Energy and Wildlife Conservation: A Two-Pronged Approach

by Alix Underwood

At the 2024 conference of The Wildlife Society (TWS) in Baltimore, I was struck by the prevalence of one topic: low-carbon energy development. There were eight sessions with “renewable energy,” “solar,” or “wind” in their titles, and issues related to these energy sources permeated many other sessions. At a policy priorities meeting, low-carbon energy dominated the discussion, with professionals and academics from across the country sharing their unique concerns. According to Joseph Roy, a wildlife biologist from Maine with experience in the public and private sectors,

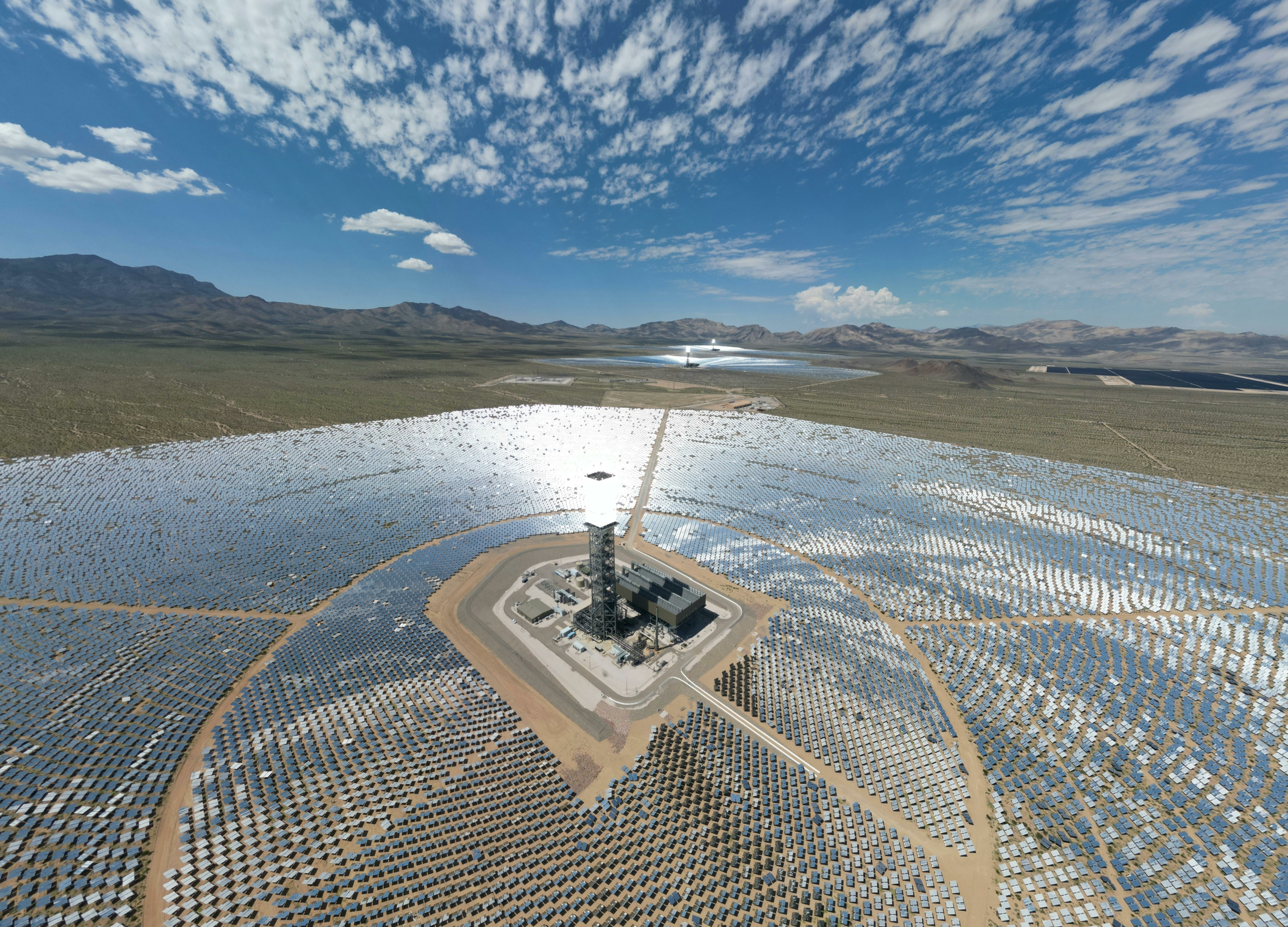

The Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System’s three plants collectively occupy 3,238 acres in the Mojave Desert (James Guetschow, Pexels).

“We need to strike a balance between wildlife needs and renewable energy needs. Oftentimes the areas targeted for energy development are open landscapes and grassland communities. Since we have so few of these communities in Maine, our species that rely on them are very limited and often of greatest conservation need. Proper siting is critical to mitigate impacts on habitats while addressing important renewable energy needs.”

Proper siting. This was the resounding call of the wildlife professionals at the conference: Don’t put solar and wind farms on land that threatened species and ecosystems depend on. The popular sentiment was that education and collaboration could mitigate bad siting. Corporations and local policymakers should be educated on best siting and permitting practices, and both parties should consult wildlife professionals earlier and more often.

However, despite the faith in proper siting, there was an undercurrent of apprehension about the scale of development and the lack of data to quantify its impacts. In one session, a researcher asked a panelist from Deriva Energy why the company’s data wasn’t available to academics, frustration creeping into her voice. The panelist responded frankly that journalists and advocacy groups would weaponize it. The data didn’t paint a pretty picture, notwithstanding climate-change mitigation efforts.

How does fossil-fueled climate change impact wildlife, and how do these impacts compare to those of low-carbon energy? Rigorous comparisons are lacking. Establishing a “counterfactual”—a scenario in which the low-carbon energy facility had never been developed—is a complex undertaking. The consensus is that fossil fuels are worse, but low-carbon energy impacts are far from negligible. Halting the sixth mass extinction will require a two-pronged approach: transitioning to low-carbon energy and reducing energy consumption.

Wildlife Struggles to Adapt to a Changing Climate

The ten warmest years in the historical record were 2014–2023, and 2023 almost breached the agreed-upon boundary of 1.5 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial baseline. For the same reasons this doesn’t bode well for humans, it doesn’t bode well for wildlife. Rising temperatures impact the food supply and reproduction of many species, and invasive species often fare better than native ones. For example, the invasive brown trout, which does better in warmer water, is outcompeting the native brook trout in the eastern United States.

Weather-related natural disasters, which increased five-fold from 1970–2019, also impact wildlife. Floods can lead to severe water pollution, eroded soil, and drowned tree roots, degrading ecosystems that wildlife depends on. Wildfires can also be devastating: Australia’s 2019–20 Black Summer bushfires are estimated to have killed or displaced three billion animals.

Bushfire on Australia’s Kangaroo Island (New Matilda, Wikimedia Commons).

Experts estimate that climate change has already increased the extinction likelihood of almost 11,000 species on the Red List of Threatened Species. In a study looking forward to 2100, researchers estimated that the number of species exposed to dangerously high temperatures will double, from fifteen to thirty percent. They warn that we are approaching a critical tipping point.

The climate has undergone massive changes before, but this time around is unique. Researchers estimate that recent global warming is happening an order of magnitude faster than the warming that straddled the Paleocene and Eocene epochs. During that period, 56 million years ago, biodiversity increased. This is likely because organisms were able to migrate large distances, unimpeded. Today’s wildlife doesn’t enjoy this luxury. In addition to habitat loss and fragmentation, species must contend with a long list of anthropogenic pressures, including pollution and overexploitation. Let’s add low-carbon energy development to the list.

Low-Carbon Energy and Wildlife Conservation

Low-carbon energy technologies are just one set of tools for combatting climate change. Yet, because they align with the dominant green growth narrative, wildlife organizations prioritize them above other mitigation methods. These technologies can drastically decrease greenhouse gas emissions per kilowatt-hour, but their buildout and maintenance require minerals, land, water, and, as it stands, fossil fuels. In other words, they are embedded in the trophic structure of the economy and cannot be absolutely decoupled from environmental impact. Indeed, biologists have been documenting the effects of low-carbon energy development on wildlife for decades.

Hydropower

Hydropower supplied seventeen percent of global electricity generation in 2020. As of 2017, there were over 58 thousand dams large enough to impound more than three million cubic meters of water. Arguably the low-carbon energy most infamous for its wildlife impacts, hydropower severely alters aquatic ecosystems and watersheds. Reservoir creation floods large areas of land, destroying terrestrial habitats. Species that rely on tropical lowland habitats, such as jaguars and tigers, have been especially impacted.

Dams disrupt river connectivity, blocking the migration routes and reproduction patterns of anadromous species like salmon and freshwater species like sturgeon. They also alter water conditions, such as temperature, oxygen, and sediment levels.

Another cause for concern is that dam construction and operation go hand-in-hand with the development of roads and other infrastructure in previously remote areas. This drives an overall increase in human activity, including deforestation and poaching.

Wind

Wind accounted for almost eight percent of global electricity generation in 2023. By my rough calculations—using global wind energy capacity, average turbine capacity, and estimates of the share of onshore versus off-shore turbines—the world has about 300,000 wind turbines.

The hoary bat is the unfortunate species most frequently killed by wind turbines in North America (J. N. Stuart, Flickr).

Turbine collisions directly affect birds and bats. Bats are also susceptible to internal injuries and death by “barotrauma,” which is caused by sudden pressure changes from turbine blades. Researchers estimated 2012 bird fatalities at around 600,000 and bat fatalities at around 900,000 in the United States. Annual bird fatalities are now likely in the one-million range.

Wind farms also affect wildlife less directly by reducing or fragmenting habitats. Though the land below and around turbines appears largely untouched, many species avoid these areas due to noise, movement, and human activity. Offshore wind farms also impact wildlife, for example by disrupting the communication and migration patterns of marine mammals, such as whales and dolphins.

It is worth mentioning that wind development (any energy development) can also negatively affect human communities. In Lincoln County, Oklahoma, for example, the impacts of rampant wind development are turning citizens against Big Wind.

Solar

Solar photovoltaic is the third most prevalent low-carbon energy source. In 2023, solar accounted for 5.4 percent of global electricity. Though small-scale, strategically sited solar infrastructure is less harmful to wildlife than hydropower and wind facilities, most development to date has been utility-scale. Large solar farms degrade and fragment natural habitats. Wildlife, especially birds and bats, may mistake reflective panels for water bodies, which sometimes results in collisions and fatalities.

Solar farms can also attract certain insects and repel others, altering ecosystem dynamics. A study of Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System in the Mojave Desert revealed that the quantity and diversity of pollinators at the solar farm were significantly lower than at control sites.

The Mojave Desert is home to a slew of utility-scale facilities, the installation of which often entails complete vegetation removal. The desert is also home to a wealth of species—not just pollinators—many of which are imperiled. Solar development has particularly affected the threatened desert tortoise.

An Uphill Energy Battle

Researchers have observed the impacts identified here at the levels of low-carbon energy development to date. Yet we have a long way to go, and we need to get there fast for effective climate protection. The U.S. National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) estimates that a full transition to zero-carbon electricity would require increasing wind and solar to between 60 and 75 percent of the U.S. electricity mix (they stood at fourteen percent in 2022). To reach that goal by 2035, we’d need to more than quadruple annual deployment rates for both technologies. This would have to be accompanied by the construction of thousands of miles of high-capacity transmission lines per year.

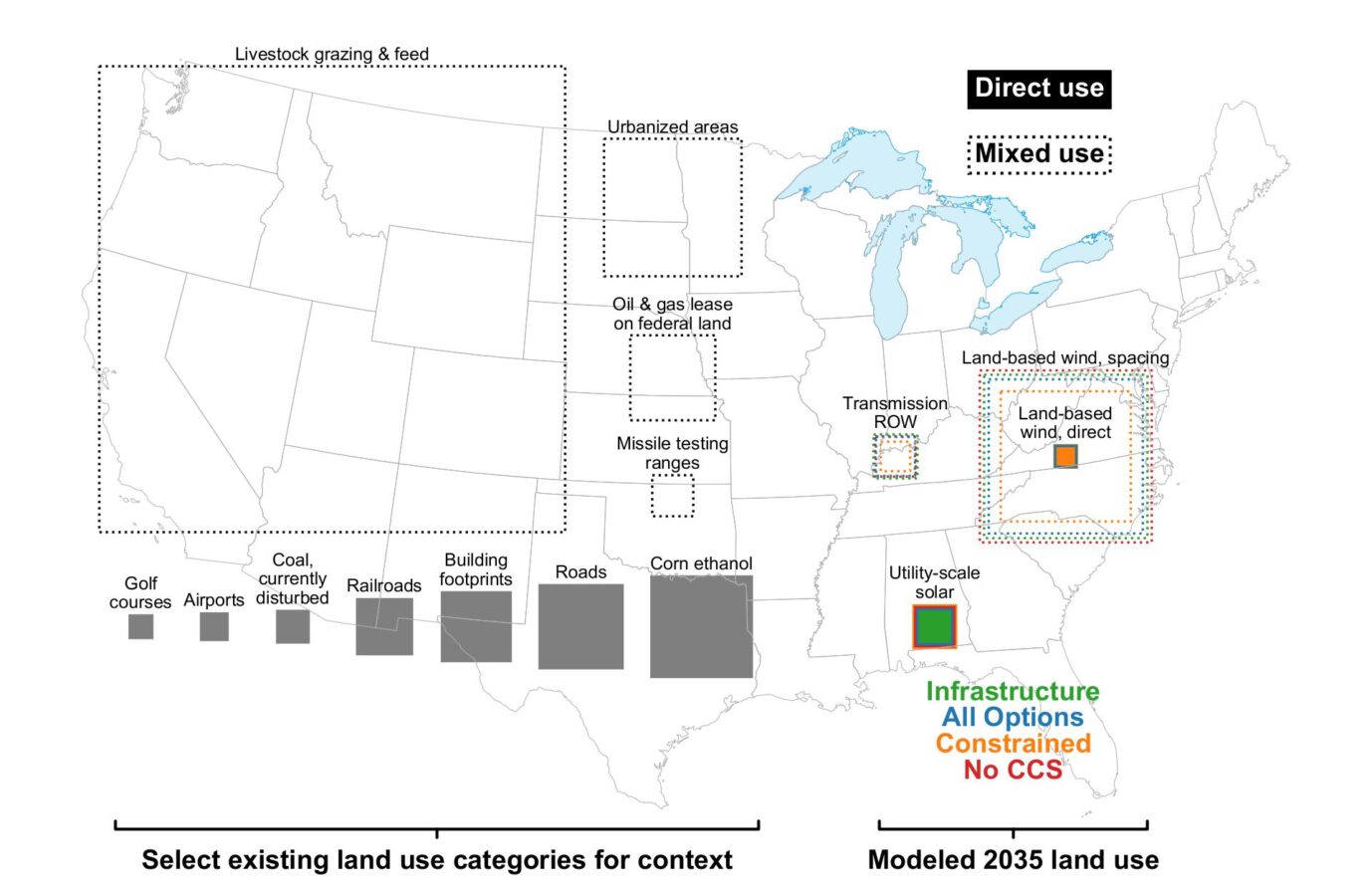

Estimated wind and solar land use in NREL’s 2035 zero-carbon-electricity scenario, shown alongside land use for other economic activities (NREL, Examining Supply-Side Options to Achieve 100% Clean Electricity by 2035).

These numbers are daunting, but NREL paints a rosy land-use change picture. They estimate the necessary buildout would require less than half the land occupied by active oil and gas leases. However, these estimates only account for land directly occupied by infrastructure, which makes up two percent of the land within a wind farm, for example. That may be good news for other human activities (for example, agriculture), but not necessarily for wildlife. Ideally, we would install new low-carbon energy facilities in lands already scarred extensively by economic activity. However, as wildlife professionals at the TWS conference expressed, that often does not happen.

Competing and interconnected demands—agriculture, housing, infrastructure, etc.—make win-win siting difficult, especially as energy demand continues to grow. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimates that global primary energy, meaning all forms of energy consumption (not just electricity), will increase by between 16% and 57% from 2022 to 2050. Population growth, more economic activity, and higher living standards drive this increase. In all but their “Low Economic Growth” scenario, EIA projects that growth in energy consumption will result in more CO2 emissions than efficiency advances save.

A Second Prong for the Conservation Approach

If we truly want to protect wildlife—and ourselves—from climate change, we need to transition to low-carbon energy sources and consume less energy. The best way to achieve this is degrowth toward a sustainable, steady state economy. However, many conservation groups are married to the green growth paradigm and find it difficult to imagine a lower-consumption future.

No matter how you slice it, harnessing energy for human consumption has heavy environmental impacts (Jason Wong, Lookout Point).

TWS is one of the few scientific, professional societies that officially acknowledges the fundamental conflict between economic growth and wildlife conservation. Congruent with this, its position statement on Energy Development and Wildlife concedes that “all forms of energy development can affect wildlife and wildlife habitat.” Yet rather than calling for a decrease in energy consumption—in addition to a transition to low-carbon energy—TWS simply accepts that “worldwide energy demands will continue to increase.”

TWS’s energy development policy recommendations focus exclusively on proper siting, monitoring, and evaluation. They are not unique. “Big Green” environmental organizations like Defenders of Wildlife advocate for policies to make renewable energy “wildlife friendly.” The National Wildlife Federation has developed a Clean Energy Transmission Policy Platform, with no mention of overall consumption decreases.

Consuming Less for Our Fellow Beings

Some environmental organizations, such as the National Wildlife Federation, do encourage individuals to conserve energy. Individual behavior change can indeed go a long way. A short list of examples would include: 1) avoiding status-driven or unnecessary items that require high energy inputs during production and use; 2) opting for walking, cycling, or public transport instead of driving or flying (or simply traveling less); and 3) shifting to a plant-based diet sourced locally when feasible, as animal and industrial agriculture are energy-intensive.

We also need policies to incentivize behavior change and to reform systems and institutions that perpetuate energy-intensive lifestyles. The current U.S. administration may not be amenable to such policies, but we can advocate for them at other levels of governance. They include:

- Caps on energy use for non-essential production

- Taxation and carbon-pricing mechanisms

- Provision of universal basic services, such as transportation and healthcare, to de-commodify them and reduce the need for private, energy-intensive alternatives

- Encouragement of decentralized, community-controlled energy systems that prioritize sufficiency over profit

Any organization fighting climate change should advocate for consumption-reducing behaviors and policies. However, the development of this “second prong” is particularly relevant for wildlife conservation, given the known impacts of the first prong, low-carbon energy, on nonhuman species. To secure a livable Earth for all, we must alter our economic priorities.

Alix Underwood is managing editor at CASSE.

Alix Underwood is managing editor at CASSE.

Hi CASSE:

It is great to see you pointing out the need to “lead the charge for reduced consumption.”

As your feature article says:

“. . . we need to transition to low-carbon energy sources and consume less energy.”

“Any organization fighting climate change should advocate for consumption-reducing behaviors and policies.”

Any thorough analysis will recognize that the consumer life-style is not compatible with long-term well-being.

Cutting back is one way to reduce consumption, tho it tends to be looked down on by a society conditioned by endless advertising promoting more consumption.

Alternatively (in addition) we can encourage people to reclaim the sort of activities that filled our time before industrial production became so robust that we had to be trained to consume the volumes of stuff produced.

Life-based activities ( http://www.sustainwellbeing.net/life.html ), learning, love and laughter, along with appreciation, sport, music and the like can make our lives so fulfilled that we wouldn’t have time nor much interest in excess material consumption. An experiential carrot to accompany the cutting back stick.

In a nutshell: “More Fun, Less Stuff” ( http://www.sustainwellbeing.net/Key.html ).

For a sustainable world,

A very important point you make; for those of us (myself included) with energy-intensive lifestyles, reduced consumption can accompany more fulfilling lives! I often forget to bring out the carrots, so thank you for doing so. And thanks for the links!

Thanks for the article, in particular the tortoise mention! I also liked reading about the brown trout, jaguars, and tigers. Thanks for shedding light on the more nuanced issues within green energy.

Energy production such a big problem with no singular answer. In trying to break it down, I thought about my own state. What percent of power created in Wyoming (oil, gas, wind) stays in Wyoming? Energy extraction is a major industry here. I think I want a more direct source of electricity. Like I want everyone to get it from their own backyards.

Reclamation is a current standard within oil/gas production. And I didn’t see any mention of it in your article. Not sure the rules when it comes to solar and wind regarding reclamation. I think solar in Nevada is often a fixed term lease, implying there would be some mitigation at the end of that time.

I worry about the math about energy extraction. You hear about the production of windmill blades and see semis hauling them all the time in the summer. It takes a LOT of fuel to move those things. But once you add that, where do you stop?! Do you included the McDonalds sandwich the driver ate that day?!

You’ve read a bunch. Does solar on homes, parking lots, and businesses seem to be a viable solution? It would give locals self sufficiency, while not disturbing additional habitat. However I imagine it’d be more likely to be destroyed by troublemakers. Is my desire for power from your own backyard a very western mindset?

I agree, the actual answer is LESS consumption. This was all on my mind before I read your article. Today I drove 70 miles round trip to go xc ski. I also have no drive days in an effort to ameliorate my gas use. This doesn’t make me a good person, but rather someone who is cognizant of their behavior and curious about finding the middle ground. I’m thankful for my friends and colleagues who work and live to protect public lands. Thanks, Alix!

Best,

Jo

Thanks for these thought-provoking comments, Jo! Yes, I think solar on homes, parking lots, and businesses is much better than raking the Mojave Desert for massive solar farms (though still not without environmental impact; I didn’t really touch on mineral extraction and manufacturing in this article).

I think what’s keeping that from happening more is the commodification of energy by big corporations. I would’ve liked more room in the article to talk about this big business, commodification issue. If we do low-carbon energy like we do everything else–industrial, utility scale, profit driven–of course companies will choose massive desert farms over roof panels! They’re all about efficiency, which is often associated with sustainability, but we at CASSE promote the more appropriate goals of sufficiency and optimization.

Great article summarizing the problem. As far as using less energy, a sustainable human population is vital. Somehow, people have to start making the connection between climate change and species extinction, and their choice of how many children to have. There is no conservation measure that has more effect than choosing less children.

Thank you Alix for an informative article and good research in attending these events.

Like Jo, it frustrates me to see vast commercial rooftop space in our metropolises void of solar panels. I’ve asked this question in public forums to the relevant energy authorities without a satisfactory answer. It would minimize transmission lines and loss and the expense of acquiring land far afield that often displaces farms or natural habitats.

I think we need to be very careful when promoting less consumption (which is crucial) to emphasize that wealth redistribution is necessary to achieve it to protect people’s living standards. Consuming less energy in particular does not necessarily mean discomfort.

Thanks Alix for your thoughtful article. My wife and I have been living for the past 25 years in a way we hoped would lower our impact on the environment. What follows is a brief summary of how we live and what that means in terms of our ecological footprint.

LAND BASE: 160 acres; mix of native prairie and former cultivated land put back to “native” permanent cover in 1990 and mostly “managed” for wildlife by taking a hands-off approach.

HOUSING: Self-built, passive solar, straw-bale house built in 1996.

POWER: 18.7 kw grid-tied solar panel array; wood-burning stove.

FOOD: Approximately 50% of plant material grown ourselves; chicken/eggs grown and processed with friends and red meat primarily wild venison (road-kill).

WATER: 5,000 gallon cistern- total consumption about 20 gallons/day; Composting toilet; Rubble trench grey-water disposal.

APPLIANCES/LIGHTING: Low-energy; NO clothes dryer, microwave, TV, air conditioner, etc.

TRANSPORTATION: EV (2013 Chevrolet Volt). We no longer fly.

CLOTHING: Primarily second-hand.

Our total footprint is still 3.4 global hectares (gha) and our ‘overshoot day’ is July 1. We

have only managed to cut our footprint by a little more than half the North American average

of over 8 gha/person compared to a world average of 2.75. Unfortunately, most people of the

developed world would probably find our lifestyle unacceptable although much of the rest of

humanity might be pleased to be brought up to our level of consumption.

If you accept these assumptions and numbers as being reasonably accurate, it suggests the current human population (all living at North American standards) is almost five times larger than biocapacity (1.63 gha/person). If we left half of the planet for the millions of other life forms not directly part of our food chain, it suggests a sustainable human population below a billion. It should be remembered that the biocapacity of the earth is currently being constantly degraded as the population continues to grow.

In terms of solutions, we appear to be in a real predicament. It does not appear that the developed world is ready for voluntary degrowth. Virtually every politician’s focus is still on ‘growing the economy’. Society may continue fighting the reduction and stabilization of the human enterprise to the bitter end hoping science and technology will continue ‘removing’ limits to growth. This would leave Mother Nature to achieve the balance and her tools are disease, starvation and war. Hardly a viable recipe for sustainability.

Your article is amazing! (I am sending it as homework for my students). As I grew up, the great benefits of “clean” energy sources were always brought up as perfect solutions opposed to the terrible evil that were carbon ones. In Brazil, over 60% of our energy supply comes from hydropower, always been “sold” to us as a reason for great pride, meanwhile ignoring the countless animals that died implementing this technology, including one of the deer species I work with: the Marsh deer, a species highly dependent on wetland habitats that cease to exist where dams are installed. This scenario is something that needs to be talked about and discussed, as there is no perfect way to deal with the energy production crisis. One thing that you mentioned that makes this very complicated was in this extract: “Population growth, more economic activity, and higher living standards drive this increase.” Right now, countless people do not have access to electricity as seen in most rich developed countries. One story a teacher of mine told really stuck with me was: he was attending a construction site for a dam in the north of Brazil, in order to relocate them to diminish the impact this project would have on local fauna. He went to a bar and explained to the locals what he was doing and the terrible effects the dam would cause for wildlife. One local replied that he couldn’t care less. He was just glad he would finally have energy available for 24h, being able to finish watching movies at night, using fans to endure the terrible heat and be able to care properly for his kids when they were sick. Things we take for granted. How do we deny others higher living standards we were blessed with? Is there a way to reduce energy consumption enough but still allow everyone access to good living standards? Should the focus of energy reduction campaigns be aimed at the people or at rich, powerful individuals, industries (such as agriculture) and companies that have higher consumption rates?

Thanks for reading my article, Luana. :) That’s so encouraging! Yes, as someone who works in conservation biology, you understand this conflict more than most. And I totally agree that the campaigns should be aimed at the rich and powerful! The justice component–it’s the rich who need to change–is what drew me to ecological economics. I miss our deep conversations about these things!

Hello Alix & CASSE

I’m a bit late here but catching up with emails I’ve saved for later!

The predicament is the same here in Australia. Most green groups either seem to assume that technology will solve the problem sometime or other, or ignore the consumption aspect of environmental damage. Many environmentalists possibly ignore it deliberately, as they understand the reluctance of the average person to accept that their standard of living is way higher than necessary, especially when our politicians keep telling them that our standard of living has dropped, as if it’s a bad thing! The message seems to be that we can keep our consumption if the goods are produced with ‘green’ energy. Of course the corporate run media is happy to promote this! There is now a big backlash in Australia to green energy projects, especially as many of them are being slated for greenfield sites requiring clearing of huge acreages. It is pitting environmental groups against each other, for example the Rainforest Alliance against a central Queensland development which required 3000+ acres to be cleared. The easiest, most cost effective way to reduce emissions is USE LESS ENERGY!!!! Drive less, buy less.