Greenwashing in the Amazon: Debunking False Green Solutions

by Mauricio López

The concept of greenwashing has gained unfortunate relevance, especially regarding the energy transition. Greenwashing occurs when companies, governments, or institutions promote products, services, or projects as ecologically responsible, while minimizing or hiding their negative impacts. The inhabitants of the Amazon, particularly Indigenous peoples, are witnessing how greenwashing is not only problematic from an environmental perspective. It is also detrimental to human rights and social justice.

Renewable energies, such as solar, wind, and hydroelectric, are urgent solutions to the climate crisis. However, their development has not been without controversy. While these projects are presented as ecological alternatives, the consequences of their implementation in the Amazon reveal a complex paradox.

This part of the village of Boca Sanibega, home to Indigenous Ashaninka people, would be flooded by the Pakitzapango Dam, a proposed hydroelectric project in the Peruvian Amazon. (Tomás Muñita, Flickr)

The expansion of “clean” energy projects, including mining for transition minerals, into Indigenous territories and sensitive ecosystems creates serious conflicts. Developers often carry out these projects without prior, free, and informed consultation with Indigenous peoples.

This demonstrates the fundamental flaw with mainstream “green growth” rhetoric. All economic activity depends upon natural resources, and in a full world, all natural-resource extraction impacts one community or another. We need renewables to combat climate change, but climate change isn’t the only issue we face. Governments and individual consumers, particularly in high-income contexts, should also strive to decrease overall energy use. If we are to build a society of inclusion rather than exploitation, the renewable energy we do use must be developed with Indigenous peoples at the center of the decision-making process.

Clean Energy Hides Conflicts

In the Amazon, decision-makers fail to consider or intentionally hide the social and territorial impacts of clean energy projects. These projects not only negatively affect biodiversity but also impact the ways of life, organization, and worldviews of Indigenous peoples.

Hydroelectric projects in the Amazon, such as the Belo Monte project in Brazil, are paradigmatic of this practice. They are presented as “clean solutions,” but hidden behind them are the forced displacement of Indigenous communities, the destruction of their territories, and the disruption of their traditional ways of life.

Raoni Metuktire speaks on a European stage against the Bolsonaro administration’s threats to the Amazon. (Sérgio Lima, Flickr)

Many Indigenous people are determined to resist any advance of mining and large hydroelectric projects carried out without their consent. Indigenous leader Raoni Metuktire, a member of the Kayapo people, has embodied this resistance. But renewable energy projects, including mining for transition minerals, threaten countless Indigenous people and communities.

Concrete examples of the negative impacts of mining related to the energy transition are provided by a 2020 report on mining in the Amazon. Multinational companies that mine lithium, copper, and cobalt—minerals key to electric vehicle batteries—are degrading the region and its rainforests. This mining has a smaller impact, in terms of CO2 emissions, than the fossil fuels it offsets. However, mining’s effects on biodiversity and Indigenous peoples are devastating.

Mining, Energy, and Rights: An Unsustainable Model

Corporations and governments frame the mining that fuels the energy transition as the way of the future, different from traditional extractive models. However, this mining—like all mining—requires unsustainable practices that affect Indigenous territories and cause irreversible damage to the environment.

Some of the most heartbreaking testimonies come from the Indigenous peoples of Peru, where illegal mining and large mining companies are irreversibly impacting ecosystems. In addition to being vital to global climate balance, these ecosystems are the ancestral home of Indigenous peoples, such as the Asháninka and Shipibo.

Author Mauricio López works to understand the perspectives of, and challenges facing, Indigenous peoples in the Amazon. (author’s photo)

In recent decades, Peru has been the victim of the expansion of illegal gold mining. However, clean energy projects, under the pretext of mitigating climate change, have also affected communal lands. Examples include the Chinese-owned Las Bambas copper mine, which produces two percent of global supply for the clean energy transition, and the Pakitzapango hydropower project.

I have had many conversations with Indigenous leaders in which they’ve expressed grave concern about the acceleration of deforestation in key areas of the Amazon. These leaders denounce “clean” energy projects that are implemented without considering the consequences for the environment and local communities. Such projects perpetuate a development model that dispossesses Indigenous peoples of their lands and resources.

Integral Ecology: A Call to Ecological Conversion

Pope Francis, in his encyclical Laudato Si’, calls for society to embrace “integral ecology.” This approach to ecology promotes an understanding of the interconnections between ecological crisis, social injustice, and cultural degradation. Such a holistic approach would enable us to review and rethink energy projects in the Amazon.

The Catholic Church’s call for an ecological conversion challenges greenwashing. We need an authentic energy transition that does not ignore Indigenous peoples or local communities but rather places them at the center of decision-making.

Indigenous peoples have historically been the custodians of the Amazon. Their development models are based on sustainability and respect for the land. These peoples have developed sustainable natural resource management practices that align with the principles of integral ecology.

Indigenous peoples’ resistance to mining projects and large hydroelectric infrastructure is not an opposition to progress. It is a defense of a way of life that has enabled the conservation of biodiversity for centuries.

Toward a Just and Responsible Energy Transition

The solution is not to reject renewable energy, but to find a development model that respects the rights of Indigenous Peoples. We cannot continue the pattern of exploitation and dispossession that characterizes the current extractive model. Some key proposals for moving toward a just and responsible transition include:

Local and community-based renewable energy: Design solar, wind, and hydroelectric energy projects with the active participation of local communities. This is the only way to ensure benefits reach the affected populations directly and that projects do not result in land dispossession or ecosystem destruction.

Local governance systems: This is essential to ensure that decisions about land use are made by Indigenous Peoples, in collaboration with local stakeholders and state authorities. Make free, prior, and informed consultation processes the norm, not the exception.

Community-led ecological restoration: Indigenous Peoples have vast knowledge of how to restore and protect the Amazon. Recognize and value this knowledge in ecological restoration and conservation projects.

Public policies that promote territorial sovereignty and social justice: Promote government policies in the Amazon region that respect the autonomy of Indigenous peoples. Push governments to guarantee Indigenous peoples’ active participation in decision-making regarding their territories.

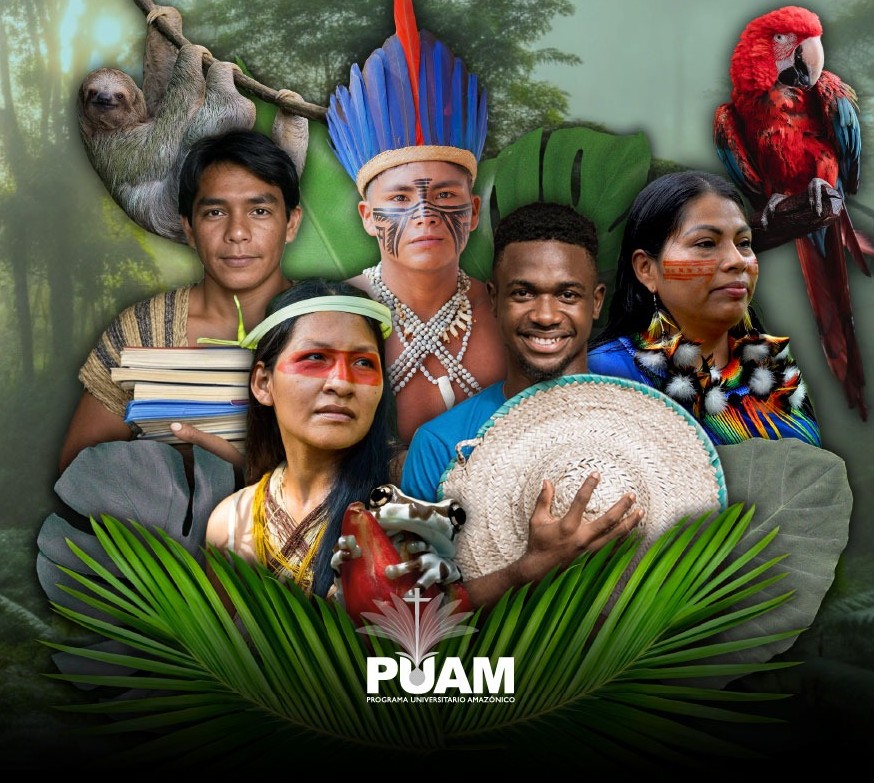

The diverse cultures and ecosystems of the Amazon represent a wealth of knowledge that can guide a true ecological conversion. (Programa Universitario Amazónico)

Reduce global energy use, toward a steady state economy: Recognize that all forms of energy production cause ecological and social impacts. Strive to decrease overall energy consumption, especially in wealthy communities, in tandem with the renewable energy transition.

Greenwashing in the Amazon is not only an ecological problem, but also a direct threat to Indigenous peoples. If the renewable energy transition is to be “just,” it must be designed in a way that respects the rights, cultures, and autonomy of local communities. Governments and developers must enable their participation and integrate their knowledge in the decision-making process.

Mauricio López is the founding director of the Amazon University Program and lay vice president of the Ecclesial Conference of the Amazon.

Mauricio López is the founding director of the Amazon University Program and lay vice president of the Ecclesial Conference of the Amazon.

We need to quit using the term ‘green energy.” There is no green energy. More like light brown energy and dark brown energy. Likewise “clean energy” should be thought of as dirty energy (useful to replace filthy energy).

Throughout the text of this article, you explain how unsustainable these supposedly “green” or “clean” technologies are, yet in paragraph 2 you succumb to greenwashing with the statement, “Renewable energies, such as solar, wind, and hydroelectric, are urgent solutions to the climate crisis.” They are not okay on indigenous lands. They are not okay on US BLM lands. They are not okay anywhere. Okay? The only okay approach to the polycrisis of converging climate, biosphere, oceanic, soil, and atmosphere degradation with drawdown of fossil hydrocarbons, all metals, and would-be renewable stocks is sobriety. Limits. Cutting back. Going on a diet. Furthermore, these greenwashed energy technologies fail to help the climate. They destroy natural carbon sinks. They require expanded power grids. They are intermittent and therefore require either fossil, nuclear, or hydro complementation. Hydro is neither “green” nor “clean” either, flooding land habitat and villages which emit methane as they decay, while destroying fish runs and forest and soil carbon sinks. These “green” technologies only benefit their manufacturers which oftentimes are the oil companies themselves. Are you really in favor of them?

Thanks for this comment, Robin. In Mauricio’s defense, that sentence was originally worded like so (as translated from Spanish by Google Translate): “While renewable energies, such as solar, wind, and hydroelectric, are being touted as urgent solutions to the climate crisis, their expansion has not been without controversy.” With his approval, I edited it (I’m CASSE’s managing editor) so there would be at least one acknowledgement that we do need renewables (my preferred phrase is “low-carbon energy”) to stop climate change. Unless you believe we should stop generating electricity altogether, renewables are a critical piece of the puzzle–ALONGSIDE decreased energy consumption!

You’re still greenwashing by not being realistic about the vast ACREAGE required for full-scale “renewables,” and are you aware of what will happen after oil production peaks, and how completely embedded oil is in their existence? Think of the diesel needed to haul just one ugly wind turbine blade up a mountain to desecrate it, and that’s just near the final stages. Before that came all the mining, smelting and factory processing of parts; it takes a lot of dense, portable energy in the field and also stationary settings.

Carving new access roads on spoiled mountains and plains is also portable-energy-intensive, as are crane operations to lift a massive wind tower & blades into position. I see relatively few Greens thinking all this through in their zeal to be the “good green guys” vs. the “bad brown (oil) guys” without realizing it’s all the same growthism. But the “green” part of it requires a lot more highly-visible land use due to its weak density.

The Amazon isn’t the best example of what “clean energy” is damaging around the world already. Hydro power is actually benign in some ways, since it at least creates natural-looking lakes. We need far more NUCLEAR power and honesty about its much smaller footprint and how reliable it is compared to wind & solar.

Renewables, by themselves, are not the solution. We also need to reduce rates of material and energy consumption. But whatever energy we do generate and consume, it needs to be renewable and sensitively established. Renewables are only intermittent locally. The wind is blowing and the sun is shining somewhere. If we can reduce total energy consumption sufficiently, we should be able to store enough energy to supply places where the wind isn’t blowing and the sun isn’t shining.

You’re merely repeating the standard spiel that pretends there’s enough acreage on this finite planet to install “sensitively established” gigantic wind turbines and black solar lakes without ruining almost every viewshed for dozens of miles around. Those platitudes simply ignore the SCALE and total acreage of these non-dense-energy projects.

Study all the landscapes that have already been blighted, then see the Princeton-Andlinger 2050 Net-Zero America projection map. It shows the vast amount of land needed for wind & solar to make a much bigger contribution, and that’s just the U.S. component. The other thing “Greens” keep ignoring is that all of that sprawl is built & maintained by oil. After oil peaks, it will start to deteriorate unless miracle batteries can ever match oil’s energy density.

This goes well beyond protecting indigenous peoples. It’s a major affront against nature that actually looks like nature, and it just adds to old energy scars like mountaintop coal mines (see photos of the Laurel Mountain, WV wind project on a very long ridge as just one example).

False Progress: Re-read my message. I said we need to reduce material and energy consumption to save the planet (i.e., reduce our energy and material demands). I never said we need to establish renewable energy to whatever levels meet our huge and growing energy demands.

I have solar panels on my roof and a storage battery. I never use anywhere near as much electricity as I generate, in part because my electricity consumption is less than half of the average one-person house (I live by myself in a small cottage). My house is fully electricity-powered (no gas). No need for wind turbines and solar farms to supply me with electricity. Like you, I think wind and solar farms are ugly. I also think that modern cities are ugly.

I am sympathetic to nuclear energy – as much as I hate it (for good reasons) – only because the human niche is so excessive and so little has been done, and too late, to confine it to the planet’s carrying capacity. As a result, we may only have wicked options to choose from. One might be: “Do we trash the planet’s climate system or save it by exploiting a possible planet-destroying energy source?”

The decisions that need to be made to save the planet for humankind’s sake are not going to be easy, or 100% safe, and will require some people (those with more than enough) to make some material sacrifice, which wouldn’t reduce their overall well-being (in fact, it may increase it!). It’s either that or an even worse alternative. Humankind is opting for the latter at this point in time, thus making it more likely that we will be left with wicked options to choose from.

If you haven’t mentioned nuclear power because you resist or fear it, expect it to become inevitable. Momentum has been growing for several years now, as reflected in the stock market.

Energy producers can see that the SCALE of “100% renewable energy” is a pipe dream and already a disaster for natural scenery, safe bird flyways and quiet rural nights. The planet would need roughly 10X what’s already blighting horizons for miles around and there’s too much rural community resistance, as there should be!

You’re well justified in calling out that contradictory wording. Industrial wind power is literally the worst visual blight Man has foisted on nature, often sticking out starkly on mountaintops. It has the visceral look of bleached, dead trees while its kinetic motion distracts from everything around it. Plus the red lights all night.

And the current SCALE of wind power is actually “small” compared to what zealots like Mark Jacobson foresee later in this century (3.8 million large wind turbines).

Apparently the Amazon basin is a poor place to catch wind, but the author fails to emphasize what it’s doing elsewhere. I see a lot of that in supposedly green treatises, since wind turbines have become a go-to icon for “replacing” the very oil that allows it them exist.

Lower-profile solar PV has also failed its potential of only blanketing roofs, roadsides and parking lots. It seeks out the cheapest acreage to smother.

“…They are intermittent and therefore require either fossil, nuclear, or hydro complementation…”

We need a lot more than complementation, you know. There’s the mathematical reality of NUCLEAR power being the only small-footprint way to replace “renewables” for electricity, especially after U.S. oil production peaks (as soon as 2027, riding on the Permian Basin). The current luxury of affordable oil props up the illusion that “renewables” can self-replicate without its portable density for mining, manufacturing, transport, installation and decades of maintenance.

More people should use the term “Energy Sprawl” as the collective problem with weaker energy sources that need vast swaths of land & water to exist. Older sprawl is seen in oil fields, strip mines, etc. but wind & solar are additive and visually far worse, especially giant wind turbines pushing kinetic starkness on some of the world’s last scenic places. If not built directly on land (or water) they’re still visible many miles away, aka in the viewshed. Since the PTC (production tax credit) was unleashed in America, especially since about 2010, I’ve been dismayed by “environmentalists” who’ve become eager land developers, directly contradicting the movement’s history. The John Muir Trust in Scotland echoes what he would be saying today.

Many of today’s Greenfolk are maddeningly selective about what they consider acceptable blight on nature. They’ll rail against hydroelectric dams while ignoring that towering wind turbines are merely air-dams, far easier to see on horizons whereas hydropower at least creates lakes that blend with nature. Big Wind is like the inverse of The Emperor’s New Clothes, and that’s on top of all the noise, dead birds, bats & insects wherever they march.

In light of Mauricio López call to wake up to greenwashing, Alix Underwood’s edit, and Robin Schaufler’s reminders of ways renewable technologies are being coopted, moves to calm constant growth and to communicate (and experience) the value in growing other dimensions of our lives—relationships, enjoyment, purposeful work—offer potential to take the pressure off all the problems mentioned. Flip the old DuPont slogan, Better Living Unplugged.

Real Progress: If you have read some of my past comments you would have noticed that, above all, I have been saying that ecological sustainability requires humankind to reduce its rate of throughput (rate of resource extraction/waste generation) so it is again within the ecosphere’s regenerative and waste assimilative capacities. I’ve been saying it, as have others, for a long time. This would be best achieved though quantitative throughput restrictions (throughput caps) best imposed in the form of restricted rights to access resources and generate wastes (permits) with a limited life-span, by a central authority, and best auctioned off by the authority. The price paid for permits would be equivalent to a scarcity tax. It would increase the cost of resource use and waste generation and encourage more efficient use of the throughput.

Because, globally, the throughput is currently 75% above global Biocapacity, this would mean reducing global throughput (Ecological Footprint) to at least 57% of its current level. It would have to been done over time, not overnight, but reasonably quickly, given our predicament. If achieved, the transition to renewables would be ecologically sustainable by the mere fact that the throughput would again be below global Biocapacity. Non-renewable alternatives would quickly become unviable. It would also induce humankind to think seriously about population numbers because it would force humankind to make a choice between maintaining per capita affluence and reducing population numbers or allowing population to increase and reduce per capita affluence. I think we know which alternative humankind would likely choose.

The bottom line is that we must reduce the macro rate of throughput to what is ecologically sustainable, and that won’t be achieved with incentives alone and reliance on the demographic transition. All micro-level progress would be overwhelmed by macro-level growth (rebound effect), as has happened over the past fifty years.

Real Progress (continued): I would also like to put to rest the notion that cap-auction-trade systems (CATS) to restrict access to natural resources and generate wastes are an attempt at using ‘market-based’ means to achieve ecological sustainability. They are not. Even some ecological economists claim that CATS are a neoclassical economic approach to the problem. Again, they are not.

The term ‘cap’ comes first in the title of the system for a reason. Right up front, the rate of throughput is capped, which is a command-and-control measure based on ecological criteria. No markets, economic criteria, or neoclassical economist in sight.

The auctioning of permits to obtain resource access/waste generation rights and the subsequent trading of the permits relies on the market to efficiently allocate the sustainable rate of throughput. That is, the system relies on the market to reduce the throughput-intensity of what would be a sustainable level of economic activity.

A lot of people don’t like the use of markets under any circumstances. These people don’t understand that modern markets are a functional requisite of a modern, technologically sophisticated economy, and that modern markets can be harnessed for social benefit if they are appropriately regulated. Again, not a neoclassical economist in sight because neoclassical economists don’t like regulation of any sort.

If some people don’t want markets involved, how do they plan to determine who’s going to access the resources and generate the wastes? Do they want inefficient and dirty producers involved? I find that a lot of these people address the sustainability and equity issues but simply ignore the allocation issue (conveniently). A properly regulated market would best determine the appropriate allocation of the rights because the inefficient and dirty producers and/or low value-adding producers would soon go bust.

Real Progress (continued): People also believe they’d have to be engaged in the permit auctioning/buying process and therefore must compete with wealthy businesses. No, they wouldn’t. Ever bought a lump of coal, a tonne of iron ore, or a saw log? Of course, you haven’t. However, you’ve probably bought some coal-generated electricity, a steel product, and a wooden/paper product. The resource extractors (resource access permits) and producers (waste generation permits) would buy the permits. Consumers would buy end-products. The cost of resource extraction and waste generation would be reflected in goods prices, where the extra cost would be passed on by the producers. Inefficiently produced goods would be priced out of the market, unless people desperately wanted them, but they’d have to accept fewer goods, which is fine if they have extremely high use value. A case of preferring a small number of useful gadgets instead of a large number of useless widgets, which is fine if it is within the sustainability constraint, which it would be given that the throughput has been capped.

A central government can use its tax powers to reduce the marginal tax rate on low incomes to compensate low-income people for the rise in goods prices, thus ensuring the system is equitable.

And if the regulated markets don’t do a perfect good job of the allocation problem (which they won’t)? We get a somewhat inefficiently allocated, but ecologically sustainable rate of throughput. Sustainability guaranteed and no major harm done. Quite simple but politically too difficult and ideologically unacceptable to many, it seems.