Circularity in the Gold Sector

by Ramachandran Kallankara and Vivek Vivek

Twenty years ago, visionary economist Herman Daly exhorted the readers of Scientific American to create new ways of thinking towards a sustainable economy:

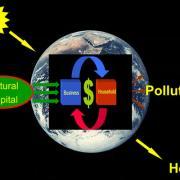

“The global economy is now so large that society can no longer safely pretend it operates within a limitless ecosystem. Developing an economy that can be sustained within the finite biosphere requires new ways of thinking.”

Economies are triangular, relying on a broad base of agriculture and natural-resource extraction. Value is added as one proceeds from the trophic base to the higher trophic levels of economic production.

That said, circularity is a promising new way of thinking for certain economic sectors. Recycling (of the final products), a key component of circularity, entails converting waste into valuable materials, which is generally energy intensive. Therefore, circular economics can only solve our ecological predicament if it accompanies a halt to unfettered economic growth.

Globally, the annual generation of e-waste—laced with gold—increases by 2.6 million metric tons a year. (Ekolist, Wikimedia Commons)

Nonetheless, the concept of circularity is a fundamental part of the global shift towards a steady state economy. Circular economists promote many “R’s”, but we will focus on “Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle” in the context of the gold sector.

Gold, a highly valued metal, presents a paradox: It has limited practical applications (less than seven percent of demand), such as in electronics and healthcare, but enormous economic and cultural demand. Societies attributed value to gold as far back as 4,000 BC. This is because gold is virtually indestructible and at the same time scarce.

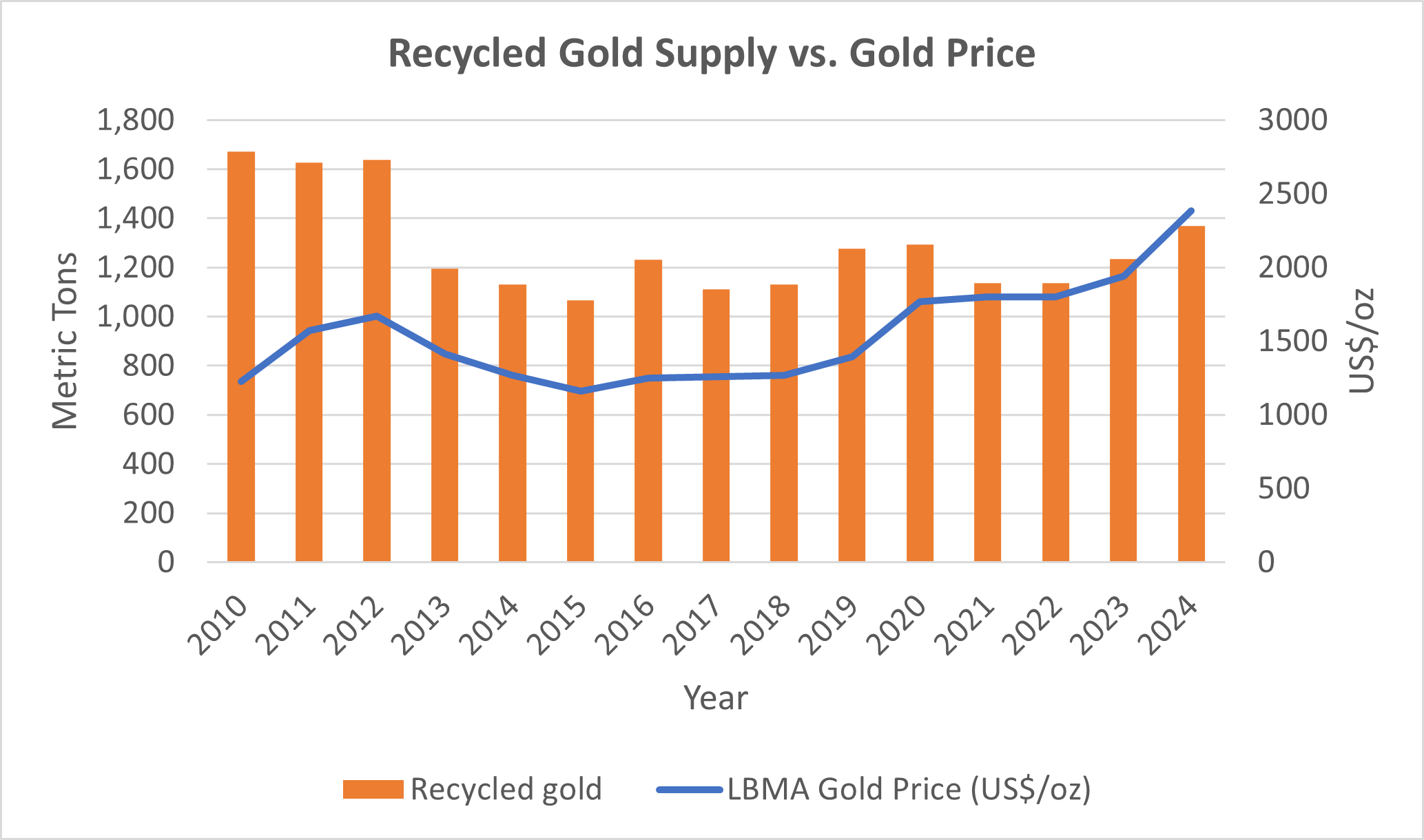

Fortunately, gold’s properties and purity can be maintained in the recycling process. In 2024, recycled gold met about 30 percent of demand, according to data from the World Gold Council. There is already a market for recycled gold, but it needs strengthening.

Why Do We Need Circularity in the Gold Sector?

Like many other mining industries, gold mining is environmentally destructive and socially exploitative. Extracting a small quantity of gold requires the removal of vast amounts of rock. The average mine generates 100 to 2,000 kilo-tons of waste rock and ore per ton of gold, and even the most efficient mines yield only 0.001 percent of gold by weight. Given these proportions, gold mining can destroy entire mountains and ecosystems.

In addition to intensive land use, gold mining involves massive water consumption (265 thousand liters for 1 kg of gold) and the use of toxic chemicals, such as cyanide and mercury. The industry is responsible for 38 percent of mercury emissions (largely from artisanal mining) and 0.3 percent of carbon emissions globally. Extracting and processing a metric ton of gold requires around 150 megawatt-hours of energy, with a footprint of 30,000 tons of CO2 (scope 1 and scope 2 emissions from mining).

The ideal solution is to reduce the demand for gold. However, the reality is we’re not heading in that direction. Any significant reduction in gold mining will require increases in recycling, which is not nearly as environmentally destructive. Compared to mining for fresh gold, recycling requires 10 to 50 percent of the energy. It uses less water. It generates 50 to 90 percent less CO2.

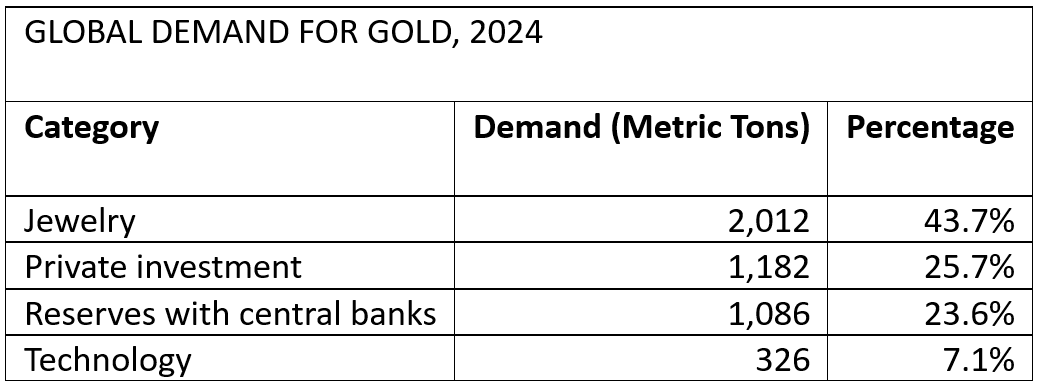

Demand for gold is unique, given its concurrent uses as a commodity and a store of value. (World Gold Council)

As for social impacts, the gold sector is linked to exploitative labor practices, land disputes, and economic inequality. Many mining regions suffer from poor working conditions, displacement of local communities, and unethical business practices. Some vested interests refute these impacts, yet even the gold-promoting community recognizes the demand for gold that is more consonant with environmental sustainability and socio-economic development. It’s time to rethink how we produce, consume, and value gold.

Pathways to Reduce Gold Demand

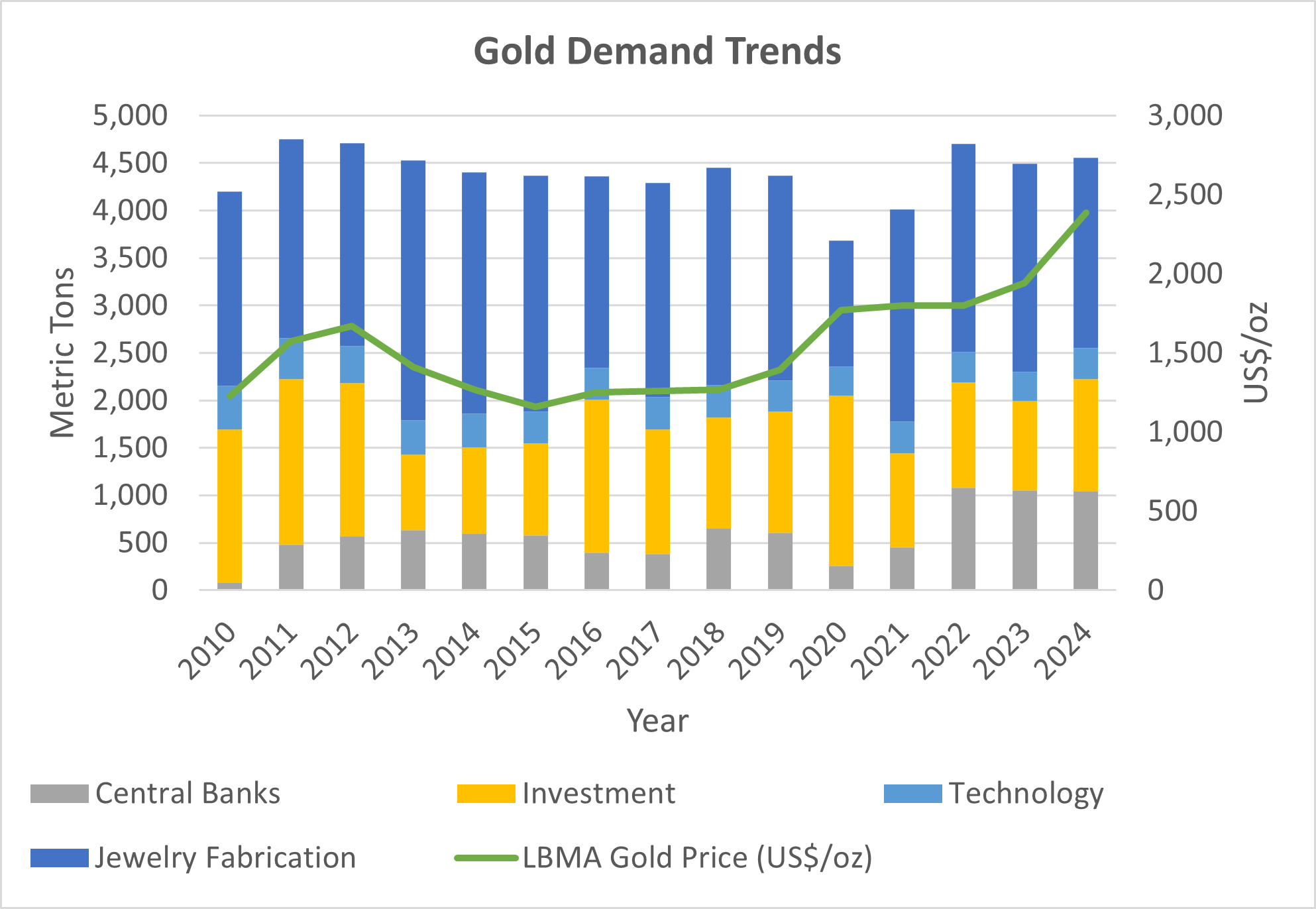

Demand for gold has increased over the past decade, and is surging in 2025. (World Gold Council, LBMA = London Bullion Market Association)

Achieving a significant reduction in gold mining will be difficult but, as they say, “well begun is half done.” A natural starting point is the reduction of individual usage of jewelry and luxury items, which constitute almost 38 percent of gold demand. Simply making people aware of the ecological and social costs of gold can drive them towards alternative materials and, ideally, less consumption.

Classes with more disposable income are most relevant to a consumption shift. Younger generations may be most willing to change, as they will face the burdens of unsustainable growth more than their elders.

Public figures hold power to accelerate change by refusing to use gold, citing its enormous social and environmental burden. Some celebrities have taken a positive stand on personal health issues, such as tobacco use. They could have a huge impact by extending their support to the health of the planet and promoting a reduction in gold use.

Another key strategy is to promote the use of digital assets as a modern replacement for gold as a financial asset. This can help alleviate demand from central banks and investors. Stablecoins, which are cryptocurrencies pegged to a fiat currency like the U.S. dollar, are slowly gaining traction with central bankers. Based on Ethereum, stablecoin uses 99 percent less energy than the infamously energy-intensive Bitcoin. Incorporating these types of environmentally lighter digital assets into central banks’ mix of reserve assets could reduce reliance on gold and impact on the environment.

As for technology fabrication, gold is sought after for its conductivity, pliability, and resistance to tarnishing, among other desirable properties. Alternatives exist that can replicate these properties, such as graphene and alloys of silver and copper. These possible substitutes, alongside reductions in overall demand for electronics, could significantly decrease gold demand in the technology industry.

It is also important to note that the mining industry, particularly artisanal mining, employs many people, especially from the Global South. Hence, we should aim to reduce gold mining judiciously, so as to minimize impacts on these people. We need to carefully consider the strategies that we adopt, as second- and third-order effects are often difficult to predict.

Increasing Reuse and Recycling in the Gold Sector

Reducing gold demand is a long-term strategy that will require patience and determination. This is because of gold’s entrenched cultural significance and the lack of alternate “secure” assets for central banks and investors. However, steering the gold industry towards circularity—via reuse and recycling—is a shorter-term strategy that we should pursue with utmost urgency. Many initiatives are already underway.

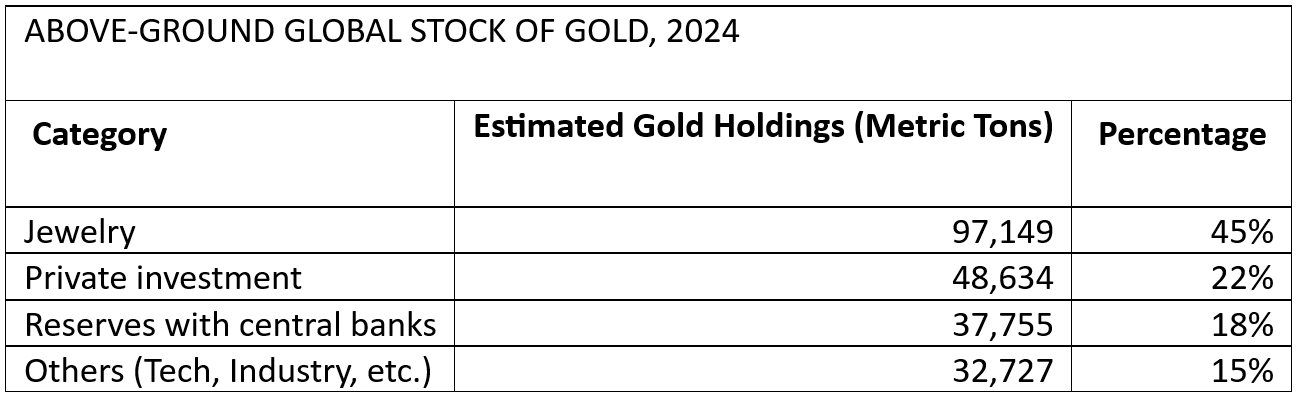

There are only about 50,000 metric tons of gold below ground that can be economically extracted. Eventually, we’ll have no choice but to recycle. (World Gold Council)

At a high level, these are some key strategies to follow:

Reintroduce already-mined gold by bringing the “gold in the locker” into the market. This frees up locked capital for other, more productive economic activities. New business models for jewelry refurbishing and buybacks can help reintroduce gold.

Enhance efforts to recycle gold from jewelry. Pandora has a program where they sell jewelry from 100 percent recycled gold. Tanishq, India’s largest jewelry retail chain, has an exchange scheme that about three million customers have used to exchange their old jewelry for new. Though a step in the right direction, this doesn’t fall under the World Gold Council’s definition of recycling.

Enhance efforts to recycle gold from waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE). Recycling gold from WEEE is more complex than recycling it from jewelry. Only about 15 to 20 percent of WEEE is recycled. Increasing WEEE recycling to 50 percent would result in about an additional 500 metric tons of gold being recycled. Some technology companies have successfully established gold-recycling programs. Apple, Dell, and Samsung have “reverse supply chains” for gold recycling. In Japan, urban mining, or recovering valuable materials from discarded electronic devices, is booming.

Advance technologies that reduce the cost of recycling. For example, automation and nanotechnology can be used for more efficient gold recovery.

Launch educational campaigns about the environmental and social impacts of gold mining. Consumer behavior change can make a huge difference. The private sector can leverage such campaigns by using (legitimate) certifications to promote jewelry and electronics made with recycled gold.

Governments have a role to play here. They can incentivize gold recycling using financial mechanisms like tax breaks and subsidies. These can be used to persuade jewelry and electronics manufacturers to incorporate a certain percentage of recycled gold into their products. Governments can also limit new mining licenses, establish a cap-and-trade system for mining tonnage, schedule downsizing of caps, enforce stricter environmental and ethical standards on existing mines, and tax products made with new gold. They can mandate “take-back” programs, in which companies provide benefits to consumers who turn their products in for recycling.

Imagining an Alternative Gold Sector

To date, recycling has been tightly linked to the price of gold. (World Gold Council)

Recycling has the potential to reduce new mining and, in turn, carbon emissions, deforestation, soil erosion, habitat loss, and water use. However, it is important to ensure that recycling itself is within ecological limits. Gold recycling is not without environmental impacts, though they can be 300 times smaller than mining. There is also a need for strategies to delink recycling from the price of gold, so that recycling increases even if gold prices decline.

Can we reimagine gold as a resource that works for people and the planet, rather than against us? We are not talking about imagining new frontiers to exploit. Apparently, asteroid 16Psyche, which NASA and SpaceX are exploring, has enough gold to make each earthling a multi-billionaire. This whimsical finding could fend off gold scarcity, but what would be the second- and third-order effects of mining asteroids for gold?

Scientists who have dedicated their lives to research of the material world contend it is very unlikely that we can rely on other planets for our continued growth. Why not appreciate the planet we have by acknowledging the preciousness and finiteness of its resources? Why not start with gold?

Ramachandran Kallankara is a Supply Chain Consultant with ValueQwest Singapore.

Ramachandran Kallankara is a Supply Chain Consultant with ValueQwest Singapore.

Vivek Vivek is an Independent Researcher investigating Human Behaviour and the Environment.

Vivek Vivek is an Independent Researcher investigating Human Behaviour and the Environment.

Thank you both Vivek and Ramachandran for this. I am not an expert but indeed, it seems gold would be an excellent starting point for establishing a genuine circular economy.

The value of even very small amounts of gold is perceived as being so high, that it is worth the effort in research and applied science to figure out how to reclaim every bit of gold that we can from the waste stream. I think too that it is highly likely that any clever processes developed to pull miniscule amounts of gold from a waste stream will turn out to be processes that can be applied to other materials. So perhaps after a while, as gold capture processes are increasingly perfected and made cheaper, people would say: Hey, with a few changes, we can actually use this to reclaim copper and nickel, too. And so on.

That’s a very powerful suggestion for other metals, Cole! While we did not mention this exact detail in the blog (there are strict word count limits), we also thought that gold can pave the way for many other metals and materials.

For example, steel is already well down the path of large-scale recycling, but it is energy intensive (like all recycling). And crude steel production is still going up. Source: https://worldsteel.org/wider-sustainability/circular-economy/