Winds of Change in Lincoln County

by Dave Rollo

The plains of Oklahoma extending to the horizon. Tallgrass Prairie Preserve, Osage Hills, Oklahoma (Wikimedia Commons).

Rolling hills and wide-open plains typify eastern Oklahoma. Gulf Coast and Canadian air masses converge over these plains, creating a near-constant pressure gradient called the low-level jet (LLJ). The result is perpetual air currents in the central U.S. “wind corridor,” which make the region ideal for wind energy projects.

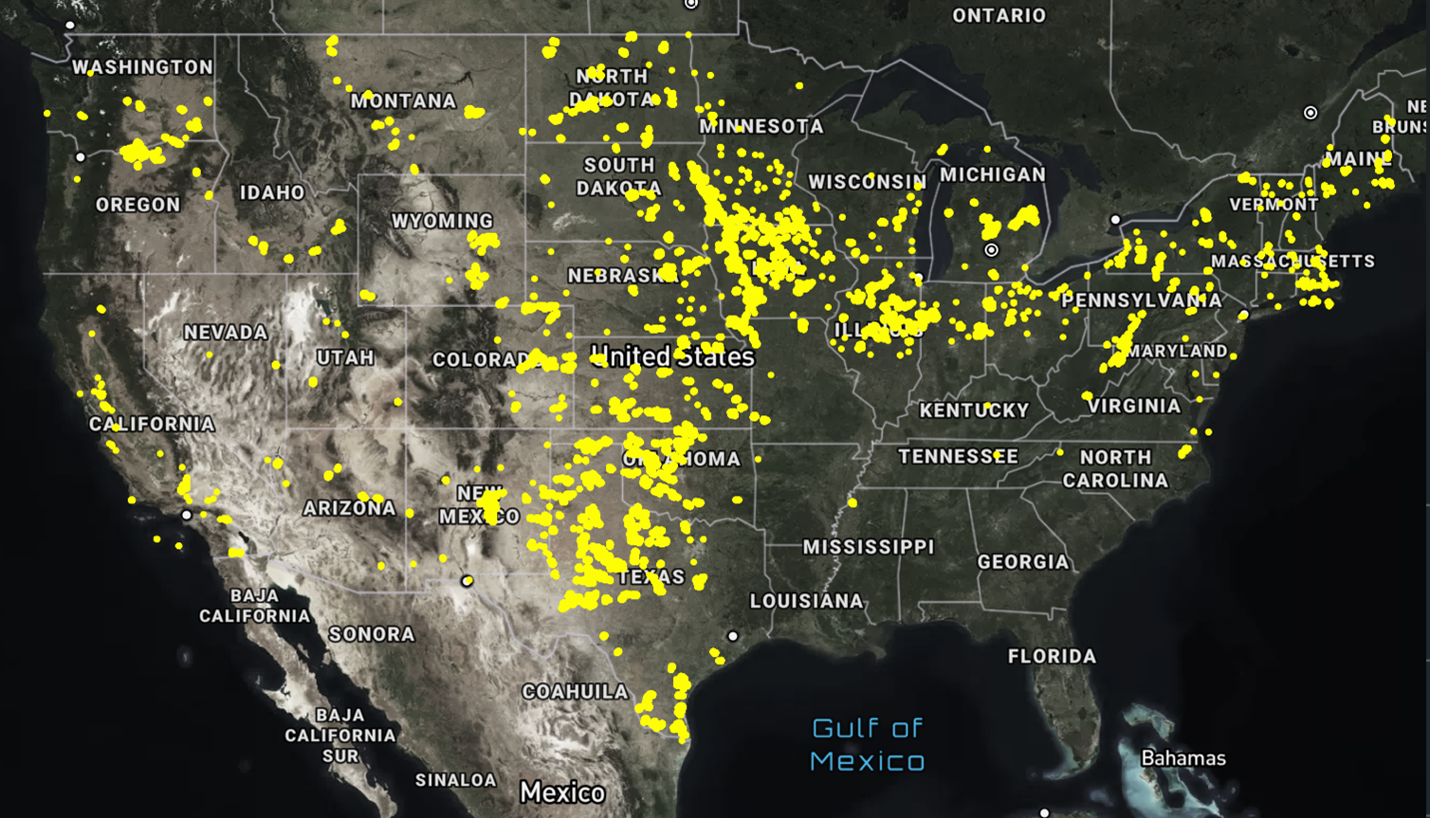

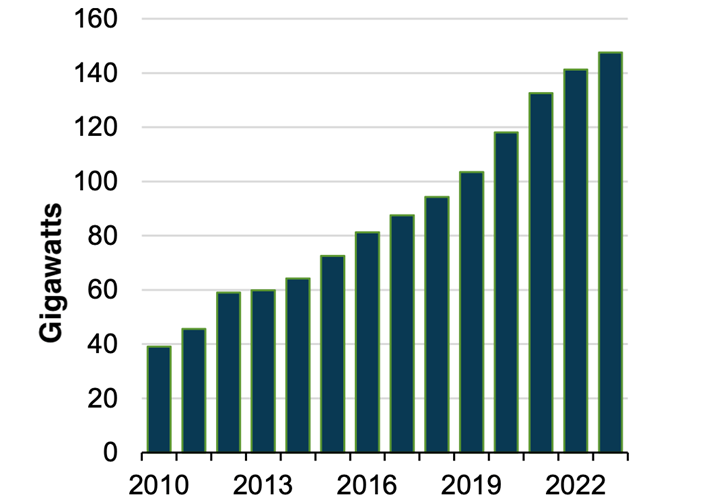

The United States’ top five wind-energy producers—Texas, Iowa, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Illinois—form a southwest to northeast diagonal through the center of the country. These five states generate greater than half the nation’s wind power. Their combined generation capacity has more than tripled since 2010, aided by federal policies and incentives that favor “green” energy.

Oklahoma’s growth in wind power is second only to Texas’s and features some of the world’s largest wind farms. The Traverse Wind Energy Center occupies over 220,000 acres in central Oklahoma. The Wind Catcher Energy Connection facility is currently under construction and will surpass Traverse to rank as the second-largest wind farm in the world.

Wind energy is one modest tool in the fight against climate change, and every tool counts. However, the development of wind energy has substantial impacts on the environment and communities. Many living amidst wind facilities describe harmful impacts, calling into question wind energy’s benign reputation.

With the number of wind turbines soon to reach six thousand, Oklahomans are beginning to object to more. Lincoln County, which has a population of 33,000 and lies in a rural stretch between Oklahoma City and Tulsa, is at the epicenter of the resistance. Lincoln County may well decide the fate of future proposals in eastern Oklahoma and beyond.

Turbines Moving East

Until recently, most of Oklahoma’s wind generation was located west of Oklahoma City, the state’s capital. Western Oklahoma is less populated, and its wind speeds are higher. However, eastern Oklahoma’s wind potential is also favorable, and multinational wind energy companies have recently targeted the region. The German company RWE, for instance, runs the 240-megawatt Prairie Wolf Wind Farm in eastern Oklahoma’s Hughes and Okfuskee Counties.

2023 map of U.S. wind farms (U.S. Department of Energy), most of which lie within the Great Plains Wind Corridor.

Lincoln County has been in the sights of two multinationals, Enel Green Power and Apex Clean Energy. Enel Green Power has proposed the 15,000-acre Cedar Run Wind Project in the central area of the county. Apex Clean Energy has proposed the 35,000-acre Sandstone Hills Wind Project in the county’s northern region.

These enormous projects caught the attention of Lincoln County resident Robbie McCommas and her husband Jeff in 2024, when Apex orchestrated a public meeting in Chandler, the Lincoln County seat. Robbie’s friends in western Oklahoma had alerted her to the downsides of living amidst wind turbines, which often tower over 600 feet above surrounding homes. These downsides include aesthetic impacts, unpleasant sounds, palpable vibration, and a “strobe effect” from the giant blades, which repeatedly block the sun as they rotate.

Many communities near turbines have reported health effects, and some researchers have found causal relationships. One of Robbie’s friends suffers from supraventricular tachycardia, a heart-rhythm condition. The pattern of his arrhythmia coincided with turbine operations. After failed attempts to control the illness with medication, his doctor recommended moving away from the wind farm altogether.

When Robbie attended Apex’s public meeting, she realized that it was less about information and more about recruitment of people willing to lease their property to the company. There was a great deal of confusion concerning the financial compensation for leasing one’s property. When Robbie circulated a clipboard to collect contact information for concerned citizens, people enthusiastically signed on. They asked, “When is the next meeting?” and “What are we going to do next?”

The Word is Out

Robbie had tapped into Lincoln County residents’ apprehension. “Everything took off very quickly,” she remembers. Soon, the local television station began inquiring. Over 500 people attended a public meeting in March, 2024. Speakers addressed the topic of wind power and citizens were empowered to critique the wind projects. The meeting organizers invited a number of public officials, but only one county official turned up. Robbie recalls, “The word got out very fast then, since by the time the coverage aired we had set up a Facebook page—No Wind Turbines for Lincoln County—for our neighbors to visit.”

A small portion of Blue Canyon Wind Farm in western Oklahoma (James Fleeting, Wikimedia Commons).

As word spread through the media, Robbie and Jeff began hearing from others who were affected by wind farms but couldn’t speak out. Robbie explains, “It is easy to see how everyone has been left out of the process. When lease contracts are signed, they include non-disclosure agreements, NDAs. That just adds to the level of secrecy.”

Jeff suspects that Lincoln County government was aware of companies’ attempts to gain access to private land through lease agreements. “Apex has been approaching county residents since 2016, and our local government wasn’t aware of it? Either they were and we were never told, or they were totally unaware for years. Neither of those possibilities are good.”

Jeff’s contacts in other parts of the state expressed disappointment once companies installed wind farms. One landowner who consented and signed a lease received a fraction of the compensation he expected. Others found that companies used their land for access easements, not turbines. They lived with the consequences of the turbines on neighboring farms but never received much compensation. Jeff notes, “We had lots of examples of bad outcomes, and we didn’t want to suffer like our neighbors had.”

Taming Wind Power

No Wind Turbines for Lincoln County has continued to gather steam, with members numbering over 2,100. The Facebook page posts examples of the downsides of wind farms as well as stories of neighboring counties that successfully resisted large multinational wind-power companies.

McIntosh County, lying about 40 miles east of Lincoln County, provides one such story. In a January 2025 letter to county commissioners, the company TransAlta communicated its decision to cancel its massive Canadian River Wind Project. Additionally, in December 2024, a federal judge ruled that an 8,400-acre wind farm installed in neighboring Osage County had to be removed. The wind companies involved—Osage Wind LLC, Enel Kansas LLC, and Enel Green Power North America Inc.—had failed to acquire the permits necessary for installation. Moreover, the ruling required companies to pay a penalty to the Osage Nation, as the installation impacted their reservation.

Jim Shaw, part of a wave of local politicians focused on opposing the expansion of industrial wind projects (Oklahoma House of Representatives).

Activists and policymakers in Lincoln County found encouragement in neighboring counties’ successes. In 2024, the Lincoln County Commissioners voiced support for a wind farm moratorium, though they failed to take action, citing legal constraints. In November, Jim Shaw, a member of No Wind Turbines for Lincoln County, defeated a powerful incumbent and is now Lincoln County’s state representative. Shaw ran an explicitly anti-wind-farm campaign, pledging to “preserve the land, livelihood, and legacy of Oklahomans.”

Since taking office in 2025, Representative Shaw has filed a number of bills that, among other things, place a state moratorium on wind energy in Oklahoma. Meanwhile, Tim Turner, another new state representative whose district includes McIntosh County, has filed House Bill 1989. This milder bill would prohibit placement of turbines within two miles of “a wildlife refuge, wildlife management area, a body of water regarded as a habitat for migrating waterfowl, or any active aquifer.”

The Changing State and Federal Landscape

These bills at the Oklahoma statehouse are a sign that the pushback on wind turbines is reaching a critical mass statewide. If the legislation passes, it will need the governor’s signature. The candidates’ positions on wind farms may well decide the gubernatorial election in the fall of 2025. Big wind advocate Governor Ryan Stitt has reached his term limit and is retiring. Governor Stitt is facing dissent for his policies from Ryan Walters, a former member of his administration who currently serves as state superintendent of education. Walters is ardently against large wind farms and, although not yet declared, is one of several candidates expected to run next year to replace Stitt.

State resistance to wind farms, and wind energy in general, is occurring in lockstep with federal policies that will limit federal leasing—of offshore wind facilities, for example—and end subsidies that the industry relies on.

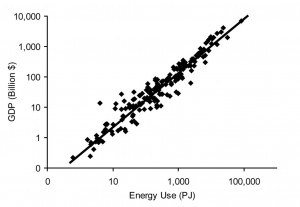

Is this resistance to “green energy” a bad thing, from a steady-state perspective? Yes, and no. Wind has its place in a palette of options for our energy needs. However, “alternative energy” has been used as a palliative to ignore the implications of economic growth.

Wind power has more than tripled in the past fifteen years and now makes up 3.5% of the total U.S. energy portfolio (U.S. Energy Information Administration, Electric Power Monthly).

Despite the phenomenal growth in wind turbines, now numbering over 73,000 across the U.S., their total energy generation remains under 3.5% of national consumption. What’s more, the lifespan of a wind turbine is approximately 20 years—similar to that of a solar panel—meaning companies must reinstall these devices every other decade. As expert Nate Hagens notes, rather than using the adjective “renewable,” we should use “replaceable” when referring to wind energy.

That’s not to say that environmentalists should throw in the towel in the fight to transition away from fossil fuels. Neither can Lincoln County be expected to throw in the towel in their fight against strobing sunlight, unwanted sound and vibration, and obscured views of the land they’ve called home, in many cases, for generations. Are these two interest groups at an impasse? Not if they work together toward a steady state economy; the only real path to reduce fossil-fuel use without an exorbitant increase in wind turbines.

Dave Rollo is a policy specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

Dave Rollo is a policy specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

The vast majority of solar and wind capture ought to just be on each and all of our roofs (whether residential or commercial), thereby keeping production spread out so less vulnerable to attack/mass failure and keeping it in our hands rather than in the hands of huge corporations who’ve regularly taken advantage of consumers.

Yes, I’m in total agreement with you. Having these deployed on a smaller scale to increase efficiencies of building energy use, instead of the industrial model of super-scale is a better strategy for society.

Yes but in many cases wind doesn’t blow sufficiently where residential areas are.

The wind that blows through those states is a common good, similar to say a desert spring. The corps are hoarding this benefit for their owners to the detriment of the locals. In a steady state it would be so much better if a commonly owned cooperative was licensed to run the windfarms, with the benefit being passed to consumers in lower prices. Consumers could then reduce their working week with the saving, living enhanced lives while reducing impact. This ideal scenario is a dirty world away from current reality where all the benefits of the green energy transition are being guzzled by the exponential growth of power hungry data centres.

To think there are 73,000 wind turbines despoiling the American landscape and affecting some people’s health for the sake of 3.5% of the nation’s energy consumption when a 3.5% decrease in energy consumption could be achieved with minor lifestyle (energy demand) changes. But, no, we are told that we must increase supply to match increasing demand to maintain the growth imperative. Beautiful desert landscapes with crucial ecological significance are also being slowly covered up with solar panels. A case of destroying the planet and quality of life to save the planet – what is really an attempt to save a high consumption lifestyle achievable for the moment prior to ecosystems collapsing en masse.

People need to understand that it’s the scale at which we do everything that matters much more than the way we do individual things, as important as the latter is. A transition to renewable energy won’t, by itself, solve the ecological (excessive scale) crisis. As Herman Daly used to say, our resource use policy focuses on reducing the resource-intensity of GDP to the almost total exclusion of reducing aggregate levels of production and consumption (GDP).

My F = PAR work (a variation on Ehrlich’s I = PAT, where F = footprint; P = population; A = affluence or per capita GDP; R = resource-intensity or footprint-intensity of GDP; so that F = P x GDP/P x F/GDP) shows that, at the global level, we have halved the footprint required to produce a dollar’s worth of Gross World Product (GWP) over the past fifty years by changing the way and increasing the efficiency of doing things (we have halved the value of R). Great news if only P and A had not both doubled over the same period, which has led to the doubling of humankind’s footprint. Whereas the global footprint was below global biocapacity around fifty years ago (ecologically sustainable), it is now 1.75 times global biocapacity (75% larger and therefore ecologically unsustainable). The Jevons’ Paradox in full display.

I’m in full support of people resisting wind farms and alike to defend their quality of life and the beauty of our landscapes. Here, in Australia, we are going through an urban battle between people protecting what they have and those telling them that their Australian ‘way of life’ (open spaces and houses on quarter-acre blocks of land) must be surrendered to permit the construction of high-rise apartments (high density living) to help resolve a housing affordability crisis fueled largely by a 1.5-2% population growth rate. The ‘resisters’ are being unfairly referred to as selfish members of a ‘not in my backyard’ movement (NIMBYism). They are being told to “suck it up!” You know there is a growth fetish when the desire to keep increasing GDP (and Australia’s population) is considered more important than guarding an enviable way of life.

Amen from Brisbane. Last week I attended a screening of a BBC doco called ‘Can Degrowth Save the World?’ and during the Q&A, when population came up the issue of immigration was considered to be ‘too sensitive’ to talk about, probably because most in the audience are Greens sympathizers. Mass immigration to Australia causes growth here and does nothing to discourage it in the source countries. But the reasoning is that we here should impoverish ourselves to the level of 3rd World Countries to atone for our ancestors’ sins of trade and colonization… as if Australia was a colonizer, not a colony. Degrowth and the Australian dream of home ownership are compatible and degrowthers will get nowhere until they realize this.