Carbon and Canada’s Cars: “Business As Usual, Electrified”

by Bart Hawkins Kreps

Auto industry voices in Canada have made headlines recently by urging a longer timeline for the transition to electric cars. We should hope that Prime Minister Mark Carney does not give in to this demand.

Yet even if Canada’s federal government sticks to the current policy, and Canadian new car sales are 100 percent zero-emission by 2035, carbon emissions will decline much more slowly than the world needs. That is due to the auto industry’s particularly pernicious strategy for continued growth.

If you can’t sell more, sell bigger.

The industry can’t keep boosting unit sales in a country where almost everyone who can drive, does drive. But they can boost revenue by selling bigger, heavier, more expensive vehicles when consumers need to swap their old vehicles for new ones.

With that strategy, Canada’s auto industry has done its part in maintaining the growth of gross domestic product (GDP). But the GDP isn’t all that’s growing. Pedestrian deaths and injuries are growing, tire particulate emissions are growing, traffic congestion is growing, and consumer debt (due to auto loans) is growing.

CO2 emissions from cars are holding steady and should start trending down over the next five years. However, a “Business As Usual, Electrified” transition will reduce emissions far too slowly to meet the climate-crisis challenge.

Car Bloat in Canada

Statistics Canada figures show that unit sales of passenger vehicles grew just over 20 percent between 2010 and 2024, while population grew 21 percent. Auto sales revenue, however, grew by over 100 percent.

Price tags have soared because the mix of new cars has changed drastically. Most new passenger vehicles are categorized as “light trucks”—SUVs and many models of pick-up trucks. But “light trucks” is a euphemism we should translate as “huge cars.” Most of them are used almost entirely to haul around one or two persons, just like small cars do.

In 2010, the huge-car segment was 54 percent of the Canadian market. By 2024, huge cars made up 87 percent of new passenger vehicles. This trend of “autobesity” or “car bloat” has significant implications for Canada’s strategy to reduce carbon emissions by electrifying vehicles.

In 2010, the huge-car segment was 54 percent of the Canadian market. By 2024, huge cars made up 87 percent of new passenger vehicles. This trend of “autobesity” or “car bloat” has significant implications for Canada’s strategy to reduce carbon emissions by electrifying vehicles.

First, if the auto industry maintains Business As Usual, the vast majority of internal combustion cars sold between now and 2035 will be huge. They will have correspondingly high tailpipe emissions well after 2035. These emissions are often termed “tank-to-wheel” emissions.

A second emissions category is termed “well-to-tank” emissions. Gasoline or diesel fuel goes from oil wells or mines through an extraction-refining-distribution chain. This adds significant emissions for every liter of fuel burned.

An analogous category—“well-to-grid” let’s call it—exists for electric vehicles (EVs) when electricity is produced by coal- or gas-fired generators. Canada’s grid is powered predominantly by hydro or nuclear power, though, so well-to-grid is not a major category of EV-fleet emissions. (That could change if Canada adopts the “all the above” approach to energy taken by the United States, for example.)

There are also substantial carbon emissions in the manufacture of cars. These emissions are higher for larger cars, and ironically, higher for electric cars than for gas- or diesel-powered cars. If most new cars continue rolling off the assembly lines huge, carbon emissions from auto manufacturing will go up between now and 2035. That will remain true until the carbon-intensive industrial processes in the manufacturing chain are also electrified.

Finally, if Canadians continue to buy as many cars as they do now and drive them as far each year, the fleet of huge cars will continue to take up more roadway surface. Road construction is itself a significant source of carbon emissions.

Beyond the Tailpipe

What will it really take for Canada’s auto industry to reach zero emissions by 2035? To answer this question, I projected six scenarios using a carbon-emissions calculator developed by the International Energy Agency. I estimated tank-to-wheel, well-to-tank, and auto manufacturing emissions in each of the six scenarios.

I incorporated road construction into my projections, using a Statistics Canada emissions-intensity per dollar estimate, multiplied by total road-construction expenditures for 2024. Passenger cars account for 91 percent of total vehicle kilometers driven, while heavy trucks and buses account for 9 percent. However, trucks and buses individually take more road space than cars. Therefore, I assigned 70 percent of road-construction emissions to the car fleet. (I did not find adequate data to estimate carbon emissions from road maintenance, which would make the analysis closer to complete.)

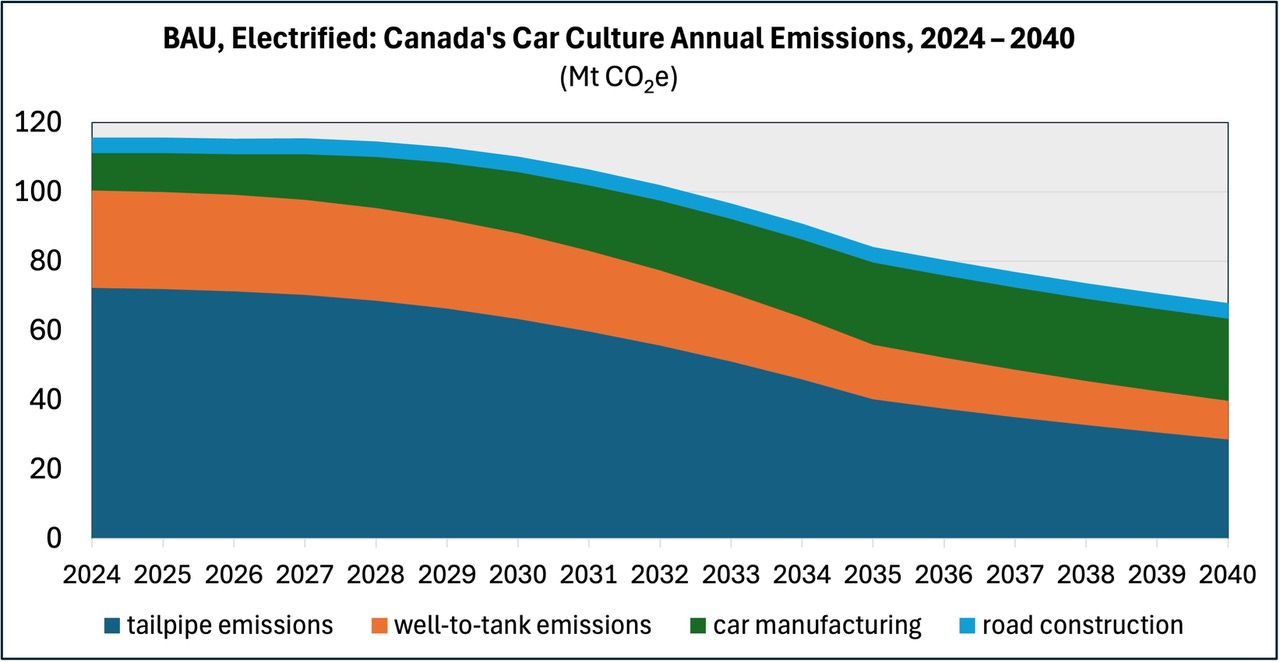

I estimated passenger-car fleet direct tailpipe emissions at about 72 megatonnes (Mt) of CO2 in 2024. This is slightly less than Environment Canada’s estimate of 74 Mt in pre-pandemic 2019. However, when I added the car fleet’s share of emissions from the extraction-refining-distribution chain, from auto manufacturing, and from road construction, car-sector emissions came to over 115 Mt. That’s a 60 percent increase over the tailpipe emissions alone.

If Canada’s goal of 100 percent EV sales by 2035 is met, total car-fleet emissions will still drop only 41 percent by 2040.

How will this change over the next 15 years? My “Business As Usual, Electrified” (BAU Electrified) projection through 2040 includes two somewhat optimistic assumptions. First, that electrification proceeds on schedule—20 percent of new cars being EV by 2026, 60 percent by 2030, and 100 percent by 2035. Second, that car bloat gets no worse (but also no better) through the coming years. The car/light-truck mix of new vehicles, and the vehicle sizes within these categories, remain exactly as in 2024. Importantly, however, this would mean that the average size of vehicles on the road would continue to increase. This is because the smaller sedans bought ten years ago would be replaced by large SUVs and pickup trucks.

Based on these assumptions, I projected that Canada’s car-fleet emissions would be 41 percent lower in 2040 than in 2024 in Scenario 1 (BAU Electrified).

A 41 percent drop may sound impressive. But climate experts have warned for years that we must reduce global warming emissions by at least 43 percent by 2030. So, a 41 percent drop by 2040 is dangerously inadequate.

Departures from Business As Usual

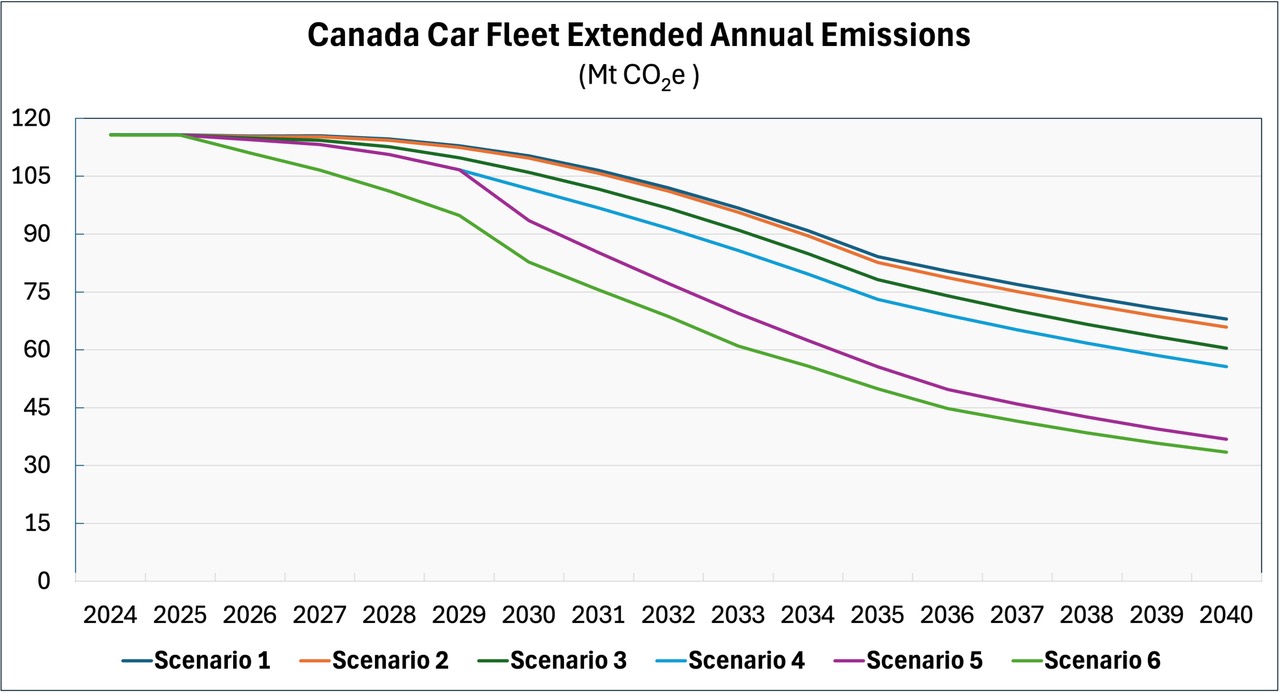

Making even modest changes to passenger-transportation rules could reduce these emissions significantly faster. I projected five additional scenarios, the best of which shows total car-fleet emissions dropping by 71 percent by 2040.

Modest changes to a “Business As Usual, Electrified” scenario would bring down car-fleet emissions by 71 percent by 2040.

Scenario 2 is only slightly different from BAU Electrified. It assumes a 98 percent zero-emission electric grid compared to Canada’s current national average of approximately 84 percent zero-emission.

In Scenario 3, the sedan/light-truck mix is dialed back to 2010 levels between 2026 and 2030. In Scenario 4, the sedan/light-truck mix is dialed back to 1979 levels between 2026 and 2030.

Scenario 5 builds on Scenario 4, except that vehicles within the sedan and light-truck categories drop modestly in size. In addition, I projected new-vehicle sales and average kilometers driven as dropping by 3.5 percent per year starting in 2030.

Finally, in Scenario 6 the annual vehicle-kilometer figure begins dropping by 3.5 percent per year in 2026. In Scenario 6, not only have CO2 emissions dropped by 71 percent by 2040, but the drop begins much sooner. The result is that cumulative emissions over the whole period are much lower.

Rising Demand for Electricity

More electricity means more infrastructure, such as the controversial, $16-billion Site C Clean Energy Project. (CC BY-NC 2.0, Province of British Columbia)

Car bloat is likely to pose one more serious challenge in the effort to shrink overall CO2 emissions. A fleet of huge electric cars will add greatly to demand for electricity, at a time when we are also working to electrify other important sectors, such as home heating. We won’t have enough renewably generated electricity to meet all these demands for many years. Therefore, a rational policy would conduce moderate levels of new electricity demand.

I calculated that a Canada-wide EV fleet matching the BAU Electrified scenario would require 68 TeraWatts (TW) per year. A fleet of mostly small EVs driving about 60 percent as many kilometers a year (close to Scenario 6) would require only 32 TW per year. Either way, this is an almost entirely new source of demand, as we scramble to convert other carbon-intensive sectors simultaneously. But it would be much less challenging to build out a grid capable of providing 32 TW rather than 68 TW. A smaller grid build-out will likewise require less environmentally destructive mining for critical metals.

Business As Usual Is Killing Us

There are many reasons besides carbon emissions to conclude that a “Business As Usual, Electrified” strategy is a bad route. The huge passenger vehicles now dominating the roads compound the danger to pedestrians, cyclists, and anyone driving a smaller car.

Huge passenger EVs need huge batteries—and thus demand a rapid, reckless increase in critical-mineral extraction.

A lithium mine in South America’s “Lithium Triangle”: The impacts of the energy transition are invisible to many consumers. (CC Attribution ShareAlike 2.0, Reinhard Jahn)

Huge EVs, since they are heavier than corresponding internal-combustion vehicles, create more dangerous particulate emissions from tire wear.

A fleet of huge cars takes up more road space, increasing traffic congestion.

And, huge cars chew up the roads faster, entailing more road construction and repair.

So, we should support the Canadian government’s plan for new-vehicle electrification by 2035. However, we should also demand that new vehicles be smaller, that the number of cars on the road gradually drops, and that vehicles drive fewer kilometers annually. There is a wide range of policies designed to achieve these goals. CASSE’s Sustainable Transportation Act, for example, includes provisions to get passenger vehicles and freight trucks off the road. It also discourages the purchase and use of the largest passenger cars and trucks.

The sooner such policies are implemented, the better—for drivers, non-drivers, our cities, our roads, our waters, our atmosphere, our future.

Electrification is an important and necessary step for a sustainable, healthy future, but growth-driven Business As Usual—even Electrified—is killing us.

Bart Hawkins Kreps is a Masters of Environmental Studies student at York University in Toronto. This article is based on research presented at the International Society for Ecological Economics/Degrowth conference in Oslo, Norway in June 2025.

I’m hoping that people in North America can shake off the (highly effective) marketing of car companies and see the recent generations of “light trucks” for what they are, on a purely self-interested level:

1) Irrationally expensive – here in California, I see some of the newer truck models costing over $100,000 USD. This is madness.

2) Expensive to operate. Not only do these vehicles guzzle fuel, they seem plagued with breakdowns and repairs. Listening to new truck owners, they seem to be constantly having their white elephant in the repair shop. My hunch is that the truck makers rush too much untried technology gimmicks into these vehicles, in an effort to justify their enormous mark up, and this untried tech is often buggy.

3) Surprisingly unsafe to one’s family / friends. I recently had to drive a new oversize truck for work, a company vehicle, to move some computer and data center gear about 15 kilometers. I was quite surprised at how poor the visibility was. There is a backup camera, but looking forward it’s really hard to see what’s directly in front of you. I can see why there has been a rash of truck owners killing their own small children. Also, visibility to one’s rear quarters is almost non-existent. Changing lanes on a busy freeway is best simply avoided, for safety’s sake

4) Finally, these $100K things are surprisingly un-exciting to drive. During my 15K data center errand driving one, I thought, well, there must be visceral appeal to these things.. let’s see how it accelerates. The answer: meh. No “excitement” there whatsoever.

The only, literally the only, solid performing characteristic of these planet-destroying vehicles is they seem to have pretty good air conditioning. That’s it.

I hope that drivers in Canada and elsewhere can learn to go through the exercise of thinking what their actual requirements are, and avoiding these oversized vehicles. And remember, walking and public transit is better for your own health.

Nice commentary, based on direct experience, to add to the article. I would add one word to the accurate conclusion that “walking and public transit is better for your own health” How about “walking, bicycling and public transit”?

The idea of ‘business as usual’ – that ‘business’ must generate profits at any cost, must change if Canada’s auto industry is genuinely committed towards reaching reaching zero emissions by 2035 as pointed out by the author. With a few changes, this article could apply to most other countries as well. Climate change has no borders. Unless world countries understand this, set aside their differences, and work towards sustainable solutions, no meaningful change can happen.

thanks for great article Bret.

EVs don’t have tailpipes but they still create non-tailpipe emissions (NTPs) from wearing down of brakes, clutches, tyres and road surfaces, and suspension of road dust.

NTPs are dangerous to health and under-recognised (of course – the industry wants business as usual, just a change in technology).

SeeOECD report

https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2020/12/non-exhaust-particulate-emissions-from-road-transport_707739b7/4a4dc6ca-en.pdf

Otherwise think of system change, with active and public transport, not just new vehicles.