A Big Conservation Win for Benzie County

by Dave Rollo

Lake Michigan dunes, Benzie County, Michigan (credits: CASSE).

Benzie County lies at the base of the pinky on the “Mitt,” as Michiganders say, referring to their left hand as a convenient “map” of their state. The county is blessed with one of the largest deepwater harbors on Lake Michigan, Betsie Bay. It has long provided mariners with safe refuge from the fierce gales of Lake Michigan. Jetties protect the bay’s inlet, where a historic lighthouse has guided ships for over a century.

Betsie Bay is fed by the wild and scenic Betsie River, a state-designated Natural River. The river winds over 50 miles through forests, lakes, and wetlands. Paddlers and fishermen love the Betsie River, particularly during the fall salmon runs.

Benzie County’s western border is Lake Michigan coastline, featuring one of the most scenic dunescapes on earth. Particularly spectacular are the Sleeping Bear Dunes, some of which rise to 460 feet. The coastal town of Frankfort lies on the north side of Betsie Bay, just south of the Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore. The smaller village of Elberta is located on the opposite side of the bay.

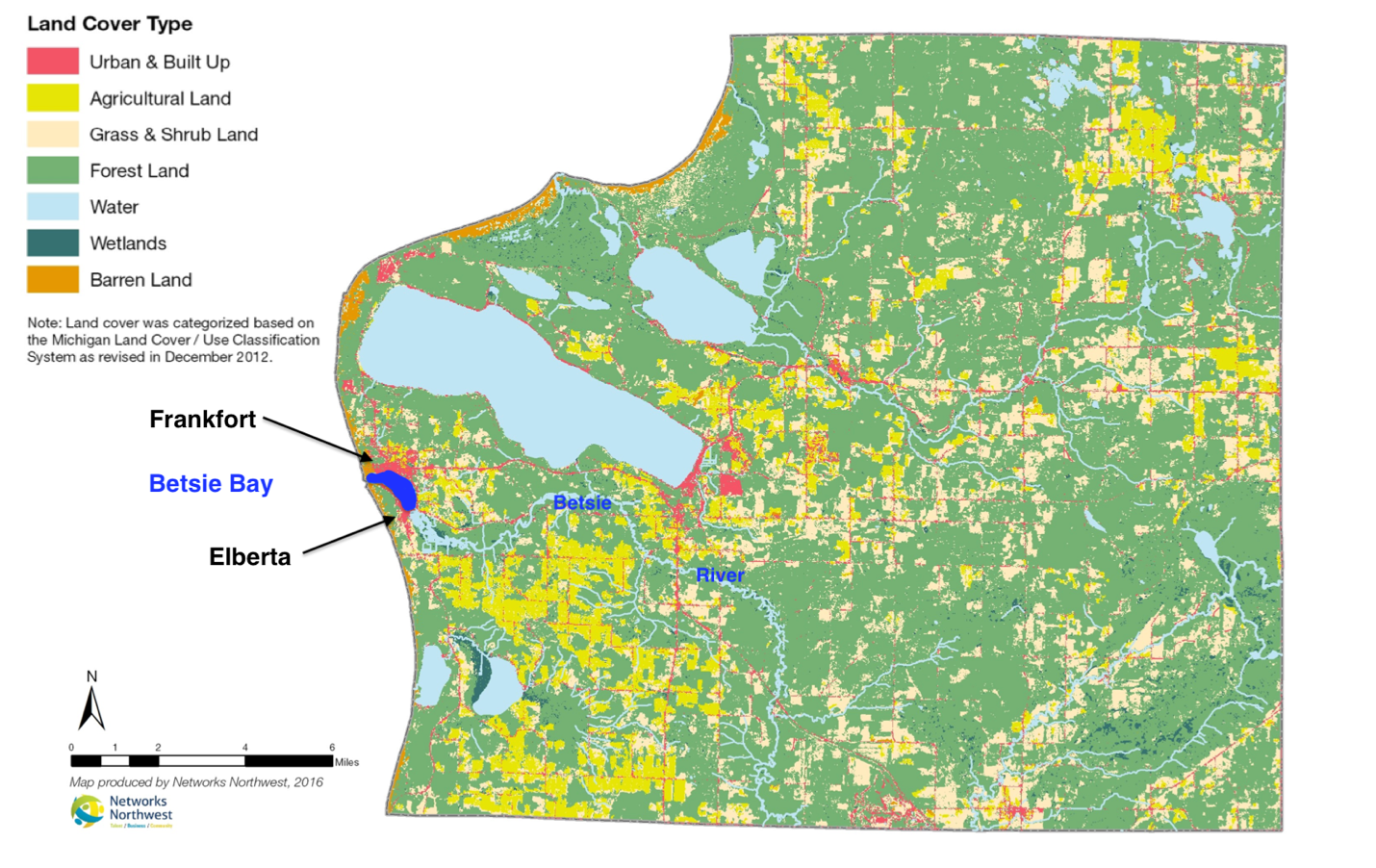

Benzie County is 67 percent forested. Nearly half of these forests are protected in federal and state ownership. The county has over 57 lakes and nearly 17 percent wetland cover (map by permission of Networks Northwest, derived from USGS Land Cover Dataset, 2016).

Frankfort is Benzie County’s largest municipality (and only town), with some 1300 residents. Elberta’s population is 315. Between Elberta and Lake Michigan lies a large tract of mostly undeveloped land. This includes a flat tract beside the water that was once used for industry, bordered to the south by 250-foot dunes of the Elberta Bluffs. This tract was a hub for commerce and lumber and iron-ore production in the late 19th century. Aside from a kiln for smelting iron—now resembling a medieval ruin—a switchyard occupied much of the tract’s shore. It had piers for offloading cargo and passengers. Tourists arrived to the north country via ships that anchored in the harbor. The last passenger and car ferry departed Elberta in 1978.

As the boom of timber and iron processing waned at the turn of the 20th century, the area became increasingly dependent on tourism. Today, Benzie County’s population more than doubles during the summer months. Much of the area’s commerce depends on these visitors. While Frankfort has developed a diverse economy relative to its size, with a restored historic theater, an art center, bakeries, restaurants, and the county’s largest employer, Graceland Fruit, Elberta remains the poor sister across the bay.

The vacant tract on Elberta’s shoreline that was once occupied by industry has been on the market for decades. All the while, Elberta’s residents have watched with apprehension. They hope that the area will be revitalized yet fear predatory investment that might change their village for the worse. In 2024, their fears materialized.

A “Jet Set Resort”

Likely due to tourism, land speculation, and post-COVID telecommuting, Benzie County land values have skyrocketed in the last decade; especially near Lake Michigan’s coast. Investment potential has incentivized speculation and priced many low-income residents out of the market.

In 2006, Elberta Land Holdings, LLC purchased the Elberta Bluffs property. They cleaned up the abandoned industrial area and marketed the land to potential buyers. The price of the property rose to $24 million. The land’s fate became a frequent topic of conversation among Elberta and Frankfort locals. They hoped for modest development that would preserve the area’s natural beauty.

Elberta Bluffs (top) as seen across Betsie Bay from the town of Frankfort. A rendering (bottom) depicting the scale of the resort development proposed in 2023 (credits: CASSE).

In 2021, Elberta Land Holdings granted Richard Knorr International (RKI) an option on the purchase of the land. RKI is a large, Chicago-based real estate development company specializing in oceanfront resorts. It has offices in numerous U.S. states, as well as in Argentina, Brazil, Panama, and Mexico. Its proposal, billed as economic revitalization, was a 400-unit, seven-story resort with condominiums, apartments, a hotel, and a marina with private yacht slips on Betsie Bay. All told, the massive structures would have occupied 3000 feet of shoreline on the bay and 300 feet on Lake Michigan.

One impediment stood in the way of the massive resort: a building height variance. As described by Glen Chown, director of the Grand Traverse Regional Land Conservancy (GTRLC), RKI’s vision was to cater to “jet set wealth.” Their target return on investment required structures of at least seven stories (70 feet), double the height allowances in the village zoning code. The Village Council would have to grant a height variance for RKI to complete the deal.

The state of Michigan considers Elberta a “financially distressed community.” About 10 percent of Benzie County’s population lives in poverty. RKI’s development proposal promised hundreds of jobs, although about 60 percent would have only lasted for the construction phase. The remainder would have been in facilities operations in the complex, including the hotel and marina.

RKI advertised the jobs and capital investment as an income and tax generator for the village. Yet the sheer scale of the development did not sit well with Elbertans. Neither did its marketing as a luxury retreat for the wealthy. Jim Barnes, a local eco-building contractor and founder of one of the area’s most-loved restaurants, said that almost no residents were in favor of the project, despite the economic and employment enticements.

Citizens for Elberta

Soon after RKI submitted the development proposal to the village government, a group of area residents known as Citizens for Elberta began alerting their neighbors to the project’s scale. A core group of volunteers canvassed to spread the word, and skepticism quickly emerged throughout Elberta and Frankfort.

Jim Barnes took on the role of an intermediary for a better outcome. He reached out to RKI to arrange a meeting with local citizens. Barnes did not aim to oppose the developer outright but rather hoped that “breaking bread with the local residents” would convince RKI that the project’s scale was inappropriate. RKI did not accept the invitation. Jim Barnes and a core group of three activists (including, fortuitously, a member of Elberta’s planning commission) also built a relationship with the seller, the Elberta Land Holding Company. Barnes believed that “the community can actualize something better.”

The activists also engaged about 150 people in Elberta and Frankfort to voice their concerns. Responding to the popular outcry, the Elberta Planning Commission enacted a moratorium on development, which proved decisive. As the option to purchase was only six months in duration, RKI withdrew its offer. Citizens for Elberta was successful…for the time being.

Fearing another offer would come quickly, Citizens for Elberta offered to assist the holding company in finding another buyer. They aimed to identify a buyer in alignment with the village’s conservation ethic and sense of place.

A Community-Derived Outcome

A development community insider was also alarmed by the scale of the resort proposal and alerted Glen Chown at the GTRLC. The Michigan Chapter of the Nature Conservancy was tipped off, too. Both conservancies have fought to protect key areas of the upper Michigan coastline for decades. However, the purchase price of the Elberta land seemed prohibitive.

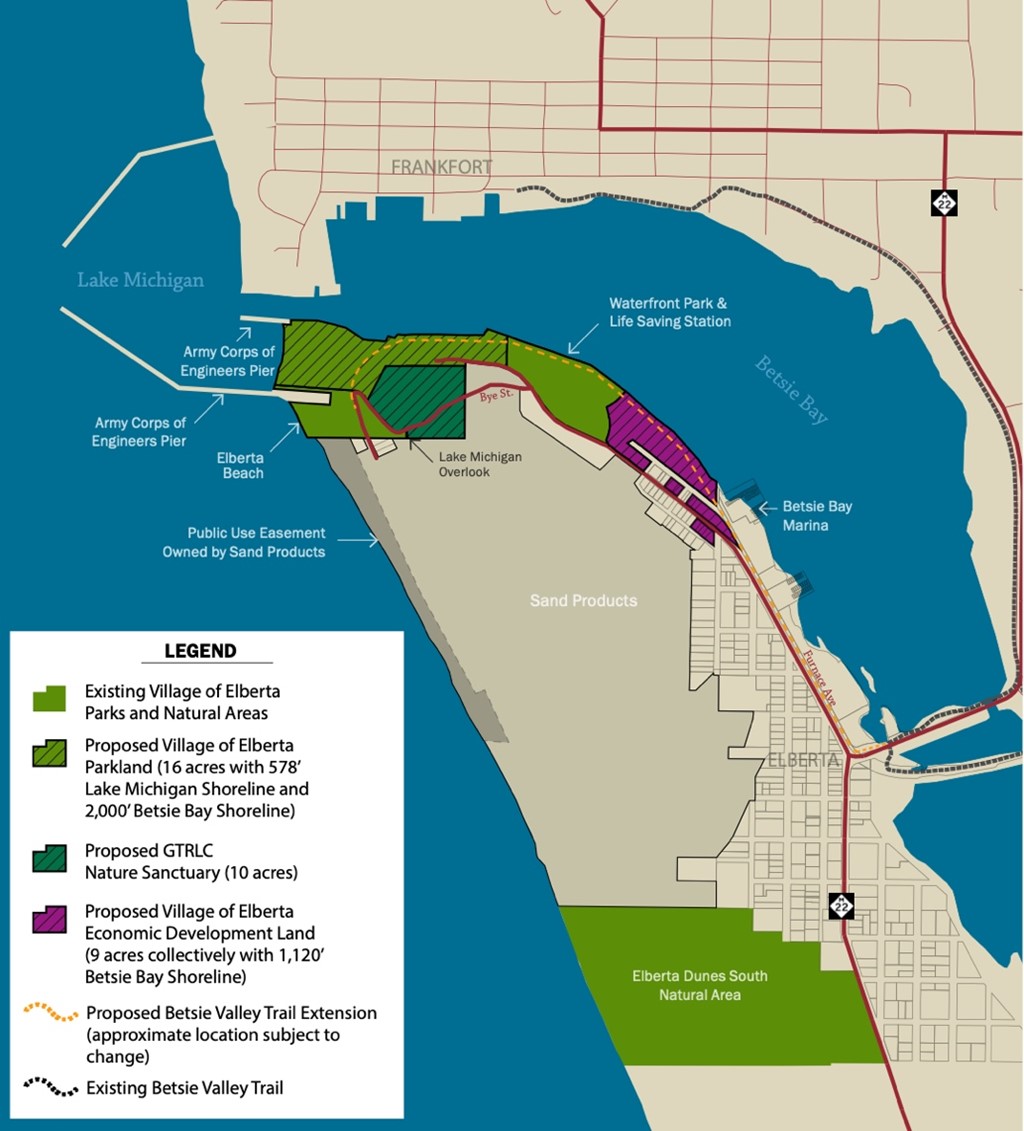

Jim Barnes and the Citizens for Elberta worked to bring the land conservancies and the holding company together. “Instead of real estate agents as intermediaries, we sought to have the key leaders meet personally—and so we brought everyone together in Grand Rapids,” said Barnes. The meeting was successful, insofar as the holding company agreed to reduce the price of the Elberta land to $19.5 million. GTRLC took the lead on fundraising, but Elberta Land Holdings gave them the same time window as RKI: six months. The parties also arranged to develop nine of the thirty-five acres for Elberta’s economic and housing needs.

Conservation and development plan for the GTRLC purchase in Elberta (map courtesy of the GTRLC).

GRTLC has a history of success, moving to purchase less-expensive properties in only days. However, raising $19.5 million in a six-month window seemed improbable for the land conservancy. Propitiously, the improbable proved possible.

Glen Chown describes the effort: “We reached out to our supporters and to the Frankfort/Elberta community—the response was astonishing.” At the outset, an anonymous donor pledged a $9 million gift on condition that GRTLC raise the remaining $10.5 million in the allotted timeframe. “People stepped up and dug deep—we had contributions as low as seven bucks. Someone sent us their $20 winning lottery ticket.” All told, over 700 households pitched in. Many who contributed could not pledge a lump sum and so chose installments in monthly payments.

As the six months drew to a close, GTRLC was $4 million short of its goal. They used a bridge loan to make up the difference, and the purchase was finalized on Friday the 13th of December, 2024.

Next Steps

After fast-paced organizing against a pending mega-development, followed by the amazing feat of raising sufficient funds for purchasing the property, important work lies ahead. Jim Barnes describes the development of the nine acres adjacent to the village as “the best gift the Village of Elberta could ever wish for.” As part of this process, the not-for-profit land bank of the state of Michigan (the Michigan State Land Bank Authority) acquired the acreage. Josh Mills, Frankfort Superintendent, anticipates a mixed-use development. This would include live/work retail spaces, creating opportunities for commerce while providing much-needed workforce housing. Jen Wilkens, Elberta Village Council President, agrees: “A best outcome would be some missing middle housing, possibly a restaurant, a few shops, and a meeting place/historic center.” Currently, the search is on for a developer with a good track record of such projects.

This type of mixed-use development aligns with Elberta’s Master Plan. The plan points to a need for more housing types, particularly small, multifamily, and shared units. According to Jim Barnes, the master plan was fortuitously adopted in 2024, just in time to help guide the new addition to Elberta.

The 35-acre GTRLC purchase of Elberta’s scenic waterfront includes the ecologically sensitive Elberta Bluffs (photo courtesy of the GTRLC).

The GTRLC also has plans for the remaining 26 acres, which are to be preserved. It will transfer sixteen acres along the waterfront, including 3,120 feet on the bay and nearly 600 feet on Lake Michigan, to the village of Elberta for use as a park. Ten acres of the forested dunes will be protected as a nature sanctuary. The GTRLC is working on raising $8 million in additional funding for facilities. This will include a walking/biking trail extending along the harbor to the beach.

The conservancy’s long-term objective is to expand the preserve to connect the Elberta Bluffs to the Elberta Dunes South Natural Area. Michigan Sand Products owns a large tract of land between the two GTRLC properties. However, state law prohibits the sand-mining company from mining on this property, as it is regarded as critical dune habitat. Furthermore, the steep topography will likely limit residential development.

Prospects are bright for continued civic involvement that ensures the best outcomes for the community. The twin successes of rejecting the massive resort and permanently preserving Elberta Bluffs demonstrate a recurrent theme described by Glen Chown, Josh Mills, and Jim Barnes: a deep conservation ethic among citizens. A recent poll by the Benzie County Conservation District confirms this; the loss of natural areas and open space ranks as the number one concern for area stakeholders. The vigilance and civic participation of Benzie County residents illuminates a path for success in keeping counties great.

Dave Rollo is a policy specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

Dave Rollo is a policy specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

Its heartening to see democracy in action alongside pragmatic activists working to protect their local area from the wrong kind of development.

Too many areas of outstanding natural beauty have been turned into off season ghost villages when wealthy second homers want to own a holiday home. Locals then unable to afford to live where they come from while the community dies socially unable to support maybe a school. The pretty fishing villages no longer home the fishermen.

The unfortunate reality is that initially these purchasers, when young visited the area on family holidays in their cars, gaining an affinity for the pretty area. Then as time and economic growth passed by, they are now able to buy their second homes unaware of its impact both environmentally and on the community. It’s then this accumulation of second homes and development that often overdevelopes that area destroying the beauty that attracted everyone there in the first place.

In many areas there is ineffective democracy with power, lobbying and profit deciding the outcome.

Fortunately in this case there is an effective local democracy (the blow ins don’t have votes), along with those pragmatic activists ensuring a positive outcome.

So happy to read about a conservation success story which provides good benefits to local residents. Kudos to all involved. This was an uplifting read on a grey winter day here in Connecticut. You should submit the story to Positive News. It’s certainly worthy of that publications goals. https://www.positive.news/