Influenced to Overconsume: How Social Media Hijacks Sustainability

by Priya Thompson

Fashion vlogger (video blogger) atop a throne of stuff. (AI generated, StockCake)

We live in an age defined by contradiction. On one hand, the climate crisis demands urgent and systemic action. On the other hand, we are more connected to a digital world that profits—at great ecological cost—from our distraction, desires, and deeply human need to belong.

This tension is constant and personal for many Gen Z users, who overwhelmingly identify with sustainability as a lifestyle and a moral imperative. They carry Hydro Flasks, thrift instead of buying new, and share aesthetic snaps of their low-waste routines. But open TikTok or Instagram, and alongside sustainability, a different narrative emerges: shopping hauls, $300 Amazon “must-haves,” and countless “day in the life” videos centered around consumption.

This is the heart of the paradox. Sustainability is trending—but so is overconsumption. The two coexist uncomfortably, layered over each other in our feeds. Scroll far enough and you’ll find eco-conscious influencers showcasing bamboo toothbrushes beside fast-fashion hauls. Ethical products are placed next to impulse buys and algorithmically curated for maximum engagement.

The Algorithm of Aspiration

Social media platforms aren’t neutral spaces; they’re sophisticated engines of consumer manipulation. Their algorithms are designed to reward content that generates clicks, likes, shares, and conversions. What performs best? Relatable, aspirational consumption. Shopping hauls, unboxings, glow-up routines, and “what I bought this week” videos dominate Gen Z’s digital experience.

For readers unfamiliar with this experience, shopping hauls are where someone works their way through a pile of clothing on video. They try on each item and review it for quality, style, and fit. Though shopping hauls are typically associated with ultra-fast fashion, secondhand hauls are gaining in popularity. In unboxings, influencers unpack new products on camera while discussing their packaging, branding, and other features. A “glow-up” is a personal transformation achieved by improving an aspect of your life. Influencers promote a range of glow-up routines, from meditation practices to wardrobe updates and skincare regimens.

Isn’t consumer culture fabulous? (Pickpik)

This type of content pushes users to buy, not out of necessity, but out of inspiration, envy, or entertainment. Even in spaces that promote sustainability, this dynamic persists. Micro-influencers market eco-friendly alternatives with as much intensity as traditional brands. They promote biodegradable phone cases, “sustainable” yoga sets, and reusable silicone pouches through affiliate links and #sponcon campaigns.

Affiliate links are commission-based URLs that give influencers a cut of each sale generated through their content. #sponcon campaigns are paid sponsorships where influencers are compensated to feature a product in their posts. The use of these marketing methods for “eco-friendly” products reinforces a harmful message: Sustainability is just another trend, another lifestyle to buy into.

This is where sustainability loses its soul. At its core, real sustainability requires doing less, consuming less, and reimagining our relationship with the planet. When filtered through influencer culture, that message is softened and reduced. Social media makes sustainability digestible for a society that derives meaning from material accumulation.

Greenwashed and Burned Out

Consumer culture is less fabulous when its underbelly is exposed. (National Wildlife Federation Blog)

Instead of real sustainability, we get “ethical overconsumption:” the same shopping habits, repackaged in brown cardboard boxes and recyclable tape. This is textbook greenwashing—marketing masquerading as activism. It may soothe guilt or fuel a sense of purpose, but it doesn’t challenge the systems that caused our ecological quandary.

Meanwhile, the very structure of social media encourages more than just material overconsumption. It cultivates emotional burnout. The pressure to stay updated, aesthetic, and “on brand” is immense. Many Gen Z users experience what psychologists now refer to as digital fatigue, a sense of emotional exhaustion from overexposure to content, comparison, and consumer messaging.

Enter doomscrolling: the compulsive consumption of distressing or anxiety-inducing content. Climate catastrophes, economic anxiety, rising rent, political instability—it’s all just a swipe away. This constant stream of bad news fuels a sense of hopelessness, which in turn drives emotional spending.

Retail therapy, once confined to malls and storefronts, now lives in our pockets. With a few taps, we can buy relief—momentary, fleeting, but soothing, nonetheless.

This impacts our bank accounts and our planet. Each online order, no matter how “eco” the label, leaves a footprint. Packaging waste, shipping emissions, and return logistics—not to mention resources extracted to produce the item—all add up. The hard truth? There is no ethical way to overconsume.

Redefining Identity and Belonging

This is the contradiction Gen Z must face. Our generation is hailed as the most progressive, most environmentally conscious, and most digitally fluent. But we are also excessively marketed to, emotionally online, and vulnerable to the psychological patterns that drive compulsive behavior.

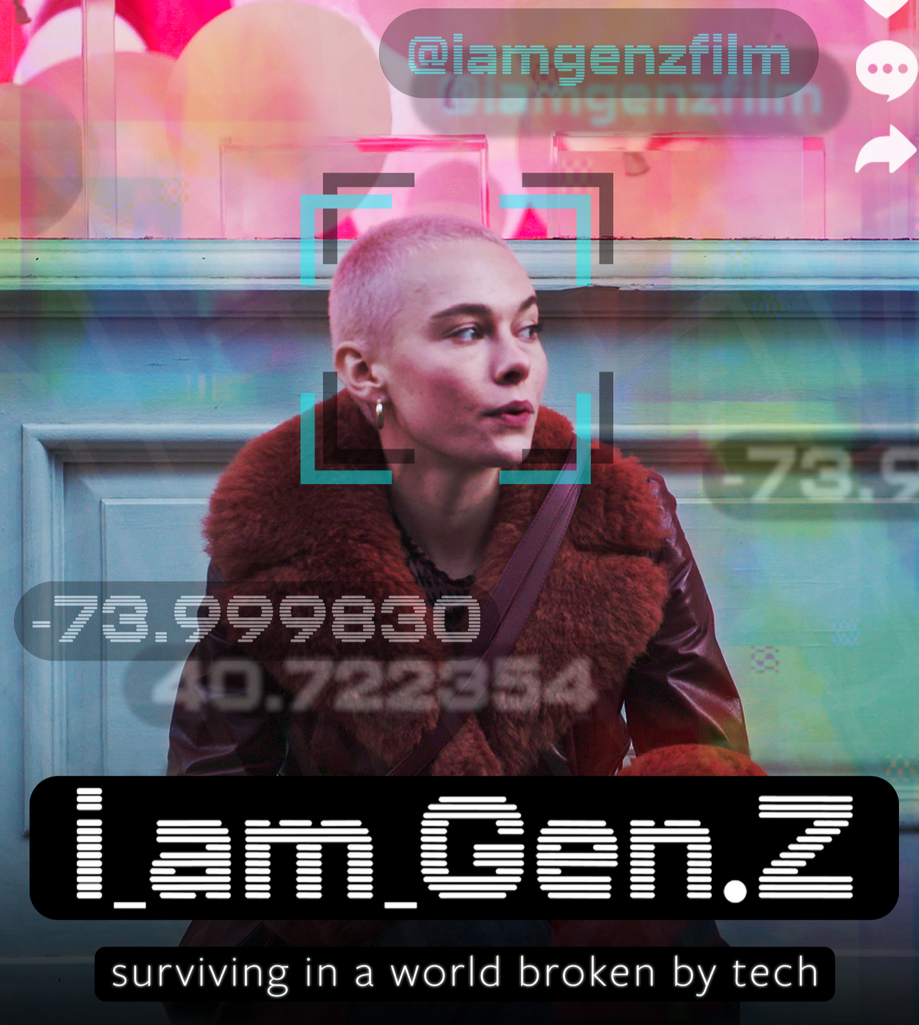

Most Gen Z-ers are still finding themselves. (Coco & Claude Productions Ltd, Wikimedia Commons)

Social media has blurred the lines between identity and advertising. Influencers don’t just sell products; they sell lifestyles. For users struggling with uncertainty, loneliness, or anxiety, these lifestyles look like salvation. A better skincare routine. A minimalist wardrobe. A matching water bottle and a Stanley cup. These items promise transformation—if only we click “add to cart.”

And yet, the dopamine fades. The packages pile up. And the cycle begins again.

To truly break this cycle, we must challenge the systems that keep us trapped. That means resisting the narrative that we can shop our way to sustainability—that more stuff, even “good” stuff, is the answer. It means recognizing that healing, whether personal or planetary, does not come in the form of new possessions.

Toward a Culture of Enough

Most young people are keenly aware that something’s got to give. (Garry Knight, The Ecologist)

It’s time to embrace intentionality. That means a digital and consumer slowdown—a reclamation of our time, our choices, and our values. This isn’t about shaming people for buying things they need, or even things they want. It’s about asking why we buy. Who benefits? What’s the cost? How do we begin to imagine a different kind of relationship with consumption?

Some influencers are already modeling this shift. Creators on TikTok, such as @michael_mezz and @sagelenier, are de-influencing the norm. Rather than pushing products, they share ideas about degrowth, anti-capitalism, community care, and ecological justice. They talk about repairing, reusing, and reframing. They show how small shifts in mindset can lead to large shifts in behavior.

Their content aligns with a broader vision of a steady state economy, where human well-being and ecological balance are more important than GDP growth or follower counts. It is a vision of a world where we measure success not by how much we accumulate but by how deeply we connect with others, our environment, and ourselves.

Choosing Meaning Over More

Of course, this cultural shift won’t be easy. We are up against powerful forces—corporations with billion-dollar advertising budgets, platforms designed to maximize our screen time, and a culture that equates buying with belonging. But we’re not powerless. Our choices—especially collective ones—carry weight.

So, what can we do? Start small:

- Unfollow accounts that make you feel like you need more.

- Pause before clicking “buy now.”

- Ask yourself whether a purchase aligns with your values or fills a void.

- Support creators who challenge the status quo, not those who profit from it.

- Reclaim boredom. Reclaim slowness. Reclaim your attention.

There is magic to behold, if you lift your eyes from the screen. (Christopher Campbell, Freerange)

Social media doesn’t have to be the enemy of sustainability. In fact, it can be a powerful ally. We can use it to spread awareness, amplify marginalized voices, and build communities rooted in care and change. However, we will only achieve these goals if we stop treating social media like a shopping mall and start treating it like a public square.

Slowing down, both online and in life, is an act of resistance. It disrupts the narrative that our worth is tied to our output, our appearance, or our possessions. It invites us to be present instead of performative, intentional instead of impulsive, and grounded instead of overwhelmed. It is these qualities that provide meaning, not the accumulation of things.

In a world teetering on the edge of ecological crisis, what we choose to pay attention to—what we click, share, buy, and believe—might just shape the future. The planet needs us to choose wisely. We need us to choose wisely.

Priya Thompson is a CASSE intern and a communications student at Marymount University.

Priya Thompson is a CASSE intern and a communications student at Marymount University.

Oh man, this is all so true. There’s really not much more I can add to Priya’s excellent article, other than to stress:

Buying stuff (dare I say, “buying cr@p you don’t need”) will not make you happy. Good sleep, a health diet, a sensible diet, and time outdoors will make one happy.

It’s no surprise that corporate market forces have utilised the socials to drive for growth comandeering and plundering our attention, our ‘life time’ in the process. Its great to hear of eco influences striking back.

Social media has all the potential to facilitate a full scale revolution away from consumerism and back to responsibility.

Modern society has enabled anonymous living. In centuries past we lived in social tribes and villages, depended on one another for assistance for survival. It was cooperate and help one another, share not steal. Thatt good turn would be returned when it was desperately needed. Irresponsible non cooperators had known bad reputations, and would have no goodwill reserve to dip into when life got desperate. Modern living does not rely on reputation for survival. Harsh winters, crop gathering, famine, tribal warfare no longer everyday threats.

Fast forward to the growth dilemma. We need to reharness the power of visible shared reputations to moderate our behaviour.Lets voluntarily implement and join apps to monitor our consumption with that consumption supporting emerging cooperatively owned business with the mission of delivering on a sustainable fair world.

Insightful and well-written. Thank you!

So well written! I’m glad that the message of less consumption is getting through in some circles. I feel like the environmental narrative has been hijacked by climate change as our only problem, probably because telling people that we all have to return to a more basic lifestyle would be far less palatable and might turn people off, so saying ‘we can still consume stuff, as long as it’s made with renewable energy’ makes it sound better, even if it’s ignoring the even bigger problems of pollution, waste, extinctions and resource depletion.

I have trouble helping folks understand why we need a ‘steady state’. I totally understand why, (mostly environmentally) but more viscerally such that I cannot explain it. Does anyone know of a concise article or talk I can study (so I am prepared to educate others)? Thank you

Thank you for this comment and question, Barbara. It’s hard to convince people that continued economic growth is harmful, given the pervasiveness of the growth rhetoric.

A good place to start is CASSE’s position statement on economic growth (You should sign it, while you’re at it, if you haven’t done so!): https://steadystate.org/act/sign-the-position/read-the-position-statement/

You can find lots of other resources by browsing CASSE’s website. For example, we have briefing papers on various foundational concepts, including this one titled “What Is a Steady State Economy?” https://www.keepandshare.com/doc19/36906/what-is-a-sse-briefing-paper-pdf-262k?da=y

For a deeper dive, I recommend reading Brian Czech’s Supply Shock: https://steadystate.org/steady-state-press/supply-shock/

If you want to branch out from CASSE, there are several organizations with similar missions. I recommend checking out the Degrowth Institute (https://www.degrowthinstitute.org/), a new org based in Chicago. They develop outreach and educational materials, including a toolkit: https://www.degrowthinstitute.org/toolkit

healthy thoughts= healthy mind, for me less clutter(inside and outside) equates to healthy thoughts . I try hard to not fall for all the blingy content that is out there in social media.

Really enjoyed reading this! Social media definitely pushes us to want more than we need. At Masters Engineering Solutions, we value sustainability and practical choices, so this message really resonates with our values. Thanks for the perspective!