The Economic Priority of the Seven Wealthiest Countries: More Wealth

by Alix Underwood

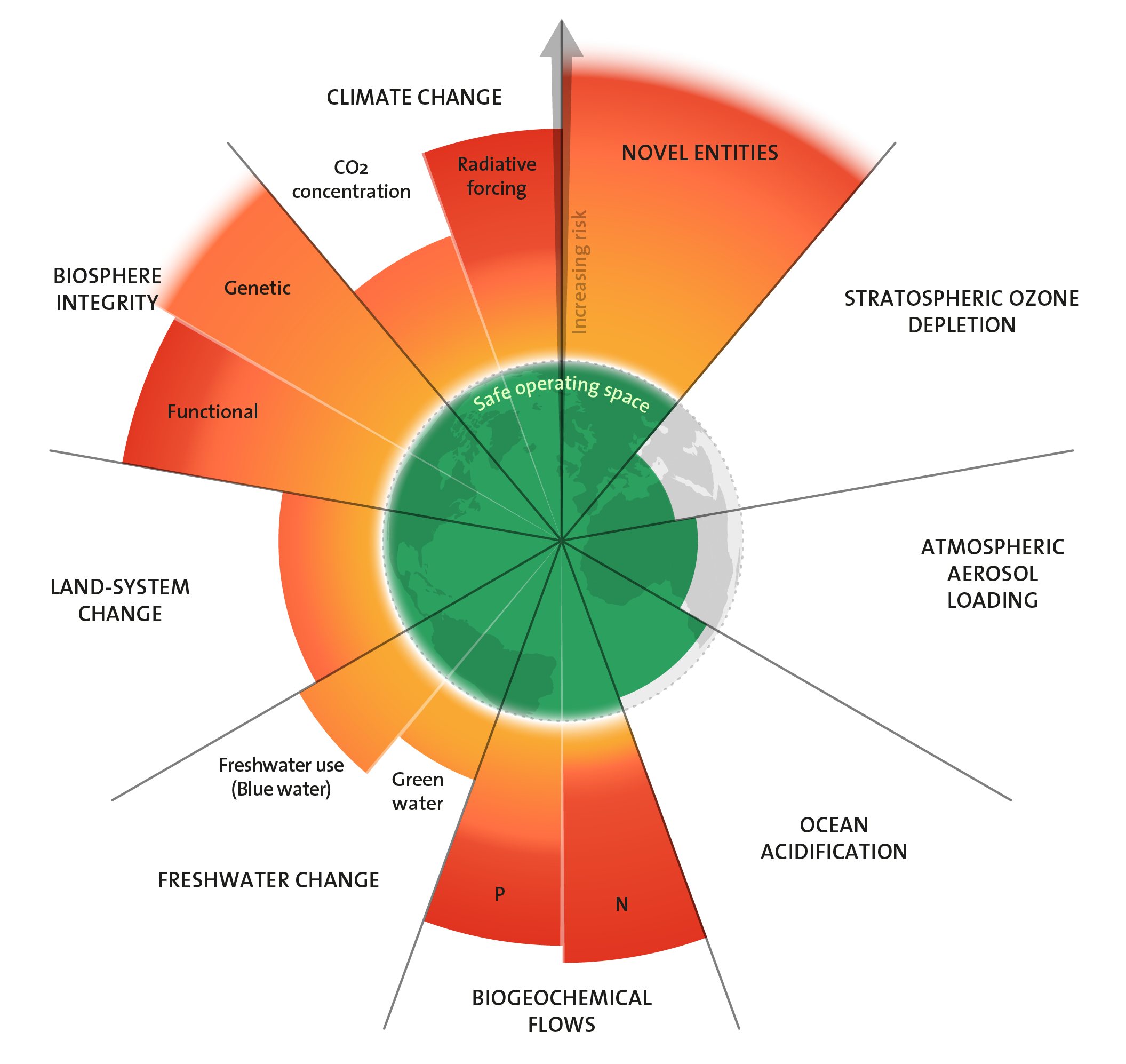

Climate change isn’t the only symptom of humanity’s overshoot of Earth’s carrying capacity (Azote for Stockholm Resilience Centre, based on analysis in Richardson et al 2023).

Almost half of humanity lives below $6.85 per day. This population does not consume goods and services at a rate exceeding Earth’s capacity. Yet here we sit, on the wrong side of six of the nine planetary boundaries identified by the Stockholm Resilience Centre.

How did we get here? Via the economic activity of the other half of humanity. The planet, and all its inhabitants, desperately need this population to slow down. We need the over-consumers to take a deep breath of the fresh air that remains and realize that they lose more than they gain by consuming more. In other words, we need steady statesmanship.

This overconsuming population, of which I am (and probably you are) a member, does not fall neatly into some national borders while the other half of humanity falls into others. However, there exist immense international economic inequalities. And given the toothless nature of global governance institutions, national governments often set the stage for economic priorities. Their mandates and funding trickle down to local governments.

So, starting with the very wealthiest of countries, what are national governments’ economic goals, priorities, and strategies? Are any of them striving for true sustainability: a controlled, equitable slowdown in production and consumption and, ultimately, a steady state economy? Using GDP per capita, in purchasing power parity (PPP) of constant 2021 international dollars, I determined the seven wealthiest countries. I excluded countries with populations below five million. I then explored government agency websites and publicly available long-term economic and development plans.

Spoiler alert: it didn’t take much digging to find “economic growth” listed as a goal, often the central goal of agencies focused on economic affairs. However, there is some tonal and contextual nuance in the ways that governments call for economic growth.

Let’s take a look at the seven wealthiest countries, including information about poverty, unemployment, and extreme wealth within their borders. Unless otherwise linked, statistics come from the World Development Indicators.

7. Denmark

Denmark is the seventh wealthiest country, with a GDP per capita of $72,034. It is the only country on this list with an unemployment rate surpassing five percent. This is reflected in the government’s fiscal policy and resilience plans, which focus heavily on employment. Economic growth is often considered the primary, or the only, avenue to increase employment. However, the global, historical relationship between GDP per capita and employment is shaky.

Regardless, economic growth is not presented in Denmark’s policy documents as a means to the end of higher employment. It is presented as an end in itself. The government aims to “strengthen the foundation for growth and employment” (italics added). It promotes a digital transition to “strengthen welfare, equality, growth, employment and the green transition.” Growth is a standalone goal.

The Ministry of Industry, Business, and Financial Affairs works to ensure “that the Danish business community continues to generate substantial growth.” Humanity would require over 4.5 Earths if everyone lived like a Dane. Therefore, a goal to increase the production and consumption of goods and services (economic growth) is highly inappropriate for Denmark. There are more sustainable ways to increase employment, such as reducing working hours and establishing income ceilings.

6. United States of America

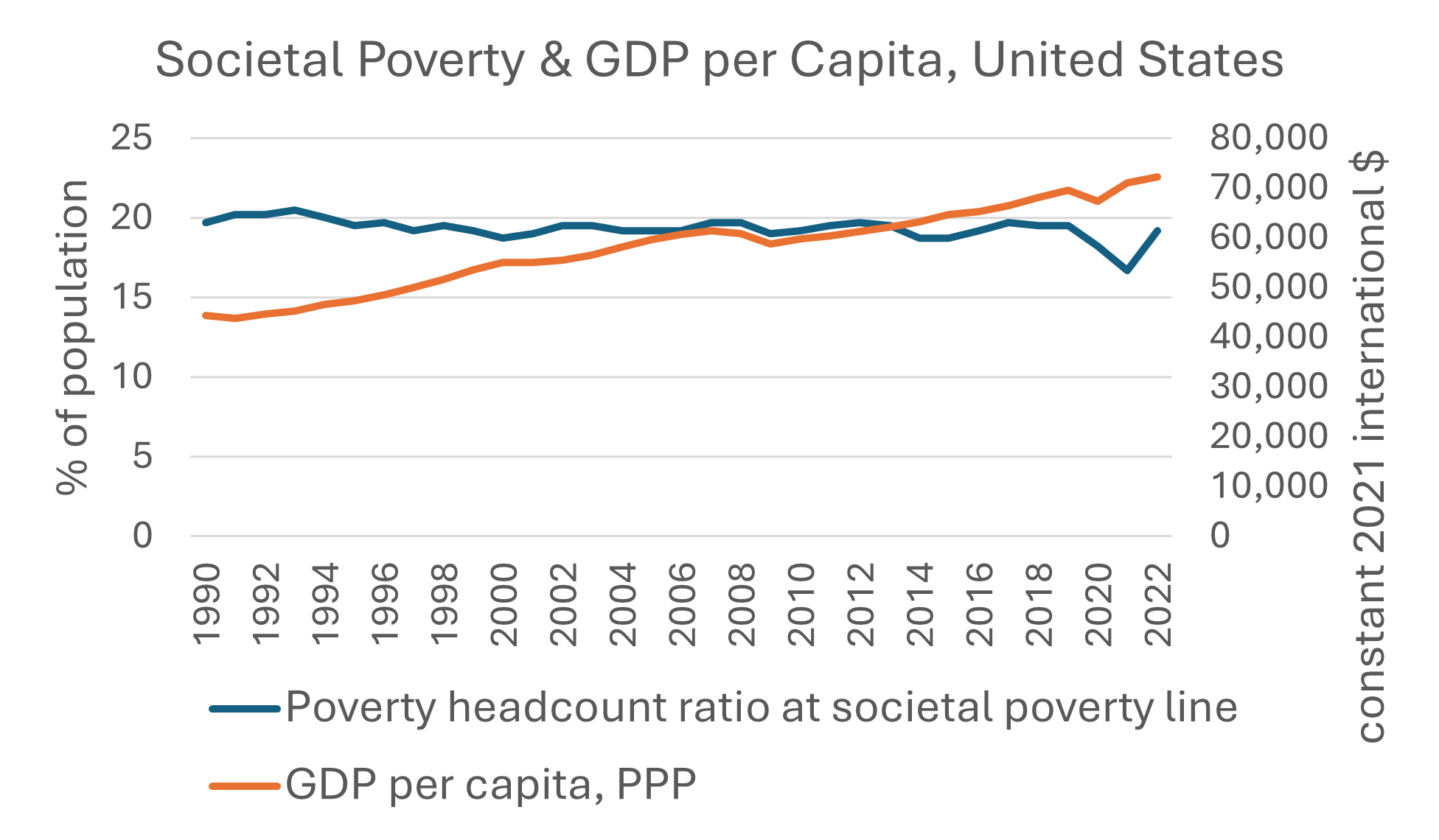

The United States’s GDP per capita is $73,637, and its unemployment rate is 3.6 percent. By the $6.85 per day standard, the U.S. poverty rate has been two percent or lower for decades. However, around 19 percent of the population lives at or below the “societal poverty line.” This relative poverty metric is essentially $2.15 per day (the international poverty line) plus 50 percent of the country’s median income. Societal poverty rate does not appear strongly linked to GDP per capita. The latter has risen steadily over the last three decades while the former has fluctuated around 19 percent.

GDP per capita has increased fairly steadily. Meanwhile, the percent of the U.S. population below the societal poverty line has fluctuated around 19 percent (author’s graph, data from World Development Indicators).

Nonetheless, the U.S. government remains committed to economic growth at all costs. The Department of the Treasury, the Department of Commerce, and the Economic Development Administration include economic growth in their mission statements. Even the Environmental Protection Agency’s mission mentions the importance of economic growth.

The U.S. lifestyle, if everyone had it, would require almost five Earths. The United States is home to almost 150,000 ultra-high net worth (over $30 million) individuals, more than any other country. With some tax reform, the United States has plenty of wealth to guarantee a minimum income. After all, the ultra-high net worth (UHNW) population’s $17 trillion in cumulative wealth is enough to send a check for $260,000 to every U.S. resident in poverty.

5. United Arab Emirates

The UAE has a GDP per capita of $75,627. It has the lowest unemployment rate of the countries on this list, with over 97% of its labor force employed. The UAE has all but eradicated poverty by international standards. The country has also created favorable conditions for its UHNW population. Though it hasn’t made the top ten in this department, the World Ultra Wealth Report 2023 assures us that the UAE is experiencing strong UHNW growth. This population likely holds much of the responsibility for the UAE’s immense ecological footprint. We would need 5.6 Earths for everyone to live like an Emirati!

According to the country’s leadership, it’s not enough. We the UAE 2031 is the president’s vision for the future. One of the key national indicators of the vision, launched in 2022, is to double the country’s GDP, from AED 1.49 trillion to AED 3 trillion. For context, the UAE’s population is expected to grow by only fifteen percent from 2023 to 2030. In other words, a doubling of the economy is entirely unnecessary.

4. Switzerland

St. Moritz, a Swiss ski resort town that has hosted two Winter Olympics, is a popular upper class destination (Dennis G. Jarvis, Wikimedia Commons).

Switzerland’s GDP per capita is $82,914. In 2022, the country was home to 110 billionaires with a collective net worth of $338 billion. This relatively large share of the population (1 in 80,000 people) is attracted to Switzerland by low taxation. Perhaps the country can afford for Switzerland’s State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) to modify the first goal listed on its website: “…to contribute to sustained economic growth…”

I did find an official Swiss document—a country report, which SECO was not involved in writing—calling for “environmentally sound economic development within planetary boundaries.” “Development” is an ambiguous word often used synonymously with “growth.” However, it is a step in the right direction, especially when used alongside “planetary boundaries.”

Switzerland has an umbrella organization, economiesuisse, that advocates for the interests of around 100,000 Swiss companies. This organization feels the need to take a defensive posture on their Economic Cycle and Growth webpage: “…economic growth is often demonized and associated with an increasing use of resources.” They ensure their members that “economiesuisse regularly takes a stand on the growth debate…” This acknowledgment of a “growth debate” signals a society awakening from a decades-long growth trance.

3. Norway

Norway has the third-highest GDP per capita, at $90,501. The government’s long-term economic strategy, which emphasizes the renewables transition, is less growth-at-all-costs than many others covered here. The document’s authors even acknowledge that “all power production has environmental consequences” and “the need for increased renewable power production may conflict with the preservation of critical natural values or alternative land uses.” Rather than a reduction in production/consumption, efficiency is lauded as the solution to resource limitations.

Ultimately, Norway’s strategic plan is the same as the others in that it explicitly calls for economic growth. It says this growth must be “achieved within a framework that…reduces greenhouse gas emissions, pollution, and loss of nature.” The world has yet to see such a framework, because it is a fairytale unmoored from the basic principles of ecology and ecological economics.

As in the rest of the world, COVID-19 took its toll on Norway’s vulnerable populations. In 2020, 12.6 percent of the population was at or below the national poverty line (which is 18 times higher than the international poverty line). The economic distress experienced by these Norwegians is an issue of distribution, not quantity. This is evident when one considers that Norway’s capital, Oslo, is projected to have the fastest-growing UHNW population of any city on Earth.

2. Ireland

Ireland is one of two countries on this list with a GDP per capita surpassing $100,000, at $115,625. Similarly to Norway, Ireland’s government websites and planning documents don’t exude an “economic growth for the sake of growth is the ultimate goal” message. Project Ireland 2040, the government’s long-term overarching strategy, repeatedly discusses the need for growth. However, growth is almost always couched in the context of the estimated one million additional residents that the country must accommodate from 2016-2040.

Almost one-third of the way through that timeframe, Ireland’s population stood just over five million in 2023, well on its way to the projected 20 percent increase. This high population growth rate, largely driven by immigration, sets Ireland apart from other members of the European Union. The country will indeed need to bolster its job market and develop some new infrastructure to support its new residents.

However, if we take Ireland’s 2023 real GDP (PPP, international dollars) and divide it by the projected population of just over six million, the result is a GDP per capita of almost $97,000. With some creativity and wealth redirection, Ireland does not need to grow its economy to support its influx of migrants.

1. Singapore

The richest country with a population over five million, Singapore has a GDP per capita of $127,544 and an unemployment rate of less than 3.5 percent. The Ministry of Trade and Industry’s vision, laid out in Singapore Economy 2030, is explicitly, unabashedly all about growth. The very purpose of the vision is to guide the country to “chart the next lap of growth.” The landing page for Singapore Economy 2030 contains a little over 200 words of text, and it contains “grow” or “growth” five times and is sprinkled with other growth-related words, such as “widen,” “expand,” “build,” and “increase.”

Gan Kim Yong is Singapore’s Minister for Trade and Industry. He sets the economic stage for the world’s wealthiest country (Titlutin, Wikimedia Commons).

Unlike Ireland, Singapore’s population is only expected to grow by a few hundred thousand by 2050. So, who is this economic growth for? The thriving and insatiable population of Singaporean billionaires? Home to 54 billionaires in 2022, Singapore ranks thirteenth as a country and eighth as a city in billionaire population size. Amongst these top-ranked cities, Singapore had the highest annual increase in billionaire numbers. This country does not need to—and, from an environmental justice perspective, has no right to—continue to grow its economy.

How to Shift the Narrative

The priorities and strategic plans written into existence by government personnel may seem out of reach. However, to the extent that democracy still has a foothold, they reflect public priorities, stemming from the issues affecting voters and the solutions they perceive as effective.

Your lifestyle speaks volumes about your priorities. However, you could take your steady statesmanship a step further by contacting your representatives (it can actually make a difference) about limits to growth. And of course, as the United States witnessed last week, your vote is the ultimate expression of your political values.

Some local politicians have taken stances against the growth machine. However, federal political candidates who advocate for a steady state economy are yet rare. Nonetheless, as we have seen, even some pro-growth governments acknowledge planetary boundaries. There is nuance in how much they are willing to sacrifice for growth.

The president-elect of the United States, the world’s second-biggest greenhouse gas emitter, has promised that his administration will pull out all the stops for growth. Trump’s win could mean an additional four billion tonnes of emissions of carbon dioxide equivalent by 2030.

Alix Underwood is a Research Associate at CASSE.

The recent United States election was all about higher personal purchasing power for less-educated Americans, full stop. The only ways to placate them that I know of would be (1) more quantitative easing (printing money) or the equivalent, (2) more deregulation, (3) reducing the population, (4) war of conquest, or (5) economic restructuring to allow a lower energy & materials throughput economy. Under the new administration, #’s 1-3 are all likely. #5 is extremely unlikely and #4 is unknown likelihood. #1-3 increase the risk of a 2008 style economic meltdown, and decrease the toolkit for mitigating it. Let’s hope that the economic meltdown comes during the watch of the administration that precipitates it, rather than on some hapless future administration inheriting its legacy. Economic corrections are never pretty. People suffer. Suicides increase. But sometimes there is no way out of one.

Good insights, I think I broadly agree.

Years ago someone observed that humanity would move to a steady state economy at some point, it was just a question of whether this move would be voluntary and somewhat orchestrated, or if it would be involuntary and basically picking up the pieces after a colossal failure of the current growth model. I take no pleasure at all in saying this, but it is looking more and more like it may be the latter. Sigh :(

Dear,

What can I say?

As long as we have interest-banking where P – P + In results in a Ponzi scheme of insoluble debt

As long as we have a stock market where C + P = C’ + P = C” ad infinitum…

My proposal is to criminalise these compounding monstrosities altogether, because frankly, this is not going well…

Be careful Alix. Ever asked yourself how a person can live on $2.15 per day, which is considered the International Poverty Line (upgraded from $1.90 per day)? They can’t, and they don’t. These figures are based on the monetary value of goods and services produced within the formal economy. Ignored are the public goods that can be freely accessed plus the goods and services that the very poor largely survive on that are produced within the informal (unpaid) economy. My alternative indicator studies suggest that the very poorest live on around $8-9 per day, which of course is still too low.

I also I have a problem with the way excessive per capita consumption is framed. I’m Australian. The per capita consumption of the average Australian is too high, ignoring anything else. But one can’t point the finger at Australia and say that if everyone on Earth consumed resources like the average Australian, the Earth would be trashed, as true as that statement is. Are the GHG emissions of the average Indian too high? According to one research organisation, they only became unstainable (can’t be sustainably replicated by every person on Earth) about ten years ago. Yet India is the third largest generator of GHG emissions in the world. Why? Because it is grossly overpopulated.

It is unfair to set the maximum permissible per capita consumption of something (a per capita planetary boundary) by dividing the maximum permissible aggregate consumption (an aggregate PB) by the world’s current population. It leads to perverse outcomes. For example, imagine a country with a small population but reasonably large per capita consumption that is right on the per capita PB (as calculated using the above method). Over the next decade it has ZPG and maintains its per capita consumption. It is being ‘ecologically responsible’ – yes? What if global population increased over the decade, thus reducing the per capita PB. It would appear to be irresponsible, simply because the ROW is irresponsible.

Per capita consumption matters, but population matters too, as Ehrlich’s I = PAT identity highlights. The per capita PB should be set at what is deemed reasonable for a single individual to live a long, happy, and meaningful life with an adjustment made to the per capita PB for individual countries based on historical consumption levels. High consumption countries would have their per capita PB adjusted downwards; low consumption countries upwards.

I believe the UNFCCC concept for GHG emissions should be extended to the nine planetary boundaries – a United Nations Framework Convention on Planetary Boundaries (UNFCPB) with nine individual FCs (we already have one FC for GHG emissions). Every nation would have caps imposed to reach the targets required for the world to operate within all nine PBs. I believe it is the only way to stay within all nine PBs and achieve it in a managed and peaceful way.

With caps imposed, nations would have to opt for a large population with low per capita consumption; a small population with large per capita consumption; or something in between. It would force countries to take population matters seriously (at last!). In particular, it would force countries like China and India to focus a lot of their attention on population numbers and countries like Australia (with just 27 million people in a country that is virtually the same size as the 48 contiguous states of the USA) to focus on per capita consumption, which is just what we want to achieve the goal of a sustainable and equitable world.

Cheers, Phil (and keep up the good work)