Keeping the County Great: Rappahannock’s Steady State

by Dave Rollo

Farms and forest occupy Rappahannock County. The Shenandoah Mountains lie to the west. (Wikimedia Commons)

It would be difficult to match the pastoral majesty of northwest Virginia, with its rolling hills covered in forests and prime farmland at the northern foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains. The region boasts the Shenandoah Valley to the west and Shenandoah National Park (SNP). Sitting at the eastern doorstep of the Park is Rappahannock County, part of the Piedmont region of the state, which lies between the mountains and the coastal plain.

Rappahannock is unique among the counties of the northern Piedmont for its careful approach to conservation. Unlike neighboring jurisdictions, Rappahannock County has carefully guarded its rural character and natural beauty—an astounding achievement given its proximity to the Washington, D.C. Metro (less than 50 miles away). Missing in Rappahannock are the big box stores, strip malls, fast food restaurants, and sprawl that are common outside the county’s borders.

Threats from Exurbia

“Super commuters” and telecommuters have created great demand for land in the counties west of Washington, D.C. Extending beyond the coastal plain cities of Washington, Arlington, and Alexandria, whose combined population is 5.5 million, the Piedmont region and the mountains beyond have felt the effects of this hunger for land.

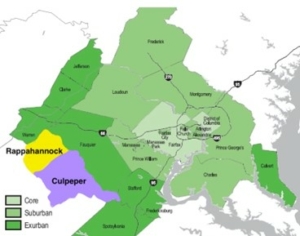

Rappahannock County lies on the periphery of the exurban D.C. metro area. (Wikimedia Commons, modified).

The population of suburban Loudon County has increased more than tenfold in 50 years, to 440,000 people. Fauquier County, sandwiched between Loudon and Rappahannock, has tripled since 1970, to 76,000 residents. Fauquier is now considered part of the 22-county D.C. metro area, out on the exurban fringe.

Yet despite growth pressures—actually, because of active resistance to them—the population of Rappahannock County has held nearly steady over the past half-century, at 7,500 people.

Growth pressures have intensified over the years and are now on Rappahannock County’s doorstep. The county has successfully staved off most conversion of land to housing tracts, but neighboring counties have approved large development projects within a few miles of the county line.

In Culpeper County, immediately southeast of Rappahannock, the County Planning Commission granted unanimous approval of a massive development at Clevenger’s Corner. The development consists of 774 homes and a 144,000 square-foot commercial center. The approval was consistent with the county’s “growth centers” vision described in its 2005 comprehensive plan. To the people of Rappahannock County, Clevenger’s Corner is an object lesson in the type of development to avoid. They point to it when they complain to their elected representatives about the consequences of loosening zoning restrictions.

Pressures of Growth Tested

Rappahannock residents’ preference for conservation was put to the test recently, as was Rappahannock County’s 2020 Comprehensive Plan, by two controversial development petitions in the villages of Sperryville and Washington. The proposal in Sperryville was denied, while the one in Washington was approved, but they both reflect a cautious review of development that is more or less consistent with a steady state economy.

Sperryville, with more than 350 residents, has a vibrant village center. At the boundary of Shenandoah National Park, it benefits from significant tourism, and is buoyed by visitors frequenting the handful of shops, galleries, and restaurants. It is unincorporated, and development decisions are made exclusively by the County Board of Supervisors.

In Washington, by contrast, commercial and cultural activity has waxed and waned over time, and population has fallen from a high of 250 residents to 86 today. The mayor has set a goal of increasing the town’s population to roughly its former high. Unlike Sperryville, Washington (and most towns and villages in the County) is incorporated; development within its boundaries falls under the purview of the Town Council.

The Sperryville development proposal was for changing the density requirement of a local parcel from five acres per home to two acres (referred to as “upzoning”). This proposal generated a great deal of public opposition. In response, environmental restrictions on the parcel were introduced, which reduced the developable area and the number of homes. However, a petition of nearly 400 signatures urged the Board of Supervisors to reject the rezoning request outright. Ultimately, the Board agreed with the opposition to the proposal and kept the current zoning, at five acres per home.

View of Main Street, Sperryville, Virginia (Wikimedia Commons)

Meanwhile in Washington, the Rush River Commons project consisted of a mixed-use (commercial/residential) proposal on 5.1 acres that featured slope constraints and environmental challenges. The Washington Town Council viewed the project as valuable for shoring up town commerce. They also liked its inclusion of space for nonprofits and 20 units of affordable housing, a key consideration in their comprehensive plan.

After approval of the first phase by the town council, the developer offered a second phase that not only entailed additional building but required expansion of the town boundary by three acres. This required approval from the County Board of Supervisors. County residents pushed back on the proposal, and it was only after the developer removed the residential component and met twenty-five other conditions that the Board approved the project.

Thus, although the Board of Supervisors finally approved the Washington development, it imposed a high degree of stringency in the review process. Concern over the town’s loss of 60 percent of its population was likely a key reason for the decisions by both the town and county governmental bodies.

In the Sperryville and Washington cases, meeting records, public comment, and letters to the editor of the local Rappahannock News illustrate a substantial degree of public input from throughout the county. Civic involvement explains, to a large degree, Rappahannock County’s success at preserving land and resisting growth pressures.

Comprehensively Speaking

The Rappahannock Comprehensive Plan of 2020 updated the previous 2004 plan in significant ways. The Board of Supervisors implemented a downzoning (an increase in minimum lot size) of approximately 90 percent of the county’s land. Current zoning allows only one housing unit per 25 acres. This check on development is popularly supported and was reflected in elected leadership and appointments to the Planning Commission.

The opening statement of the comprehensive plan emphasizes the value that residents find in the county’s undeveloped lands: “When asked what brings the most pride related to Rappahannock County, there were various answers generally related to the unique viewsheds, the rural nature, the preservation of land and open spaces, and the citizens that help keep it that way.”

Popular support for constraints on development is clearly evident: “When asked what should never change about Rappahannock County, responses generally referenced the natural beauty and the zoning restrictions that control development.” Clearly, residents prize the natural attributes of the county over proposed alterations imposed by development.

Fortunately, Rappahannock County can draw on state-level policy to limit land conversion. For example, a foundational element in Rappahannock’s success in farmland preservation is the State of Virginia’s 1971 LUVA (Land Use Value Assessment) law allowing local governments to assess land by its “use value” rather than its typically higher market value. Through LUVA, real estate taxes are lower for lands that are useful for production of food, fiber, or timber. This creates an incentive to keep land rural and productive. The policy is effective: Ninety-eight percent of farms in the county are still family-owned, and 80 percent are smaller than 179 acres.

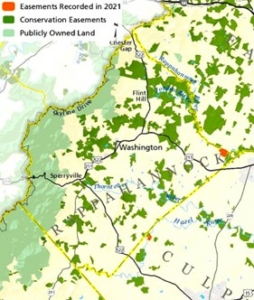

Rappahannock’s permanently protected land. (Piedmont Environmental Council)

The Piedmont Environmental Council, a regional environmental organization founded in 1972, has played a significant role in environmental protection and conservation for more than half a century. It promotes parks and trails, supports the local food system by connecting consumers to producers, encourages an active civic culture, and builds on land conservation successes.

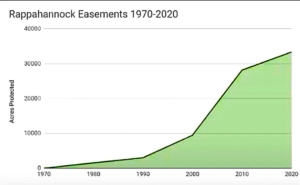

The PEC has permanently protected more than 420,000 acres through the use of conservation easements. In Rappahannock County, conservation easements total approximately 34,000 acres, 20 percent of the county’s area. These are held by a consortium of organizations, including The Land Trust of Virginia, Virginia Outdoors, local and state governments, and the PEC. Together with the Shenandoah National Park, conservation easements cover more than 38 percent of Rappahannock County.

The PEC goal is to place 50 percent of the privately held land in the Piedmont region—a million acres—into permanent conservation status. The PEC has determined that the 50 percent goal is the minimum area required to preserve species diversity in the region. The secondary goal is to create a vibrant rural economy.

The PEC is in the process of targeting farms in the upper Rappahannock watershed that could also provide an anchor for the rural economy. Farm Bill programs through ALE (Agricultural Land Easements) provide grants—up to 50 percent of the land’s fair market value—to farms for placing their land in easements, with tax benefits on the remaining land value.

The Need for Vigilance

The inclination of town and county residents alike is to resist sprawl, as reflected in the 2020 comprehensive plan. The Land Use section provides that ”…we the people of Rappahannock County declare it to be a ’scenic county‘ and all goals, principles, and policies will reflect and devolve from this fundamental recognition.” The “Principles” section includes six that are directed toward land conservation. Two principles pertain to economic growth and development. However, they call for maintaining “growth areas” of urban infill for commerce and affordable housing. Economic growth is allowed only when it “assists in maintaining our existing balance and is compatible” with the natural and rural nature of the county.

Principle 10 promotes the philosophy that “land is a finite resource and not a commodity” and needs protection. Principle 9 encourages “citizen involvement in the planning process,” citizen education regarding the value of the natural and rural environment, and provision of an avenue for citizen participation in the oversight of development proposals.

The Rappahannock Comprehensive Plan’s “Goals” section is likewise explicit regarding land conservation. Seven goals require protection and preservation of the natural attributes of the county. Only one goal entertains prospects for further economic growth. It includes the directive to “Define the future boundaries of growth in village and commercial areas necessary to preserve our community character and to maintain the balance that exists today.”

Since growth is constrained by restrictions and within discrete physical boundaries, what level of growth is likely, especially given the demographic and affordability challenges of the county? The Board of Supervisors recognizes that as the county ages, gentrification prevents younger and poorer community members from living and participating in the county. Yet younger residents are usually needed to work in agriculture.

The remarkable success of protection by conservation easement within the County. (Piedmont Environmental Council)

The comprehensive plan anticipates population growth of 0–1 percent per year. This is not a goal, but a response to a variety of causes. The plan indicates that infrastructure such as schools are adequate to accommodate an increase of 750–1,500 county residents. This means a total projected population of 8,800 people, similar to the County’s population in the year 1900.

Rappahannock’s comprehensive plan embodies a limits-to-growth ethic that is consistent with the county’s legacy of resisting development pressures. The use of conservation easements and support for an agrarian base with ecological integrity is also consistent with a steady state economy. However, conservation easements are vulnerable to violation, the doctrine of changed conditions, and other legal challenges in a nation pursuing economic growth. Vigilance will be required to maintain the terms of easements. Ideally, these easements would be bulwarked by a sturdy framework of conservation lands owned by the county or a fee-title land trust.

Continued advancement toward a steady state economy could also be encouraged by replacing references to quantitative “growth” in the comprehensive plan with principles of qualitative improvement. And because the county’s population growth has long fluctuated within a small range and at a low level, the county could explicitly aim to maintain this dynamic equilibrium for the purpose of protecting its biocapacity. With these moderate changes, the plan could serve as a model for keeping a county great by maintaining a steady state.

Dave Rollo is a Policy Specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

"Rappahannock County Courthouse" by taberandrew is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

"Rappahannock County Courthouse" by taberandrew is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

I am trying to relate this eye-opening article to my own context, in the Paris region, where we have areas that seem parallel to Rappahonnack County, especially with their high percentage of family farms. I love cycling through such places, and stopping at vibrant village centers like the one you described at Sperryville. Where I live, just north of Paris, we are experiencing planned densification. I like the density, because it makes everything walkable, but it seems excessive. I made this critique to our councilman in charge, with our mayor at his side. His response was that the orders are for densifying here, in order to protect the equivalent of our Rappahonnacks.from population pressures, and to reduce commute distances as well. I am simply reporting what was told to me, wondering if it makes sense. Does the idyllic nature of Rappahonnack County depend on increasing density in other areas?.