How to Avoid the Scarcity Scare

by Gary Gardner

The thumbprint of materials excess. (Jahn Reihhard, CC-BY-2.0)

In congressional testimony last November, Isabel Munilla, an official from the Department of Energy, gave an alarming assessment of U.S. reliance on foreign minerals. For 31 of 50 critical minerals, she warned,”…the U.S. relies on other countries for more than 50 percent of our requirements…Our reliance on non-allied foreign sources for these materials is neither sustainable nor secure.” Munilla employed what we might call the “scarcity scare”—the panic that supplies of critical minerals may be insufficient for all nations to participate in the transition to clean, sustainable economies.

It is, indeed, a scary thought. Many governments, under pressure to meet the climate obligations agreed to in Paris in 2015, have made renewable energy, electric vehicles, and other low-carbon technologies central to the future of their economies. Leaving some countries out of the transition will be bad for them and bad for the planet.

It’s also worrisome if the hand-wringing around scarcity portends conflict among nations scrambling to secure supplies. Adjectives like “strategic” and indeed “critical” suggest that the minerals are worth fighting over. The Director of the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program observes that very quickly, “access to critical minerals has risen to a national security priority in the US.”

Seemingly overnight, technologies that analysts have long touted as great for greening the economy—renewable energy and pollution-free mobility—now cast an ominous shadow as sources of potential global conflict.

But are our choices so constrained? Is our future so binary: either an unstable climate because we lack the materials needed for clean technologies, or resource wars as nations fight for grams of samarium and molybdenum?

It seems to me short-sighted to insist that the glass is half empty. Sure, the situation is worrisome if we start by assuming a planet of ever-growing economies. But change the starting assumption to a global community committed to a steady state economy, and the picture brightens considerably.

The Scarcity Case

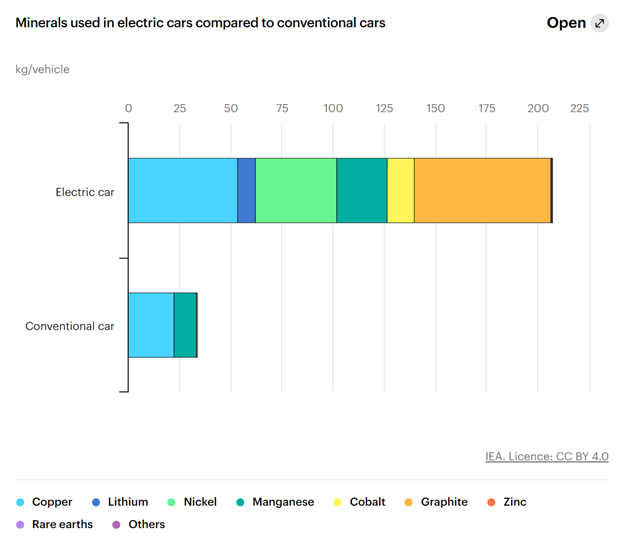

Supply concerns surrounding critical materials emerge for several reasons. First, critical minerals used in the clean energy transition are in greater demand than in economies built on fossil fuels. Consider that a typical electric car requires six times the mineral inputs of a conventional car, and an onshore wind plant requires nine times more mineral resources than a gas-fired plant, according to the International Institute for Sustainable Development.

Source: International Energy Agency

In all, the World Resources Institute reports that five critical minerals are needed for rechargeable batteries, five for electric vehicle motors, ten for wind turbines, and two for power lines. Their broad use is part of the reason they’re considered critical. The other reason, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, is that they have “a supply chain vulnerable to disruption.”

Supply vulnerability increases with growth in demand, which is what many analysts see ahead.

Supply disruption becomes still more plausible when we factor in the particular sources of supply, as critical minerals are often concentrated in a few countries. Indonesia, Chile, Peru, China, and the DRC, along with the Philippines, are the primary sources of critical materials, while processing activity is heavily concentrated in China. The concentrated nature of these supplies gives supplier nations leverage over the terms of trade.

Of course, recycling can help to augment supplies, but analysts are clear that recycling will be insufficient to meet demand. Even if we achieved 100% end-of-life recycling (which is thermodynamically impossible), recycled materials would meet only 60 percent of 2050 demand. Among the obstacles to the highest levels of recycling is the difficulty of recycling metals that are mixed with other materials. In addition, some recycling is labor-intensive and involves the use of hazardous chemicals and heat; work would likely be done in low-wage nations that may have insufficient worker safeguards.

The bottom line is that these minerals are often not abundant enough to preclude the punishing prices arising from the projected demand. The International Energy Agency estimates that supply from existing mines and those under construction could meet only half of projected lithium and cobalt requirements and 80% of copper needs by 2030. Other sources see rapidly accelerated demand for critical materials like graphite, lithium, and cobalt, ranging from a sixfold increase by 2050 (according to the World Bank) to a 20–40 times increase (International Energy Agency).

Governments React

The scarcity scare has governments on their toes. The USA, often described as resource-rich, lists 50 minerals as critical, at least ten of which are essential to the transition to a clean economy. For eight of those ten, the USA depends on imports for more than three quarters of its supply.

China is concerned, too, for similar reasons. Xi Jinping has promised to phase out production of internal combustion engines by 2035 and the Chinese government worries about the supply of key minerals like lithium, of which Australia is a major producer. In July 2023, China introduced export controls on two critical minerals, gallium and germanium, apparently to conserve its stocks. China supplies 54 percent of U.S. demand for these minerals.

| Material | Major Suppliers | Supplier share of total global supply (%) |

| Cobalt | Democratic Republic of the Congo | 70 |

| Lithium | Australia, Chile, China | 90 |

| Graphite | Turkey, Brazil, China | Highly concentrated |

| Rare earths | China | 60 |

| Nickel | Indonesia, Russia, Philippines | 55 |

Source: Edelman and World Resources Institute

Europe and the USA have also acted to secure supplies. The EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act, for example, streamlines the permitting process for mining, which has resulted in approval of Europe’s first lithium mine, in Portugal. In the US, the Inflation Reduction Act seeks to increase domestic sourcing of critical minerals for use in electric vehicles, batteries, and renewable power.

Meanwhile, supplier countries are gearing up to ensure that they get a fair share of the revenue they will earn in the scramble for critical minerals. The Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development (IGF), with more than 80 member countries, works to promote policies and regulations in the mining sector; for example, by ensuring that a larger share of mineral processing happens in the source country, and to promote international cooperation on taxation of the mining sector.

A Better Way Forward

Supply-side concerns could be significantly diminished with a reduction in demand. Yet this solution seldom comes up in discussions of the critical minerals challenge. (as googling will corroborate). Decreased demand for private electric vehicles and electricity would translate to less pressure on critical material supplies. The World Wildlife Fund suggests that a policy of curbing demand could reduce overall materials needs by more than 50% between now and 2050.

Reducing consumption begins not with sacrifice, but with eliminating redundancy in our consumption patterns. The World Economic Forum reports that 39 percent of workers globally have employer-provided mobile phones or laptops. It recommends that manufacturers configure devices to provide user profiles that sharply distinguish work and personal use. Voila! A substantial reduction in demand for phones and laptops, and the materials that power them.

Meanwhile, car-sharing advocates have long recognized that most cars spend 95 percent of their day parked, a highly inefficient use of the materials in them. In the case of electric cars (which constitute a rapidly growing share of the global fleet), these are often critical materials. Imagine every two-car household replacing one car with a combination of car-sharing, public transportation, biking, and walking. Analysts project that car-sharing alone will increase by more than 20 percent annually to 2032. Suppose this could reduce the global car vehicle fleet by 25 percent (not 50 percent, as many households have only one car). Such a shift would reduce substantially the demand for critical minerals for electric vehicles.

Is living with one car a sacrifice? Not in my case. Like many steady staters, I bike to work daily, reducing our family’s car needs to a single vehicle. Fresh air and beautiful scenery are welcome bookends to my workdays. My waistline is thinner, and my wallet fatter, because of our “sacrifice.” Would that all sacrifice were so enjoyable! Of course, occasionally my wife and I want our sole car at the same time. In those cases, we work it out, which is good for marital solidarity. In sum, I struggle to find the sacrifice in our experience.

Commuters, sans the demand for critical materials. (Kristoffer Trolle, Flickr)

Another way to reduce demand is to sign up for a subscription phone service, if you can find one. Fairphone in the Netherlands provides incentives for people to keep their phone in good condition over a long period. When it wears out, users send the phone back to Fairphone for repair, refurbishment, or materials recycling. The subscription model means Fairphone has a strong incentive to offer phones that they can easily disassemble and reuse over and over. If all phone companies (and other high-tech companies) were to use such a model, the need for minerals in electronics would surely plummet.

Finally, consider purchasing products designed for longevity. Smart phone makers today (among many other merchants) are shameless in incentivizing sales of new devices, even to owners holding a perfectly functional one (Upgrade today!). Best to help shape the market by shopping with companies that sell durable products instead. One such e-commerce site, Buy Me Once, features products that the company judges to be durable, including some electronics.

Sustainability has long held the quiet promise of yielding not only environmental and social benefits, but a precious dividend as well. It promises greater international collaboration toward a shared prosperity, and ultimately, the material foundation for a peaceful world. “Steady statesmanship in international diplomacy,” as Brian Czech called it in Supply Shock. Collaboration on building clean economies worldwide could be a robust step in that direction. But achieving this requires ending the scarcity scare, loosening our resource grip, sharing the abundance that surrounds us, and committing to the steady state economy.

Gary Gardner is CASSE’s Managing Editor.

Great compilation of research, Gary. Thank you for that. I, however, don’t see resource scarcity concerns as something to eliminate. I see them as fundamental to our understanding that we cannot continue business as usual, just powered by “renewable energy.” The resource “scarcity scare” should motivate us to undertake the behavior changes you describe (less auto dependence, more durable goods, etc.). Abundance is a great goal, but we can only get there if highly motivated to change our current “endless growth” paradigm.

Thanks, Dave. Point taken about the need to keep potential scarcity front and center. My worry is that in our society, talk of scarcity quickly morphs into fear, hysteria, demonization of rivals, and war. Those reactions are unnecessary if we reframe the problem to emphasize opportunity. Appreciate you weighing in during a busy year for you!

Thank you for this article! This is exactly what the time-poor average citizen needs, a highly readable quick read that is chock full of key insights. What I wouldn’t give to have it read aloud at the next cabinet meeting in the White House.

I do also tend to agree with Dave G.’s reply. If we collectively don’t see the answers you outline, then I suppose, in a tough love sort of way, the resource scarcity scares will do us a service by getting more heads thinking about the viability of business as usual.

As a personal insight I’ll underscore my support for one detail in particular: reducing reliance on private transportation (not eliminating, but reducing). I work for a large hospital network, and my spouse is a physician, so I hear almost daily how badly the average US citizen needs to walk or bike more. The most fantastic breakthrough drug that could be invented would be something that gets people in the US to walk two miles a day. Every medical specialist from cardiology to mental health would prescribe that.

Thanks, Cole. I like your personal insight and agree w your wise spouse! I often think we should compile a list of the dozens or hundreds of ways a steady state economy would make us all better off, to better market the concept. Walking/biking would be high on the list, I’m sure. Beyond publishing such a piece, we can also practice lifestyle changes and joyfully share the benefits of those changes with family and friends. Nothing like word-of-mouth advertising! The word would spread and maybe your spouse would be less burdened with treating unnecessary disease…

Hope all is well in the Sierra Nevada mountains (my former home)!

Wow.

So much of this myopian chit chat taking place today

it has become almost unbearable. We seem to need

this kind of opioid just to get out of bed these days.

Unfortunately the fix(es) are of a generational magnitude

and were up against the clock from a few decades to act

perspective. I don’t think the 1% ground really cares

one way or the other. Isn’t it time they picked up the

cheque and left a good tip?

Thanks, Tim. I often wonder what the post-collapse endgame will look like, by which I mean the societal response to the chaos that will then be undeniable. It’s too much to suppose that we’ll all finally agree on the cause (living beyond our means) or that we could have avoided calamity if we’d acted sooner. Some will always be in denial. Still, I am nothing if not an optimist, and I (need to?) believe that a Phoenix-like future lies ahead for humanity in which a better world will emerge. This is not to be Pollyana-ish, however; odds are that great suffering lies ahead for many people. But I think the efforts we make today to set a better course will bear fruit down the line, which is why I continue to work at it.

I’m of the same mindset, and I’m not saying that just to be agreeable. Trying to regard things as rationally as I can, and doing some mental “yes, but” gymnastics, I am inclined to agree with a Canadian fellow (Michael Barnard, who writes a lot for Cleantechnica). Overall:

– human civilization is changing in many positive ways (yay!) but not fast enough (boo!)

– most people in the 21st century will still die of natural causes

– however, many will suffer, and some will die, of things like unnecessary heat waves

– every society’s one percent will cling to power and resist change with all the force they can must. China and coal, Trump and oil, Putin and wars of conquest, Modi and growth at any cost – it’s not a pretty picture. However, rationally I predict that useful changes will come, through market forces if nothing else.

*Overall* I expect that the next 80 to 100 years will be very roughly similar in trauma and outcome to World War 2 in the last century. There will be vast suffering, and expense. However I do believe humanity will survive and our current civilization will more or less also survive (there will be continuity of record keeping, etc). As with WW2, in retrospect there will be a lot of “holy hell, that sure would have been easier if we’d nipped it in the bud early”, and so on.

For the young in particular, I would say: it is appropriate to be worried, and to be angry at my generation. However, I don’t think it’s appropriate to despair. We’ll make it – although it’s going to be a rough ride, for sure – and if good lessons are learned, and necessary changes made, a better world will result. I’m about 70% confident that life in the 22nd century will be preferable to what we experience today.

Thanks for putting meat on the bones of my reply, Cole. I am encouraged…

Hi Tim,

I like that “myopian”. But, I think some of those 1% grounders really do care. The rest, not sure, and for the whole lot, I’m pretty sure they don’t understand that a bigger pie won’t work and this is very hard to imagine since it’s so obvious to us myopians. But, there it is. Real limitations do exist, as you know. I too would love to see the 1% pick up the check and leave a good tip. Their financial situation after all comes from the rest of the working and the natural world.

A supporting detail I forgot to mention (apologies for posting a lot today!): several years ago one of the senior/managing physicians at work mentioned that 75 to 80 percent of the patient care costs in our organization go to managing four chronic diseases:

1) diabetes

2) heart disease

3) hypertension (high blood pressure)

4) depression

Every one of these chronic conditions is improved or even prevented by walking/biking a few miles to work, along with (ideally) altering one’s diet to be more compatible with a steady state economy. Our org has several million patients, so I feel reasonably confident in extrapolating this to the US population in general.

From my semi-privileged understanding of where healthcare efforts go, making a change in the direction you suggest would be a net win, even long term. Obviously we all must die of something, eventually. But from what I’ve heard, it’s the years-long, even decades long, management of chronic conditions that really burns up resources. If healthcare had to do less of that, but still had to deal with, say, a few years of more concentrated decline at the end of a typical citizen’s lifespan, that would be a huge savings to society in economic terms (and of course steady state citizens would enjoy much more of their lives in good repair).

Stunning stat, Cole, and pregnant with incredible potential, as you suggest. Dave Gardner could fashion a campaign plank out of this, I suspect.

Hi Cole,

I tend to be optimistic for similar reasons as Gary’s. One of the things I had to give up was a top down approach to cultural change. That said, it would be helpful for those who control the show( for now) step up and lend a hand or at least to get of out the way of change towards a sustainable future. I’m afraid that means radically NOT relying on those “market forces” you mention. These forces got us into our situation in the first place. “Forces” won’t work; but human beings coming together like we are doing right now to give each other practical counsel will do the job. I highly recommend looking into Edgar Cahn’s work on the use of “Time Dollars”( what I like to call “community service credits” to reform, and develop a community economics that addresses our human need for each other and a healthy respect for a natural world that sustains those communities). We need to deeply tame and control the power of money and service credits could help.

Intriguing – I’ll have to check out “Time Dollars” as you suggest.

I would add one small note, highlighting what Gary and Cole mention about transportation, and also echoing Cole’s later post about chronic diseases. Gary wrote: “Reducing consumption begins not with sacrifice, but with eliminating redundancy in our consumption patterns.” I would add that reducing consumption is increasing the joy or life. This is why the French Degrowth monthly, “La Décroissance”, is subtitled, LE JOURNAL DE LA JOIE DE VIVRE. I call this, “self-serving environmentalism”.

Like Nick Marconi, I’ve given up on top down change. Governments never lead. They may or may not follow – it depends on how much power their constituents have to vote them out of office, a power that is draining like depleted oil wells.

Yesterday, I attended a planning session for a Transition Town. (See the Transition Town Network.) I was impressed by the number of people with an intuitive feel for the necessity of a much lower throughput steady state economy, even if they lacked any conscious understanding. We are doing a multitude of actions that slightly separate us from the mainstream economy. For example, consider vegetable gardening as a radical act of self sufficiency. We can but hope that no future government will take away what little land we have with bullets or bombs.

But sometimes we are stuck at the mercy of the government. You should have seen all the sign-ups for an initiative for bicycle safety and public transportation. It’s hilly here. The steeper a section of road, the narrower, to avoid digging deeper into the hillside. Nothing like struggling up a steep section in low gear, with impatient drivers honking and zooming past.

It also troubles me how few of these really good folks, generally doing the Right Things, are willing to learn about the mineral scarcity problem, or make any attempt at systems or ecological thinking. They are all terrified of Paralysis by Analysis, forgetting that the absence of analysis is what got humanity into this fix in the first place. There are a couple of people whom I’d like to sit down with and force them to read this article, and discuss it with me, paragraph by paragraph, interrupting only to follow links to the data sources. When I speak, people act like I’m not even there, even those with similar values and concerns. You write so well! Why am I the only one I know who gets it?

Hi Robin,

Thank you for your comments. Actually, government is not the problem. But, I understand what you’re saying. We have an extremely impoverished understanding and a dangerously narrow and negative view of the political process. It’s not our fault, though. Any culture will embody a political system, no matter however dysfunctional in the long run. Politics for me just means how we deliberate on what we are going to do and why, come up with options and then decide on the means to get things done or what we need and may want. We do this all the time; but we don’t call it politics. What we need is to make this really conscious. I use the three C’s: Communication, commitment and community( the nuts and bolts) which is based on our need for one another and the natural world. Most people have been conditioned to compete with others and therefore have a very difficult time envisioning co-operative ways of living with each other, sharing responsibilities and the what we all produce together. The hard part is in finding ways to awaken this need we have for each other and the Helio-Geo-Biospheric matrix that supports us. The Transition Town Movement( you mention), the Steady State paradigm, Kate Raworth’s “Donut Economics” , Edgar Kahn’s pioneering work with time-service credits and many more are helping us make the transition away from business as usual.

Thanks for the thoughtful reply, Nick.

We have to distinguish between government and politics. Politics happens whereever there are two or more people involved. Government is formalized and carries a monopoly on force.

A government elected by the will of the people will not lead. It will protect the status quo that elected it, unless it was elected based on a platform of change. In the latter case, it may try to make change, but in America, the system of checks and balances slows down the change and alters its course, even in the best case. An autocrat can lead, but, well, then you have autocracy. There’s a spectrum in between of more or less checks and balances. For any unit greater than about the Dunbar number, removing enough constraints for real leadership risks tyrrany.

You won’t see substantial change from a government until the society has reached such a tipping point that all branches are forced to capitulate.

In the mean time, a government stuck in a system matrix that produces counter-productive results IS a problem, and may be THE problem, where government has sole jurisdiction. In my example, state, county, and municipal governments have sole responsibility for various stretches of road that are presently unsafe for bicyclists. No matter how willing Transition Town citizens are to show up with paint, striper equipment, and orange cones, we are not authorized to paint bike lanes on streets, and would risk arrest if we tried.