Recipe for Obesity: Ultraprocessed Foods and Economic Growth

by Gary Gardner

Ultraprocessed starts at breakfast. (Frank Chamaki, Unsplash)

People of a certain age will remember the tagline from the Lay’s potato chip jingle: “No one can eat just one!” Lay’s’ marketing campaign ran successfully for years because it carried a deep truth: The chips are eminently enjoyable, even addictive. Eating them involves a nonstop cycle—hand to bag to mouth—that repeats until the bag holds only air. At least that’s been my Lay’s experience.

The chips’ addictive character did not emerge from Lay’s skill in finding exceptionally tasty potatoes. Instead, Lay’s engineered addictiveness into the product. Salt and fat in the right amounts, enhanced by the most satisfying crunchiness. Voila! Consumers were hooked. One study says alterations like Lay’s’ can make products as addictive as hard drugs.

Of course, Lay’s is not alone in engineering food. Food companies of all kinds manipulate their edibles to enhance taste, lengthen shelf life, or lower costs. So widespread and successful is the practice that such “ultra-processed foods” now account for more than half of all calories consumed by Americans.

But ultra-processed foods are making Americans and others progressively sicker. They are a great example of how a slavish devotion to growth generates a host of damaging side effects—in this case, many dimensions of poor health. Connecting ultra-processed foods, deteriorating public health, and profit-driven growth is surprisingly easy.

We Are What We Eat

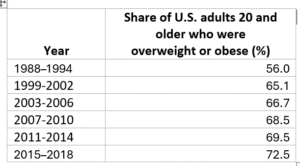

It’s a commonplace observation that Americans, broadly speaking, are in poor physical shape, and have been for decades. Thirty years ago, 56 percent of Americans over the age of 20 were overweight or obese. The share surged to more than 72 percent by the 2015–2018 period. Where data exists for the period since 2018, it shows a continued upward trend. This trend describes the weight of men, women, and children alike.

Growth we don’t want. (CDC)

Other measures of public health align with measures of overweight. A 2018 study revealed that only about 12 percent of Americans have “optimal metabolic health.” This means they score well, without the help of drugs, on measures of blood glucose, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, blood pressure, and weight circumference. The remainder of the population, nearly 90 percent of Americans, are below standard in one or more of these measures, putting them at increased risk of Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other serious health conditions.

Several factors lie behind the poor health of many Americans, including sedentary lifestyles, poor sleep, and high levels of stress. But diets high in sugar and fat are a leading cause. A new way of categorizing food, proposed by Brazilian nutrition researcher Carlos Monteiro in 2010, highlights the pervasiveness of these nutritionally subpar foods in diets worldwide. It also opens the door to a new understanding of the health effects of food. And it creates a framework for understanding the role corporations play in promoting foods that are literally killing us.

A New Take on Nutrition

The new framework, called NOVA (Portuguese for “new” and referring to the new categorization), divides foods into four groups based on the amount of processing involved in each.

Can you spot the NOVA1 segments? NOVA4? (Pablo Merchan Montes, Unsplash)

For much of human history we ate minimally processed “NOVA1” foods. These are whole foods such as fruits and vegetables, nuts, and meats that are unaltered or only slightly altered during cleaning or fermenting, or in the modern era, via packaging. NOVA2 foods are “culinary ingredients” like starches, oils, sugar, and fats; they are derived from the NOVA1 foods. NOVA 3 comprises processed foods that cultures worldwide have created by combining culinary ingredients (NOVA2) with unprocessed foods (NOVA1). These include freshly baked breads, cured meats, and in the industrial era, canned vegetables. So far, so good, nutritionally speaking.

The NOVA4 foods stand apart from the rest. These are “ultra-processed foods” or UPFs, the ready-to-eat, industrially formulated products that are made from processed substances such as oils, hydrogenated oils and fats, refined flours and starches, and variants of sugar. UPFs include pizza, nuggets and sticks, chips, cookies, candies, cereal bars, sugared drinks, and snack products of many kinds. Check the ingredients in UPFs and you’re likely to find unpronounceable words like polydimethylsiloxane, azodicarbonamide, and ly-cysteine. Monteiro, the nutrition researcher, writes that NOVA4 foods are “formulated to be intensely palatable and to fool the body’s appetite control mechanisms.” They are “fakes, made to look and taste like wholesome food.” They typically require little or no preparation by consumers, making them especially convenient. And they have long shelf lives, an advantage for manufacturers, who can worry less about storage and shipping times.

UPFs’ appeal for consumers and manufacturers leads food corporations to market them aggressively, via ads but also through strategies like reduced price rates for oversized servings. In the process, UPFs displace fresh or minimally processed foods—in a big way. A 2016 study found that UPFs accounted for about 58 percent of Americans’ energy intake and for nearly 90 percent of their consumption of added sugar. Put differently, more than half of our calories come from foods that people in 1900 would not have recognized.

Of course, Americans are not the only consumers affected. Sales of ultra-processed foods and beverages are ballooning worldwide, with the fastest increases now found among middle-income nations. In upper-middle-income nations, sales of UPFs projected for 2024 are 70 percent greater than in 2006. In lower-middle-income nations, the projected sales increase is 155 percent for the same period.

UPFs and Health

Ultra-processed foods are increasingly linked to poor health. A study published in Cell Metabolism in 2019 compared the eating patterns of 20 participants over two-week stints consuming processed foods and ultra-processed foods. The meals across the two diets had identical levels of total available calories, fat, carbohydrates, protein, fiber, sugars, and sodium. But participants could eat as much as they wanted. Thus, the study was a test of the hypothesis that UPFs drive people to eat more.

On the ultra-processed diet, participants increased their consumption of fats and carbohydrates, while consuming the same amount of protein as on the non-UPF diet. They consumed about 500 more calories per day and gained an average of two pounds compared to the alternative diet. By contrast, they lost two pounds on the non-UPF diet.

Other studies have shown that ultraprocessed foods are associated with type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all-cause mortality. Researcher Monteiro cites several studies of the UPF-health connection. Then he concludes, “…these studies document exponential growth in production and consumption of ultra-processed products; confirm that they displace unprocessed or minimally processed foods and freshly prepared dishes and meals made from these foods; document their aggressive marketing; and show their huge negative impact on the quality of diets and on obesity, metabolic syndrome and blood lipid profiles.”

In other words, they describe nothing less than a dietary revolution compared to the eating habits of a few generations back.

Corporate Culpability

Because of the health impact of these foods (along with alcohol and tobacco), authors writing in The Lancet, a leading British journal on health and medicine, concluded in 2013 that transnational corporations are “major drivers” of global epidemics of noncommunicable disease. Noncommunicable diseases are conditions such as heart disease, cancer, chronic respiratory disease, and diabetes that, according to the Centers for Disease Control, are the leading causes of death worldwide and constitute a growing threat to public health.

Pause and take that in. Food, alcohol, and tobacco corporations are responsible for driving the leading causes of death worldwide. How can this be?

The NOVA food processing framework suggests a strong hypothesis. Ultra-processed foods are high in salt, sugar, or preservatives—but also in profitability. This is because UPFs are cheaper to mass produce, store, and ship than unprocessed foods. In fact, major sellers of UPF foods, including Kraft, General Mills, and Nestlé, boasted average profits of 17 percent in the five years after 2018. But purveyors of basic foods like meat averaged just 6 percent over the same period. The more “value” added, it seems, the greater the corporate returns, public health be damned.

NOVA1 foods are harder to preserve and ship, a headache for food corporations. (CongerDesign, Pixabay)

In fact, switching out of UPFs could be painful for many firms. The Wall Street Journal reports that if the UPF share of Americans’ diets fell slightly, from 58 percent of calories to 47 percent, the corporations supplying food would see a seven percent decline in sales. And if Americans adopted the eating habits of Italians, who tend to avoid UPFs, “food companies’ business would crater.”

So food companies have a strong incentive to lasso consumers with their UPFs. To this end, UPF food corporations work to influence the 268 professional associations and other interest groups who offer dietary advice to consumers. A 2024 study found that Nestle belonged to 171 of these groups; Coca-Cola, to 147; Unilever, 142; PepsiCo, 138; and Danone, 113.

Corporate influence is none too subtle. In 2009, Coca-Cola granted $3.6 million to the American Academy of Family Physicians for advice on consumer education on beverages. Coke also gave the American Academy of Pediatrics nearly $3 million.

Meanwhile, food and beverage corporations, including Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and General Mills have fostered close ties with the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND). A 2022 study found a revolving door between AND’s board of directors and food corporations, as well as corporate funding of AND and its foundation (ANDF). For example, corporate contributions and sponsorships provided two-thirds of the ANDF budget between 2011 and 2015. Corporations also financed the research of nutritionists and weighed in on AND position papers on nutrition.

The story of food corporations’ promotion of UPFs bears a remarkable resemblance to tobacco firms’ infamous promotion of smoking. Both industries engineered addiction into their products. Each used sophisticated marketing strategies. Both engaged in arguably unethical targeting of children. And both worked to co-opt associations whose purpose was to promote health. For food and tobacco alike, the potential for profit was as hard to resist as a Lay’s potato chip.

The Growth Connection

The overriding policy goal of economic growth tends to keep the political system biased toward a careless brand of capitalism. It prevents a constitutional democracy from setting appropriate boundaries around the economy. It narrows the space available for regulatory policy.

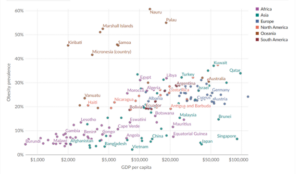

Zoom out from the food industry to the economy to see the intertwined advance of GDP per capita and obesity. In general, obesity is correlated with GDP per capita. Causality is more complicated than simply having more money to spend on food, though. The high profitability and therefore corporate favoring of UPFs is part of the equation.

GDP per capita and obesity march upward together. (Our World in Data)

The precise causal mechanisms underlying the obesity-GDP per capita relationship remain to be disentangled. But outlier cases of obesity, such as those found in the Pacific Islander nations, can shed light on some of those mechanisms. Why do these nations have higher rates of obesity relative to GDP per capita? Why do they account for nine of the ten nations with the greatest prevalence of obesity in the world?

Since the 1980s, the Pacific Islander nations facing globalization pressures have adopted international trade and investment agreements that often conflict with their preferred nutrition policies. This “regulatory chill” occurs when other governments use provisions under the World Trade Organisation and other agreements to block national legislation on nutrition. One example is Tonga’s desire to ban imports of mutton, which is high in fat. New Zealand, a key trading partner, opposed the move. The result in these and similar situations is that Pacific Islander nations opened their economies to inexpensive imported food, including cheap UPFs. This is likely at least a partial explanation for the obesity found in these nations.

In sum, the connections among bad food, poor health, and reckless economic growth policy are strong, whether at the corporate level or at the level of national economies. It seems our society is addicted not merely to sugar, salt, and fat, but to an economic system whose appetite is insatiable.

Gary Gardner is Managing Editor at CASSE.

"Rappahannock County Courthouse" by taberandrew is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

"Rappahannock County Courthouse" by taberandrew is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Indeed, the cost of “growth at any cost” is pretty devastating – this time, it’s human health and well-being.

I read once that a key event in this sad saga was in the 1980s, when US tobacco company RJ Reynolds merged with food company Nabisco (they’ve since split). The big tobacco guys were very versed in A/B testing, where one would have a consumer who is already a smoker try two slightly different cigarettes – which one do you prefer? As with biological evolution, continuous micro-changes drove the emergence of ever more addictive cigarettes, including the addition of small amounts of ammonia, which apparently makes a cigarette really “hit the spot” for a smoker and of course, more addictive, and (yay!) increasing sales. Growth!

Sadly it’s not hard to see how A/B testing in food would lead to stuff that’s optimized to light up all the reward centers and triggers in our Neolithic era brains.

Something that has struck me for years is that when passing through rural areas of the Western US, which are generally on the poor side – I don’t mean to offend anyone, but “on average” I think that’s a true statement – the state of health among the people is quite bad. The state of *dental* health is even worse – the degree to which rural conservative communities have normalized tooth extraction as one of life’s passages is saddening. The amount of Orajel on store shelves in rural America is another sign that something is broken. When I see what people buy to eat – almost exclusively UPF’s, usually with staggering amounts of sugar – it’s not hard to figure out what’s causing this.

The people affected would be vastly better off savoring the flavor of fresh and locally grown foods, and fresh baked breads (can’t beat the aroma). Ideally policymakers would be paying attention to charts of average population lipid levels and caries incidence, not average earnings per share for food conglomerates.

Thanks, Cole. Yes, it’s the corporate intentionality of it all that galls me. I try to imagine how the marketing meetings at Big Food, Inc. go as staff discuss how to “engage” more consumers more deeply. Do health reports ever enter those conversations? Surely those reports are known to the meetings’ principals. I can only conclude that rationalization ranks among humans’ greatest superpowers!

I echo Cole’s commentary; love the reference to fresh baked bread. We have 3 bakeries within walking distance. The “within walking distance” seems to be the other part of the formula for poor health. The GDP economy, embracing automobile culture, has made communities unwalkable, zoning commerce beyond walking distance. Thus, after “dining” on fried fast food, instead of going out for a stroll in unwalkable streets, the family sits down with potato chips to watch Netflix. Re Gary’s reference to obesity in South Pacific island nations, research by JMIR publications, passed on to us through the NIH shows that “A major factor to the rising prevalence [of adolescent obesity] is an insufficient amount of daily moderate-to-vigorous activity”. The rising temperatures of climate change will also contrinute to the phenomenon. In Kuwait, for example, a 42% obesity rate comes from a potent combination: it’s too hot to get out there and walk, and Gulf countries are invaded by air-conditioned fast food “restaurants”. My point is that poor, GDP- peddled NOVA4 foods and lack of purposeful exercise are inextricably related.

Thanks, Mark. Spoken like the avid cyclist you are! I often wonder why we Americans love the charm of European living–with those bakeries and patisseries on every block–but cannot imagine living that way, preferring instead the lifestyle of sprawl. Yes, building exercise into daily routines is another component to healthy living!

Even bicycling/walking advocates recognize that diet plays a larger share in obesity than physical activity but that the two are inseparable factors. I throw in a third factor. Places with poorer public transportation in the USA have higher obesity rates. “A single point increase in mass-transit ridership is associated with 0.473 percentage point lower obesity rate in counties across the USA.” Source: 2019 study by U of Illinois College of Engineering in Science Daily.

Terrific article.

It seems obvious that if a corporation is looking for, say, 7 to 10% returns, and inflation is to be kept at 2-3%, something’s gotta give to account for the difference (shrink-flation helps).

If you found this article useful, you might enjoy a whole book on the topic; one which I’m slowly making my way through:

The Commercial Determinants of Health.

https://academic.oup.com/book/44473

Thanks, Ken, and I appreciate the referral to the book. I’ll give it a look!

Gary

“Non contageous disease”? Yeah, obesity is contageous. Advertising is viral, targeted advertising is custom-viral, and use of social media is like eating without washing your hands.

I’ve been challenging myself to simulate diet in a post carbon future. Impossible, but I try. Grow what we can ourselves. Buy as much “locally” grown as possible, although “local” here seems to mean within a 70 mile radius! (Somewhere between half a day to an all day trip by a pair of horses pulling a loaded wagon, and requiring a change of horses for the return trip if that’s the next day.)

For things that can’t even meet that definition of local, I look for the highest nourishment density per unit of volume or of weight, with a long enough shelf life to put on a sailboat or horse-drawn wagon. Might come in plastic today but could come in paper or burlap sacks. Flour, dried grains, seeds, and legumes, dried pasta (especially spaghetti or soba noodles), papadams, and dried spices. Things that either I could buy twice, three times, or four times a year.

I got whole, unhulled chana dal – Indian chickpeas – to sprout. I ate the sprouted chickpeas but saved a few to plant. They’re growing nicely. I’ll have to try the same with mung beans.

Now I spend far more time in the kitchen, cooking, ending up with surprisingly little food for all the time spent, and struggling to stop losing weight. A lot more like pre-industrial life, except I don’t also have to tend a hearth or haul water every day.

Thanks, Robin. I’ve had a similar experience with a (very small) vegetable garden. Lots of care and effort, followed by feast or famine output, then dormancy. Let’s just say that production fell short of three-meals-a-day demand—by a long shot. I have yet to tackle the canning skills I’ll need. Or the carpentry. Or the electrical. Or the plumbing… My to-learn list is long, and time may be short! Thanks for your inspiration…