Federal Land Management Reaches Full Sellout Under Trump

by Kirsten Stade

While U.S. federal land management agencies have seldom been bastions of conservationist vision, their level of regulatory capture has reached a new high in the Trump era. From opening up protected areas to oil and gas development to efforts to sell public lands outright, the current administration and Congress are looking to turn over public lands to extractive industry for its private profit.

We are in a new era of public lands mismanagement, with industry profit elevated far above public lands’ potential for recreational enjoyment and wildlife, soil, and water conservation. An effort to literally sell off public lands was halted this summer in the Senate. But a number of actions that would give extractive industry far more control of 88 million acres of these lands are still in play.

The thousands of lakes and streams, rugged cliffs, canyons, and sandy beaches of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area in northeastern Minnesota are at risk from copper sulfide mining, now that the Trump Administration has removed protections. (Brian Hoffman, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Most of these actions roll back special area designations that prevent logging, mining, and oil and gas development. These designations include roadless area protections across 40 million acres of national forests. They also include a mineral withdrawal that protects the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness of Minnesota from copper sulfide mining. And they include protections that stop new oil and gas leasing from destroying vital archeological sites in the unique ecosystem surrounding Chaco Canyon in New Mexico. The administration has also already initiated actions that would weaken endangered species protections that safeguard habitats across an additional 87 million acres of public lands.

Fossil Fuels Trump Wilderness and Wildlife Habitats

Many of the Trumpian public-lands wrecking balls have been trained on lands with fossil fuels whose extraction creates wealth for the corporations intimately enmeshed with the administration.

The Trump Administration is reopening the coal-producing region of the Powder River Basin of Wyoming and Montana to new lease sales. (U.S. Bureau of Land Management, Public Domain)

Just in October, the administration announced its plan to open the 1.56 million acre coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil and gas development. The area is vital to the vibrant ecosystem of the largest national wildlife refuge in the United States, hosting caribou, millions of migratory birds, wolves, grizzly bears, and polar bears. It was closed to oil development when Congress designated the Refuge in 1980. Trump’s 2017 tax bill opened it back up, and the recent decision restores leases canceled by the Biden administration.

The pending sellout of Alaska’s iconic refuge is a particularly egregious example of the Trump administration’s penchant for trading irreplaceable wild places for short-term fossil-fuel industry profit.

Along similar lines is a recent announcement that the administration will open 13.1 million acres of public lands to coal mining. Coal sales are likely, for example, across 2,600 square miles of public lands in Montana and Wyoming. These are expected to yield 600 million tons of coal, while ravaging habitat for the sage grouse and other threatened wildlife.

The Energy “Transition” that Never Will Be

Administration officials defend the move to open up public lands to coal mining by referencing soaring electricity demand. Data centers used to drive artificial intelligence are projected to account for almost 30 percent of all U.S. energy demand.

With no likely slowdown in energy demand for all the other things that power modern techno-industrial society, expanded renewable energy development cannot obviate the need for continued coal extraction. Due to rising demand from AI and from global economic and population growth, coal use has nearly doubled since 2000. This is despite dramatic advances in renewables during that time.

The reality is that there has never been an energy transition in the history of humanity. With continued economic and population growth, new energy sources only add to those already in use, rather than replacing them. This was true as we supposedly moved from burning wood to also burning coal; today we burn more wood than ever before. It was true as we discovered and began to exploit oil. The oil-burning vehicles that transport more than 90 percent of goods and people across the planet , and the concrete that carries them, are manufactured using coal. And it is true as we “transition” to “renewable” technologies, which rely upon trace metals mined using diesel-powered machinery.

A coal-powered steel mill. Steel, a major building block of cars, roads, buildings—and of windmills, EVs, and solar power infrastructure—is one of the major components of modern techno-industrial society that is difficult or impossible to decarbonize. (Pixabay, CCO 1.0 Universal)

A good portion of the hype around the supposed “renewable energy transition” (which is neither a transition nor renewable) is founded on an unfortunate conflation of the concepts of energy and electricity. While renewable sources like solar, wind, geothermal, and hydropower meet almost one-third of the global demand for electricity, that electricity accounts for only 20 percent of total global energy demand. The remaining energy use is for industrial processes like steel and concrete production that rely upon the burning of coal, and others like mining, drilling, shipping, and aviation that are diesel-powered or otherwise extremely difficult or impossible to decarbonize. This includes, of course, the energy used to build wind turbines and solar panels themselves.

The fact is that fossil fuels still supply more than 80 percent of total global energy demand. The accelerated development of renewables will only continue to drive that demand.

With or without an energy “transition,” continued growth in energy demand is bad news for public lands in the United States. While the Powder River Basin of Wyoming and Montana is the most productive coal-producing region of the United States, 570 million acres of primarily public lands are leased for coal extraction across the country. Combined with an additional 24 million acres of public lands currently leased for oil and gas production, these lands are responsible for a sizable proportion of U.S. fossil fuel production and roughly a quarter of its carbon emissions.

A Bipartisan Consensus on Selling Out Public Lands

The Trump administration is looking to put this production into overdrive. But its lust for fossil-fuel plunder should not be seen as a complete departure from how previous administrations viewed public lands. Public lands oil development soared under pro-growth Biden. Although the pro-growth Obama Administration made fossil fuel development on public lands somewhat more difficult, it made solar and wind development—with their associated impacts on birds, bats, and sensitive wildlife and habitat—much easier.

It seems that a growth agenda, regardless of political party, is tough to square with environmental protection.

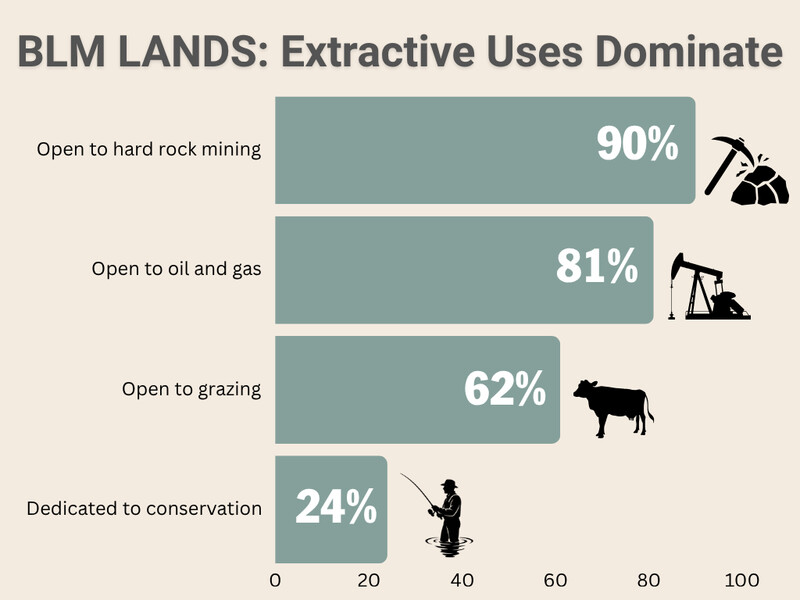

Most energy development has taken place on lands managed by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM). As the largest U.S. public lands management agency, the BLM oversees 245 million acres of surface public land and 700 million acres of subsurface mineral estate. From its inception in 1946 the BLM has been captured by livestock, mining, and logging interests.

The U.S. Bureau of Land Management, the largest U.S. public lands management agency, leaves the vast majority of its 245 million acres open to fossil fuel development and other forms of extraction. (Center for Biological Diversity)

Although BLM’s belated Organic Act, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) of 1976, elevates conservation interests above those of extraction, most administrations have ignored its clear direction. FLPMA’s conservation mandate for BLM includes designating and protecting Areas of Critical Environmental Concern throughout its holdings, but these areas and their ecological treasures are still vulnerable to mineral exploitation. The Secretary of the Interior could address this vulnerability by withdrawing ecologically significant BLM lands from their default availability for new mineral exploration, but the vast majority have not been so protected.

The notoriously industry-friendly BLM is not the only agency that treats its land holdings as repositories for fueling economic growth. Even the National Park Service—with 85 million acres of iconic scenery, wildlife habitats, and recreation lands under some of the strongest protections—has not been untouched by our voracious demand for economic growth.

Drilling and prospecting for oil has for decades compromised sensitive National Park System lands like the Big Cypress National Preserve, the 729,000-acre preserve that channels 40 percent of the water that flows into Everglades National Park. Two oil fields within Big Cypress yield a small amount of oil obtained by injecting acid and other chemicals into rock formations. This is low-grade oil that the Park Service prioritizes over the integrity of an ecosystem that shelters imperiled species and filters drinking water for nine million Floridians.

A Return to Business as Usual Is Not Enough

As the Trump Administration seems determined to leave no fossil-fuel deposit unburned, it is tempting to long for a mythical bygone era of soundness in public lands management. Andy Kerr is a veteran conservationist who badgers state and federal agencies. Over four decades, he has succeeded in badgering them into establishing or expanding a staggering number of protected areas. When asked what the next sane administration could do to rectify the harm Trump has done to public lands, Kerr avers:

Desert Paintbrush and a breathtaking view in Wyoming’s Shoshone National Forest. The recreational, spiritual, wildlife, climate—and ecosystem benefits of intact public lands are priceless. (Kirsten Stade)

“I’m waiting for the first ‘sane administration.’ The public lands conservation community should not want to go back to normal. ‘Normal’ is losing species, ecosystems, watersheds, and viewsheds.”

Ultimately, our public lands will remain at risk from energy interests for as long as GDP growth remains the lodestar of policy and practice. Fossil fuels are at the heart of the growth machine that has transformed native ecosystems and wildlife habitats into strip mines and strip malls, monocultures and grazing pastures. It is only a commitment to degrow our economy—and maintain it at a smaller steady state—that will allow these concentrated units of fossilized solar power to remain in the ground, where they belong. The potential to conserve the climate-buffering, water-filtering, wildlife-sheltering, and health-enhancing benefits of public lands is reason enough to redouble our efforts toward advancing such an economy.

Kirsten Stade is a staff writer at CASSE.

Kirsten Stade is a staff writer at CASSE.

It’s an appalling situation, to be sure. Alas I don’t have a brilliant solution, but I overall I think it is the lack of long-term thinking that fuels this catastrophe.

The US in particular seems prone to this. The US was able to adopt a paradigm of expand, grab, and take – sort of a hunter gatherer mindset – as opposed to something along the lines of understand, plan, and manage well, or sort of a farming mindset.

Perhaps if individuals can selfishly see the advantages of long-term thinking for their own lives, this might shift the culture of policy in the US. I say “selfishly” because I’ve benefited from pursuing long-term goals that took decades to realize. The future tends to arrive quicker than most think.

There are also two specific examples of organizations with an explicit long-term focus: Amazon.com (with regards to success as a private company), and China (with regards to scientific and technological development). Both have achieved impressive results, albeit results that are not at all compatible with a sustainable world.

But I think the general point can be made: think long term, e.g. maybe 50 years out for young individuals, and 100 years out or more for societies. Individual people in the US would be vastly better off — I think individuals would start to see benefits take shape in their lives in about 5 years — and perhaps, just perhaps, this could shift the culture around national level policy.

Cole Thompson: Hunter-gatherer societies are some of the most successful societies. Aboriginal Australians successfully lived on the Australian continent for 60,000 years. They were successful because they were oikonomic in their mindset, which meant their thinking/actions were very much long-term focused.

That’s more than I can say about post-H-G societies (since the advent of agriculture), which have existed in the form of institutionalised chrematistics. Institutionalised chrematistics has evolved with changes in knowledge and technology, and with concessional offerings made by ruling psychopaths to appease the plebs to maintain stability of the system that delivers to psychopaths their power and wealth. The system eventually collapses, as it has many times before (the demise of past empires) and did so in the early twentieth century (the collapse of Neoliberalism 1.0). That led to WW1-Great Depression-WW2, which cleared the slate enough to permit the closest thing to oikonomia in many post-H-G societies (immediate post-WW2 period). It wasn’t entirely oikonomic because it was still based on growth as a prime social objective that itself ran into problems in the 1970s and led to Neoliberalism 2.0, which is where we are now.

We won’t extricate ourselves from this situation with individual actions, even if they are based on long-term planning. The total is not the same as the sum of the parts, and if we all do the ‘right thing’ but the scale of what we do collectively is unsustainable, thinking long-term as individuals won’t cut the mustard.

Sustainability is a macro problem requiring a macro solution – namely, a cap on the rate of throughput to bring it within the ecosphere’s carrying capacity. It then becomes an issue of how the throughput is distributed between individuals and, since the throughput is useful to us in the form of goods and services, how the throughput is best allocated, which requires maximising use value (not exchange value) at least cost.

Thank you for recognising the non-renewability of ‘renewables’ and the fact that regardless of the source of energy, we can’t keep up the current rate of consumption. Environmental groups in Australia seem to have successfully convinced people that all our problems will be solved by renewable energy, because they know they will lose support by telling people that they have to drastically curb their lifestyles to be truly sustainable.

Thanks, Kirsten Stade, for writing an essay useful across the ideological spectrum. The piece is a good shout out against current policies undercutting the health of public land. And it’s important to see the ways these actions are newly amplified versions of long-standing erosions of public protections. And for other spots on the spectrum, for those already with environmental leanings, this piece makes a good read to get beyond generalizations about hurts to park lands and preserves. Oh? What in particular? The essay provides helpful and concise specifics on “an appalling situation,” as Cole Thompson puts it. The particular examples here, combined with more public education, might wake more people to take action, from the individual changes that Thompson hopes for to the structural changes Philip Lawn calls for. Moves toward a steady-state economy could both benefit from the awakening to these land policies and prod in these directions, including with moves beyond expecting that use of renewables will solve current pressure on nature, as Lee Maddox points out.

And more, I appreciate the historical nuance of this essay in pointing to the lack of any energy transitions in history. Better to call them energy expansions, or expansions in the palette of energy use. And alas, the processes used to build reduced carbon production, with hopes to maintain current and growing levels of consumption, themselves add to carbon output. All good reasons to curb assumptions for constant economic growth.