Introducing the Sustainable Transportation Act

by David Shreve

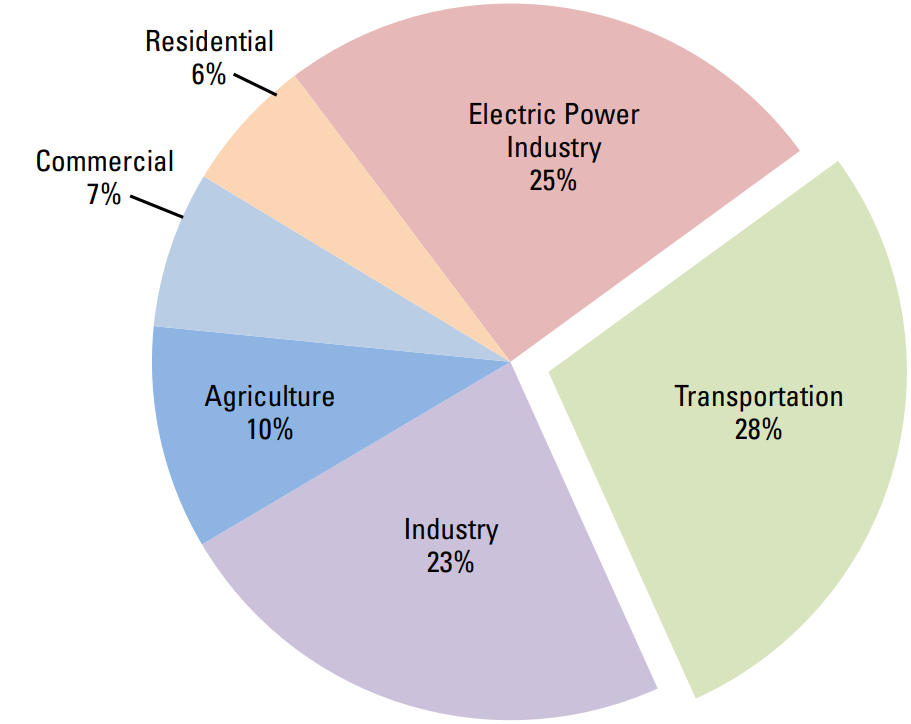

Direct greenhouse gas emissions by sector, 2022. (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency)

While transportation is vital to American prosperity, the transportation sector is the largest direct contributor of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions among all economic sectors. Even though passenger-car efficiency has steadily increased in recent years, the sector’s contribution to environmental degradation has continued to rise. Since 1995, U.S. transportation sector emissions have risen by almost 20 percent.

We cannot ignore the principal problems in the U.S. transportation system that lead to environmental degradation and economic inefficiency. Left untouched, they will hobble the U.S. economy for decades to come. These problems will also make it impossible to reach even the least ambitious carbon reduction and environmental protection goals.

The Sustainable Transportation Act is predicated upon the idea that restructured public investments can address these problems and reverse negative transportation trends.

The Problems with U.S. Transportation

What’s wrong with the U.S. transportation system? For one thing, transportation funding is insufficient and far too regressive, relying on fares and user fees that disproportionately burden poorer households. Also, we rely too heavily upon cars for short trips and lengthy commutes.

We have cultivated an environmentally costly infatuation with medium-duty trucks. Americans purchase far more heavy sport utility vehicles and pickup trucks than their “utility” or “pick-up” needs warrant.

Rail travel and transport is the solution to many of our transportation woes. The U.S. freight rail system is in some ways the envy of the world, but it could be readily improved and enlarged. Our passenger rail system, from streetcars to Amtrak intercontinental routes, needs major improvements in efficiency and reliability. Transforming these systems will require ambitious, publicly supported capital investment. This is crucial for bringing the U.S. economy back within its ecological limits.

Who wouldn’t want to ride the Amtrak California Zephyr? (Amtrak)

Unnecessarily long commutes, excessive air travel, and a growing population have also led to too much travel overall. Measures to limit suburban sprawl and air travel, alongside smarter approaches to population, can reduce U.S. travel. Better transportation finance and efficiency, for which the Sustainable Transportation Act is designed, can make the remaining travel more sustainable and accessible.

The User-Fee Death Spiral

U.S. transportation funding is stuck in first gear. It depends on direct user fees (fares) and indirect user fees (including fuel taxes that fund highway and transit maintenance). These financing methods are both insufficient and a source of confounding inequality.

Such direct and indirect user fees can be effective at discouraging improvident transportation choices when governments offer better options. However, they’re insufficient to cover minimal capital and operational needs, effectively short-changing transportation investment. This prevents the development of better options.

For equitable, well-functioning, and environmentally sound transportation, we need a more progressive and robust funding structure.

Coca-Cola Cowboys and Crippling Car Dependency

The largest single source of greenhouse gas emissions in the transportation sector is the light-duty truck, which includes SUVs, pickup trucks, and vans. As these vehicles rose in popularity in the 1990s and early 2000s, the average fuel efficiency of new U.S. vehicles actually declined. Passenger-vehicle efficiency has increased again since 2004, but the ongoing excessive use of light trucks has severely limited these gains. Due to their excessive weight and indirect emissions from fossil-fueled electricity, emerging electric-vehicle (EV) versions of these automobiles will do little to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

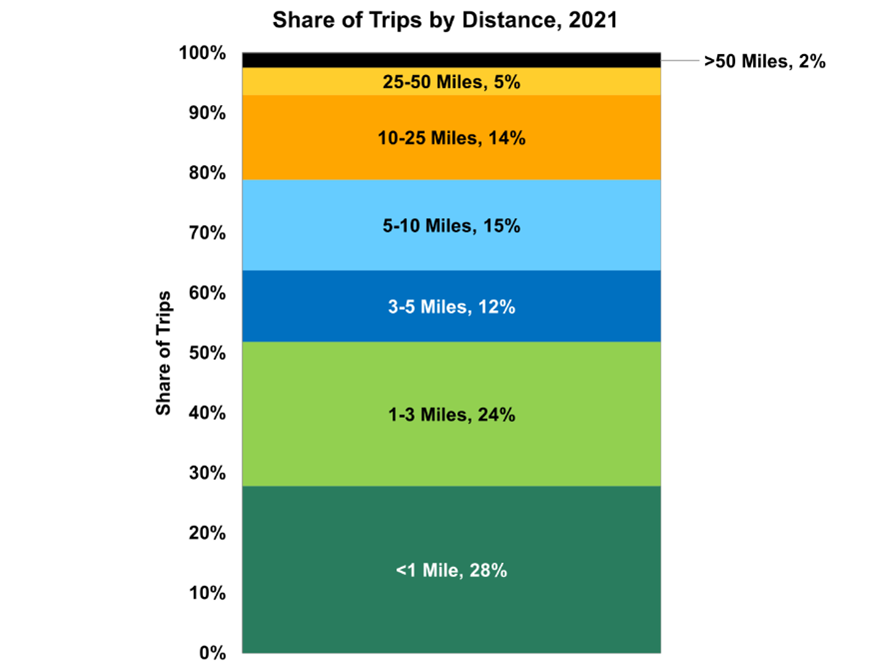

Over half of U.S. trips are less than 3 miles. (Bureau of Transportation Statistics)

Realistically, personal motor vehicle travel will remain an essential mode of U.S. transportation in many regions for decades to come. Half of all daily passenger-vehicle trips, however, are less than three miles. Such short trips, which came into vogue in the late 1990s, are ripe for conversion to rail, bicycle, or pedestrian transit.

This trend is making routine transportation more inefficient, environmentally costly, and unhealthy. For short-distance hour-plus commutes, delays are a consequence of inadequate metro light-rail systems. For hour-plus commutes over ten miles, the culprit is increasing automobile traffic.

To reverse the trend of short commutes taking more time, governments should subsidize intracity transit options. These range from simple streetcar systems to more complex metro-rail systems in medium and large U.S. cities.

EVs and Indirect Emissions

The U.S. transportation system doesn’t have much of an indirect carbon footprint, because it uses relatively little electricity. This indirect footprint accounts for less than one percent of the sector’s greenhouse gas emissions.

However, hybrid-electric and all-electric vehicles are gaining in popularity. Increased EV usage will decrease direct transportation emissions but markedly increase indirect emissions. This is because U.S. electric power is still so fossil-fuel dependent. Drawing on this power, EVs can do little to reduce overall greenhouse gas emissions. Residential and community EV chargers powered by renewable energy can help solve this problem.

Off the Roads and Onto the Rails

The U.S. freight rail system is the world’s most efficient. Yet, while the United States ships more goods by rail than Europe or Asia, we still ship too much freight by heavy truck. These trucks are responsible for the vast majority of ongoing highway maintenance costs, and their energy consumption is excessive.

Moving truck freight to rail would improve roadway efficiency for all users. Better integrating freight rail with other modes of shipping, expanding rail-system operations, and lessening freight rail’s carbon footprint should be national priorities.

Introducing the Sustainable Transportation Act

We need a bill to establish the principles and practices for sustainable transportation in the United States. This will be a feeder bill of the broader Steady State Economy Act. In particular, it will contribute to Section 10 of the SSEA, Housing and Transportation.

We can call this new feeder bill the “Sustainable Transportation Act,” as provided in Section 1. We’ll use the abbreviation “SUSTRAN” because we’ve used the acronym “STA” for the Sustainable Taxes Act.

Section 2 of the SUSTRAN Act comprises the findings and declarations of Congress. For example, in Section 2(a), Congress finds that “transportation systems that are inadequately subsidized and poorly financed promote an inefficient and unsustainable increase in per capita transportation consumption.” In Section 2(b), Congress declares (among other things) that it is the policy of the federal government to “encourage the establishment of multi-modal rail transportation networks that include street cars, higher-speed freight and passenger rail systems, and a modest number of high-speed passenger rail systems.”

Section 3 provides definitions. It identifies, for example, the “Commissioner” as the Commissioner of the U.S. Internal Revenue Service. It also helps clear up jargon such as “overhead catenary system” and “Class I railway.”

Sections 4 and 5 reformulate transportation-system financing away from regressive user fees that do little to encourage efficiency or environmental protection. They establish a more comprehensive reliance on federal general funds. CASSE’s Sustainable Taxes Act is a necessary companion to this sector-specific reform. Its tax reforms would make it possible to raise sufficient revenue for SUSTRAN Act investments. This would allow for the elimination of regressive transportation user fees, including those cited in Section 5, that serve no useful public purpose.

Section 4 imposes an excise tax based on passenger-vehicle curb weight. This is because vehicle curb weight will always correspond to energy use, dirty or “clean,” and has surprisingly little correspondence to real needs for larger passenger vehicles. This excise tax is designed to encourage people to select from the abundance of vehicles lighter than the 4,500-pound tax threshold.

The Hummer EV: still heavy, still big on greenhouse gas emissions. (Wikimedia Commons)

Section 5 repeals most of the existing transportation and vehicle excise taxes, such as those imposed on tire purchases. Like most transportation excise taxes, the tire tax does little to discourage undesirable behavior, like buying heavy vehicles. People will generally not choose a vehicle based on relative tire expenses, and tire purchases are unavoidable for car owners. As a result, such taxes do little for energy efficiency or environmental protection. Instead, they offer only an insufficient means of finance and represent a source of inequality.

Section 6 introduces a broad federal subsidy program to support critical capital improvements in the nation’s freight rail system. U.S. freight rail companies have a notable record of reinvesting in their systems. However, some investments that would align with the public interest are too risky for the companies to make, without ample government support.

The new subsidy programs in Section 6 include generous public assistance for the electrification of mostly diesel-powered freight lines. For freight rail companies, electrification is a desired capital project, but it carries an uncertain return on investment. Section 6 includes targeted assistance for overhead catenary systems and battery locomotives. It also includes assistance for placing new utility transmission lines along existing freight railroad corridors and connecting them to renewable energy.

Section 7 of the SUSTRAN Act introduces subsidies for the Amtrak intercity rail system. The system cannot improve if it continues to rely on meager and irregular fares and subsidies. With sufficient federal subsidies for construction and operations, Amtrak interstate travel would become an accessible and increasingly popular choice. This would move many cars off U.S. roads and many planes out of U.S. skies. The tangible result? More pleasant travel, more environmental sustainability, and enhanced efficiency.

Switzerland’s national rail system is known for being clean, well-coordinated, and scenic. (Unsplash, NDTV Travel)

Section 8 calls for the sunsetting of the Section 7 passenger rail subsidy program and for nationalizing Amtrak, to be known thereafter as the American National Railway Administration. This is a vital step for the measured expansion of U.S. passenger rail, upon which many of the other reforms in the Act depend.

Section 9 introduces subsidies for intracity light rail systems. With great capacity to reduce car traffic, intracity rail systems improve transportation accessibility and efficiency for all. Those who still drive passenger vehicles contend with far less traffic. Bicyclists and pedestrians are safer, too.

Section 9 establishes subsidies for simple streetcar lines, to encourage their fare-free provision and broad use, including by those with physical disabilities and limited mobility. It also includes access to bike-ped trailways. U.S. cities have long utilized simple streetcar systems, which remain popular and affordable wherever they exist.

New Orleans streetcars are as popular as ever. (Didier Moïse, Wikimedia Commons)

Section 10 introduces subsidies designed to address a key barrier to railroad efficiency: the prevailing track-sharing arrangements between freight and passenger systems that often stymie both. These subsidies would support investments in new switch infrastructure, track-curve straightening, new rail lines, and the construction of bridges and other infrastructure that allow for the removal of grade crossings. Especially in the Northeast, railroad companies have long targeted these projects as crucial to improved coordination of freight and passenger rail. Sharp curves, for example, limit speed and optimal timing for shared-track arrangements.

Sections 11 and 12 establish a new subsidy and modify an existing tax credit, to encourage sustainable community and home-based EV charging. The municipal subsidy would support the construction of fee-free EV charging stations powered by renewable energy.

Section 12 modifies the existing tax credit so that it is more likely to encourage genuinely sustainable EV charging. It limits the credit to the purchase of 120-Volt chargers and the associated installation of a renewable energy source. The modification intentionally excludes credits for Level II or Level III chargers, which are faster and provide more charge, but are more difficult to power with renewable energy.

Sections 13, 14, and 15 are predicated on the expansion of intercity (Amtrak) passenger rail travel, enabled by the subsidies in Section 7. Section 13 requires the Department of Transportation (in conjunction with the Federal Aviation Administration) to impose annual mileage limits on jet travel provided by airlines and administered by airport authorities. These limits are based on the previous year’s expansion of Amtrak passenger miles, by region. For flights under two hours, the Act requires a reduction in jet-travel passenger miles equivalent to 50 percent of the previous year’s expanded Amtrak passenger miles. For flights of two hours or longer, the Act requires a 40 percent reduction calculated in the same way.

Section 14 introduces caps on jet flight hours for non-commercial operators (individuals or businesses). These private operators account for only four percent of jet fuel consumption in the United States (and less than one-half of one percent of all transportation sector greenhouse gas emissions). Nonetheless, private jet travel is a necessity for few, if any, business travelers, and increased passenger-rail efficiency would render it even less necessary. The SUSTRAN Act places a modestly higher cap on flight time that third parties buy from jet owners.

These jet-travel caps would reduce flight hours in the aggregate, in five annual steps, to approximately fifteen percent below their 2020 level. Section 15 introduces penalties for any violation of the new mileage-based limits. (While the limitations on jet travel are not as aggressive as with Brian Czech’s futuristic Forgoing Flights for America the Beautiful Act, the first step is the most crucial.)

Why drive when you can do this? (John Luton, Flickr)

Section 16 rounds out provisions for the broad restructuring of U.S. transportation systems by establishing subsidies for the municipal construction of bicycle and pedestrian pathways. This includes subsidies for the acquisition of property needed for rights-of-way along proposed pathways. These subsidies are designed to minimize hurdles specifically for commuter pathways, for which design constraints are often complex.

Because the SUSTRAN Act would reduce but not eliminate transportation excise taxes, Section 17 mandates that remaining excise taxes be deposited in the government’s general fund. This also serves to encourage general-fund financing of the transportation system, supported by the implementation of the Sustainable Taxes Act. The few transportation excise taxes left intact or newly introduced are designed for dissuasion, not revenue.

Shifting funding mechanisms in this way increases both fairness and overall funds for public transportation. The national government is better suited than the private sector, which is driven by profit motives, to reduce the transportation system’s upward pressure on GDP and its ecological footprint. And we don’t have to choose between nationalization and quality. The world’s most highly rated transportation systems are in nations with officially or essentially nationalized rail networks.

What’s more, spending introduced in the SUSTRAN Act is largely compensated for by measures introduced in the Sustainable Budgets Act. These include savings from the elimination of overlapping or redundant agency-level services.

When U.S. passenger and freight rail systems first spanned the continent, they transformed the economy. Regressive public finance, automobile dependence, conspicuous consumption, and unsustainable population growth have marred the U.S. transportation system’s luster and utility. The SUSTRAN Act is designed to transform this system into a more sustainable and useful national asset. Transformed accordingly, the transportation system would broaden U.S. prosperity and serve as the backbone of a steady state economy.

David Shreve is a Senior Economist at CASSE.

David Shreve is a Senior Economist at CASSE.

At CASSE, we are on the right side of history with this one, even if we’re ahead of the pack in North America. See the growing outrage in Europe over the private jetting of this Belgian racecar driver:

https://www.thecooldown.com/green-business/max-verstappen-driver-private-jet-carbon-footprint/

Great quote: “I can’t believe they fly these monsters around the planet.”

The racecar driving itself is bad enough. In my opinion the greatest in-your-face affront to sustainability in North America is NASCAR, which I dove into for the Herald in 2022:

https://steadystate.org/driving-nascar-off-the-american-cultural-cliff/

Anyway, good job by Dave Shreve with the SUSTRANS Act!

A very short sighted and very weak assessment of what efficiency could be and obviously must be created. The technology exists for vehicles to be far more efficient than they are today. Fuel Vapiouisation could take 90% out overnight. Simply legislate for efficient engines…get rid of the gas gusslers. Down side of that the fuel companies lose their huge profit margins….the list goes on and on…Free energy through Tesla Science could run all EVs free.

In drafting these feeder bills for the Steady State Economy Act (https://steadystate.org/steady-state-economy-act-draft-table-of-contents/), we try to strike a balance between prohibitive policy and incentivizing policy. It’s true that this SUSTRANS Act is weighted more toward the latter. You are welcome and indeed encouraged to draft a segment for the SUSTRANS Act that prohibits certain types of engines. Make it good and we will definitely consider it. That’s one of the reasons we introduce these feeder bills online.

It should also be noted that while we expect continued advances in automobile fuel technology to render significant new fuel efficiency, and–as the article indicates–know that car and truck fuel efficiency has already been improved markedly in this way, our transportation “problem” has many factors. If we only have “greener” cars and trucks, we may still have clogged roadways and a poorly performing system. The technology you cite–existing and prospective–must be a small part of a bigger multi-modal transportation system.

This is all very exciting to me. Here’s another thought–though I haven’t yet bought one of these super fun-looking battery-powered bicycles, they seem to me like something that could really help in the “under 5-mile trip” category. However, this might not occur if these bikes would have to share the roadways with cars and trucks! What about the idea of creating bike paths along most exciting roadways, either just for the electric bikes, or for electric bikes plus traditional bikes?

sorry, I meant “existing” roadways, not exciting roadways! And ignore my second comment, as my original comment did go through after all.

David,

Indeed, one reason we chose the bike path-traffic jam image accompanying this article was to convey precisely our belief that well-planned bike-ped can work exceedingly well for these shortest of commutes. And though we didn’t have the space in which to elaborate, one of the reasons is because the new generation of E-bikes now make it much more practical for commuting on hilly terrain, where, otherwise, only the most fit bicycle commuters might brave the trail. As you’ve noted, we also understand that dedicated paths separated from automobile roadways are also a key part of this, which is why we included a federal subsidy and didn’t simply imagine that many local governments would be able to surmount the infrastructure challenges of such pathways on their own. Some are likely well-positioned to plunge in, but many are not, either because of lack of funds or complicated rights-of-way, intersection, or cloverleaf roadway barriers.