Happiness Matters, Even in a Steady State Economy! Part 2: Flourishing Life

by Orsolya Lelkes

Happiness matters. The quest for happiness is an elementary life force and an inherent part of steady state economies. Many fear that reducing material consumption will bring a decline in happiness. We do not like to lose what we already have. Recession and income loss tend to hurt.

On the other hand, voluntary adjustment of priorities in life may boost well-being, as a simpler life might deliver more of what many are missing: health, time for ourselves and loved ones, community, creative pastimes, arts, culture, sports, spiritual practices, and more generally, a sense of meaning. To achieve a profound transformation of societal systems, we need to move beyond analysing the causes and signs of the social and ecological crisis and beyond describing the destructive patterns of our economies. A positive narrative is essential for inspiring and motivating individual and collective action.

Connection to nature can enhance happiness. (Bonnie Gortler (3.0 BY NC ND)

Part of such a positive narrative could be “sustainable hedonism” and “flourishing life.” In last week’s Herald, I explained how we can adjust the way we seek pleasure and cultivate “sustainable hedonism” that goes beyond the egoistic, short-term, pleasure-seeking “radical hedonism,” the hedonism we may think of when hearing the term. We may all become better hedonists (a term that was not negative to its creators, the ancient Greeks), seeking pleasure without causing harm to ourselves or to others. But helpful though sustainable hedonism may be, it is not sufficient for experiencing lasting happiness. In this second part, I explore the wider issue of happiness. Based on my recent book Sustainable Hedonism. A Thriving Life That Does Not Cost the Earth (Bristol University Press, 2021), I present the notion of flourishing life and show why it may be the right approach to happiness.

Why Question our Understanding of Thriving and Happiness?

A thriving life and happiness are often approached unconsciously and without awareness, yet they deeply affect our daily experiences as well as our long-term strivings. Happiness is both personal and cultural: We feel what we feel, but our experience is deeply intertwined with the notions of the good life held by our families, communities, and society, as well as by the worldview advanced by mainstream economics.

Modern societies have embraced notions of a good life, and strategies for achieving it, that are often fundamentally flawed. The most obvious sign that these strategies are off-track is the dire state of our ecological system, the very foundation of our lives on this planet. Our personal convictions regarding success and a good life may also be far from optimal. Many of us work hard, putting forth incredible effort, yet our goal of happiness seems to evade us like a fata morgana, a mirage. Doing more of what has not worked to date is unlikely to provide a breakthrough. We need to explore the alternatives available to us as individuals and as societies.

How can we achieve lasting happiness, satisfaction, and well-being without causing irreversible harm on a global scale? What is the mindset that helps us create a better world that supports human thriving as well as ecological regeneration?

Happiness as Flourishing Life

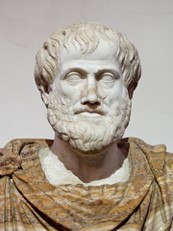

Aristotle and his notion of “eudaimonia,” often translated as “flourishing life,” is experiencing a renaissance in psychological research. It is often understood as a meaningful life, something many of us long for and whose absence brings us suffering. We wish to contribute to something larger than ourselves, we want to feel that our life matters and that we can make a difference in some way.

I argue that the notion of flourishing life has even more to offer today than it did in ancient Greece. It can be an inspiration for how to live a life that is not harmful and does not threaten future generations. It is also a life where we are powerful, because we are able to take meaningful action and we can experience our autonomy and competence in doing so.

Aristotle held that happiness cannot depend on the lucky constellation of external events, either. It cannot be the gift of gods, as it is far too precious. ‘To entrust to chance what is greatest and most noble would be a very defective arrangement,’ Aristotle wrote. This may run counter to the trust we place in chance to bring happiness: Many of us expect happiness from winning the lottery, for example, or meeting by accident the perfect partner. We may hope that fate, life or God (depending on our worldview) grants us happiness in a fair world. Aristotle, by contrast, emphasizes the role each of us plays in creating our own happy life.

Happiness is not a solo pursuit. (Bust of Aristotle, Palazzo Altemps, Rome)

Happiness—in his understanding, the activity of the soul—is based on action. Thus, we can all act and do our part. This is confirmed by recent findings in positive psychology, which holds that we can cultivate our skills for a happy life, and offers examples of how to do so: Be grateful, practice mindfulness, exercise, connect to nature, and maintain spiritual practices, to name just a few.

Aristotle goes beyond the contemporary approach of positive psychology in several ways. His notion of happiness is not an individualistic endeavor, but is relational: A person cannot be happy (or wealthy or powerful) if their gifts are not shared with friends in the community. Our happiness cannot be separated from the happiness of others. Aristotle holds the same about wealth: wealth is worth nothing if it is not enjoyed together with others.

Happiness as Soulful Action

Aristotle stands at a critical distance from desires and pleasure. Pleasure is far from the most precious thing in life, according to the philosopher; therefore he is not considered to be a hedonist.. Rather, the ultimate good is happiness, “eudaimonia,” where “eu” stands for good and “daimon” refers to a spirit. In the ancient Greek worldview, good spirits maintained the order of the cosmos. The task of humans was to create this order in themselves as well. Empirical evidence from psychological research also confirms that eudaimonic actions are conducive to health and well-being.

This sort of happiness unfolds over the course of one’s life, based on conscious actions and the cultivation of virtues. It is not simply a momentary feeling, a passing state of euphoria, but an enduring state of being. In a flourishing life, the sense of happiness arrives as a consequence of a person becoming more virtuous and living well.

Happiness comes from “the activity of soul,” holds Aristotle. We do not seek happiness directly; instead, happiness a reward that results from right actions.

Persistence in Practicing Virtues

Much of the ancient wisdom about virtues can also be adapted to our contemporary social reality. I argue in my book that cultivating the virtues of courage, temperance, good temper, and practical wisdom can yield more conscientious consumption, lifestyle adjustments, engagement in environmental action and alliances, and ultimately an increased ability to act in alignment with one’s deepest needs and desires.

Developing virtues is key to a happy and caring life. (Manfred Legasto Francisco)

A brilliant musician or a top athlete cannot be the master of their art overnight. Similarly, for the development of specific virtues, we need commitment, sustained personal effort, and a supportive community. Our schools as well as alternative education opportunities could create safe space for experiential learning, where we not only speak about our strivings for a good life, but explore our patterns and our future flourishing selves with our bodies, engaging our emotions and intuitions as well.

The arts, dance, or drama can facilitate playful explorations on serious matters. Personally, I apply psychodrama as a tool for experiential learning in groups for changemakers, who may feel stuck or who just feel that the burden of responsibility weighs too heavy on their shoulders. In the “theatre of the soul” (the literal translation of the Greek word “psychodrama”), participants recognize their power and their role in creating a thriving life for themselves and for all.

Author, in orange scarf, leading a psychodrama workshop.

In sum, I argue that the Aristotelian notion of happiness as flourishing life could reveal a way of life that leads to a state of lasting happiness without harming ourselves, others, or the planet. Flourishing life is based on soulful action, on the cultivation of virtues and wisdom. It is developed in friendships and community. Happiness is thus not simply feeling good, but doing good.

The philosophical and psychological notion of happiness can inspire our understanding, but for a profound transformation we need to explore and practice thriving in our own lives. Flourishing life could offer an alternative narrative regarding success and the good life that brings more happiness, rather than less, over the long run in a steady state economy. And while we may not find our ultimate path, this enquiry would, I argue, take us a long way toward it, leaving us and the planet better off.

Orsolya Lelkes, Ph.D. is an independent scholar and certified coach, former Deputy Director at the European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research in Vienna, and former Head of Economic Research at the Hungarian Ministry of Finance.

"Rappahannock County Courthouse" by taberandrew is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

"Rappahannock County Courthouse" by taberandrew is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

This reminds me of the guiding principles to achieve happiness according to Buddhist teachings. I am not a Buddhist, but I read a book “On Happiness” from a French Buddhist monk, Matthieu Ricard, which was quite interesting.

If I recall correctly, there were three (3) thoughts from Buddhism on happiness, as luck would have it, I can only recall two:

1). Let go of ego, don’t worry so much about how you compare to others

2) Help others – the psychic reward one gets from helping other humans is quite long lasting

Overall I think these principles are true. It’s interesting that there appears to be overlap in Western and Eastern thinking about the nature of happiness.

If only we could tell ultra-rich: a bigger yacht won’t make you happier. But a long walk in the forest probably will.

Nor am I a Buddhist but your mention of Buddhist teachings prompted me to look back at EF Schmacher’s essay, “Buddhist Economics”, from his “Small is Beautiful: a study of economics as if people mattered”. Good that Orsolya Lelkes has triggered a good discussion, pointing out the need for a positive narrative.

Thank you for your comments and thoughts.

Your reference to Buddhist teachings as well as the reference to Buddhist economics is spot on. We can learn much from this tradition

It is indeed very interesting to observe the overlap in Western and Eastern thinking about the nature of happiness and the path to it.

Interestingly, both Buddha and Aristotle talk about the “middle way” as the key (I explain it in more depth in the book).

On the one hand, I’m so glad that Aristotle is coming back into the conversation. And you do a great job of outlining the importance of classical virtues and thriving; but like most in the left/green domain, you frame it in terms of an implicit liberal individualism. It’s impossible to resurrect a virtue ethics, without a bottom-up communitarian and shared set of values reproduced through place/community bound rituals and understandings. This is well trod territory – Macintyre, Ophuls (for a radical green version). But it is not liberal nor compatible with a Kantian individualism. A virtue-ethical society would see individuals bound in covenantal relationships, joy through constraint, and ascriptive reciprocation. The opposite of the transactional, contractual, episodic nature of relationships in our disembedded (Polanyi) and now disembodied (cf trans, gender fluidity etc) late consumer society. A virtue-ethical society would be rooted in natural law. And as Macintyre came to recognize, it really only offers modernity a viable path if Aristotle is teamed up with Thomas Aquinas. The vision of green political economy that most closely aligns with this is catholic social theory and distributism. There is no ducking the illiberalism of this path. Flourishing requires consensus about basic social roles – what it means to be a mother, father, man, woman, daughter, son, elder, child. It is diametrically opposed to the unhinged culture of narcissism [Christopher Lasch, Phillip Rieff’s ‘Triumph of the Therapeutic’, Carl Trueman ‘Rise and triumph of the modern self’]. It is categorically incompatible with modern gender politics, with critical race theory, and with any vision that assumes hyper social and spatial mobility. It would embrace Pope Paul VI’s Humanitae Vitae and oppose /reverse the sexual revolution, putting marriage and families first. The “cultivation of virtues and wisdom” must be ascriptive (Christian?] It would make you v. unpopular. But it would be green.

I expect that a strong society is compromised of happy healthy responsible individuals encouraging others to see that better way. Individuals focusing on their wellbeing helps overall group well being. A relatively modern philosopher Nietzsche, on uk TV ch4 Philosophy: A guide to happiness, his view was that happiness is achieved when we overcome hardship to make worthwhile achievements. There is no happiness to be had sitting on a comfortable armchair. Its tough, but get up lifes mountain, celebrate, then try a harder one…a worthwhile happy life.

“If you want others to be happy, practice compassion. If you want to be happy, practice compassion.” Dalai Lama

A great quote!

But some of us may need some guidance how to do it…