Climate Engineering: Doubling Down on Bad Habits

by Gary Gardner

Let’s not mess with such perfection. (Wikimedia)

Social psychologists tell us it takes about 66 days to form a new habit. In my experience that’s only half true. Sixty-six days to form a good habit, yes, but about 66 hours to form a bad one. If I reach for a donut at breakfast, then do the same the next two days, I seal the deal and establish a habit of bad eating. And the dynamic has an insidious way of spreading. Soon I skip workouts, watch too much TV, and succumb to other indulgences. Poor choices beget poor choices, in a rapidly descending spiral.

We might frame climate engineering in the same way, as the latest in a downward spiral of bad economic choices. Our original sin was committing uncritically to growth. Then we doubled down using the power of fossil fuels. Now we flirt with climate engineering, a set of technologies that are expensive, risky, and often unproven, as an extension of our fossil energy addiction. Down the slippery slope we go.

Breaking our bad habit requires that we adopt a strict fossil-fuel-free diet. But we’ve reached a point where may also need some forms of climate engineering—limited and relatively benign—to restore stability to our climate and to reduce climate damage, especially in the most vulnerable regions. In our addiction to growth and fossil fuels we’ve wrought a vexing ethical tangle that will be difficult to sort through.

What is Climate Engineering?

Climate engineering, also known as geoengineering, is an umbrella term covering a broad set of technologies for avoiding dangerous levels of global heating. Analysts generally split the field into two families of technologies, each with a different approach to addressing warming.

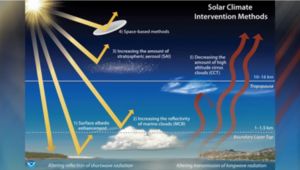

Solar radiation modification (SRM) is a strategy for deflecting away the sun’s rays to reduce the heating of our planet. Scientists imagine increasing the albedo (reflectivity) of the earth, say by covering glaciers in Antarctica with artificial snow or planting high-albedo varieties of barley, corn, wheat, or other crops. More exotic options include spraying reflective sulphates into the stratosphere or placing orbiting mirrors in space. Proponents of SRM note that most of the options are relatively inexpensive, at tens of billions of dollars per year for each degree C of cooling in the sulphate-spraying option. And it would provide quick relief from rising temperatures. Other advocates may see SRM as an easy way to skirt emissions reductions and to maintain economies run by fossil fuels. And SRM has serious downsides, described below.

Forms of Solar Radiation Management. (Chelsea Thompson, NOAA/CIRES)

Carbon dioxide removal (CDR) approaches would pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, thinning the blanket of heat-trapping CO2 molecules. CDR is a testament to the human imagination, featuring more than a dozen methods of removing excess carbon. Some are nature-based, like planting trees over massive areas. Others are mechanical, like direct air capture (DAC), which uses giant fan-like devices to draw air through adsorbent filters that isolate the CO2, concentrating it for sequestration. Still others alter marine ecosystems by encouraging the growth of carbon-rich plankton (for example, by scattering iron filings through the ocean). The plankton then sink to the ocean floor for a natural burial. All these CDR methods have drawbacks, whether ecological, political, financial, or ethical.

Which approach is best, SRM or CDR? In truth, the question is premature. Before considering any merits of climate engineering, we must tackle the little matter of emissions reductions. This is the elephant in the room in many climate engineering discussions.

The multiple technologies proposed for tinkering with the climate can easily dazzle us. But gee-whiz excitement may blind us to an important fact. None of these solutions addresses the core driver of the climate crisis, the emission of greenhouse gases. None is a complete solution to our climate challenge.

All climate engineering approaches are workarounds that sidestep dealing with emissions. Every one is a temptation to avoid the painful task of building new, carbon-neutral economies. Each makes at best an incomplete contribution to solving the climate crisis.

An honest, fully formed approach to climate policy requires that emissions reductions be not only present, but at the forefront. Climate engineering should play only a distant, secondary role. Even then, only the most benign, ecologically friendly options should be considered.

Fundamental Failure

Remember that geoengineering strategies would not even figure in the climate conversation if humanity had met its responsibility for emissions reductions decades ago. But we didn’t. Between 2000 and 2022, the world’s economies emitted enormous quantities of carbon, equal to 41 percent of the carbon emitted back to 1750. This growth-driven surge boosted concentrations of atmospheric carbon from 370 to 418 parts per million).

Carbon sequestration as nature intended. (Niko photos, Unsplash)

The surge has also tied our hands: Atmospheric concentrations are now so great that emissions reductions alone cannot provide for the 1.5-degree (Celsius) limit on temperature rise set in the 2015 Paris Agreement. Nor are they likely to keep us below 2.0 degrees of temperature increase. In fact, most IPCC scenarios for meeting temperature goals assume some use of CDR technologies to sequester carbon. And the U.S. government seems intent on exploring climate engineering, having provided billions of dollars in subsidies to help boost direct air capture technologies.

In fact, the longer serious mitigation efforts are delayed, the more the mercury rises and the greater the pressure to use climate engineering. More carbon indulgence coaxes us toward more extreme tinkering with Earth systems. Bad habits breed bad habits.

In sum, we err in framing climate engineering as a set of wonder technologies arriving just in time to save us. Instead, they are like crutches, temporary assists that support the hard work of rehabilitation. Our hard work, our rehabilitation of the climate, is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in a serious way.

What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

As helpful as some limited geoengineering practices may be, policymakers and the public must be clear-eyed about the risks involved. The list of risks is long. Here are just a few:

Rogue actors—What if a nation frustrated over feeble progress in cutting global emissions decided to take climate action into its own hands? It’s not as far-fetched as it may seem given the relative simplicity and affordability of sulphate spraying, at least for larger economies. Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future imagined just such a scenario, with India suffering mass deaths due to heat and responding by essentially skywriting with cannisters of sulphate. The government, perhaps understandably, frames an exotic and risky venture as necessary to protect its suffering people.

Long-term commitment—SRM in particular could introduce a major new risk. If nations start to reflect away solar rays without serious emissions reductions, they essentially commit to SRM indefinitely. Stopping the practice after a buildup of carbon would produce a spike in global temperature that many species likely could not adapt to. Who has confidence that nations would fund SRM solutions indefinitely to avoid such an outcome?

Would climate engineering be in the interest of this young African? (Seth Doyle, Unsplash)

Unintended consequences—Some measures to restrain global temperature increases could have detrimental effects at the regional or local levels. For example, some forms of solar engineering could cause changes in rainfall in parts of Africa or to the monsoon in India. What safeguards can we put in place to protect vulnerable regions? Are people in those regions part of decision-making on climate engineering?

Resource intensive—For CDR technologies, global-level interventions will require tremendous resources, both financial and physical. Even tree planting is no panacea. Planting 900 million hectares in trees would require the area of 2.74 Indias, raising questions about whose land would be used. Even then, the trees would remove around 8 billion tons of CO2 equivalent. This is just a fraction of the 52 billion tons of CO2 equivalent emitted each year. And young trees absorb far less carbon than mature trees, so the bulk of these gains would not be realized until the second half of the century.

Unproven—In 2023, a panel in the U.N. climate bureaucracy shocked the emerging CDR community when it declared carbon removal technologies “technologically and economically unproven, especially at scale.” It also said that carbon removal poses “unknown environmental and social risks.” Even Ocean Visions, which is bullish on marine-based methods of CDR, acknowledges that many are untried and have unknown effects. This, even as the global community needs climate action urgently.

Finding the Moral Middle

If we were tasked in 1990 to lay out an ethics of climate action, a single sentence would have sufficed. Cut greenhouse gas emissions as broadly and quickly as possible, starting with the biggest emitters. But economic growth and technological developments since 2000 have complicated the picture considerably and put us in an ethical bind. Navigating our choices requires ramping up our commitment to emissions reductions while carefully considering other actions that would keep temperature increases under two degrees.

On curbing emissions, we’ll need to be much less permissive than we’ve been in the past two decades. Electric vehicles, solar panels, and other “clean” technologies are part of this effort, but they carry their own moral hazard. It’s tempting to believe that adopting technological fixes is the extent of our responsibility. But we know that technological solutions alone often backfire and can produce more of the very harms we are trying to reduce.

A good effort in itself, but even a trillion trees wouldn’t finish the emissions-mopping job. (Eyoel Kahssey, Unsplash)

The most direct, broad-based, and cheapest way to cut emissions is to stop the economic growth that fuels it. Policy efforts focused here could yield substantial returns. Some of the draft bills from CASSE’s Steady State Economy Act project (such as the Mileage Fee Act, to be introduced next week) would be helpful steps in this direction.

With a serious commitment to emissions reduction, we can turn to mopping up as much excess greenhouse gases from the atmosphere as is safely possible. Climate engineering solutions should be those that mesh with ecological restoration, like tree planting, restoring wetlands, and designating “blue carbon” areas. The simultaneous contribution to biodiversity conservation makes such efforts a systems solution to the climate crisis. This stands in contrast to the single-issue, reductionist focus that characterizes many climate engineering approaches.

We got into the climate crisis by relying on tunnel-visioned engineering solutions. Let’s not double down on that mistake by tinkering with the climate. Greta Thunberg captures the idea: “A crisis created by lack of respect for nature will … not be solved by taking that lack of respect to the next level.”

Instead, let’s respect nature—and ourselves—and abandon the naïve notions of perpetual growth. We have the option of the steady state economy to fall back upon. It’s the adult thing to do.

Gary Gardner is Managing Editor at CASSE.

A lot of truth here, and it’s sobering.

All I can add is that it seems not unlikely that at some point in the future, with India spraying sulfate in the stratosphere in a desperate attempt to stop the 4th or 5th year of mass heat deaths, and Africa and China clashing over who gets to pull every single fish out of the sea .. the Overton window of public discourse is bound to shift, and people will say “holy hell, this can’t go on – what are we going to do?”

At that time I think Steady State Economics (and perhaps even CASSE) will get the spotlight turned upon it. When that happens, I am sure there will be a deluge of “what about” type questions. I’m cautiously optimistic that CASSE, and in particular the essays here on the Steady State Herald, will elicit responses like this:

“What about X? Huh? How does SSE deal with X?”

“Well, let’s see .. reading what these CASSE people have said .. hmm, actually, there is a policy answer on X and it sounds do-able.. ”

And so on and so on. Until we get to a point where people speak matter-of-factly about the transition to a steady state economy. It *might* get a different label, but I’m pretty sure we’ll see this transition in public discussion by 2050 at the latest. Hopefully much, much sooner!

Thanks, Cole. Yes, I agree that people will wake up as conditions on the ground change. It would be good to help move that waking process along so that the public discussion gets underway soon. We are still quite far from such discussion, outside of the choir. In this presidential election year in the U.S., not a peep out of the candidates regarding growth, except of course to continue to assert that more is better.

We will soon publish a letter from an NGO to the Canadian government that critiques Canada’s commitment to growth. It might inspire all of us to take steps (letters to the editor and to legislators, questions to candidates, and the like) to move along the waking process. Stay tuned. And thanks for your comment, Cole!

Good vision Cole. Entirely conceivable.

Herman Daly and I got an early start preparing for such a day with an article, “The Steady State Economy: What It Is, Entails, and Connotes” (https://steadystate.org/wp-content/uploads/Steady-State-Economy-What-it-Is-Entails-and-Connotes.pdf ). It was published in the trade journal of the wildlife profession, titled at the time “Wildlife Society Bulletin” (now “The Wildlife Professional”). The Wildlife Society was in the midst of controversy on whether to adopt a position on economic growth, mirroring the CASSE position, so we felt a need to elaborate on the steady-state vision in that particular venue.

These years later, I’m less sanguine (like you, it sounds) about the prospects for a democratically functional transition straight away to a steady state economy, in the USA especially. We’ll be caught way behind the 8-ball and there will be a dire need for “degrowth toward a steady state economy.” And actually, by then, the degrowth phase won’t be optional; it will have begun.

And then yes I hope the majority will be looking for steady-state answers, more so than guns. But I suspect this choice itself is becoming a barrier to action: People see the future as potentially or even probably so dire and prone to violence that they just start shutting down or going into denial.

So, for CASSE and the like, it’s quite an understatement to say: Time is of the essence.

Thank you Brian – I definitely cycle through periods of cynicism as I regard the world around us. I think the most objective thing I can say is that humans seem incredibly stuck in their ways until there is a crisis.

I can’t think of exactly the right analogy, but if it takes a crisis, I think CASSE will be a lot like a cardiologist or endocrinologist when a person has a heart attack or is diagnosed with diabetes. Suddenly the person with expertise and answers has the patient’s full attention! I hope things don’t unfold like that, but if it does, having the answers ready will be the best work we can do (my opinion).

More hopefully I’m impressed by how younger generations, such as my daughter and her friends, seem absolutely ready to transition to a steady state type of world.

Cole succinctly describes the multi-polar trap, ie. tragedy of the commons, in his sentence about China and Africa vying to pull the last fish from the sea. This mirrors the tragedy of the commons that prevents any nation from adopting a steady state policy unless other nations do likewise. Growth is necessary to fuel a military, and any slack in that invites attack. Look at the Russian attacks on Ukraine, since the latter voluntarily renounced its nuclear arsenal.

On the other hand, if they can stave off attack, the country that adopts a steady state policy gets the last laugh, as they will be the last place with remaining oil reserves when others have sunk their own economies by depletion.

Meanwhile, India is already performing SRM by doubling down on coal. Vandana Shiva must be livid.

For what it’s worth, I’m slowly working out a potential article for the Herald here on exactly how a society could at least begin a transition to a steady state economy, while also transitioning the military, without being “suckers” and making themselves open to attack by the Putins of the world. I’ll try to be reflective and acknowledge that the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 surely would look to an alien from another planet as basically the same behavior as the invasion of Ukraine. No society seems immune to bad behavior by its elites.. alas.

There are some knotty issues involved in such a transition that I’m still banging my head on. In the long run I think militaries per se are not compatible with a steady state economy, *but* I think they can be transitioned, over time, to what one might call emergency response forces. I’m pretty sure that even in a world of peaceful societies, in a steady state, there will be no shortage of natural disasters and other crises that need a response requiring many of the same attributes that military forces have today.

Anyway, more to come, if I can figure it out to my satisfaction (and to the satisfaction of the Herald’s editors). For context I was in the US Army a long time ago as an officer in a tank battalion, so I’m pretty familiar with many of the dynamics involved. A transition of the military and the military-industrial complex seems very daunting, but I think it can be done.

For me, it may go one of three ways one; continue towards an unsavoury violent death scramble for increasingly scarce resources.. two A French revolution style uprising of the have nots, followed by Robin Hood type gang leadership emerging from the anarchy as seen in Haiti, with maybe an equitable sustainable society evolving from the chaos. Or three my prefeence for a cultural shift towards taking our individual responsibility to shift our demand to the not for profit not for growth suppliers. Tech can encouage viral behavioural change when individual ethical consumer reputations are shared. Ethical suppliers can exponentially grow as amazon has done. Surpluses can be directed at levelling up disadvantaged lives and building cooperation towards working peacefully together to protect sustainable well lived lives.

I’m definitely with you in hoping for option #3. I wonder if we might see all three scenarios play out in different areas? Sigh.. the future is probably going to be weird and unexpected. On the other hand, sometimes there are good surprises as well.

I agree with Conor’s cultural shift, and would add that the health of individuals on the earth is directly related to the health of the earth, so that not-for-growth and not-for-profit suppliers would also supply less to a population that needs and wants less. A large part of the growth economy is spent with “tunnel-visioned engineering solutions” that make us lazy spectators, when in fact, the only renewable energy is our own human-metabolic energy. Our lack of respect for nature (Gary quotes Greta on this) is also a lack of respect for our human metabolic nature.