Tompkins County, the Finger Lakes Hub of Sustainability

by Dave Rollo

Canadice Lake, a jewel of the Finger Lakes region. (VisitFingerLakes, Wikimedia)

The Finger Lakes region of western New York State is distinguished by a series of long and narrow glacial valleys, dammed by moraine, that now contain lakes. Glacial scouring created some of the deepest lakes in North America, including Seneca, Cayuga, and Skaneateles lakes. These spectacular natural features give the region its identity.

The region features ample farmland and forest and a relatively sparse population. Tompkins County, in the heart of the region, has experienced a steady 0.5% per year increase in population. But nearly all the surrounding counties have stable or slightly declining populations. Nevertheless, growth pressures from sprawl and from large corporate land-use practices threaten the biocapacity of the Finger Lakes region.

Fortunately, four sustainability organizations in Tompkins County are active in challenging these growth-induced threats. These are in the City of Ithaca, in the town of Ithaca that partially surrounds the city, at Cornell University’s Office of Sustainability, and in the Tompkins County Sustainability Department. An additional asset is Sustainable Tompkins, an independent organization founded in 2004 that has expanded and rebranded itself as Sustainable Finger Lakes. It serves 15 counties within the region.

Overarching Principles

The Tompkins County Sustainability Department has set sustainability, regional cooperation, and fiscal responsibility as overarching principles of its 2004 Comprehensive Plan. (Officials updated the plan in 2015). These principles establish the vision that informs policymaking on housing, transportation, energy, climate change, and other issues.

Tompkins County’s Natural Features Focus Areas. (Tompkins County)

The plan’s first overarching principle states that the county “should be a place where the needs of current and future generations are met without compromising the ecosystems upon which they depend.” This directive informs the scale of development, and as a corollary, identifies natural areas within the County for preservation. The plan uses Natural Features Focus Areas as a tool for acquisition by both the county and land trusts, with the aim of preserving county green infrastructure.

The second overarching principle focuses on regional cooperation, extending the scope of concern beyond the Tompkins County borders. The plan aims to advance the progress of surrounding counties via a regional approach to sustainability. It devotes an entire page to the idea that “One of the greatest values of the Plan is that it provides a framework for voluntary partnerships and collaboration.” The Tompkins County government set the stage for regional sustainability more than two decades ago.

The third overarching principle deals with fiscal responsibility. Notably, and in contrast to many county comprehensive plans, this principle does not promote growth. Instead, it directs public dollars to maintenance of existing infrastructure. It sees jobs with living wages, investments in green infrastructure, and climate initiatives as prudent ways to mitigate future costs. It also calls for clustering new development into nodes to mitigate environmental and budgetary costs, an approach consistent with good stewardship of the public purse. In other words, the plan says that careful investment in sustainability is the foundation of fiscal responsibility.

The three overarching principles create the context for a range of sustainability policies and programs within the County. They also encourage efforts in the wider region. The principles have led to county successes in promoting compact urban form, in combating water pollution in the Finger Lakes watershed, and in banning hydrofracking.

Scuttling Sprawl

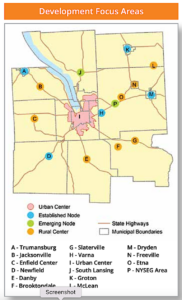

Tompkins County’s Nodal Development Areas. (Tompkins County Planning and Sustainability Department)

The Tompkins County Comprehensive Plan recognizes sprawl as a major threat to infrastructure budgets and to environmental health. The plan helps to address a key concern in the Finger Lakes Region: Farmland there is especially vulnerable to conversion to low-density development, according to the American Farmland Trust study “Farms Under Threat.”

Responding to the threat of sprawl, the Tompkins County Comprehensive Plan focuses on controlling growth pressures using nodal development patterns. Nodal development focuses new development in existing centers served by viable infrastructure, yielding high-density, mixed-use development.

Ed Marx, the former Commissioner of Planning and Sustainability for Tompkins County and one of the principal authors of the plan, observes that county governments in New York cede zoning control to the most local government authority, in this case small local municipalities. But he also noted that local governments use the plan as a template and guide for best practices in zoning control. “Nodal development and our Development Focus Area strategy serves as a guide—and as a guide, was less controversial to create and adopt.”

Citizens have also prioritized tightening zoning regulations. This has yielded successes in what municipalities call Development Focus Areas, county-designated areas for executing nodal development objectives. An example is the 2022 zoning restrictions in Danby, a town on the outskirts of Ithaca. Danby promotes cluster development outside of hamlets and preservation of farmland.

Another zoning victory came in the nearby town of Caroline, which previously lacked any zoning restrictions. After a contentious three-year debate, the Caroline Draft Zoning Plan was created. But its implementation was in question going into the November 2023 election. The contest pitted zoning advocates, who wanted to control encroachment from nearby Ithaca, against anti-zoning opponents. Citizens elected zoning advocates to the position of town supervisor and to three seats on the town board, assuring that the board will adopt the sprawl prevention code of the draft comprehensive zoning plan.

Stopping Farm Pollution and Fracking

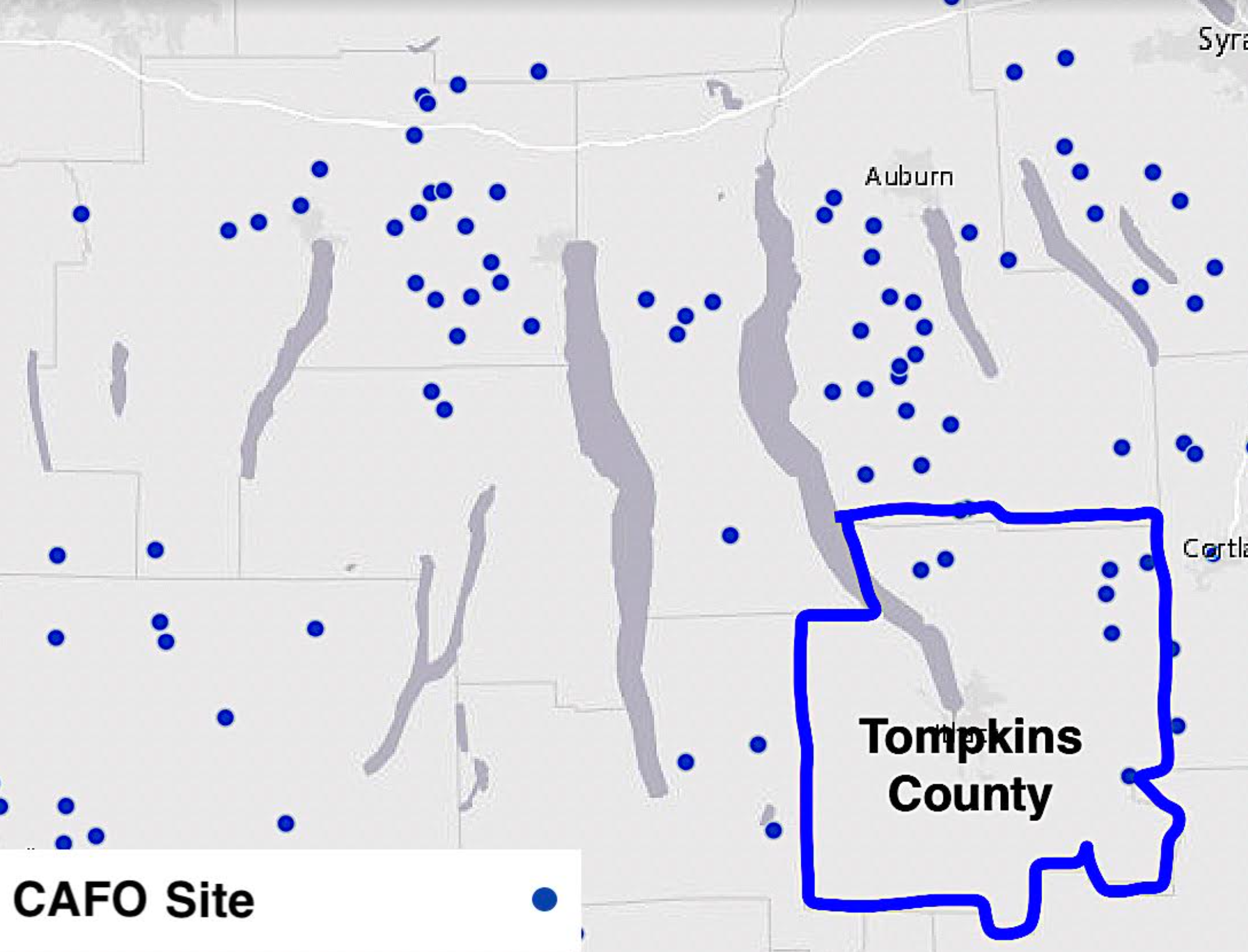

Most of the Finger Lakes Region is occupied by small family farms that raise dairy cattle. But dozens of CAFOs (Confined Animal Feeding Operations) are replacing family farms within the watersheds of the Finger Lakes. CAFOs create concerns for animal welfare in addition to numerous environmental problems. One is Hazardous Algal Blooms (HABs) caused by toxic cyanobacteria that thrive on nitrogen runoff from CAFOs and fertilized cropland. Toxins produced by the cyanobacteria foul the once-pristine lakes and kill fish. They have also infiltrated the drinking water of several communities, which has required the installation of expensive carbon filtration systems.

A grassroots effort by Finger Lakes region communities to protect the Seneca-Keuka Watershed resulted in adoption in 2022 of the Nine Element (9E) Plan. The plan aims to reduce the watershed’s nutrient load, which comes primarily from CAFOs.

Another noteworthy initiative is the Tompkins County Agriculture and Farmland Protection Plan. This initiative emphasizes protecting small family farms by helping them stay profitable as a strategy for strengthening local agriculture. While the program aims primarilyt to improve economic resiliency, it also has an environmental payoff, helping to reduce HABs. Smaller, less-intensive farming operations reduce waste volumes compared to the waste output of large-scale industrial farms.

Another noteworthy initiative is the Tompkins County Agriculture and Farmland Protection Plan. This initiative emphasizes protecting small family farms by helping them stay profitable as a strategy for strengthening local agriculture. While the program aims primarilyt to improve economic resiliency, it also has an environmental payoff, helping to reduce HABs. Smaller, less-intensive farming operations reduce waste volumes compared to the waste output of large-scale industrial farms.

The principles of the county plan also inspire sustainable land use and protect biocapacity. This is evident in the town of Dryden’s work to stave off fracking. Fracking is the process of drilling into and fracturing shale, which yields natural gas, but also contaminates groundwater. Bedrock in the region contains the uppermost range of the Marcellus Shale deposit. This is a methane-rich resource that the fracking industry has tapped as part of the “shale revolution.”

Dryden’s citizens formed the Dryden Resource Awareness Coalition and passed a town referendum opposing fracking. With legal help from area lawyers and EarthJustice, they prevented repeated attempts to open their community to fracking. Their work also resulted in a landmark anti-fracking judgment by the New York State Court of Appeals. The judgment served as a precedent to protect dozens of other communities throughout the state. The state legislature later banned all hydrofracking in New York state, thanks in great measure to the efforts that began in Tompkins County.

Promise of the Green Amendment

A potentially powerful tool for Tompkins County and the greater region is the New York State “Green Amendment.” Also known as the Environmental Rights Amendment, voters approved it by a 70 percent majority in 2021. It contains an important guarantee: “Each person shall have a right to clean air and water, and a healthful environment.” It’s the third such amendment in the country (joining Montana and Pennsylvania), although eleven other states have proposed similar provisions. The courts have yet to interpret how the amendment will be applied. But local activists have been disappointed so far by one case brought in the Finger Lakes Region.

The case was brought to limit the expansion of the Seneca Meadows Landfill, the state’s largest, which lies just a few miles north of Tompkins County. The landfill receives 6,000 tons of garbage per day from four states and Canada. It was due to close in 2025 because of lack of capacity, the landfill’s owners have applied to the State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) to extend its operation until 2040. They anticipate that an additional 32 million tons of garbage—16 years’ worth—will be buried at the site. Residents in the nearby towns of Seneca Falls and Waterloo suffer from the stench of the landfill. They also reside in a lung cancer cluster area, according to the State Department of Health, although the connection to the landfill is unclear.

In March of 2024, a citizens’ group called Seneca Lake Guardian filed suit against the DEC to address local health concerns. A previous judicial ruling found that the Green Amendment applies only to state government, in this case the DEC, not private corporations. And the DEC maintains that it alone has discretion to grant a permit for the landfill. The state Attorney General backs this view. The plaintiffs, led by Seneca Lake Guardian, are seeking an injunction from the state Supreme Court to block the permitting. The case is pending.

Local and Regional Collaboration

Tompkins County is a source of policy inspiration and test cases for the state. Just as fracking restrictions emerged in Tompkins County, so too has the Finger Lakes Region incubated housing support programs, density incentives, and regional climate policies.

One unique example of a county effort with potentially far-reaching impact is its work with the Cornell Cooperative Extension to support sustainable food systems. The program pays farmers directly for efforts to safeguard ecosystem services. These services include provisioning food and other natural goods, regulating ecological functions, and providing cultural support. They are essential for human well-being. Recognition that these services are part of the fabric of infrastructure ensures ecological protection, monitoring, and maintenance.

Ithaca Falls, one of Tompkins County’s treasured natural assets. (Stilfehler, Wikimedia)

An essential advocate in the regional multi-county approach to sustainability is Sustainable Finger Lakes. It acts as a “convener, connector, and catalyst to engage the grassroots and policymakers in redesigning how we work and live…” President Gay Nicholson derives inspiration from Gus Speth’s work on a systems approach to the multifaceted challenges of sustainability, and to limits to growth. The group is a key partner in organizing sustainability initiatives within a 15-county region. It links over 700 farms, businesses, government groups, and citizens’ organizations, providing a scaffolding for collaborative and synergistic efforts.

“We need to work more at the regional level,” Nicholson asserts, “because that’s the scale at which our foodshed, watershed, and economic networks tend to function. And working together regionally makes us stronger in many ways politically, such as advocating for helpful state policy shifts, and pushing back against exploitation by outside interests.”

Tompkins County plays a crucial role in establishing a systems approach to the social, economic, and environmental challenges of the region. It serves as the region’s sustainability hub, from which activities, planning, and policies radiate into surrounding counties like the spokes of a wheel.

The county is unique in having developed a consortium of groups that play specific roles within their domains of influence yet complement and work together under the umbrella of sustainability. Its hub-and-spoke model of sustainable planning is an inspiration for communities seeking to advance the wellbeing of citizens while protecting the natural assets essential to all development.

Dave Rollo is a Policy Specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

Thanks for such a detailed report! Other counties and municipalities that are working on new comprehensive plans, updated zoning, and sustainability policies can benefit from looking at these examples.

Thanks Dave for this interesting article.

You mentioned that Tompkins County has a growing population while some of the surrounding counties have a stable or declining population. I’m wondering if the Finger Lakes Hub of Sustainability has defined the region’s ecological carrying capacity and have they set limits to growth based on that carrying capacity. It sounds like growth is still welcomed as long as it meets certain harm reduction criteria.

I must apologize as I’m on the verge of retiring from a Canadian Local Government and I’m somewhat jaded. I’ve read a bucket of plans and policies over the decades from governments, their planning consultants and conservation organizations with lots of sustainable language while continually accepting and planning for more growth. Most of these plans and policies champion the protection of natural assets, discuss climate initiatives, recommend smart growth principles, express concern about food security, set urban containment boundaries and so on. But, they are still growing and limits to growth are never mentioned.

At best then, the sustainability plans and policies we have here are helping to take the edge off of decline and reducing environmental harm. That’s a start, but that’s not the same thing as sustainable – its “sustain-a-babble”. Check out the Qualicum Institute’s “sustain-a-babble” poster https://qualicuminstitute.ca/sustain-a-babble/.

Kindest regards, and I look forward to hearing more. Terri