Ending Planned Obsolescence: A Nonpartisan Movement for Steady Staters to Support

by Rosalie Bull

“Planned obsolescence” has become a household term for 21st century Americans. No wonder, considering that most household appliances today have been designed in accordance with the practice. Now more than ever, things just aren’t made like they used to be. In fact, they’re made to fail—often within a fraction of their potential lifespans—in order to spur more consumption.

There is a growing, global movement to counter this wasteful phenomenon, and good cause for steady staters to hop onboard.

What is planned obsolescence?

Planned obsolescence is “a policy of producing consumer goods that rapidly become obsolete and so require replacing, achieved by frequent changes in design, termination of the supply of spare parts, and the use of nondurable materials.”1

The practice dates back to 1924, when the Phoebus lightbulb cartel collectively decided to manufacture lightbulbs that would burn for only 1,000 hours, despite their capacity to double or triple that time at little cost, thereby forcing consumers to purchase replacement bulbs much sooner than they ordinarily would. The scheme worked, and it became a standard profit-making formula across various sectors.

Of course, this increase in profit comes with an increase in material throughput and waste, not to mention an increased financial burden for households. And as the economy has grown, the practice has only ramped up, with companies competing to develop new forms of inefficiency and flimsiness with which to hoodwink consumers.

Light bulbs set the precedent for planned obsolescence. (CC BY-SA 2.0, Emilio_13)

Manufacturers employ many different strategies to limit a product’s lifespan artificially—from opting for less durable materials, to soldering what were once replaceable parts into the mainboard of appliance, thus limiting the scope of repairability. The tech industry is a particularly egregious practitioner. Apple, Samsung, HP, Canon, Brother, and Epson have all recently faced lawsuits in the EU for unfair commercial practices and unjust enrichment through planned obsolescence. If in 2020 you noticed your older model iPhone lagging, it’s probably because of a software update, designed to make your device intolerably slow.

The latest mutation of the trend is referred to as “perceived obsolescence,” or advertising and production cycles that make consumers feel compelled to purchase something “a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than necessary.”2 Annual automobile and smartphone models create another air of unimpeachable novelty around their latest products, despite generally introducing only slight cosmetic changes. The fashion industry has picked up on it as well, capitalizing on “micro trends” that progress from the epitome of chic-ness to utter irrelevance in a matter of months. You could even argue that the harmful proliferation of single-use plastics stems from the culture of disposability that planned and perceived obsolescence creates.

Planned obsolescence generates enormous profits for the companies that practice it. In fact, Apple makes enough money in three hours to pay the $27-million dollar fine resulting from its aforementioned lawsuit with the French government. Apple is a great example of a company that, finding their target market saturated, increasingly leans on planned and perceived obsolescence to meet the growth imperative of an outdated economic system.

They keep turning profits, while the rest of us get stuck with the waste. 59.4 million tons of electronic waste is projected to have been generated in 2022 alone, the majority of which gets shipped to developing countries that lack the infrastructure to process it. Mountains of e-waste (including household appliances) sit in open air dumps throughout the Global South, leaking toxic substances into the environment. Toss in the fashion industry’s 92 million tons of annual textile waste, also largely a product of planned and perceived obsolescence, and you’ve got, well, the world as it stands: needlessly wasteful, hyper-consumptive, profit-driven madness.

A Ban On Planned Obsolescence

None of this is news to the seasoned steady stater. But it is an opportunity.

Convincing everyday people and their representatives to adopt strategies of degrowth toward a steady state economy is an uphill battle to say the least. When confronted with ecological limits to growth, most entrenched capitalists—growthists at large for that matter—prefer outright denial.

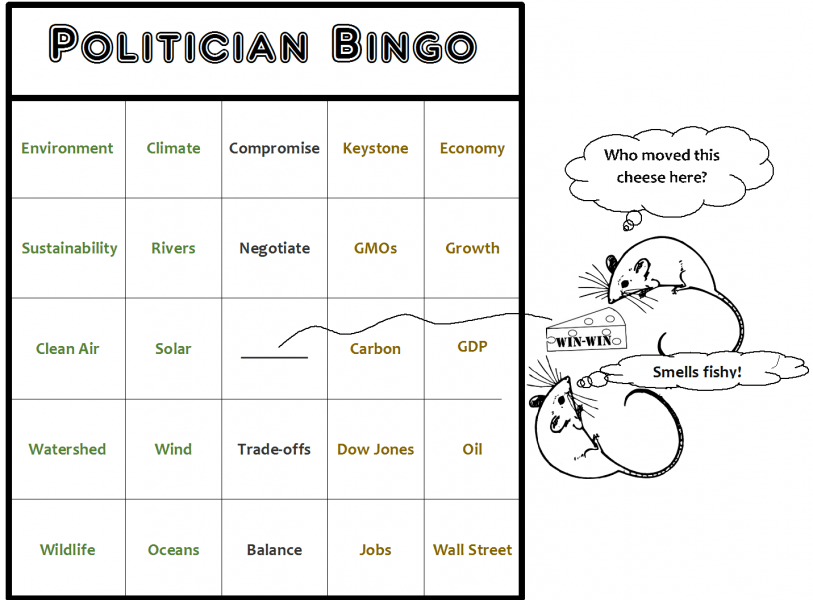

Who, aside from Wall Street and Madison Avenue, likes planned obsolescence? (CC BY 2.0, Curtis Palmer)

Ending planned obsolescence would greatly decrease resource extraction, material throughput and waste. It would slow the frenzied pace of production and give individuals a chance to reintegrate the values of thrift, repair and durability into their personal consumption frameworks. A well-executed bill could stabilize or even degrow multiple sectors of the economy (tech, fashion, transportation) in the name of consumer and environmental protection, without requiring lawmakers to promote degrowth outright.

What’s more, the legislation would put money back into consumer’s pockets and increase blue-collar jobs. We’d need more repairmen, mechanics, and tailors, and with the economy less saturated by low quality goods mass-produced overseas, local craftsmanship might once again become economically viable. Furthermore, a ban on planned obsolescence would not result in job loss, as deterrents might have you believe, since most of the manufacturing jobs in question have already been outsourced or automated.

The proposal incorporates liberal-coded climate action and environmental protection initiatives along with a certain “America first” trade logic popular amongst conservatives. It benefits small, local economies and low to middle class households. Furthermore, planned obsolescence is a common grumble with a recognizable, not yet polarized name. In short, a pushback against planned obsolescence has the makings of a widely popular, bipartisan policy.

Current Legislation to Address Planned Obsolescence and What We Need Next

A total ban on planned obsolescence would need to address the practice’s multiple variants across industries and focus on improving product transparency, durability, and repairability. This ambitious goal will likely be realized through smaller legislative victories. Indeed, this process has already begun across the European Union, and the United States has recently followed suit.

In 2013, the EU’s European Economic and Social Committee (EESC) adopted an official opinion calling for a total ban on planned obsolescence. While France is the only member country to date that legally penalizes planned obsolescence, the EESC does require manufacturers across the EU to clearly label a product’s expected lifespan in order to promote transparency. Additionally, it requires that manufacturers produce replacement parts for appliances throughout the entire length of the warranty period.

U.S. Federal Trade Commission, Washington, DC. (CC BY-SA 2.0, Scott)

In early 2022, President Biden issued an executive order directing the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to draft regulations that make it harder for “tech and other” companies to impede consumers’ ability to independently repair their products. This past July, the FTC unanimously voted “to strengthen enforcement against repair restrictions that prevent small businesses, workers, consumers, and even government entities from fixing their own products.” We’ll see how effective these measures against planned obsolescence are in the months to come.

Despite these recent advances, we’re still a long way from ending planned obsolescence. We need more aggressive and comprehensive legislation against the practice as a whole, not just its current manifestations, or else we’ll find ourselves stuck in yet another game of never ending whack-a-mole, chasing corporations through legislative loopholes until the cows come home.

Lieselot Bisschop, Yogi Hendlin, and Jelle Jaspers recently published a paper advocating that planned obsolescence should be penalized as a corporate environmental crime. This approach would halt any variant of planned obsolescence in its tracks, while allowing legislative reform to focus on incentivizing ecological robustness and social utility.

Jason Hickel suggests a few such reforms in his book Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World. Notably, he proposes that lawmakers require manufacturers to issue warranties on their products that extend throughout the “entire duration of maximum feasible lifespans.”3 Since the majority of today’s appliances and gadgets could already last 2-5 times longer than they currently do,4 we could expect the reform to decrease repeat consumption by the same order of magnitude.

Ending perceived obsolescence, with its origins in advertising, is a trickier problem that will need to be addressed w different policy tools.

Possibilities In A Post-Planned Obsolescence World?

A ban on planned obsolescence would fundamentally change the theoretical landscape around the advancement of a steady state economy. People are more comfortable with changes that exist in proximity to their lived reality. Upon having lived through a relative rollback of hyper-disposability and consumption, we may more easily entertain the idea of an economy structured around social and ecological sustainability, as opposed to the imperative of 2-3% annual growth. We could tell our friends and neighbors, “See? That wasn’t so bad, was it?”

Things can be built to last. (CC BY 2.0, Jerome Bon)

A critique of planned obsolescence carries with it a critique of capitalism’s growth imperative. It agitates the underlying assumption that “all growth is good growth” by pointing out how profits are increasingly made through manipulating and exploiting consumer demand, not through leaps in innovation and efficiency, and certainly not in service of humanity. To borrow again from Jason Hickel:

“We’d like to think of capitalism as a system that’s build on rational efficiency, but in reality it’s exactly the opposite. Planned obsolescence is a form of intentional inefficiency. The inefficiency is (bizarrely) rational in terms of maximizing profits, but from the perspective of human need, and from the perspective of ecology, it is madness…It’s like shoveling ecosystems and human lives into a bottomless pit of demand. And the void will never be filled.”5

To the extent the movement to end planned obsolescence aligns with degrowth toward a steady state economy, degrowth will align with those individuals who seek to end planned obsolescence. Though they might not (yet) articulate it as such, anti-obsolescence activists implicitly recognize that, after a point, growth for growth’s sake is neither pro-social nor efficient. It’s a bit like tricking a carnivorous friend into eating a scrumptious vegan muffin.

A successful steady-state movement will find allies and footholds in the world that we have, and will prioritize strategies that get us closer to the world we want, without insisting on a wholesale ideological leap. Case in point: CASSE has found that the major environmental NGOs are unwilling to take a position in support of a steady state economy, but several (including Sierra Club and NRDC) have made statements criticizing planned obsolescence.

Let’s organize in coordination with the movement to end planned obsolescence, and see if we can’t pick up some steady staters along the way!

1Oxford English Dictionary, ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), s.v. “Planned Obsolescence.”

2Stevens, B., quoted in Adamson, G. Industrial Strength Design: How Brooke Stevens Shaped Your World. (MIT Press, 2005).

3Hickel, J. Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World. (London: Windmill Books, 2021), 210-211.

4Hickel, Less is More, 211.

5Hickel, Less is More, 210-211

Absolutely solid strategy. There have already been some Euro lawsuit victories against planned obsolescence in the tech sector. And yes, planned obsolescence is a corporate environmental crime. I add my own 2 cents: I’ve seen car-centric suburbs where there are no people in the streets. (Kids don’t even walk to school.) By purposely & exclusively structuring communities around the car, they have made walking obsolete.

Interesting point! I was actually just in a conversation with my mom about how “workplace attire” is especially carbon intensive. Default workplace attire equates starched button downs and ironed slacks with positive workplaces values like organization and professionalism. Within the varied incentive structures of the modern office, it is common for employees to amass walk-in-closet-fulls of professional pieces: suits, blazers, trousers, ties, loafers, boots, etc. All of which require resource intensive and carbon intensive maintenance.

Any climate responsible timeline will readily recognize this error and adapt expectation and incentive structures to foster low carbon lifestyles. A single step forward might look like a law firm instituting a “wrinkle-friendly” policy to encourage employees to wear garments repeatedly between washes. Remote work obviously has its advantages in this and other emissions reduction areas.

While this does not fall within the definition of planned obsolescence, it does gesture at something in the general area—as does your car-centric suburbia. I think we might be getting at an understanding of how many facets of our day-to-day lives have been reordered in the sweeping momentum of growth capitalism. As a result, simple climate “fixes” (walk more, buy less) are barred or made obsolete to the average individual.

The exciting thing is this opens up a whole range of “consumer strategies” to add to the current climate action toolkit, beyond boycotts and B-Corps. Thus the workplace, neighborhood, school, etc may become sites of degrowth organization and action…

Thank you for this. People buying endless amounts of “cheap cr@p” is one of my pet peeves, and when people throw objects how because they can’t be bothered to even try to mend or repair them, oh man .. I am both disgusted by and pity such people.

Less stuff, of higher quality, that one takes good care of = an uncluttered, pleasant personal environment. I hammer on that point to my friends and family, and strive to lead by example.

I meant to say “when people throw objects *out* ” but was typing too fast. Apologies.

Our little borough of < 2000 households in the suburbs of Philadelphia has a zero-waste resolution. Can you direct me to ideas or resources for making that work on a local scale? We already have a farmer's market, which has a plastic bag ban, and a co-op market which requires you to bring your own bag. It's a nice start, but next steps are elusive.

Hi Robin! Woof—this stuff can indeed be so elusive.

Finding solutions that work on a community scale is my current favorite area of interest. I’m set to write another blog post here soon, and I would love to do a deep dive on some of the different degrowth/SSE resources available to community organizers.

If you wouldn’t mind answering some questions for me, it could be helpful to know the following:

How did your borough decide to move towards zero waste? What structures are in place to lead the transition? How do you articulate your vision? What are the main waste streams in/through your community? Are there any other community initiatives that might align with the movement towards zero waste? Is your community organizing across difference (race, socioeconomic status, religion, etc?) Feel free to email me directly if you’d like at [email protected]. And thanks for such a fun prompt! The blog should post within two weeks.

Instead of a blog post, here are some cool resources that I think would be helpful for you.

1. There is a nonprofit called Zero Waste Cities operating in the EU. They published a “master plan” (linked below) to guide cities in their transition to zero waste. Their whole website is chock full of resources to support your transition.

https://zerowastecities.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/2020_07_07_zwe_zero_waste_cities_masterplan.pdf

2. This is a blog post by a degrowth scholar from Maine. It is a speculative piece about the long term transition to regenerative community culture.

https://www.resilience.org/stories/2023-02-07/a-degrowth-housing-vision-for-maine/

3. Here is a “Zero Waste City Manual” that also provides a pretty comprehensive roadmap for cities committed to zero-waste.

https://www.no-burn.org/wp-content/uploads/ZWC-Manual_20200725-1.pdf

4. Here’s a link to “Zero Waste Event Planning” – which might be a good starting point for your committee.

https://www.greenbeltmd.gov/home/showpublisheddocument/18343/637527154402970000

5. Establishing a community Tool Bank is a great way to minimize waste and promote communal relation. Again, this might be a nice low hanging fruit for these early stages.

https://toolbank.org

6. You might consider establishing a resilience hub at your community center, where people can learn skills that support a circular community economy–sewing, canning, basic carpentry/repair skills. That way, you can build a base of community support and further your zero-waste goals at the same time.

https://www.usdn.org/resilience-hubs.html

Wonderful article. I hate planned obsolescence, and my passion against it grows every time I need to replace something I shouldn’t have to, and in order to do so, need to deal with a plumber, clerk, etc. who couldn’t care less. And my passion went up a huge jump the other day when a failed water heater likely contributed to a scary case of bronchitis only 13 short years after replacing the heat exchanger coils. Same with the plastic cartridge in the faucet. Same with the Android. Same with the iPhone. Same with **ANY** online user interface. I am trying to find people who care, and who want to work to build…whatever, so that things last longer. Anybody in Southern California? If not, where in God’s green earth do I go to get an ounce of hope in this regard. Because after 33 years in Southern California, it doesn’t seem to be around here.