Technocene Ground Zero: Counties Face Off with Data Centers

by Amelia Jaycen

Data centers hold from a few hundred to more than a million servers used for processing huge amounts of data created by average citizens participating in the modern world. (Victor Grigas, Wikimedia Commons)

In counties across the U.S.—rural and urban, democrat and republican—communities are living up close and personal with data centers. And the new neighbor is a real nightmare.

The number of data centers in the U.S., whether planned, under construction, or operating, is 3,897. This is by far the most anywhere in the world, and the number is increasing weekly.

We are hitting our heads on the ceiling of limits to growth. We have now generated so much data—projected to reach 349 zettabytes globally in the next three years—that processing it, storing it, and even its disposal are so resource intensive, communities have to compete with data centers for water and electricity. They are forced to trade their dark skies and coveted beauty for noisy data centers and ramped-up power plant pollution. We risk entering a “Technocene” era, in which data is the most dominant force impacting planet Earth. We could spend the rest of our lives—and precious natural resources—managing it.

Drowning in Data

Anyone participating in modern society creates and consumes a staggering amount of data, and the numbers are increasing at breakneck speed.

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego, estimate Americans consumed 3.6 zettabytes of data in 2008, and the number continues to balloon rapidly. A zettabyte is 1 with 21 zeros at the end, one billion trillion bytes.

Growth in data consumption—and data centers—is often pinned on AI, which requires high-intensity processing power. But it’s not just AI. Numbers vary, but there are approximately 19 billion internet of things (IoT) devices connected to networks across the spectrum of modern life. The number of IoT devices is projected to reach 40 to 125 billion in the next five years.

Two employees in a “hot aisle.” Data centers are designed with alternating hot and cold aisles, but energy-intensive AI makes it difficult to keep servers cool. (Robert Scoble, Wikimedia Commons)

We create, consume, and store quintillions of bytes of data through video streaming, social media, online shopping, digital banking, and home security cameras. Weather monitoring, warehouse automation, hospitals, and transportation systems also require immense amounts of data. Every business and personal encounter in modern life, from emails to paying bills, from travel to personal fitness, involves data.

The average American consumes 34 gigabytes of data a day. Meanwhile, global investment in AI is expected to surpass $337 billion this year. The amount of data will continue to rise as AI accelerates along with the mountains of data created by individuals, corporations, and governments.

More Data, More Data Centers

Processing all this data uses a lot of electricity. Data centers are using more than four percent of all electricity in the United States. In the next three years, that number is expected to reach twelve percent. If that trend continues, in less than ten years, data centers will account for almost 30 percent of all energy used in the United States.

Megacorporations are building hyperscale data centers housing more than a million servers. These ultra-powerful distributed computing clusters combine processing power from different data centers. The biggest industry players are in a race to set up infrastructure to enable artificial general intelligence, or AGI, with intelligence equaling or surpassing humans. Projects like Microsoft’s Stargate and Amazon’s Anthropic are the biggest yet, as noted in a TIME article: “Computational infrastructure of this scale has never been seen before in human history.”

How will we keep up with the demand? Across the United States, there is a multi-year queue to connect to the grid for both data centers and solar and wind-power installations. But the U.S. power grid is in desperate need of upgrades, and it might be the only grid in the world without a feasible modernization plan. Data centers are driving demand beyond what the grid can handle, and fast development threatens to throw efforts to decarbonize power generation out the window.

Power grid updates are expensive, and the costs are being handed to taxpayers on their electric bills. People in counties with power-hungry data centers, facing falling property values, noise, and pollution, are tired of shouldering the bill. In a video interview with Bloomberg, an activist in northern Virginia notes, “Now is the time… to hold the wealthiest corporations in the world accountable for the energy they need for their business model.”

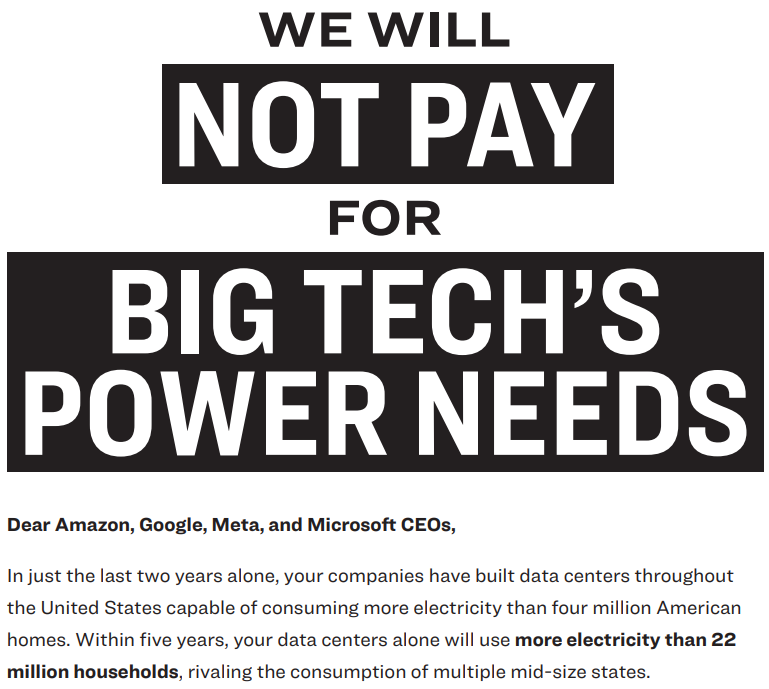

On Sunday, June 29, 2025, Sierra Club published a full-page letter in the San Francisco Chronicle and Seattle Times demanding Big Tech pay for its own power needs and stick to its clean energy commitments. (Sierra Club)

On June 29, Sierra Club published an open letter demanding big tech pay for its power needs and work with utilities to power data centers with renewables: “Within five years, your data centers alone will use more electricity than 22 million households, rivaling the consumption of multiple mid-size states.”

Data centers draw huge amounts of electricity and water to keep equipment cool. Megacorporations, such as Google and Apple, can afford hyperscale facilities with state-of-the-art equipment for increased efficiency. However, they process higher volumes of data and, as a result, use more natural resources on the whole (a case of Jevons Paradox). Meanwhile, some smaller companies attempt to retrofit existing buildings not designed for the purpose, and struggle with efficiency in the battle to keep servers cool.

According to Gary Wockner, a scientist and water-protection activist in Colorado, “Data centers thrive where water is cheap, electricity is cheap, and regulations are minimal. So, you see them popping up in places that have one or more of those characteristics, and it’s an increasing problem across the U.S.” In an interview with the Steady State Herald, Wockner highlighted concerns with data center water use. “This includes in the Colorado River basin, in Nevada and Arizona, the two most arid states in the nation, where water prices are often federally subsidized. The water has been subsidized by the federal taxpayer, subsidized by the complete damming and destruction of the Colorado River.”

Carbonivores Consume

The energy demands from thousands of data centers have tripled the electricity load on U.S. grids. Demand is on track to double or triple again in the next three years, according to a 2024 Department of Energy (DOE) study. Straining water supplies across the western United States, and now amped up by AI power demands, data centers have become hyper-consumers pressing the upper limits of energy and water use. It’s not a stretch to call data centers “carbonivores”, as data center anthropologist Steven Gonzalez Monserrate notes.

How much energy data centers use—and whether it’s clean or fossil fuel-based—is being radically underestimated and couched in “creative accounting”. Some researchers say policies will play a big role in determining the ecological impact of data centers. They suggest putting in place efficiency standards and benchmarks for data centers, investing in new technologies to reduce the industry’s reliance on fossil fuels, and developing open-data repositories for data center energy use. However, as it stands, data companies across the board are not sharing information about power use and efficiency.

There has also been a push for more transparency about the energy demands of AI. Different AI models vary in energy use, depending on the specifics of the software design. Energy use can vary by as much as 50 percent between companies and models. Using an advanced AI model for a basic question produces more CO2 than a simpler model. Several organizations have created indexes, such as the AI Energy Score leaderboard and the LLM (large language model) Leaderboard performance index, to help people choose which model to use.

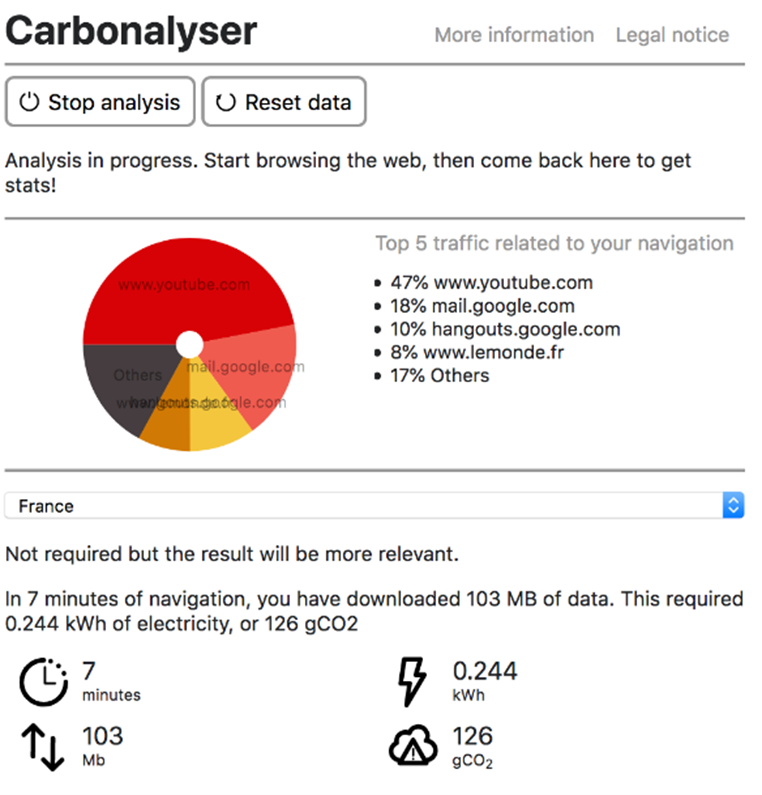

How much data do you use as you surf the web? (The Shift Project, Carbonalyser)

There are also tools to help internet users understand their actual impacts on the physical world. For example, the Firefox browser extension Carbonalyser measures the amount of data moving through your internet browser as you work. It calculates the energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions resulting from what you do online. As noted on the Carbonalyser page: “Visualizing it will get you to understand that impacts of digital technologies on climate change and natural resources are not virtual, although they are hidden behind our screens.”

On the other side of that one-way screen, data center companies are working to shuffle billions of bytes to your fingertips, and you are invisible to them, too. Their focus on providing speed and failproof access to data makes them blind to human health and happiness in the communities where they build and operate.

To understand the real-world impacts of our data use, the best place to look is the rapidly unfolding ground zero: in counties across the United States where citizens are battling with data center developers. Residents say development decisions don’t seem to factor in human beings. It’s all about the bottom line.

Coming Soon to a County Near You

Across the country, technology companies are boastfully announcing plans to build the biggest data center. Meanwhile, residents stand dumbfounded at the secrecy, poor choices of locations, lack of safety, increase in noise, and size of the large buildings. The imposing infrastructure often expands over the course of several years to include a cluster of data centers in giant complexes squeezed among residents.

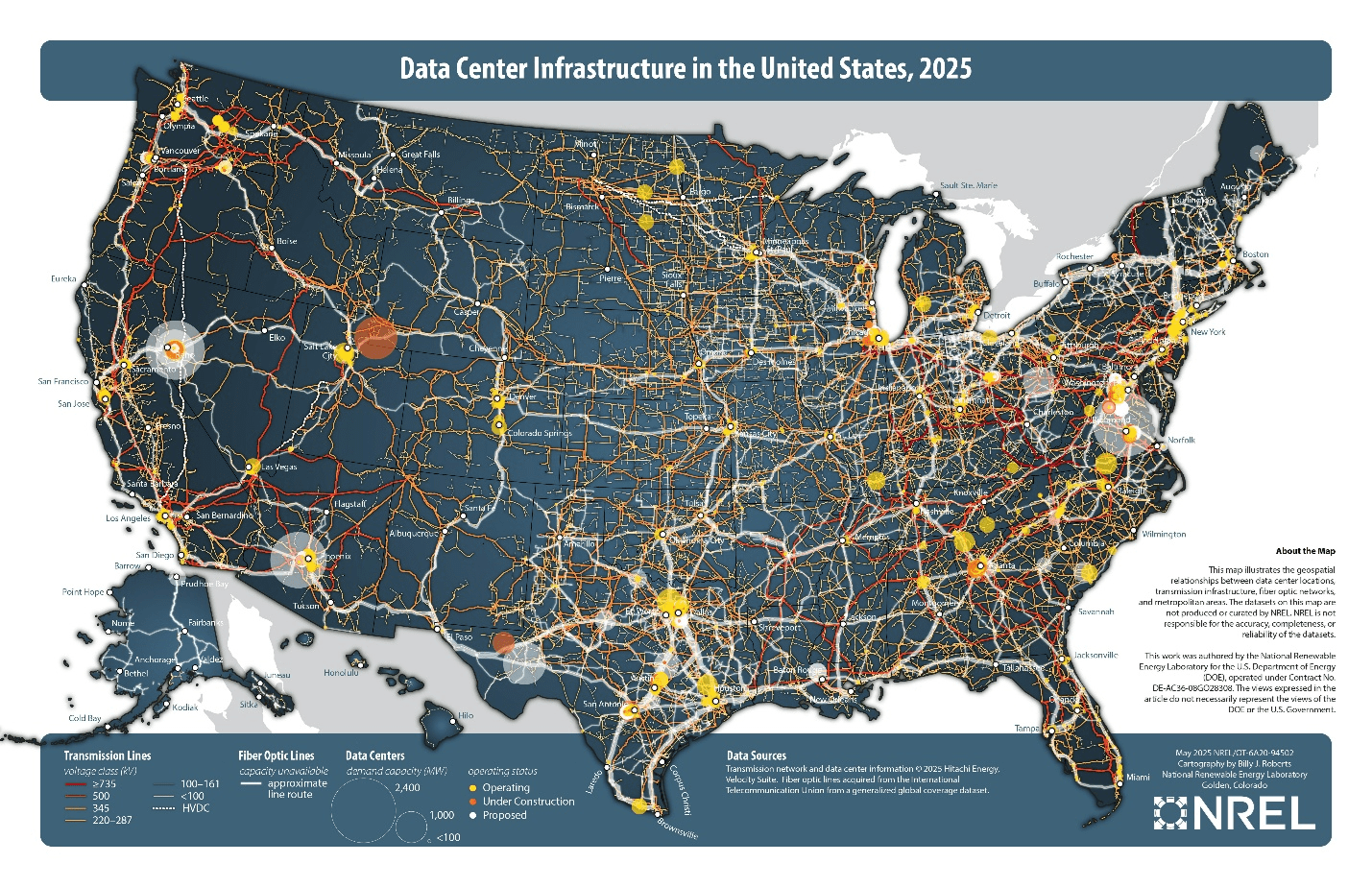

A map of data center infrastructure shows relationships between transmission lines, fiber optic lines, data centers, and major metropolitan areas. The map’s creator said it is “a telling viewpoint of the growth of the sector.” (National Renewable Energy Laboratory | View Map)

Willams County, North Dakota, can’t sleep because of 70-decibel noise 800 feet from front residents’ front doors. In northern Virginia, just outside Washington, D.C., data center development has been the most intense anywhere on the globe. Residents suffer from out-of-control development. They worry about the hundreds of transmission projects needed in the next few years to supply ever more data centers.

In Oregon, Meta has a 10-data-center complex outside the small town of Prineville, which suffers from drought. Residents can’t square the economic benefits with the environmental drain. As the Central Oregon Informed Angler reported: “The bottom line is that data centers have provided economic benefits to Prineville, but they continue to be a drain on our environment.”

Across the west, in Colorado, Arizona, Nevada, California, Utah, Idaho, and Washington, high-intensity water withdrawals for data centers are draining local resources. In 2021, Google used 355 million gallons of water in The Dalles, Oregon. That represents a quarter of the city’s water, and its water use has increased every year.

In April, the DOE issued a request for information to get input on whether and how AI infrastructure could be built on DOE lands near national labs. These labs include Pacific Northwest Laboratory, Argonne National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, and Los Alamos. While touring one of the sites in April, the secretary of energy compared the AI race to the Manhattan Project to build the atomic bomb.

Texas, the only state with its own electric grid, is scrambling to supply massive amounts of energy for the $500-billion Stargate AI project. Many worry about the health impacts of the ramp-up. Meanwhile, in Granbury, Texas, which is home to a data center devoted to Bitcoin mining, residents are suffering from a variety of strange, debilitating illnesses. These include racing heartbeats, drainage from the ears, and waking up vomiting from the constant hum of the data center’s noisy operations.

Two Roads Diverge

With such brazen disregard for human health, it’s easy to feel we are slipping into the Technocene. Those living out the nightmare—and any one of us could be next—are sounding alarm bells on an industry with no accountability, no standards, no regulations, and no rules.

Michael D.B. Harvey uses the term Technocene in his latest book, The Age of Humachines: Big Tech and the Battle for Humanity’s Future. Harvey lays out how a focus on the bottom line and a commitment to technology with zero consideration of the effects on human beings could lead to a very bleak future. He highlights “the desperate extremes of global disruption that will occur if capitalism continues down what the UN General Secretary calls our current ‘highway to climate hell,’ amid the possible collapse of multiple Earth systems.”

But Harvey presents an alternative, too: the Ecocene, in which we cease growth for growth’s sake.

“The Ecocene recognizes the extraordinary gifts that fossil fuel and human technology and science have conferred on us, but cautions that we now need the self-discipline to say ‘enough is enough.’ Instead of smashing planetary limits in pursuit of profit, a new integrated, life-based science will seek harmony with nature. Rather than jeopardizing the essentials of humanity, the core skills and talents of being human will be built on and enhanced with the dignity of all respected.”

Michael D.B. Harvey suggests there are two paths before us: the Technocene, in which technology development robs us of our humanity, and the Ecocene, in which the greatest parts of being human on Earth are preserved by pumping the brakes on runaway technology development. (Albert Bridge, Wikimedia Commons)

We are seeing the real impacts of runaway growth that values dollars and technologies over clean air and kids. All of us are suffering indiscriminately in counties across the United States, regardless of age, race, or politics. It would be wise to change course, so if we ever decide we want to do something besides deal with our data nonstop, there’s a real world left to visit.

“The Big Tech juggernaut is not unstoppable,” Harvey says. “We can set in motion another kind of revolution, one that is ecological and democratic and can achieve planetary sustainability while increasing real freedom, equality, and life satisfaction.”

Amelia Jaycen is a program manager at CASSE.

Amelia Jaycen is a program manager at CASSE.

A very, very timely article. I’ve been watching the growth in estimated electricity consumption for data centers and thinking “this cannot go on.”

I’ll just add (since I work in tech, for better or worse) that the counties and regions that think data centers bring jobs should revisit that belief. Essentially, as the hardware parts are increasingly standardized and commoditized, it becomes easier and more attractive to have robots do a lot of the installation and swapping out of failed components. Data centers racks and components are designed to be easy to work with, no tools required.

I saw a demo of a data center robot, sort of a miniature and more agile fork lift, and it was quite capable. On top of that, a great deal of networking work that used to involve human hands moving cables around is now done remotely via configuration changes to a “networking switch fabric.”

I would urge county planners to think skeptically about projections of jobs coming to their rural or other counties. Other than a couple security guards at the entrance (paid minimum wage), there are no humans required in this future.

Data centers should be required to provide the bulk of their power on site.

The average human being – drowning in data; devoid of knowledge.

Thanks Amelia for this outstanding article on the data centre threats of the Technocene.

The piece is full of some very scary revelations, such as “In 2021, Google used 355 million gallons of water in The Dalles, Oregon. That represents a quarter of the city’s water, and its water use has increased every year.”

Very few people either side of the Atlantic are cottoning on to what the AI and IoT revolution really involves environmentally, and that’s before we start reckoning with the impact of the one billion plus robots forecast for the next 10 years.

Also I love the pic, illustrating the choice between the Technocene and the Ecocene – the high road or the low road indeed!

Michael DB Harvey

London, UK

Interesting article thanks. It confirms my hypothesis that the “need” for AI has less to do with new innovation than just to keep up with ever increasing data. I mean, the wealth of information (whether it is useful or not is a totally different question) has just increased so much that we need AI just to manage and “make sense” of all that data. I wrote a bit more about that here: https://gardenearth.substack.com/p/the-ear-tags-of-our-cows-spell-the