Defending the Last Green Valley

by Dave Rollo

The Last Green Valley, containing Connecticut’s Quiet Corner, is still “dark at night” (NASA Earth Observatory/NOAA NGDC).

The Northeast Megaregion, also referred to as BosWash, extends from Boston to Washington, DC, and is populated by more than 55 million people. It is the largest contiguous urban area in the United States. BosWash has the largest population of the eleven U.S. megaregions, which together hold over 76 percent of the nation’s population. BosWash has the highest GDP of any megaregion in the world at some $3.75 trillion. At night, BosWash and other megaregions can easily be seen from space as bands of light spanning hundreds of miles.

Yet there are some oases in the megaregion. The New Jersey Pine Barrens, for instance, remains a wilderness of over a million acres of forest, plain, swamp, and wet meadow habitats. Due to its acidic, sandy, and often waterlogged soils, the Pine Barrens was never developed.

The “Last Green Valley” of eastern Connecticut and southcentral Massachusetts is another notable exception to the development of the Northeastern Seaboard. Comprising over 700,000 acres and populated by about 300,000 people, the area is 84 percent farmland, forests, and wetlands.

The Last Green Valley is “green by day and dark by night,” goes a local saying. The area’s preservation is a product of topography, unique history, and the foresight of communities to protect their region from growth.

A Natural Conservation Corridor

The Last Green Valley extends from Connecticut’s so-called Quiet Corner of northeastern counties, northwards into Massachusetts and southwards toward the Connecticut shoreline. The Shetucket and Quinabaug rivers run through the Valley and converge to form the Thames River. Congress dedicated The Last Green Valley as the fourth National Heritage Corridor (NHC) in 1994 (there are 62 NHCs today).

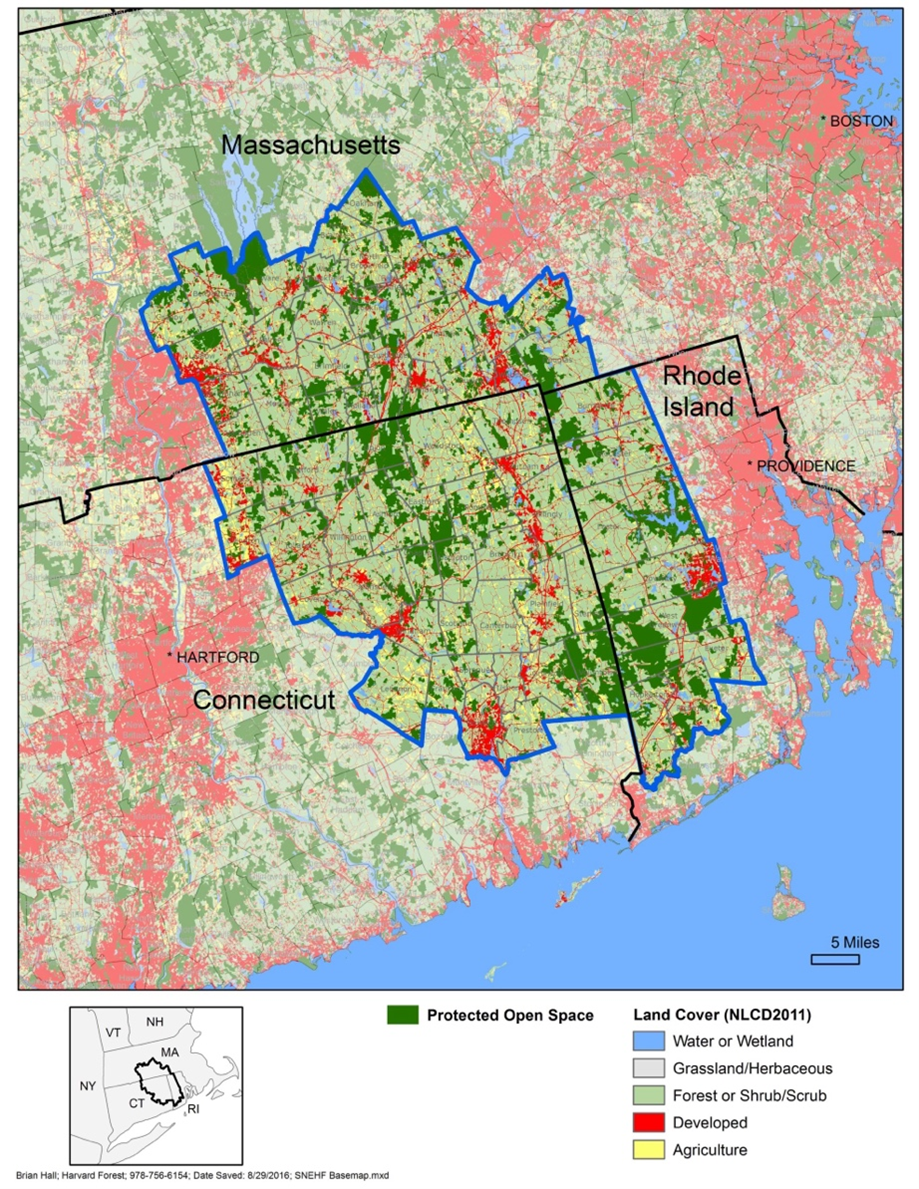

The Last Green Valley, in green, comprises 26 Connecticut and 9 Massachusetts municipalities (map courtesy of http://thelastgreenvalley.org/). The Thames River Watershed is outlined in blue.

The Last Green Valley NHC is home to 35 municipalities, three-quarters of which are in Connecticut. A non-profit, member-supported group called The Last Green Valley Incorporated (TLGV, Inc.) manages the NHC. TLVG, Inc. has worked since the inception of the NHC to protect and preserve the cultural, historic, and natural attributes of the corridor.

The Last Green Valley NHC lies within the Southern New England Heritage Forest (SNEHF). SNEHF is the largest contiguous forest tract in Southern New England, consisting of nearly 1.5 million acres. Fragmentation, or the breakup of habitat due to human development, endangers this biological hotspot. Fragmentation is a known driver of biodiversity loss, and maintaining habitat integrity is thus a high priority for TLGV, Inc.

What it Takes to Preserve Heritage

NHCs are not federally managed, but instead administered by states, counties, or non-profits. TLGV, Inc. is the designated administrator of The Last Green Valley NHC and coordinates its funding. Though the NHC designation is maintained in perpetuity, funding renewals occur periodically through acts of Congress.

These funding renewals require regular evaluations by the Department of the Interior, which assesses progress towards the legislative goals of preserving historical and cultural assets and conserving the natural resources of the valley. TLGV, Inc. issues regular reports with updates on progress toward these goals.

One goal attached to funding renewal is the “promotion of economic development.” The region must pursue this goal strategically to avoid threats to biocapacity. Art, cultural, and agro-tourism can be important means to build a sustainable and self-reliant economy. Tourism is a primary component of the economy in The Last Green Valley NHC. According to Fran Kefelas, Assistant Director of TLGV, Inc., the tourism sector has not degraded the region’s rural character. Indeed, TLGV, Inc. recognizes protection of the land and rural nature of the communities as fundamental to local economic flourishing.

TLGV, Inc. uses its funding for innovative approaches to conservation. For example, it developed and curates a GIS-based land mapper that details watersheds, trails, and blocks of natural land. According to Fran Kefelas, when the mapper became available, its utility and value were immediately evident; “It indicated that there was more forest and farmland than was initially estimated—the total rose from 77% to the 84% undeveloped land that is recognized today.”

The Last Green Valley and The Quiet Corner lie within an unfragmented forest, the Southern New England Heritage Forest (SNEHF). The SNEHF is one of the largest remaining in New England.

One of TLGV, Inc.’s primary goals is to maintain the corridor’s contiguous forest. Kerfelas describes two efforts to preserve and protect the SNEHF: 1) purchasing undeveloped tracts of land using land trusts such as Joshua’s Trust, and; 2) forest legacy projects that offer grants to land owners to manage and preserve their woodlands. Supported by 18 partners, TLGV, Inc. administers a $6.1 million program for private forest management and bird habitat assessments. Educational materials and programs are also a regular part of the organization’s efforts. It aims to engage residents in appreciation of the exceptional ecosystem in which they live.

Economic History and Geography Benefit Preservation

Historical structures dating from the colonies dot the open fields and deep forests of The Last Green Valley NHC. Homes commonly display plaques dating from the 1600s. The Quiet Corner has an abundance of these historic small towns. Their still-intact village squares and town greens enhance their charm. Putnam, for instance, has preserved its historic town center, which boasts thriving shops, art galleries, cafés, and restaurants. The National Park Service lists over 30 significant cultural points of interest within The Last Green Valley NHC; a testament to the rich history and cultural heritage of the corridor.

The economic history of the region has played a significant role in maintaining The Quiet Corner’s rural nature. Aside from farming and timber, economic development in eastern Connecticut came from waterpower. The state was a center for textile and thread mills from the mid-1800s until the latter half of the 20th century. The mills flourished with readily available hydropower from fast-flowing streams and rivers.

Hazardous millwork set the stage for workers to organize for better conditions and higher pay. As a consequence, and as hydropower was replaced by fossil fuels, southern states became attractive for relocating the industry. Thus, over much of the last century, the mills moved away. They left an economic vacuum that directed sprawl from the post-World War II boom elsewhere.

As Fran Kerfelas describes, this historical happenstance provided an interim period to work on protection of the historic and natural heritage in The Quiet Corner and The Last Green Valley NHC. Preservationists repositioned the area to utilize its intact farms and forests for tourism. This served as a basis for developing the local and regional economy. Kerfelas observes that “the lull in economic activity coincided with a surge in environmental preservation awareness.”

In the late 1980s, a group of activists from the Quinebaug River Association, with the support of Congressional Representative Sam Gedjenson, developed legislation to create the Quinebaug-Shetucket Heritage Corridor (QSHC). This corridor later came to be The Last Green Valley NHC.

Long Pond, Thompson, Connecticut (Doug McGrady, Wikimedia Commons).

The geography of eastern Connecticut has also helped to maintain its rural character. Jo Ann Reynolds, a Windham resident who holds an M.S. in landscape ecology, explains that the “topography of the state displays a marked difference between the flat Connecticut lowland plain and the highlands of the east. The long, rugged hills running along north-south rivers of the east presented obstacles to east-west road corridors—it kept our area isolated for a long time.”

Just as poor soils were an impediment to settlement in the New Jersey Pine Barrens, the rugged terrain and unique topography of The Quiet Corner (and The Last Green Valley NHC as a whole) allowed a reprieve from the rapacious sprawl on the East Coast.

A Historic Regional Community Compact

Yankee independence is legendary in Connecticut. Reflecting this independence, the state has had no effective county governance since 1960, when county jurisdictions were eliminated. Instead, Connecticut’s 169 municipalities enjoy home rule governance of their domains, tolerating only cooperative associations for large-scale planning. Proposals to merge towns have often met with fierce resistance. Even a proposal to merge smaller school districts in 2019 was shot down by the public.

When the state legislature proposed zoning changes to allow accessory dwelling units (ADUs) as a means to increase density, they made certain to allow towns to “opt out” by a two-thirds town council vote. Subsequently, at least 115 Connecticut municipalities opted out. And nearly all the towns within The Last Green Valley NHC rejected the state statute, wishing to retain local zoning control.

Given the Yankee penchant for autonomy, it is a remarkable success that in 2002 all 35 towns within The Last Green Valley NHC signed a community compact that, while not binding, expressed their commitment to Vision 2010, the area’s first comprehensive planning document. The towns’ commitment included “protecting and enhancing the nationally significant resources of the National Heritage Corridor” and “sustaining and connecting diverse habitats and rural landscapes throughout the National Heritage Corridor…” These goals are also evident in the communities’ Plans of Conservation and Development. Putnam, Connecticut’s plan, for example, emphasizes rural preservation.

According to Elaine Sistare, Town Administrator for Putnam, the community compact provides not only a shared commitment to conservation, but also a means for communities to receive funds to maintain rural character. “Too often, due to our low population, we are overlooked by Hartford (state government). By banding together, and with the help of TLGV, Inc., we receive resources to help develop and conserve our communities.”

A Sustainable Vision for the Future

Subsequent to Vision 2010, TLGV, Inc. completed the first sustainability plan for any National Heritage Corridor: The Trail to 2015, A Sustainability Plan. The latter was followed by the current Vision 2020, The Next Ten Years. Vision 2020 components include Stewardship, Land Use, Economy, and Culture and have corresponding strategies to achieve or maintain them.

Many of the strategies are aligned with a steady-state economic approach to development; directing movement towards self-sustaining, re-localized economies. Examples include:

- Support locally-grown, locally-produced products, and locally-provided services. (Stewardship)

- Advocate for a sustainable and expanding agricultural economy. (Economic Development and Community Revitalization)

- Encourage working farms and forestlands, offering economic opportunities, food, fiber, and forestry products to residents of The Last Green Valley and surrounding communities. (Land Use)

Furthermore, strategies found within the Culture section are intended to develop and maintain a preservation ethic and appreciation of place:

- Assist in the preservation of and access to cultural resource documents and oral traditions pertaining to The Last Green Valley.

- Develop school curricula and student experiences at all grade levels that communicate the significance of the cultural resources of The Last Green Valley.

This is only a sampling of the 10 vision topics and over 80 strategies in the report for TLGV, Inc. to fulfill in coordination with its 18 organizational partners, 35 municipal governments, and 300,000 residents. Furthermore, TLGV, Inc. has expanded its mission to include much of the Southern New England Heritage Forest. As described in Vision 2020, the organization sees the overlap of the forest with the Thames River Watershed as an eventual part of its service area. TLGV, Inc.’s growing service area even extends into Rhode Island.

A vision held by a handful of activists nearly forty years ago has grown into a regional movement of dozens of towns and significant areas of three states. It serves as a model for local, regional, and federal cooperation for the preservation of history, culture, and nature. The Last Green Valley NHC’s dark skies offer a bright hope and an example that other communities can follow to defend their green valleys from the growth juggernaut.

Dave Rollo is a policy specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

Sounds encouraging. I’d be curious to know how Whippoorwill, Nighthawk, and Chimney Swift populations are doing in this area–and Chuck-will’s-widow, if they occur there.

Thanks, Dave for sharing this. Very interesting and, I agree with David Whiteacre, encouraging. What I find, a bit disturbing is the ultimate control( via funding) by the Federal government which might be strongly influenced by growth minded lobbyists and legislators. We have commodity-for profit driven economy and this means growth becomes an “imperative” that can derail these needed local initiatives. And preservation of these areas as “national heritage” could be viewed as merely preserving animals in zoos or as national parks. But my thinking might be way off base. Any thoughts?

I was so excited to find this article! In 2015, I joined a group of people who were concerned about a plan that the State of Connecticut was considering, that would place a State Police Gun Range next to Pachaug Forest, the largest State forest Connecticut has. The land is partially surrounded by the forest and is practically in the middle of the greenway. We organized ourselves and created a non-profit called “Friends of Pachaug Forest”. There is definitely strength in numbers, and with the help of supportive groups such as “The Last Green Valley” we were able to hold them off till the Governorship changed hands and the plans were called off. “Friends” is still very much in existence, and the fight goes on to protect our lovely forest!!