Building a Steady State Economy in a System Evolved for Growth

by Brian Snyder

If you’ve been on the internet recently you’ve been exposed to Tiger King, the wildly popular Netflix series that revolves around the conflict among a bizarre set of humans feuding over the proper way to hold big cats in captivity. Watching the show is a bit like watching a train derail in slow motion, but for our purposes what is important is that it illustrates the discrepancy between the way the world is and the way the world ought to be. There are no heroes in Tiger King, and indeed a limited number of characters that might be considered psychologically whole, but in the final episode, one of the saner characters notes that this years-long feud and a resulting 19-count federal indictment has wasted millions of public and private dollars which could have been better spent on protecting the few remaining tigers in the wild. That is, he notes the discrepancy between the way the world is and the way the world ought to be.

David Hume’s is/ought fallacy: an ever-present danger in thinking about economic growth. (Image: CC0, Credit: Allan Ramsay)

It seems obvious that Tiger King does not depict the way the world ought to be, but the confusion between is and ought is so common and pervasive that David Hume, the brilliant 18th century Scottish philosopher called it the is/ought fallacy. We observe the way the world is—perhaps in our economic systems—and assume that is the way the world ought to be. Doing so is no more rational than observing the characters of Tiger King and assuming they provide exemplars of human ethics. Put simply, none of our data about the world describe how the world should be.

The fundamental reason that using data (is) to inform ought is fallacious is that the way the world is (the data) is a result of evolution. Human cultures and economic systems evolved through natural selection in much the same manner as our physical traits, and taking ethical advice from nature is problematic because evolution is value-neutral. Evolution has no way to produce objectively good or bad behavior, just beings that are good at reproducing. Thus, evolution has no means for producing right and wrong. Using it to inform our ethical choices is akin to entrusting Bernie Madoff with our financial planning: there is simply no reason to trust evolution to know right from wrong.

This is important for those interested in a steady state economy because a steady state economy is not natural, or in fancier language, it is not an evolutionary stable strategy. Imagine two ancient societies living near each other, one growth society developing new technologies for farming and raising their population size, while the other steady state society lives a quieter, stable existence. In this empty world of vast resources, the growing society continues to grow and absorb resources until it outcompetes and assimilates or annihilates the steady state society. We have witnessed this process occur throughout history as more industrialized societies have replaced less industrialized ones. Thus, for humans, what has been selected by evolution, what is natural, is industrialization and growth.

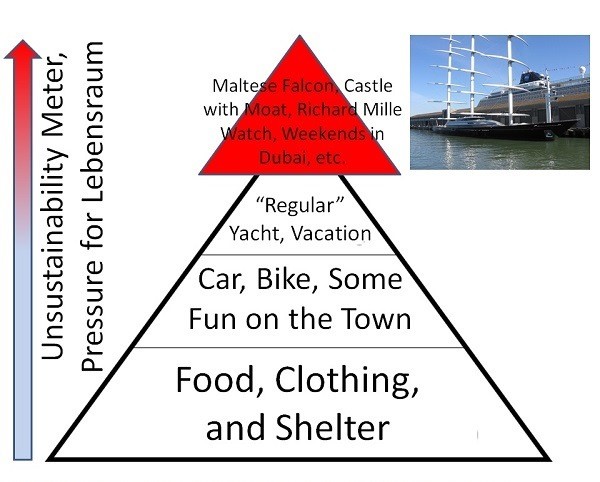

Of course, that does not say whether industrialization and growth are good. Nor does that imply that growth is adaptive in the current world full of 7.6 billion people. But it does imply that we have evolved for growth. Understanding this may be important for a transition to a steady state because it gives us an idea of the scale of the challenge. If human populations have been selected for millennia to grow then there may be both genetic and cultural adaptations that favor growth. For example, we might view greed as an adaptation; greedy individuals and greedy societies may be more likely to extract more material and energy from the environment and may thus have more surviving progeny than less greedy people or groups. Similar logic might apply to territoriality, war, and economic/political systems like democratic capitalism and Marxism. The societies and peoples that grow the fastest outcompete the others and their genetic and cultural traits get passed on to future generations.

But if this is the ultimate explanation for our unsustainable societies, what can we do about it? Perhaps it might start with the recognition that the way we have evolved is not objectively good. That is, that we have created a rapid-growth economy because we are evolved to have done so but that does not mean such an economy is right. Our current economic system was not handed down by God. Nor, of course, does that imply that a growth economy is evil. Instead, we might see the system that we live in today as one of a number of options; we might understand that none of these options are objectively good or bad, and we might seek to discern which economic system is, in our collective subjective opinions, preferred. That is, the first step is understanding that we have a choice about what sort of economic system we want and that any such system will have tradeoffs.

Second, we must understand that changing economic systems has occurred numerous times through history and so can occur again. The communist revolutions in the 20th century are the most obvious example, but the birth of capitalism in the 17th century was just as revolutionary. A transition to a steady-state system would be arguably less transformative (at least, as proposed by CASSE) than either of these revolutions. In other words, economic systems are a product of evolutionary change, and thus, they change over time.

Third, the adaptive view of economic systems implies that there are traits at both the personal and societal level that keep us in the growth economy, and that changing from a growth to a steady state economy would require both individual and collective change. At the individual level, much of what pastors call “sin” can be understood as an adaptation for growth and reproduction. Greed and jealousy can be viewed as traits, either learned or hardwired, that propel us to consume more resources and thus increase our survival and reproduction. Thus, to shift from a growth to a steady state economy will require, not a shift in our ethical principles, but a recollection of the ethical principles we already claim to hold. This is a point Herman Daly and John Cobb made insightfully in their book, For the Common Good.

However, the adaptation toward growth is most visible in groups and thus group-level change is especially critical. But how do you move a social group that is adapted towards growth to shift towards a steady-state system? This question is especially difficult. Herman Daly, Phil Lawn, Brian Czech, Rob Dietz, Dan O’Neill, and other steady-state economists have addressed the policies that would need to change, but how does one accomplish this change, especially if the system is evolved toward growth. Perhaps rephrasing the question would be helpful; assuming that humans are evolved towards growth, how do you reverse evolution?

Biological systems, including human social systems, evolve to be adapted to their environment. Humans are adapted to a growth environment because we evolved in an empty world. In the fuller world in which we now live, growth may be less adaptive. Already, we have seen extraordinary declines in human fertility rates around the world and it is possible that this represents an evolutionary change in humans towards a lower-growth system. Thus, perhaps the relevant question is less, “how do we transition to a steady state economy?” and more, “how do we modify the human environment to lead humans to evolve into a steady state economy?” That is, what are the environmental factors that lead social groups to favor decreased reproduction, decreased consumption, and decreased work hours and how do we build societies that foster those traits?

Brian Snyder is an assistant professor of environmental science at Louisiana State University and CASSE’s LSU Chapter director.

Brian Snyder is an assistant professor of environmental science at Louisiana State University and CASSE’s LSU Chapter director.

Excellent analysis leading to a crucial question for advancing the steady state economy: Will we have any evolutionary tendencies on our side? And, might we even do something to construct or modify the evolutionary leverage points? This article should serve as a launching point for ongoing discussions on this topic.

The next book off the Steady State Press—Uncommon Sense by Peter Seidel—will probe these evolutionary issues as well.

Hi Brian,

“Will we have evolutionary tendencies on our side” is a great question. I think we do. Because we are so social, we have evolved through both individual and group-level selection. The group-level selection may have left us with traits that allow us to put the interests of the group above our own interests (altruism). Those altruistic traits may help us respond to our environmental crises.

Thanks for an interesting and provocative idea. Is it not true, however, that in a natural ecological system, overly dominant species run out of resources and lead to a population crash? One of my takes from reading Daly and Cobb was the need for a negative feedback in the economic system. For a while I had hoped that Peak Oil would do it, but the climate emergency likely will intervene before we run out of fossil fuels. Pandemics such as the current one might also serve, but either one of these alternatives carries an extreme burden of human suffering. Can we design policies to reach the same end, while maintaining a reasonable level of prosperity? How would we convince policy makers to adopt them?

No growth rate can seem more explosive than that of bacteria when all the conditions are right. They are the oldest, most widely spread, and most numerous lifeform : Evolution’s star pupil.

But equally, no lifeform can grow more slowly, such as in an hostile underground environment, than bacteria.

Survival long enough to reproduce is evolution’s only measure of success : and that could mean that a slowed down steady state survival is the best option for us too, just as it is for many bacteria that have hung on for billions of years, surviving (just barely) but surviving none the less, underground….

I like the philosophical background explaining that nature has no morality, that there is no ‘right’ of ‘wrong’ (reminds me of the divergence of opinions with share traders who claim ‘greed is good’. But i would qualify a general comment that biological systems have evolved for growth by suggesting that ‘biological systems have evolved to maximise reproductive throughput’. If one looks at the real world, one finds actually that most systems are in a fairly well circumscribed steady state – I look at coral reefs (on which i have worked for 50+ years) and while individual populations may fluctuate, on a local basis, the total reef ecosystem is fairly stable (over time spans longer than a research grant).

I think we need to educate the doyens of industry that, while competition is necessary, and individual companies (even industry sectors) will come and go, and replace each other, there is really no physical, economic or biological imperative that the whole system needs to grow. This of course will entail a paradigm shift away from the idea that we need a growing consumer base to provide a growing market source and hence a growing GDP (or whatever measure one would use to estimate gross productivity).

Stable ecosystems exist in nature, so stable economies can also exist.

But, as Brian states “Humans are adapted to a growth environment because we evolved in an empty world”. So, whether our behaviour is socially or even partly genetically driven, one of the hallmarks of a civilised society is that we bring some of our intrinsic behaviours under control – for the benefit of society as a whole. Surely we can also do this with our economic systems.

The answer to Brian Snyder’s question of HOW we do what already know is the right solution is the same answer it has always been. Educate and agitate. We spread the word, emphasizing how the current growth system is destroying the natural base on which civilization rests, and we organize politically.

Kent D. Shifferd, PhD

Author, From War to Peace (McFarland Pubs)

forthcoming: Planetary Emergency: Environmental Collapse and the Promise of Ecocivilization

Great article and idea, useful fodder for my son who is currently pursuing his Masters in philosophy. As I read the article, the same idea as Dr. Goldman pointed out kept coming to mind, “one of the hallmarks of a civilised society is that we bring some of our intrinsic behaviours under control – for the benefit of society as a whole”.

Another concern, as a steady-state economy is put into practice, would be that nagging concept of the zero sum game, that there is only so much pie and everyone will want their piece, and will do whatever they can for it. While I understand that once a steady-state economy (and population) is reached, there will be relatively more pie for each of us, the transition will be complicated. Would a steady-state economy complete with de-growth be possible in one country at a time? Would a country and its inhabitants willingly give up their piece of pie? Even if societies agreed, how patient would they need to be and how would we measure success, providing positive feedback?

I’m fairly new to CASSE, has this concern been addressed elsewhere? I see some possible solutions for this problem, but it would involve multiple countries, if not all, transitioning to steady-state economy at once.

Thank you for addressing these critical issues.