Corporate Conservation Funding: A Contradictory Conundrum

by Kali Young

Paper products are a major factor in deforestation. (Adobe Photostock)

Apple, Cargill, Walmart, United Airlines, Chevron, BlackRock, Starbucks, Ford Motor Company, Amazon, McDonald’s, Sotheby’s…What do they all have in common? They are among many megacorporations that fund Conservation International, one of the most prominent conservation foundations in the world. World Wildlife Fund and the Conservation Fund, also conservation powerhouses, have similar though less expansive funder profiles.

Walmart and BlackRock are two of the world’s top deforestation perpetrators. Along with other corporations that support conservation nonprofits, they are drivers of economic growth, which always comes with an ecological footprint. This contradicts the philanthropic aims of the foundations they create.

These conflicts of interest can cripple the formation of true and effective conservation strategies. They can silence debate and cause philanthropic leaders to ignore the need for systems change. This problem stems from two interrelated conundrums: 1) Funds are created via environmental destruction. 2) Funds have strings attached to growth-driven corporations. Limiting economic growth (the expansion of production and consumption) would mean less profit and, likely, less foundation funding. Therefore, this goal is often preemptively taken off the table.

Amazon Fuels Deforestation While Funding Conservation

The biggest driver of biodiversity loss is “land and sea use,” undertaken for the sake of economic activity. One of the most destructive types of global land use is commercial forestry, leading to deforestation, much of which is driven by consumption in wealthy countries. Packaging, which has increased by 65 percent over the past two decades, has had a huge impact on forests. One to three billion trees are pulped annually to produce hundreds of millions of tons of shipping cartons.

Online retail packaging contributes significantly to deforestation, estimated to be in the billions of trees annually. (Adobe Photostock)

When most of us think “shipping cartons,” we think Amazon. The second largest corporation in the world, Amazon boasts 37 percent of the market share of online retail commerce. With its vast operations and lengthy supply chains, Amazon is clearly a top contributor to deforestation.

In a statement for the Steady State Herald, Amazon spokesperson Margaret Callahan said the company is shifting to shipping products with only a label and no additional packaging. They said Amazon has shipped 5.5 billion products that way in the last five years (this is less than the total number of packages it ships annually). However, Callahan declined to comment on the company’s quantitative contribution to deforestation.

Amazon has a robust sustainability plan and report, along with an impressive slate of climate and conservation programs. It has committed to a climate pledge of net-zero emissions by 2040. The company has donated hundreds of millions of dollars through its collaborative Right Now Climate campaign and contributed to a one-billion-dollar joint funding pool for the LEAF Coalition, an initiative to conserve tropical rainforests. As a separate entity, the Bezos Earth Fund donated a portion of its $10 billion to plant approximately 100 million trees.

The question isn’t, “Is Amazon (and the Bezos Earth Fund) doing anything about conservation?” but rather, is it doing anything relevant, relative to its profit and environmental impact? Amazon profited $59 billion last year. With half that amount, it could fund planting about three billion trees per year at $10 per tree. However, Amazon’s conservation funding is earned via deforestation. Therefore, we should prioritize limiting the company’s initial impact over increasing the funding it provides.

The problem with the destroy-and-reforest approach is that the damage caused by cutting down a tree for shipping isn’t canceled out by simply planting a tree elsewhere. Deforestation destroys ecosystems that can take centuries to regain their complex webs of interdependent relationships. In some cases, ecosystems are altered so much that they can never recreate the habitats that species require for survival.

Corporate Commitment or Greenwashing?

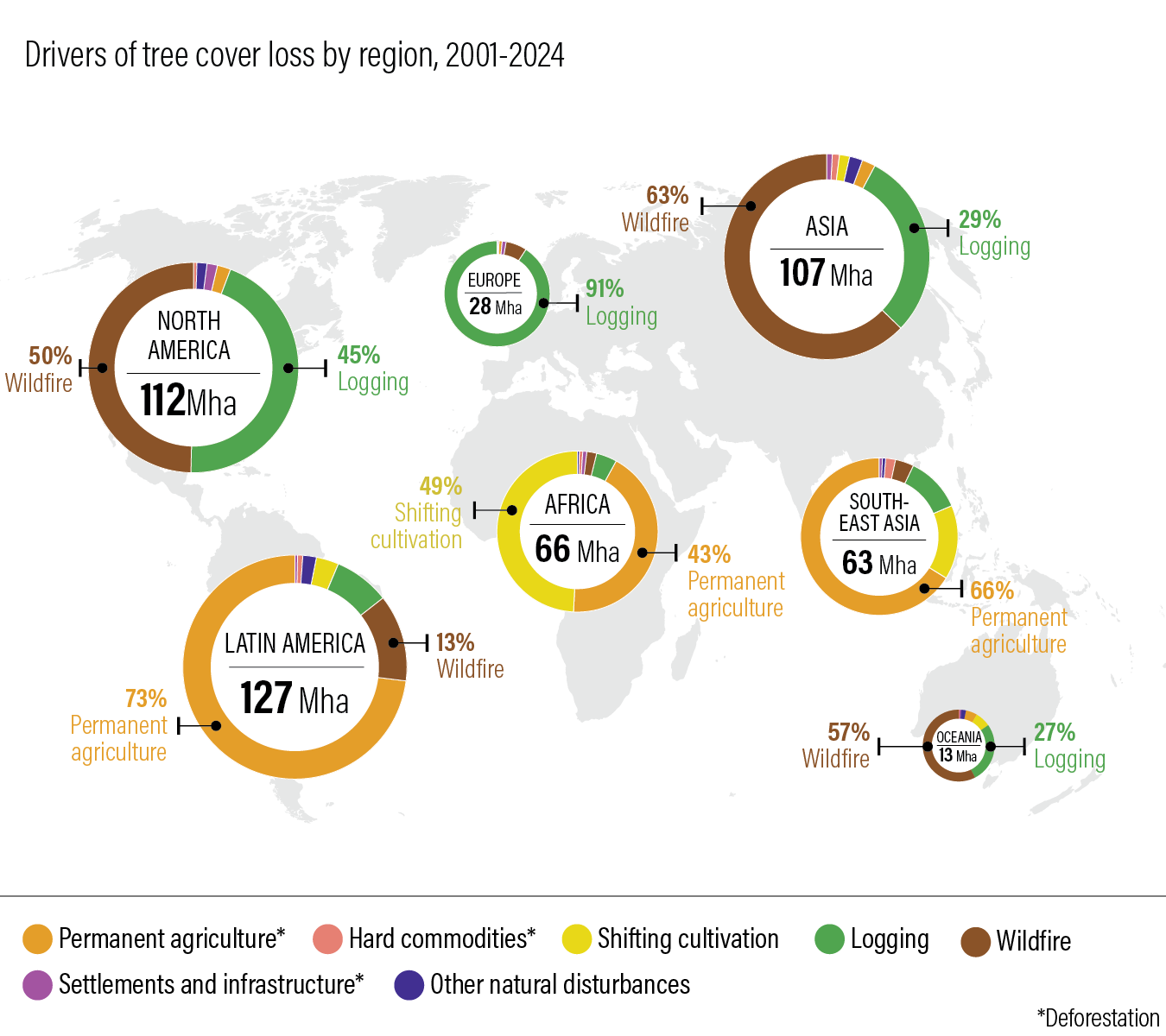

From 2001 to 2024, logging was associated with 131 million hectares of tree cover loss. (World Resources Institute)

Walmart has set a goal of zero deforestation by the end of 2025. It uses the “THESIS Index” to help suppliers track benchmarks and take action on sustainability issues in their supply chains. Walmart also has a Regeneration of Natural Resources program that has donated $65 million for the management and restoration of 50 million acres of land and one million acres of ocean. In 2024, the Walton Family Foundation, created by the family that owns Walmart, awarded $106 million in grants to protect U.S. rivers and oceans and the local communities that depend on them.

These donation amounts may seem high, but they’re abysmally low for the largest corporation in the world. Walmart’s revenue totaled $548 billion in 2024, and its profit was $16 billion. The Walton Family Foundation’s conservation grants amounted to only 0.7 percent of Walmart’s annual profit. It’s inconceivable that the company is anywhere close to mitigating its environmental impact. Walmart was not responsive to requests for comment.

Another conservation-funding megacorporation, BlackRock is the world’s largest asset management company, managing over $11 trillion in assets. The BlackRock Foundation’s mission is explicitly pro-growth: “Society needs today’s companies to create economic growth that benefits all stakeholders.” BlackRock is the largest investor in corporations driving deforestation in the Amazon rainforest. It invests in the expansion of oil operations and the production of wood chips, soy, and beef, which are top culprits in rainforest deforestation.

On the other hand, BlackRock donated $589 million in 2020 to “the firm’s social impact efforts to advance a more inclusive and sustainable economy.” An unspecified amount of this donation went to the One Acre Fund to test and scale tree-planting as a backup source of income for smallholder farmers in Africa and India. According to BlackRock, it planted 20,000,000 trees through this initiative. BlackRock profited $4.9 billion in 2020.

You be the judge: Are Walmart and BlackRock committed to social impact and sustainability or to improving their image for even higher profits?

Leading Conservation Foundations Embrace Growth

Deforestation can cause irreversible damage to complex ecosystems. (Adobe Photostock)

Despite its dubious ties to corporations, Conservation International has made laudable strides in increasing supply-chain sustainability via its Fashion Pact and Nature Positive Economies programs. Nature Positive Economies works with Indigenous peoples and communities to conserve 414 million global hectares by supporting “sustainable enterprises.” It also works with partners to address agricultural expansion, the largest source of deforestation. However, the enormous environmental impact of its corporate funders remains a blind spot for Conservation International.

The Conservation Fund also embraces a green growth vision. The NGO claims to have conserved more than one million acres of high-conservation-value forests and 2,500 miles of streams. How does this compare to the deforestation corporations engaged in to generate the money they donated to the Conservation Fund?

Addressing the Contradictions

The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) accepts money from corporations with some of the worst environmental offenses. The NGO attempts to mitigate its donors’ impacts by working with corporations to reduce their emissions, procure certified supplies, reduce deforestation, and more. This is an admirable effort to get in the mud pit and make change where it’s most needed. Unfortunately, many corporations have failed to meet their goals or cancelled their programs with WWF.

The Sierra Club Foundation takes a markedly different approach. Former Director, Michael Brune, spoke about a past funding conflict of interest:

“I learned that beginning in 2007 the Sierra Club had received more than $26 million from individuals or subsidiaries of Chesapeake Energy, one of the country’s largest natural gas companies…We were also hearing from scientists and from local Club chapters about the risks that natural gas drilling posed to our air, water, climate, and people in their communities. We cannot accept money from an industry we need to change.”

Sierra Club members perform conservation service work in Big Sur, California. (Lori Rice, Sierra Club)

The Sierra Club Foundation funds the Beyond Dirty Fuels and Shifting Trillions (to renewable energy) campaigns. The Foundation has a gift acceptance policy that prohibits donations from “recognized major polluters” or sources that make or sell products that are “unusually damaging” to the environment. Its investment policy also prohibits investments in fossil fuels and screens companies for ESG alignment. Though Sierra Club hasn’t taken a macroeconomic stance against the green growth narrative, it at least maintains some “sectoral integrity.”

Among foundations birthed from corporations, the Hewlett Foundation of the Hewlett Packard Corporation (HP) stands apart in three ways:

- The foundation has an Economy and Society Program focused on exploring economic systems change, with an explicit aim to replace neoliberalism.

- It has one of the largest environmental grantmaking programs in the US, offering $240 million in environmental grants in 2024.

- HP, a leading producer of printer paper, partners with the WWF to make production forests more sustainable. It claims to have conserved more than 500,000 acres of some of the world’s most endangered forests.

500,000 acres isn’t much compared to the amount of forests lost each year—six million acres from climate-change-induced wildfires alone since 2001. That said, HP has some of the most aggressive sustainability policies in the industry. It is one of the few companies to achieve a “net-zero impact” on deforestation from its paper and paper-based packaging. This is thanks to HP’s ambitious circular economy model, which has led it to be a major buyer of recycled waste in California. However, most of its recycled printer paper is only partially recycled, and of that recycled content, only 10 to 30 percent comes from consumer (as opposed to industrial) waste.

More importantly, economies are ultimately triangular, not circular. They have a broad base of agricultural and extractive activity, the surplus from which enables all other economic activities. Not all economic activities are conducive to recycling, and no recycling is free from its own energy and material requirements. Recycling plays only a modest role in sustainability, which ultimately is about scale, or the size of the economy relative to its containing, sustaining ecosystem.

Committed to divesting from their fossil fuel past, the Rockefeller Foundation and Rockefeller Brothers Fund finance thoughtful conservation efforts. They support shifting away from GDP towards human and ecological wellbeing as policy north stars, as I learned in my previous role at the U.S. Wellbeing Economy Alliance.

Some members of the Rockefeller family have donated to transformative economic programs—notably the Schumacher Center for New Economics. Despite being critical of unfettered and inequitable capitalism, the Rockefeller Foundation still embraces growth. This is a notable contradiction for its Big Bets climate program.

No More Destroy-and-Restore

While one or two of these foundations openly question the dominant economic model, none of them acknowledge limits to growth. Conflict of interest discourages foundations from supporting initiatives meant to stop the industrial sources of deforestation, climate change, and biodiversity loss. What’s more, it’s difficult to compare the destruction caused by corporations with the restoration funded by corporations, because corporations are hardly transparent about their environmental impacts. When questioned, they deliver cookie cutter public relations lines about their sustainability programs.

Conservation International recognizes the perverseness of the destroy-and-reforest/restore conservation method, at least from a climate change perspective. Scientist Allie Goldstein, who co-led the organization’s research on irrecoverable carbon, explains that, “In order to stem catastrophic climate change, irrecoverable carbon needs to remain stored in rainforests, mangrove forests, peatlands and other ecosystems. Humanity simply can’t afford to destroy these places.”

The Congo Rainforest, the most important rainforest carbon sink in the world, is inhabited by bonobos, which live only there. (DBeaune, Wikimedia Commons)

Wildlife populations have precipitously declined 75 percent in the past 50 years. We don’t need more greenwashing, half measures, and net-zero-by-2050 plans. “Sustainable yield” of renewable resources is still a valid concept, connoting harvest levels that Nature can keep up with. But we need zero (not “net-zero” in carbon terms) deforestation in an economy that prioritizes conservation. Even if foundations were to boldly fund steady-state economics, they’d be fighting for a Pyrrhic victory as long as the funds come from ecosystem destruction.

Sometimes you have to change the system from within. Corporate funding will undoubtedly be necessary for the land purchases, environmental regulations, and economic policy reforms necessary for true conservation. However, these projects won’t compensate for the ecological losses their funders cause, so new funding and business models will ultimately be necessary.

Independent from corporate funding, civil society must advocate for limiting economic growth as a more effective conservation strategy. In the long term, it is the only effective conservation strategy. As Brian Czech has often stated, “Conservation is a steady state economy.”

Kali Young is a development manager at CASSE.

Kali Young is a development manager at CASSE.

While I agree with most in this article, I find that it mix up “deforestation” and logging. The problem with logging in Europe is not deforestation as trees are re-planted. The loss of biodiversity is the real problem with logging if it is old growth forest. Monoculture plantations AFTER logging is the main problem if the forest was a typical “production forest” e.g in Sweden, where I live. In general, the “planting tree” narrative has little to do with conservation. Planting trees is not much better than planting corn if it is in plantation forestry. In Sweden >400 million trees are planted every year, but almost all of them are spruce or pine in plantations. It is actually better NOT to plant trees from a biodiversity perspective under Swedish condition as you will have natural regeneration.

Logging old-growth forests and replacing them with plantation timber is an example of deforestation. A forest is a complex ecosystem. A plantation is not, and therefore not a forest. I never refer to tree plantations as forests. They are no more forests than a field of wheat is a grassland.

Thus, logging is deforestation.