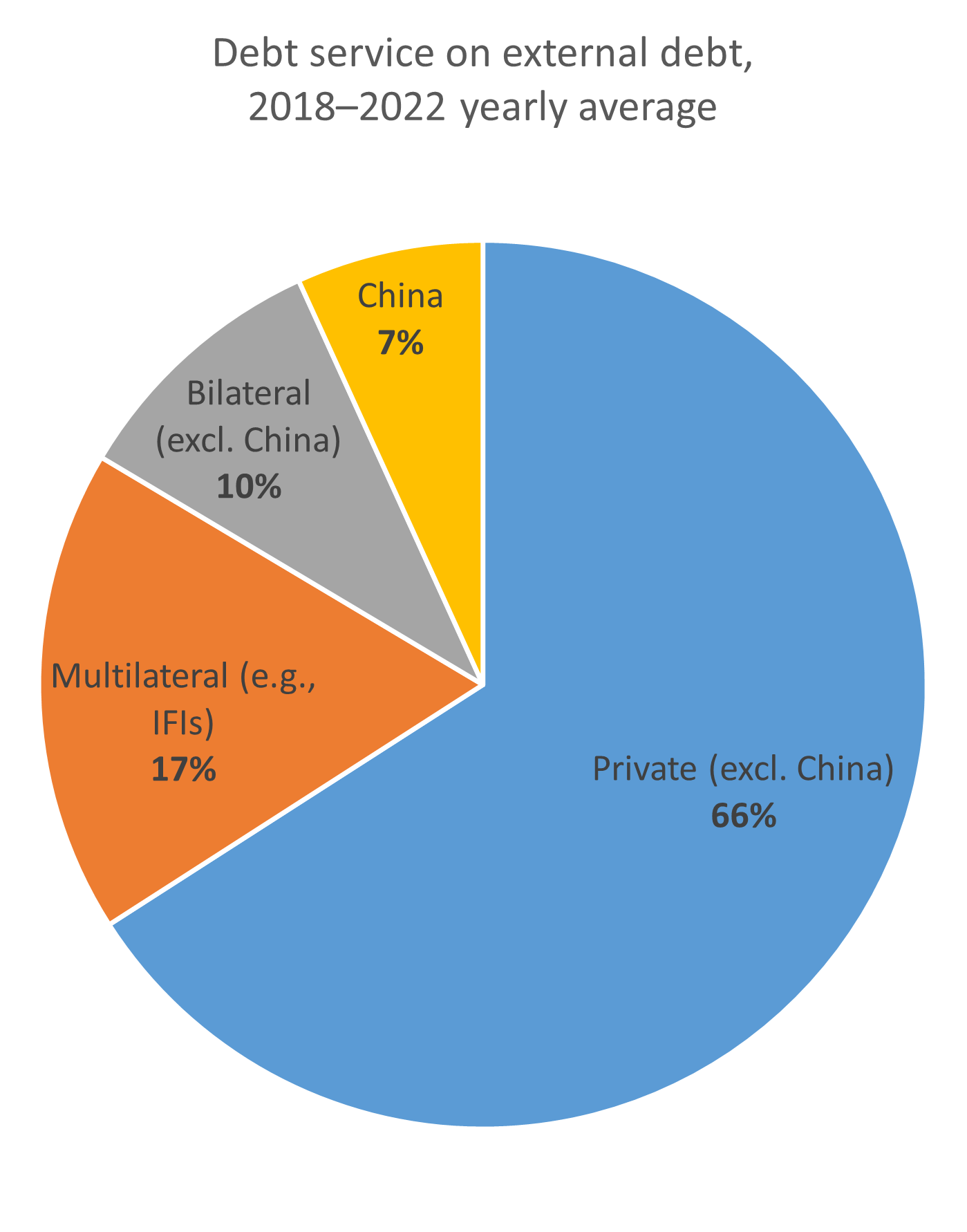

We need international financial reform more urgently than ever. Lending to the Global South is often associated with international financial institutions (IFIs) like the International Monetary Fund. IFIs are infamous for imposing “structural adjustments”—privatization, austerity, trade liberalization—on countries in desperate need of funds. These harsh conditionalities have forced many countries to turn to a different, even more predatory, kind of lender. Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) now owe the majority of their external public debt—61 percent in 2021—to private creditors.

Ballooning debt to private entities is largely responsible for recent sharp increases in LMIC interest payments. They rose 10 percent from 2023 to 2024, when net interest payments on public debt reached $921 billion. 48 LMICs, with a cumulative population of around 3.3 billion people, spend less on education or health than they do on interest payments.

Large debt obligations contribute to a twisted reality: About $3 trillion is transferred from the Global South to the Global North every year. This means countries still suffering from colonialism, and now from neocolonialism and the worst effects of climate change, are funding the continued growth of rich countries.

Public Debt: Escaping the Doughnut Hole or Falling Further In?

Shrinking too-big economies is only one side of the steady-state story. For an equitable steady state economy, countries in the hole of Kate Raworth’s doughnut need to increase consumption to establish a social foundation. Many of these countries’ ecological footprints are smaller than their biocapacities, meaning they can sustainably increase consumption. These countries are straining their economic engines, increasing fossil fuel use and natural resource extraction, and often achieving economic growth. But rather than establishing that much-needed social foundation, much of this wealth is flowing to nations that should be degrowing.

Of course, the situation isn’t always as simple as rich lenders trapping LMICs into growth that’s not benefiting them. In an interview for the Steady State Herald, Oxfam’s Didier Jacobs pointed out that loans make much of the growth in LMICs possible: “It’s when loans are not well invested that debt crises occur, and that is too often the case.” The expectation is that wise investments lead to enough growth to pay off debt and improve social services.

Should Zambia’s two million smallholder farmers, extremely vulnerable to climate shocks, shoulder the costs of debt to the Global North? (UNDP Climate, Flickr)

Even when LMICs fulfill this expectation, interest payments lead to growth in high-income countries (HICs), an outcome antithetical to steady statesmanship in international diplomacy. What’s more, “enough growth to foot the interest bill and then some” becomes less realistic as multiple crises—climate change not the least among them—unfurl in the Global South.

According to CASSE Senior Economist David Shreve, public debt itself is not the problem: “We need large and sometimes ballooning debt levels in any nation (North or South) if we accept the current maldistribution of wealth within and between nations.” As long as there is a yawning gap between the rich and the poor, public debt will be necessary to meet social needs, such as full employment. Acknowledging this, many advocacy groups call for wealth redistribution via tax reform alongside debt reform.

Out of the Frying Pan and into the Fire: From IFIs to Predatory Private Lenders

Private entities now dominate the international lending landscape. (ONE Data, International Debt Statistics)

For a country struggling to make ends meet, private loans with fewer conditionalities are enticing. The catch is that they come with shorter maturities (borrowers have to pay them off more quickly) and higher interest rates. Rates from “official” lenders have also increased. The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) base rate stands at around three percent (additional charges make the actual cost much higher).

However, private creditors buy bonds with yields as high as eleven percent, in the case of African countries (U.S. bond yield is four percent). Some private entities lend with the expectation that countries won’t be able to keep up with these high rates and will default. According to Didier Jacobs,

“These private creditors, known as vulture funds, play the game of litigation. They buy bonds on the cheap when the country is already very much in trouble. People expect them to default on debt, so the price of bonds is very low. When the country defaults, instead of negotiating a restructuring, the vulture fund goes directly to the court to claim the full value of the debt. They can make a huge profit this way.”

The majority of these lenders are based in New York City and London. They are beholden only to the laws of these jurisdictions (hence the need for a UN Framework Convention). The private-creditor problem came into sharp focus in the mid-2000s, when Donegal International sued Zambia in a UK court. They sued the country for $55 million on debt they had bought for just $3 million. The judge reduced the award but still ordered Zambia to pay over $15 million.

The Case of Zambia

The infamous Donegal lawsuit exacerbated an already dire debt situation in Zambia. By 2021, 38 percent of the Zambian budget was going toward debt repayments. Simultaneously, Zambia’s education spending declined from 17 percent of the budget in 2016 to 12 percent in 2022. Health sector spending declined from 9.5 percent in 2018 to 8 percent in 2022. Zambia spent less in 2021 on education, health, water, and sanitation combined than on debt servicing.

When it comes to these social goods, Zambia is squarely in the doughnut hole. In 2022, 32 percent of the population did not have access to basic drinking water services. 63 percent did not have basic sanitation. In 2024, 30 percent of Zambia’s youth were receiving no education, employment, or training.

Zambia’s malnutrition rates are among the highest in the world. Over a third of Zambians are unable to meet minimum-calorie requirements. The country suffered its worst drought on record in 2023–24. With the impact of climate change on food supplies, things aren’t going to get easier in Zambia nutritionally. The impact on Zambian financial capacity will be just as harsh, given the trophic origins of money.

Despite having contributed next to nothing in historical greenhouse gas emissions, Zambia’s economy will be disproportionately impacted by climate change. According to the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative Index, Zambia ranks 137 out of 192 countries in climate readiness. It has high exposure to climate impacts and low capacity to adapt. To rectify this injustice, HICs are approving climate finance—$155 million so far for Zambia via the Green Climate Fund.

Hakainde Hichilema, Zambia’s president, has taken a controversial approach to solving the country’s debt crisis. (Theophilus Maurice, Wikimedia Commons)

This show of justice looks quite sorry when compared with the resources the same countries are draining from Zambia. Zambia hemorrhaged $4.5 billion in external interest payments from 2010, when the Green Climate Fund was established, to 2023. HICs’ climate finance is even less heartening when one considers that much of it is more interest-bearing loans.

In November 2020, Zambia’s debt obligations became untenable. The country missed a $42.5 million interest payment to international investors, triggering a swift downgrade in Zambia’s credit rating. This severely limited Zambia’s access to global finance. (Countries need new loans to pay off old loans.) In a desperate position, Zambia accepted a $1.3 billion IMF loan with strict conditions. These conditions have forced the government to implement austerity measures, slashing subsidies and raising taxes. Such structural adjustments are infamous for disproportionately affecting poorer members of society.

Winds of Change?

According to Fiana Arbab, Policy Advisor on IFIs and Gender Justice with Oxfam, “The current global financial architecture is not broken, it is working exactly as it was designed: to concentrate wealth and power.” (Her point precisely echoed Confessions of an Economic Hit Man, by global finance insider John Perkins.)

It is one thing to fix a system that everyone agrees is broken. Humans are ingenious problem solvers. It is quite another thing to change a system that is benefiting its most powerful stakeholders. The ultimate solution of debt cancellation would require these powerful stakeholders to forgo trillions of dollars.

However, Jacobs is hopeful that “eventually the creditor countries will see that the writing is on the wall.” Returning to the subject of the UN Framework Convention on Sovereign Debt, he said that African countries have put their foot firmly in the door. No matter how hard creditor countries try, they can’t close the door.

One of many attention-grabbing displays in Seville, this imbalanced scale was coordinated by Oxfam and symbolizes the influence that the super-rich have over politics. (Alex Fidalgo)

It doesn’t look like anything legally binding will come out of FfD4 on the debt front—maybe at the next conference. However, Oxfam is still taking advantage of the stage set in Seville. They have hosted official conference events and more attention-grabbing displays, including a giant imbalanced scale in the street. In the meantime, Jacobs is focused on Oxfam’s plan B: incremental reform of informal spaces, such as the Paris Club, where debt policy is developed.

African civil society and Greenpeace also took to the streets in Seville, staging a protest in the blistering heat. It featured a giant blow-up of Elon Musk as a baby, wielding a chainsaw and seated atop a blow-up Earth.

With “days of action” coordinated around the world, the “Pay Up! Cancel the Debt! Change the System!” campaign is demanding cancellation of all public debts by all lenders for all countries in need. They are also calling for the Global North to fulfill its climate finance obligations via new, non-debt-creating finance. They demand that international financial institutions be recast as democratic global governance bodies. They call for a UN Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation, in addition to a convention on debt.

Recognizing the resistance to change from within institutions like the UN, Debt for Climate is launching a campaign for “citizen debt audits.” Their proposal is for social movements to evaluate public debt and “identify illegitimate, odious and illegal debts, to then reject their payments.” The appeal of this strategy is that it doesn’t depend on the political will of Global North creditors.

That said, the World Bank and IMF have also been pushing for “radical” debt transparency, perhaps the lowest hanging of activists’ demands. An increasing number of low-income countries are providing loan-level debt disclosure and conducting audits. The hope is that enabling the international community to better assess the public debt situation will pressure both borrowers and lenders to make more responsible decisions.

It’s a step in the right direction, but we urgently need a lot more than transparency if we are to achieve an equitable steady state economy. The Global North clings to its wealth, failing to recognize the ecological and, often, social toll exacted by every dollar. And we fail to recognize that the toll of this wealth has been exacted most heavily in the Global South.

As long as we see wealth as something that some deserve and others do not, systemic reform of the international debt architecture will evade us. Many ecological economists contend that we can still achieve decent living standards for all within Earth’s safe and just operating space. But we need to wrap up the rat race of economic growth and start sharing Earth’s abundance, before we’ve gone too far beyond planetary boundaries to achieve a steady state economy.

Alix Underwood is managing editor at CASSE.

Alix Underwood is managing editor at CASSE.

Man, what a trap this all is for the Global South. Sigh.

It’s really hard for me to wrap my head around a sustainable civilization that relies on interest from loans to incentivize banks to make those loans. I probably need to brush up on my reading of steady state economics with regard to finance – that has always been the murkiest area of SSE for me, personally.

I’m glad the African countries may be starting to get together. As is, they get defeated one by one, but in a sort of union, they’d have leverage to change this.

Per Capita Income is mostly ENTROPIC FOOTPRINTS & not a measurement in SUSTAINABILITY

ECONOMY depends on ENTROPIC CAPITAL & ENTROPIC FOOTPRINT

PCI does not contain

ENVIRONMENT COST

SOCIAL COST

CULTURAL COST

It is mostly an accountancy measurement

You have to emphasize on Ecological Footprint & Biocapacity for Sustainability

You do not have Developed Countries in the world but High Energy Consuming Countries

Germany has shown that with Nord Stream Blasts and Sanctions

You have to get rid of (Reserve) Fiat Currencies

This is good for SSE

Also the value of Entropic Capital (Gold/Commodities) will go

Nobody can be against DEBT RELIEF

This is not the main issue

Correction:

Value of Entropic Capital (COMMODITIES /GOLD) will go up in price

USD should be replaced by GOLD to qoute economic meaurements

China has to take leaderdhip in DEBT Relief

USD will fall in value in the near future

This is automatic Debt Relief

Note that the Vatican has recently issued a report on this issue, authored by Joseph Stiglitz and Martin Guzman, “The Jubilee Report – A Blueprint for Tackling the Debt and Development Crises and Creating the Financial Foundations for a Sustainable People-Centered Global Economy” (June 2025, 30 pp.)

The report is available at https://www.ncronline.org/files/2025-06/Vatican%20Jubilee%20Report%202025.pdf.