A Primer on Economic Growth and Biodiversity for COP16

by Brian Czech

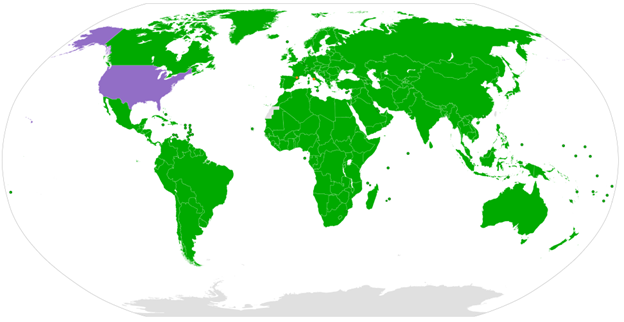

Why is the USA the only major non-party to the Convention on Biological Diversity? Because no other country is more obsessed with GDP growth (Redrobsche, Wikimedia).

With the core meetings of the United Nations Biodiversity Conference (COP16) starting next week, it’s time for a primer on the relationship between economic growth and biodiversity conservation. The last thing we want is a COP16 devoid of discussion about the conflict between growing the economy and conserving biodiversity. In fact, the “800-pound gorilla”—GDP growth—ought to be front and center.

Devoted Herald readers may feel a tinge of déjà vu, given a similar article for COP15 in Montreal. This one is updated, however, for COP16 in Cali, Colombia. Updates are primarily in the introductory and concluding segments. The guts of the piece are unchanged, because they are timeless and bear repeating.

For the uninitiated, the conference in Cali is called “COP16” because it is actually the 16th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP) to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. The original meeting was at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. The Conference of the Parties, then, is a vast international, bureaucratic structure that has taken on a lengthy life of its own, similar to that other “COP” structure on climate change, where COP28 was the recent iteration. (And yes, the “good COP bad COP” puns abound, although neither COP has been particularly effective.)

The goal of the parties at COP16 is to develop the strategies to achieve the 23 targets of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which was adopted at COP15. The framework gets its name from the fact that COP15 was chaired by China but, in the latter stages of the Covid pandemic, was hosted by Canada. The highlight of the framework is Target #3: the “30 by 30” goal of conserving 30% of lands and waters, for biodiversity purposes, by 2030.

My goal herein and at COP16 (including the panel I’m on) is to explicate and reiterate the overlooked, fundamental conflict between economic growth and biodiversity conservation. If the Global Biodiversity Framework is to have any chance of success, conferees must harbor no illusions of “green growth.” They must firmly grasp the reality that all the biodiversity conferencing in the world will amount to an exercise in futility as long as the overriding goal of the parties is GDP growth.

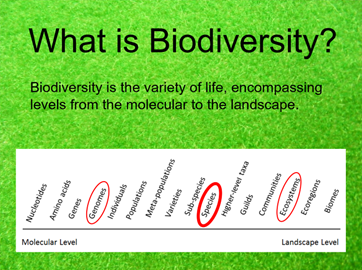

What is Biodiversity?

Biodiversity is the variety of life. To anyone with eyes or ears, biodiversity is beautiful, fascinating, and awe-inspiring. It accompanies the sacred—it is the sacred—in the hearts and minds of many. And for everyone, whether they know it or not, biodiversity is crucial for the functioning of healthy ecosystems that are capable of providing us with food, clothing, shelter, and a long list of ecosystem services. Economically, then, biodiversity is priceless.

Biodiversity is the variety of life. To anyone with eyes or ears, biodiversity is beautiful, fascinating, and awe-inspiring. It accompanies the sacred—it is the sacred—in the hearts and minds of many. And for everyone, whether they know it or not, biodiversity is crucial for the functioning of healthy ecosystems that are capable of providing us with food, clothing, shelter, and a long list of ecosystem services. Economically, then, biodiversity is priceless.

We usually think of biodiversity in terms of species, but it encompasses levels ranging from the molecular to the landscape. In other words, the biodiversity spectrum runs from the building blocks of life at one end to complex ecosystems at the other. Billions of organisms and millions of species occupy the middle stretch, but diversity manifests at all levels.

At the molecular level, genetic variance contributes to differences among members of the same species, allowing for natural selection and evolution. At the landscape level, ecological variance covers countless combinations and interactions among species. In fact, at the landscape level, geophysical features such as ice sheets, canyons, and ocean currents are interwoven with the life therein and thereon.

Biodiversity at all levels changes constantly due to factors including genetic mutation, the evolution of species, ecological interaction, weather and climate, geological forces, and astronomical events. Some of these changes are fairly predictable, while others are seemingly random or “stochastic.” For roughly four billion years, none of these changes were influenced by humans.

Prehistoric and Early Historic Effects of Humans on Biodiversity

Prehistoric farming, niche expansion, and habitat transformation (Painter of the burial chamber of Sennedjem, Wikimedia).

The co-evolution of Homo sapiens and other species began approximately 200,000 years ago, but it wasn’t until the advent of agriculture early in the Holocene Epoch—circa 10,000 years ago—that humans began having profound, diminishing effects across the spectrum of biodiversity. The negative effects started slowly, then proliferated rapidly.

In North America, for example, there were no widespread, long-lasting human populations (and possibly none at all) until roughly 13,000 years ago. Then, toward the end of the Pleistocene Epoch, Asian hunters were able to emigrate across a frozen Beringia to North America. These hunters had honed their abilities, over evolutionary time, on the Siberian steppes, and they found the wildlife of pristine North America easy prey. Mammoths, mastodons, giant bison, and ancient horses were among the many species to go extinct in a wave of hunting known as Pleistocene overkill, although the hypothesis is by no means a consensus.

What is far more certain, based on theory and evidence, is the widespread, erosive impact of humans commencing with the origins of agriculture, which in North America ranged from the early to the middle Holocene epoch roughly 10,000–5,000 years ago. Hunting remained a direct threat to non-human species for millennia, but agriculture was a different kind of threat; a more insidious threat, if less bloodily direct. Agricultural plots simply displaced native plant and animal species and their habitats.

Agricultural surplus would have had synergistic effects with hunting, too. Grain storage allowed humans to occupy areas when game was scarce; game, when available, provided a rich source of calories and protein, allowing for more intensive farming activity. In fact, as if to punctuate my point on the fundamental conflict between economic growth and biodiversity conservation, agricultural surplus was the primary prerequisite for the very origins of money.

Fast forwarding to the modern period, the human impact on biodiversity accelerated rapidly with the Industrial Revolution of the late 18th century in western Europe, early 19th century in North America, and unto contemporary history in many regions. The impact continues to accelerate as a function of population growth and economic activity; that is, population × per capita consumption, aka GDP. Biodiversity decline is now a planetary trend on the verge of becoming the sixth mass extinction.

Carrying Capacity, Habitat, and Niche Breadth

The post-agricultural and especially post-industrial decline of non-human species follows from basic principles of ecology. The most relevant concepts to start with are carrying capacity, habitat, and niche breadth.

Pikas and rock shrimp: vastly different carrying capacities on Earth (KimonBerlin, Flickr; DirkBlankenhaus, Wikimedia).

Every species is subject to the capacity of the planet. Each species has its own unique carrying capacity, too. Take pikas and bristlemouths, for example. Pikas are the quintessential alpine obligate—found only among the high peaks—while bristlemouths are the most common fish in the sea, numbering in the trillions. Carrying capacity depends, then, upon environmental conditions (starting most crudely with marine vs. terrestrial) as well as characteristics of the species in question, such as migratory ability and social behavior.

To be more specific about environmental conditions, each species has unique “habitat” requirements. Habitat refers to food, water, cover and space. Pronghorn antelope need a lot of forbs, very little free water, virtually no hiding cover (except for fawns), and vast spaces in which to see and outrun coyotes and mountain lions. It’s a unique constellation of resources that quite “fits” the size and shape and behavior of pronghorn.

Each species has a niche, too, which can be likened to the species’ “job” on Earth. How does a hummingbird make a living? By extracting nectar from flowers. That’s a pretty specific niche, which over the evolutionary ages has “produced” a unique bird in terms of shape, physiology, and behavior. Coyotes, on the other hand, have a broad niche. They can live just about anywhere above sea level and eat almost anything, although they tend to do best with meat.

All else equal, the broader the niche, the higher the carrying capacity. Red-cockaded woodpeckers eat a wide variety of insects, but they have a specialty of nesting in cavities. They and a long list of other cavity-nesting species have been hit hard by land-clearing and logging, which tends to remove the older trees conducive to cavities. Carrying capacity for cavity-nesting species, then, has been greatly reduced.

A racoon, on the other hand—while it loves cavities too—can get by holing up in just about any crack, nook, or cranny. That and a classic omnivorous diet make for one of the broader niches in nature, so the carrying capacity for racoons is generous.

Competitive Exclusion

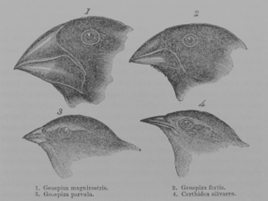

Four of Darwin’s finches: adaptation to competition on display (Wellcome collection, lookandlearn.com).

No species lives in a vacuum; each one competes with others. When niches overlap substantially, competition can become intense. Thus the differences we see among closely related species, such as the Galapagos finches so famously described by Darwin. They evolved—most notably their beaks—to specialize in specific food resources, and/or to avoid competition for other resources.

With too much niche overlap, competition will come at the expense of at least one species. In fact, the principle of competitive exclusion, aka “Gause’s law” (not to be mistaken with “Gauss’s law” of physics), is that two species with identical niches cannot coexist at length. The tiniest competitive advantage will eventually drive the “lesser” species extinct; a bigger advantage will do the job faster.

While the niche of a coyote or racoon is broad indeed, it pales in breadth compared to that of Homo sapiens. Humans can live almost anywhere on the planet and eat anything edible. You might say we have the consummate niche, terrestrially at least, and with no minor presence in the marine realm either. Plus, given our technological prowess, we can outcompete the vast majority of non-human species for virtually any resource we seek. And seek we must, if we insist upon economic growth.

Causes of Endangerment — They’re the Economy

Chicago: Huge city, intense economic activity, competitive exclusion of non-human species in the aggregate (Eray Altay, Pexels.com).

As if the principles of ecology weren’t enough to establish the fundamental conflict between economic growth and biodiversity conservation, the empirical evidence eliminates any doubt. When we look at the reasons for species endangerment in the USA and worldwide as well, we end up with a list of activities and artifacts including agriculture, logging, mining, commercial fishing, manufacturing, urban sprawl, road construction and maintenance, reservoirs and other running water diversions, powerlines and other features of the energy grid, and pollution. Each of these destroy or degrade wildlife habitats.

While Homo sapiens is making a living—farming, mining, building houses, constructing offices, providing medical care—it is essentially expressing a vast niche and operating at the competitive exclusion of nonhuman species. The effects on wildlife habitats can be overwhelmingly and abruptly destructive, as with paving. Other effect may be subtle and slow, as with a gradual increase of nitrogen levels in a lake (a common scenario with fertilizers in agricultural areas).

The salient point is that the list of activities and artifacts imperiling biodiversity is essentially a list of economic sectors and infrastructure. We have the agricultural and extractive sectors at the base (farming, mining, etc.), heavy manufacturing sectors (steel smelting, for example) that depend upon the extracted resources, and lighter manufacturing sectors that incorporate and refine the raw manufactured materials. A long list of service sectors assist with agricultural, extractive, and manufacturing activities. Infrastructure (roads, powerlines, canals) is used primarily for the transport of goods and services, as well as individual consumers and producers. Pollution stems from all these activities, with some more notorious than others (chemical manufacturing, for example).

Essentially, then, the causes of species endangerment comprise “the economy.” As the economy grows, it causes more endangerment, extirpation of populations, and ultimately extinction of species.

What about climate change and invasive species, the two other major causes of species endangerment? They only add to the case against economic growth. GDP is the key variable in determining the level of greenhouse gas emissions. Meanwhile, invasive species have proliferated as a function of international trade and interstate commerce.

COP16 Policy Implications

Putting all these ecological principles together with the empirical evidence, we can summarize that, due to the tremendous breadth of the human niche, which only broadens further via technological progress, “economic growth proceeds at the competitive exclusion of nonhuman species in the aggregate.” In other words, we humans are driving a growing list of species extinct and we’ll continue to do so unless we intentionally limit ourselves, or until we breach the carrying capacity of Earth to support us.

Most of us involved in conservation biology, ecological economics, and sustainability science are convinced that we—8 billion of us with a GDP well over $100 trillion—have already done just that: breached our carrying capacity. Such a breach can only be short-term, by definition. We are living on borrowed time, able to do so by liquidating stocks of natural capital including fossil fuels, forests, and fisheries. We either figure out how to move toward a steady state economy at a sustainable size soon, or we will be thrust into environmental and economic chaos.

In dire need of a good COP (Mainstreaming Biodiversity, Wikimedia).

This time around, then, our biodiversity COP needs to finally get it right. Not just the “civil society” elements in the Green Zone, either. We need the diplomats, technocrats, and journalists at COP16 to get it right. We desperately need high-level leadership that tells it like it is about the fundamental conflict between economic growth and biodiversity conservation, stops trying to marry the polar opposites of growth and conservation, and calls upon the parties—starting with the wealthiest ones—to get off the growth path and move toward a steady state economy.

Several highly cherished goals are so reliant on “steady statesmanship” in international diplomacy that they can practically be equated with a steady state economy. The two that come most readily to mind are biodiversity conservation and peace among nations. As we like to say at CASSE, biodiversity conservation is a steady state economy. Likewise, peace is a steady state economy. It is telling indeed, then, that the underlying theme of COP16 is “Peace with Nature.”

Brian Czech is Executive Director of CASSE.

yes! we must go from calling for economic growth to a steady state economy. However, business and its allies will be all over COP16, including their major Bloom meeting in Cali, see: https://trellis.net/events/bloom/ and they of course are calling for economic growth in order to be able to return profits to their shareholders, their sole duty. But their PR is good – for example they may give the appearance of calling for regulation but in fact are likely to be lobbying for the opposite. This is why the Global Biodiversity Framework is actually very weak on such issues.

The challenge to all of us is to find ways to translate the ideas that Brian and others share into action at the local level. Can we make these points useful and sdalient to the public officials in our neighborhoods. I testify at hearings regularly making the poit that we need prosperity rather than growth. It is slow going, but I am making some progress, especially as the climate catstrophe keeps rolling along. But the folks int heeconomic devbelopment b usiness are really trying hard NOT to learn it.

Agreed, the economic dev business people really don’t want to think this all through. I’ve started reading a book “The Collapse of Complex Societies” by Joseph Tainter, which talks about how since ancient times it’s been incredibly hard for vested interests, once established, to give up a little bit of temporary advantage to ensure the long term survival of the society that those interests depend upon. I need to finish the book and digest it before I can dare to make any sweeping statements .. but it seems that for the human brain at this stage in our evolution, altering what is rewarding *now*, in order to benefit in the future, is apparently really really hard..

RE: “before I can dare to make any sweeping statements .. but it seems that for the human brain at this stage in our evolution, altering what is rewarding *now*, in order to benefit in the future, is apparently really really hard..”

“Sweeping statements” CAN be made by taking an honest look at human activity over time and looking at the state of the planet.

The fact that nearly all socalled civilized humans CHOOSE not to change significantly their ways FOR PERSONAL MYOPIC PLEASURES AND INTERESTS IN THE NOW shows that humans are not “sapiens” (wise or rational) but clearly insane — read The 2 Married Pink Elephants In The Historical Room –The Holocaustal Covid-19 Coronavirus Madness: A Sociological Perspective & Historical Assessment Of The Covid “Phenomenon” at https://www.rolf-hefti.com/covid-19-coronavirus.html

But…

“The masses have never thirsted after truth. They turn aside from evidence that is not to their taste, preferring to deify error, if error seduces them. Whoever can supply them with illusions is easily their master; whoever attempts to destroy their illusions is always their victim.” — Gustave Le Bon, in 1895

Hello Chris,

This is one way of interpreting the potentialities of human behavior. I do want to note (as a former student of Sociology and PhD graduate in Communication) that Gustave Le Bon’s theories of crowd behavior have not been great at withstanding the test of time. I find the most convincing theses on human nature to be the ones that point out how our natures are not inherently good or bad, but shaped by context. We also, as a species, are capable of much more sovereignty over how we allow our social arrangements and cultures to shape our priorities than the last few hundred years of Western civilization may lead us to believe. Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything provides an excellent entry point into this more optimistic but empirically driven way of thinking in case you are interested in learning more.

PART 1 of 2:

Hello Helene,

Your reply only CONFIRMS Le Bon’s statement.

First of, Le Bon’s statement wasn’t about “INTERPRETING the POTENTIALITIES of human behavior” but CAPTURING the GENERALITY of human behavior. You cleverly “move the issue onto another plane” in order for you to “debunk” it. But then you supposedly have a PhD in Communication, which clearly comes in handy here, right?

You then falsely claim that “Le Bon’s theories of crowd behavior have not been great at withstanding the test of time” when the historical record of advanced humans demonstrate and validate exactly Le Bon’s statement as a general and consistent pattern. Your “convenient” self-reference to your status of “authority” (“a former student of Sociology and PhD graduate in Communication”) does not change reality. Nice try though.

In line with these falsehoods of yours you refer to a source that allegedly supports your position… “Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything”

Yet that book lacks credibility and depth.

In fact “The Dawn of Everything” is a biased disingenuous account of human history (https://www.persuasion.community/p/a-flawed-history-of-humanity & https://offshootjournal.org/untenable-history/) that spreads fake hope (the authors of “The Dawn” claim human history has not “progressed” in stages, or linearly, and must not end in inequality and hierarchy as with our current system… so there’s hope for us now that it could get different/better again). As a result of this fake hope porn it has been widely praised. It conveniently serves the profoundly sick industrialized world of fakes and criminals. The book’s dishonest fake grandiose title shows already that this work is a FOR-PROFIT, instead a FOR-TRUTH, endeavour geared at the (ignorant gullible) masses.

PART 2 of 2:

Fact is human history since the dawn of agriculture has “progressed” in a linear stage (the “stuck” problem, see below), although not before that (https://www.focaalblog.com/2021/12/22/chris-knight-wrong-about-almost-everything ). The fake hope-giving authors of “The Dawn” entirely ignore why we’ve been “stuck” in a destructive hierarchy and unequal 2-class system, and will be far into the foreseeable future. The “stuck” question — “the real question should be ‘how did we get stuck?’ How did we end up in one single mode?” or “how we came to be trapped in such tight conceptual shackles” — [cited from their book] is the major question in “The Dawn” its authors never really answer, predictably.

Worse than that, the Dawn authors actually promote, push, propagandize, and rationalize in that book the unjust immoral exploitive criminal 2-class system that’s been predominant for millennia [https://nevermoremedia.substack.com/p/was-david-graeber-offered-a-deal]!

“The evil, fake book of anthropology, “The Dawn of Everything,” … just so happened to be the most marketed anthropology book ever. Hmmmmm.” — Unknown

To cite part of Le Bon’s statement about the general behavior of the masses again … “Whoever can supply them with illusions is easily their master; whoever attempts to destroy their illusions is always their victim.”

Cole I agree, vested interests tend to hold tight particularly in a corporate setting where careers and personal financial security are at risk if individuals within business argue too much for enviroment over profit. Peer pressure affecting demand from the bottom up has examples of delivering change. Fashion houses and some celebs have turned their backs on fur where animal rights activists have successfully changed the minds of the customer base. Fur is a good example as wearing it is a visible signal, best not to be seen in it or it may be repulsive to or alienate you from others. Still desired though within in demographics where there is no strong animal rights activism, china russia and some US markets fur sales still healthy.

Success I expect will centre on somehow making it socially unacceptable to be an eviroment vandal. Socially sustainable branded goods can identify cooperating consumers eg Patagonia. Then demand will shift and the vested interests will be left high and dry.

Attached is a diagram that I think says it all, instead of words.

Cheers Tom

We certainly need a sustainable human society, if we want that the remaining “nature” continues, or even recovers to former states. In late 1980s we analyzed the global situation and human history, to conclude that humans will not be able to voluntarily achieve this, our character is too natural: first me, then others. Accepting that things will continue rapidly into the wrong direction, we decided in the 1980s to look for a place to install ourselves, which gives us the highest chance to survive the human apocalypse. We choose an area on Earth, and installed us there. Lots of vegetation and water, wild animals and few people. As always, as long as it works, it is great. When it stops, and the elevator no longer gets me to the 15th floor, nor can they pump water up there, stores are missing food, gas stations are empty…… In our case the focus was on being independent, so own energy, powder and heads to reload a few thousand, etc. Were our predictions correct? So far yes: growth in human population continued, even Switzerland doubled in few decades, and not due to own babies. There was a huge loss of more Natural habitat, increases in environmental problems (climate, water, extinctions, etc), people moving to “easier” places (countries accepting and supporting refugees), or getting into wars. Just look at our current behavior regarding tourism and traveling: many governments still completely support this, many businesses give discounts and any attraction to accelerate it, and how MANY people justify their trips for simply having fun? and all this to cause a huge environmental impact. Thus, it will only be another collapse of human society which will change directions. Unfortunately, at current dimensions, there won’t be much natural Nature left over. Most people just trust that the governments will find a solution, otherwise they will go and burn tires on the road…. but no government can solve the unsolvable, like ignoring ‘Energy Return on Investment’ EROI.

Great article Brian,

Three items/points:

1. Would you consider writing an additional article on the COP16 framework target #3 : the “30 by 30” goal of conserving 30% of lands and waters, for biodiversity purposes, by 2030? Specifically, it would be helpful to debunk the idea that 30 by 30 is enough. Haven’t ecologists pointed out that roughly 50% of nature’s ecosystems need to remain intact if they are to provide the goods and services on which humanity depends. The Qualicum Institute https://qualicuminstitute.ca/ pointed this out in our article Minister McKenna: Where is the Science?

2. Do you have a graphic that combines nature’s trophic pyramid with the human economic trophic pyramid? I’ve seen separate representations of these on the CASSE site but it would be helpful to have a combined graphic for a project I’m interested in.

3. Love the clarity in the phrase “Essentially, then, the causes of species endangerment comprise ‘the economy’ “. I just picked up a book of Canadian Endangered Frogs stamps and read on the back of the stamp booklet from Canada Post that “Loss of habitat from human activity, invasive organisms and pollutants has put these two species on Canada’s endangered list.” That is, economic growth is the cause of their endangerment. As such, the call on the cover for “our immediate intervention to save them from disappearing from Canada forever” should be to put on our big person pants and deal with economic growth.

Cheers, Terri

Really love the way you outline stuff. Thanks.