San Jose: An Information Economy Giant with Whopping Footprints

by Alix Underwood

What is your reaction when you hear the tagline “city with the highest GDP per capita in the United States”? Perhaps you would like to live in that city. Perhaps you think it sets a positive example for other cities. If so, you are not alone. Corporate and political leaders have been prioritizing economic growth for decades, and this mindset has trickled down until it has saturated the public.

The problem is that there is a fundamental conflict between economic growth and environmental protection. Real gross domestic product (GDP), a measure of the goods and services produced in a given polity, is causally associated with various measures of environmental impact. In many cases, it is also associated with negative social outcomes, such as inequality. Therefore, cities with huge economies are unwieldy giants, trampling planetary boundaries with their ecological footprints.

Cities account for over 80 percent of our $105 trillion gross world product (GWP). Some of these economic giants tower over the rest. New York-Newark-Jersey City had the world’s biggest metropolitan economy in 2022, with a real GDP (chained to 2017) of $1.87 trillion. That’s over two percent of 2022 GWP and leagues larger than the next-biggest metro economy, Tokyo.

To fairly judge the sustainability of these giants, however, we must acknowledge the vast populations they support. Over half of humanity lives in urban areas, and the UN projects an increase to 68 percent by 2050. Per capita metrics are most appropriate for considering the equitable distribution of our planet’s finite resources. Few rival the United States in terms of ecological footprint per capita, so let us consider the most unwieldy U.S. city economy.

The Most Unwieldy Giant

A whopping 90% of the United States’ $21.8 trillion economy in 2022 was attributed to metro areas. Consider again the New York metro, home to around 19.5 million individuals, far more than any other U.S. city. Its real GDP per capita, adjusted for cost of living, was $84,564 in 2022. That’s nothing to sneeze at, but it landed New York in tenth place amongst its U.S. counterparts with populations over one million.

The United States’ third most unwieldy giant in 2022, with an adjusted real GDP per capita of almost $92 thousand, was the Boston metro. The San Francisco metro took second place, at over $120 thousand. And the “winner,” with the most unwieldy economy by far, was…drum roll, please…the San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara metro, at $171,660.

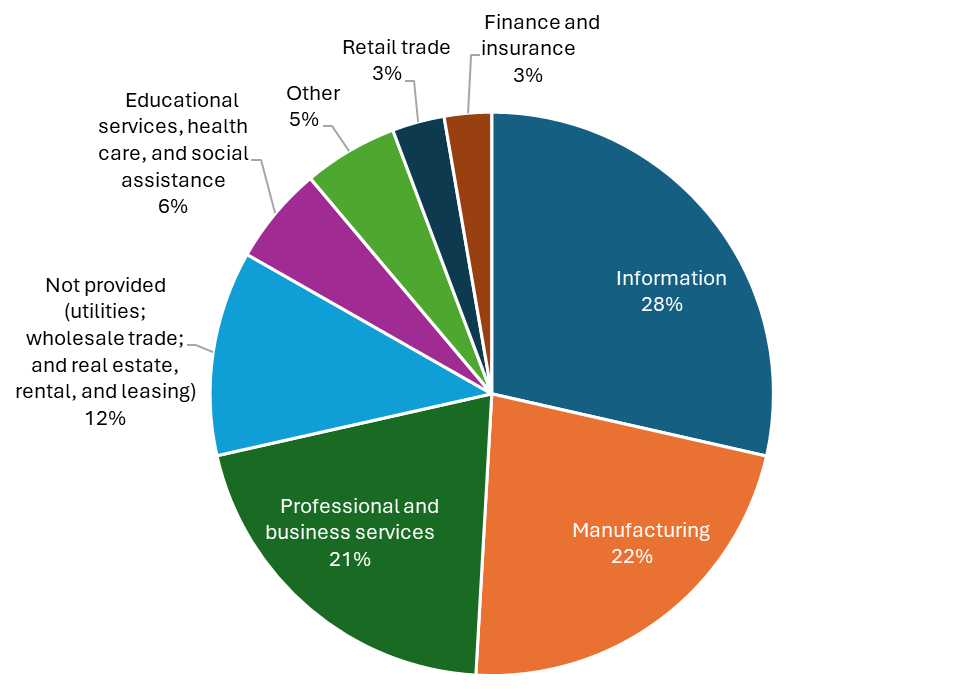

San Jose metro’s real GDP by industry. Figure created using data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

That was over 15 times the GWP per capita! San Jose may be a nice place to live for those who benefit from its economy. However, the rest of the world has the right to be outraged by this overproduction/consumption.

Let’s consider the parts that compose San Jose’s unwieldy whole. Services-producing (as opposed to goods-producing) industries account for over three-fourths of San Jose’s GDP. 28% is attributed to “information” industries, which include data processing, telecommunications, and software publishing, to name a few. It is no surprise that information technology dominates the economy of a city dubbed the Capital of Silicon Valley.

The Footprints of an Information Giant

Many believe the information economy is the key to “decoupling” economic growth from natural resource extraction, and thus environmental impact. On the surface, it appears that San Jose, with its giant information economy, has taken strides toward decoupling. WalletHub ranked San Jose the sixth “greenest” U.S. city, largely due to its shift toward renewable energy sources. WalletHub needs a lesson in the trophic structure of the economy.

All economic activity, be it mining for metals or data, rests on a foundation of agriculture and other extractive industries. Therefore, all economic activity has environmental impacts. There would be no demand for information services without a surplus in the physical goods we rely on: food, water, shelter, clothing… electricity, transportation, internet, data centers. We rely on more goods (and more complex goods) the further up the economic pyramid we go.

Services-producing industries exist throughout the trophic structure of the economy. Information industries are at the top of the pyramid, as they consume materials and energy from all of the other trophic levels.

The apparent compatibility of San Jose’s unwieldy economy and local environmental progress is just that: local. If we broadened our scope, we would find this giant’s footprints stamped upon the Earth far and wide. Some of these footprints can be identified via environmentally extended input-output analysis (EEIOA). For a robust EEIOA, a researcher would examine the impacts of the intermediate inputs used by the city’s industries, the impacts of the inputs used by those industries, and so forth.

For a more nuanced approach, a researcher would also consider how the city’s economic outputs are used. Customers often use information services to produce and consume more goods and services. Think of all the information and technology used by the fossil fuel industry, for example, to extract and sell more fossil fuels.

For an even more nuanced approach, a researcher would consider the destinations of the dollars flowing through the city’s economy. How do San Jose’s residents—most notably, its ultra-rich residents—spend their money, and what’s the environmental impact? Here, I scrape the surface of such an analysis.

Direct Footprints: Information Inputs

Unfortunately, the Bureau of Economic Analysis does not provide input-output data at the metro level. However, national accounts paint an overall picture, which we can roughly apply to San Jose. In 2017, U.S. information industries spent $750 billion on intermediate inputs. 12%, or $90 billion, went toward manufactured goods.

However, information industries spent most of the $750 billion on other services. Many of these services (for example, real estate, which accounts for $60 billion) rely inherently on physical goods and infrastructure. They might be better termed “gervices.”

Refocusing on San Jose, the city’s biggest information firms provide another lead. Excluding local government and universities, the top three employers in San Jose are Cisco Systems, Kaiser Permanente, and Adobe Systems, followed by the likes of Western Digital, Broadcom, and PayPal. Except for Kaiser Permanente, these are all technology companies, as expected of Silicon Valley.

Headquartered in San Jose, Cisco is a communications technology service provider that obtained $57 billion in revenue in 2023. Over three-quarters of this revenue comes from what Cisco dubs products, as opposed to services. These products include switching, routing, and video distribution; processes that most of us consider (if we consider them at all) the metaphysical results of software engineering magic. However, they require very real, physical hardware, infrastructure, and energy.

A China National Petroleum Corporation data center (Charlie fong, Wikimedia).

The necessary hardware comprises silicon and various metals and rare earth elements. Data centers store and process the information that flows through cabling to reach Cisco hardware. These huge facilities are under scrutiny for their material- and water-intensity, though we don’t know just how much they consume, due to a lack of regulation. Cisco owned 16 data centers as of 2021.

The stimulant that brings this hardware and infrastructure to life is energy, especially via copious amounts of fossil fuels. Greenhouse gas emissions from information and communication technologies rose from 2.5% of global emissions in 2013 to 3.5% in 2019. To put that in perspective, commercial flights account for about 2.4% of global emissions.

Indirect Footprints: Dollar Destinations

The net earnings of information firms in San Jose go toward rent, wages, interest, and profits. Companies pay rent for land and property; physical resources. As for wages, interest, and profits, we can be sure San Jose’s information employees, stockholders, and C-suite executives use much of that money to buy tangible goods with tangible environmental impacts.

I am not criticizing the high number (7,500) of individuals that Cisco employs in San Jose. I would prefer to highlight the company with the highest revenue, as opposed to the highest employment, but I could not find that information. Everyone willing and able to work should be employed with an equitable and sustainable wage. There’s the rub: Cisco’s $36 billion in gross profit (revenue minus cost of intermediate inputs) is not distributed equitably or sustainably amongst its employees.

For those San Jose residents fortunate enough to have full-time, permanent employment at Cisco, average salaries are high by most standards. For example, business analysts make around $94,000 and product managers around $176,000. This pales in comparison, however, to the $23 million going annually to Cisco’s CEO, Charles (Chuck) Robbins, whose estimated net worth is over $148 million.

Chuck Robbins (center) at the Business Executives for National Security annual gala in 2018 (Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Flickr).

To be fair, Robbins’s annual pay is much lower than that of Broadcom’s (also headquartered in the San Jose metro) CEO, Hock Tan, which amounts to $161.8 million. Hock Tan is the highest-paid CEO in the United States. The second-highest-paid CEO, Nikesh Arora, also works for a San Jose-based company, Palo Alto Networks. In fact, five of the ten highest-paid CEOs in the United States are based in the San Jose metro (a sixth is based in San Francisco).

San Jose has plenty of billionaires to keep these CEOs company: 68 to be exact. That’s more than any other city in the United States. Some of these billionaires likely benefitted from the $10.6 billion that Cisco returned to its stockholders in 2023.

A City, and a Planet, for the One Percent

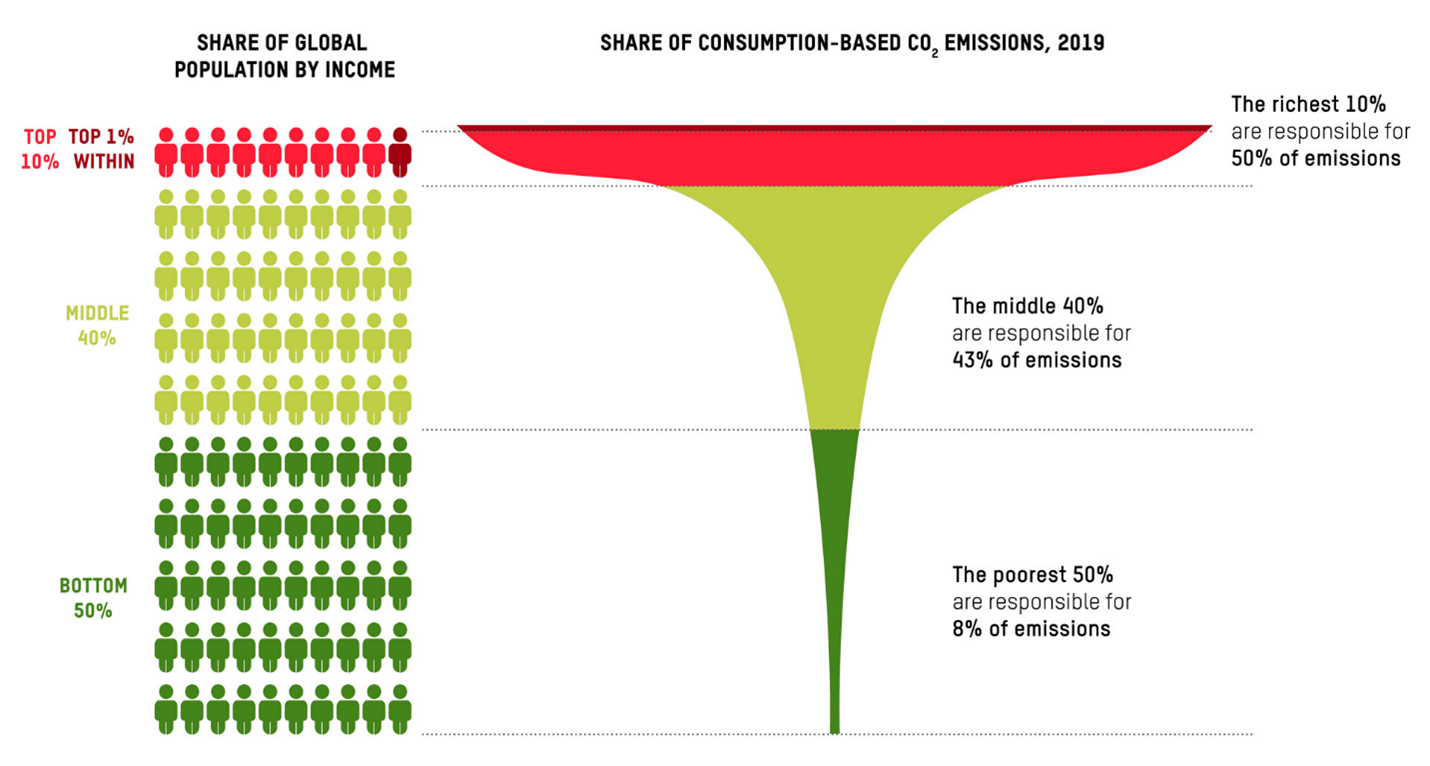

If you think the amount of money someone has doesn’t correspond to their ecological footprint, think again. An Oxfam analysis revealed that, in 2019, the world’s richest 1% generated 16% of global carbon emissions. This was equivalent to the emissions of the world’s poorest 66%. Cisco’s CEO falls squarely into not just the top 1%, but into the top 0.01% in the United States.

Figure from a 2023 Oxfam report titled Climate Equality – A Planet for the 99%. (The material “Climate Equality: A Planet for the 99% – Khalfan, Ashfaq, Nilsson Lewis, Astrid, Aguilar, Carlos, Lawson, Max, Jayoussi, Safa, Persson, Jacqueline, Dabi, Nafkote, Acharya, Sunil – OI – November 2023 – (Figure on pg. xi)” is reproduced with the permission of Oxfam, Oxfam House, John Smith Drive, Cowley, Oxford OX4 2JY, UK www.oxfam.org.uk. Oxfam does not necessarily endorse any text or activities that accompany the materials.)

Therefore, the irony abounds in Robbins’s CNN Business article titled “10% of the world lives on $2 a day. It’s time for businesses to step up.” He calls for “inclusive growth,” citing the objectives of “business growth and enhanced consumer purchasing power,” goals “we all believe in.” Robbins highlights Cisco’s cash donation to San Jose’s Destination: Home. This donation is much smaller than Robbins’s net worth.

Speaking of Destination: Home, San Jose has the fourth highest number of houseless individuals per capita in the United States. The connections between extreme wealth and extreme poverty in the San Jose metro are complex. Suffice it to say that a high GDP per capita does not translate to prosperity for all.

If “highest GDP per capita in the country” sounded like a good reason to move to San Jose when you started reading, hopefully this article has given you pause. Is that something to covet, to strive for? Or is it something to be ashamed of, on the national and especially the global stage? For a truly sustainable economy, even the middle class in wealthy countries will need to adjust their lifestyle expectations. As a member of that demographic, I’m not sure we’re ready to point the finger stridently at ourselves; not with San Jose billionaires on the loose.

If we tackle the most extreme wealth first, the U.S. middle class will eventually become the new extreme. It’s an uncomfortable thought, but as we are relational and adaptable beings, a shift in what we consider socially acceptable will affect tangible change. The necessary lifestyle changes will transform from overwhelming and unrealistic to natural and expected.

If our social circles—including the people we appreciate and admire—believe it is unacceptable to own two cars, we will be content with one. If we believe it is unacceptable for our city’s GDP per capita to exceed $100,000, we will expect our local government to enact steady-state policies. We will use our political voice and vote accordingly. If we believe it is unacceptable for a CEO’s salary to exceed $10 million, we will support a Salary Cap Act. We’ll also do our part to use fewer—or even earn fewer—dollars in the first place.

Alix Underwood is a Research Associate at CASSE.

Nice analysis. I am literally a child of the Silicon Valley, born in Stanford Hospital and grew up in Palo Alto, Menlo Park, and Mountain View.

There is so much I could comment on, but the main thing that comes to mind is how Silicon Valley (and its “capital”, San Jose) has lost its way with regard to what it should be doing. In the beginning, and what I remember, was that the valley was full of scientists and engineers pushing the boundaries of knowledge and technology. Now, that is obviously not very steady state right there, but one can sort of see the attraction and with some shifts in resource pricing and allocation, it could be so even now.

Sometime I think in the late 1980s this began to shift, when it became clear that a great deal of *money* could be had in the course of developing new technology. I have to say that Bill Gates and Microsoft were probably key influences here. Instead of seeing money as frequently correlated with new technology, Gates and Microsoft made the pursuit of money the center of it all.

Alas, by the late 1990s a sort of “finance bro” culture had firmly taken root. Everyone was obsessed with stock options and conspicuous consumption. I remember at the time thinking it was weird and undesirable, and unseemly. The engineers and scientists I remember from my youth, who were proud of their achievements in the Apollo project and beyond, were also perplexed. Get rich working in tech? One could reasonably expect a comfortable middle class salary, building navigation and propulsion systems for moon rockets and the like, sure, but rich? No way.

We shall see what happens. As Alix notes, we can’t go on this way. San Jose and the region is not very pleasant to exist in today, to be quite honest. I no longer live there but when I go back, I’m saddened. Hopefully the valley can find a constructive role creating the technology needed to assist humanity in a transition to a steady state on our only habitable planet.

Thanks, Cole, for this much-needed local perspective. I decided to write about whichever metro had the highest GDP per capita, which happened to be San Jose, an area with which I have no personal experience. So, I couldn’t speak to local cultures or the motivations of the (I’m sure brilliant) minds driving San Jose’s info economy. Interesting to hear from you how there’s been an unfortunate shift in priorities.

I just re-read your excellent article, and two other thoughts bubbled up that seemed worth sharing:

– Since I do have a local perspective on San Jose and the Silicon Valley (finally! after all these articles on the Herald about places I have not lived in, lol) I can share that the culture there venerates “being smart” with the same anxiousness that some cultures put a lot of value on, say, machismo. There are an awful lot of people in San Jose/the Valley telling themselves, and each other, that they are brilliant. It is true that one will find a somewhat higher density of gifted individuals than most areas of the US or the world. But – trust me on this – there are plenty of ordinary or even rather foolish people, sometimes doing surprisingly well. I will give just one example (of dozens I could list) that is easy to understand: Mark Zuckerberg’s insistence that everyone in the world would surely want to wear virtual reality goggles all day long. And therefore, the right thing to do is spend $20 billion trying to shape that world. What that $20 billion might have done for the planet .. sigh.

What I can also share is that over my years there, I’d say quite a lot of the true technical geniuses share a lot in common with steady state thinking. There seems to be a pattern where the most remarkable individuals gradually shift from being “smart” to being “wise”, and often seem to take stock of it all and conclude: this is not going to end well for humanity. This does not always happen, but I’ve seen it happen a lot.

– Shifting gears: you’re spot on with regards to the US middle class becoming potentially the new extreme. On the hopeful side with that, I can point out that the a US middle class household has way, way too much stuff. So much stuff that it is making people miserable. I’d assert that most middle class people in the US are borderline hoarders. Less material stuff, more thoughtfully acquired, will be a boon to happiness.

Thanks for these additional insights, Cole!

I used to live in Silicon Valley. San Jose in the 80’s and early 90’s, Los Altos in the late 90’s and the aughts. Like Cole Thompson, I also observed a shift from the sheer joy of playing with tech toys to the focus on money, also with consternation.

Relative to most of the rest of the world, middle class America is also filthy rich.

We need a Court and Legal system that is willing to remove personhood from corporations. Better yet, eliminate public corporations entirely. Get money out of politics. Disallow private counsel in courtrooms – require all counsel to be public.

Only then can we begin to tackle the obscenity of the billionnaires and hundred-millionnaires.

Thanks for this comment, Robin. Great to get more local perspectives! And I agree with your legal/political assessment.

It is good to note exceptions to the economic growth mindset that is awash in the tech sector.

Justin Rosenstein inventor of the Facebook like button is a founder at oneproject.org. Some of his tech growth money being used to look for an alternative sustainable ideology at oneproject.org.

Good point; I’m sure there are many exceptions. I had never heard of oneproject.org. Thanks for sharing!

posting a little late to the party but want to make a general comment. What CASSE stands for is absolutely

on target, and getting the word out is high priority. I urge all who post approving or even disagreeing (or anything in-between) comments, to also buy the Daley books for redistribution to people they know and to also make suggestions to Brian on how they might facilitate specific interactions with target organizations.

Interactions to include things like debates or small face-to-face discussions. Not to forget ones own actions

like post card writing (you know what I mean!). Sincerely, Al