Debt, Deficits, and Warranted Money

by Brian Czech

Concern over mushrooming debt is growing. Click on the image to see the casino-like tumbling of national debt “clocks.” (US Debt Clock)

If you recognize the damages done by a bloating economy, you’ll be alarmed by the global GDP meter, which hit the existentially menacing threshold of $100 trillion in 2022. If that doesn’t give you a dose of distress, try the global debt clock. Then, for a dizzying dose indeed, check the casino-like combination of debt and GDP maintained by “US Debt Clock.”

Almost all readers, bearish and bullish alike, can sense the unsustainability of skyrocketing debt. Even wild-eyed growthists, who see no problem in a perpetually growing GDP, can’t abide a perpetually growing debt. Yet very few critics of debt can articulate, with economic fundamentals, why such debt is so unsustainable.

Sadly absent from the discussion of debt is the ecological underpinnings of money. As long as these underpinnings remain overlooked, the money lenders will be overbooked. Deficit spending will rule the day, and global debt will continue rocketing into the stratosphere, heading for the sun like a pecuniary phoenix.

Let’s have a closer look at the debt problem, with a focus on global and U.S. scenarios. We’ll consider the relationship of debt to deficit spending, along with inflation. Finally, we’ll bring in the ecological basis of money, and hope our policymakers grasp and apply it, lest our money supply—not to mention the planet—turn to ashes.

Deficits and Debt: Global and U.S.

As global GDP was ramping up to the planetarily punishing $100 trillion level, global debt was already surpassing $300 trillion. It reached that dubious distinction in 2021, just one year after reaching the previous record of $226 trillion. It has since come down from the peak, but still stands around $238 billion, and the reduction is surely short-lived.

The majority of global debt is private, especially corporate but significantly household debt as well. Public debt—money owed by governments—makes up about a third.

In the USA, those proportions are roughly reversed. From the county commission to Capitol Hill, American politicians have ambitions that far exceed government coffers. When they’re not spending money to “stimulate the economy,” they’re trying to spend their way out of the social and environmental problems caused by an overstimulated economy. They spend money they don’t have; that’s deficit spending and it adds to the public debt.

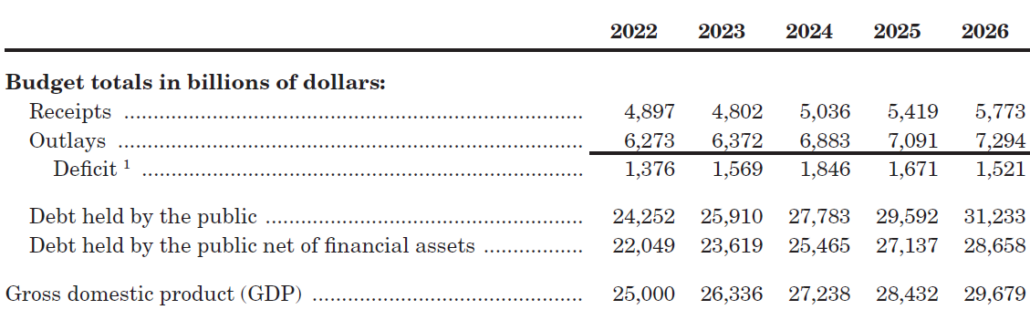

Deficit spending is a way of political life in the U.S. Government. (Image snipped from 2024 Budget of the U.S. Government.)

At this point in fiscal year 2024 (October 1, 2023 through September 30, 2024), the U.S. government deficit stands at roughly $532 billion, contributing another two percent to the federal debt of $26 trillion. The deficit may lessen as taxes are collected in the coming months, but then it will shoot back up for the remainder of the year. Even the figures provided by the Administration (probably rosy figures) acknowledge that the deficit is expected to be a whopping $1.8 trillion by the end of fiscal 2024. That’s nearly seven percent of the 2023 GDP.

The USA is particularly relevant to the global debt; its debt is bigger than any other. In fact, U.S. entities—government and private combined—carry a debt burden nearly the size of the global economy!

Only Japan and China have joined the USA in the club of over $10 trillion government debt. France, Italy, the UK, Germany, India, Canada, Spain, and Brazil all have debts exceeding a trillion dollars.

In terms of relative debt (ratio of debt to GDP), Japan is at the top of the list at 255 percent. Greece, Singapore, Italy, Bhutan, and the USA (123 percent) round out the top six.

Deficit Spending: Getting Dumb and Dumber?

Deficit spending has a long history in American policy. The fiscal exigencies of war have triggered deep deficits, with World War II as the classic case. But huge deficits were already incurred during the Great Depression, coinciding with the influence of the British economist John Maynard Keynes. In the General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, Keynes prescribed a liberal dose of deficit spending to spur the western economies out of recession.

But Keynes never said to go hog wild, much less stay that way. So, for many decades now Americans have heard the debate between fiscal conservatives and “deficit-spending liberals.” They both want growth, but conservatives think a persistent deficit and ballooning debt is more burden than boon for GDP. They typically only abide a big debt for hawkish military purposes. Otherwise they’re “budget hawks.”

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, are you sure about MMT? (Wikipedia)

Inveterate deficit spenders, on the other hand, think they can stimulate the economy by picking the winners and funding the right programs.

Into this old debate comes “modern monetary theory,” centered around the idea that deficit spending is generally fine, and policymakers needn’t worry too much about a growing debt, as long as the economy is also growing. Beyond that, “MMT” seems to mean many things to many people and has polarized the economics community. Even pollyannish growthists like Paul Krugman find MMT “obviously indefensible.” Another growthist (aren’t they all?) at the dark-monied Mercatus Center calls MMT “a bizarre, illogical, convoluted way of thinking.”

MMT does, however, provide some political cover for politicians hunting pork. The late King of Pork, Senator Robert Byrd, would have championed MMT all the way to the bottom line. But MMT has persuaded some presumably more fiscally innocent members of Congress, most notably Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Senator Bernie Sanders, and even John Yarmuth, past chair of the House Budget Committee.

In any event, it’s hard to tell what’s so “modern” about MMT. It has a few new wrinkles—it picks them up as it goes along—but basically it’s just another phase of Keynesian thought on deficit spending. And, as President Nixon said a half century ago, “We’re all Keynesians now.” He could have added, “We’re all growthists, too!”

And so, the first subheading that appears in this year’s federal budget (page 5) is: “GROWING THE ECONOMY FROM THE BOTTOM UP AND MIDDLE OUT.” We could add: “WITH A SHOT OF DEFICIT STEROIDS.”

Money Supplies: Warranted vs. Inflated

In 1939, one Sir Roy Forbes Harrod wrote “An Essay in Dynamic Theory,” published in the stately Economic Journal. Until then, little had been theorized about the process of economic growth, and rarely with such nuance. Harrod’s approach is considered a leading precedent of growth theory.

Harrod spent much of his 20-page essay contemplating three kinds of growth rates: warranted, natural, and actual. Our charge here is not to dive deeply into Harrod’s thoughts on growth rates, but to see where they take us on debt and inflation. In particular, I propose we have three levels of money supply: warranted, real, and nominal.

Economists are familiar with the latter two. The real money supply has been adjusted for inflation, typically by pegging to a particular year. The nominal supply is expressed in terms of face value in real time. For example, $1.38 trillion today—the nominal money supply of a hypothetical country—is only one trillion real dollars, if we’re pegging to 2010.

It’s the “warranted” supply I’m proposing here. The concept stems from the trophic theory of money, which is that money originates via the agricultural surplus at the base of the economy. Not agricultural surplus in the sense of grain going to waste in the fields, but surplus in the sense that one farmer can grow enough to feed many people.

It is that surplus—more broadly, a food surplus but for all practical purposes the agricultural surplus—that frees the hands for the division of labor. The division of labor, in turn, allows for the exchanging of goods and services. All this calls for an efficient means of exchange, store of value, and unit of account: money, in other words.

Money is warranted, then, by the division of labor flowing from agricultural surplus.

Money didn’t just originate historically via agricultural surplus—as it did in Mesopotamia, Lydia, and the Yellow River Basin of China—it originates each year in the breadbaskets of the world. Actually it originates twice a year as these breadbaskets are found in Northern and Southern Hemispheres. North America (prairies and California), China, Southeast Asia, Brazil, and Chile come to mind, plus of course the contested confluence of political Europe and Russia, centered in Ukraine.

You might say money gets “printed” into circulation with each perennial pulse of wheat, rice, corn, oats, barley, and soybeans. Massive harvests free billions of hands for a spectacular division of labor and the exchanging of trillions of dollars of warranted money. Lenin was right on the money (so to speak) when he referred to grain as “the currency of currencies.”

Wheat combine “printing money” in North Dakota. (Flickr)

Think about it: How would money remain relevant in a world of agricultural collapse? Everyone would be occupied with growing, gathering, catching, or commandeering their own food. No one would be producing other types of goods and services, much less bringing them to market. Money would be worthless; it wouldn’t be warranted.

Not so with the collapse of massage services, NASCAR, hip hop, or even Taylor Swift. Nor with the disappearance of boats, guns, electronics, fur coats, or perfumes. A thousand container ships of manufactured dreck could be dumped in the Panama Canal, never to be seen or sold again, and the economy would persist. Plenty of other goods and services would remain. Money would still be meaningful, relevant, and valuable.

It’s an entirely different story with the world’s soy, root crops, poultry, livestock, finfish, and, above all, grain. Burn those up like some omnipotent, omnipresent Putin, and watch the economy come tumbling down in days.

That is why, in a fundamental sense, it is agricultural surplus that “prints” money into circulation. The warranted money supply, then, is that which reflects the amount of agricultural surplus. Lots of surplus warrants lots of money; little surplus warrants little money.

The trophic theory of money doesn’t explain every possible aspect of monetary economics, at least not directly. For example, how big a role do livestock and fish play in food surplus and therefore warranted money? What’s the linkage of food surplus to energy inputs? What about other natural resources at the trophic base of the economy such as heavy fiber and timber? (It takes clothing and shelter to subsist, not just food.)

The trophic theory of money generates plenty of research questions, but it provides plenty of insight as is. Take inflation, for example. That’s when the nominal money supply exceeds the warranted supply.

Limits to Warranted Money

While it is helpful to think of money as being “printed” into circulation with agricultural surplus, it is even more helpful to think of money being “footprinted” into circulation. There’s no way to produce an agricultural surplus—or a warranted money supply—without a heavy ecological footprint. Not for a population of eight billion people.

It takes a lot of inputs to grow a lot of food, so the ecological footprint of agriculture reaches far beyond the field. (Flickr)

Each parcel on the planet has a biological capacity. So, given limits to agricultural efficiency, we know that the ecological footprint of agriculture can only reach so far (or sink so deep, if you prefer). Then it exceeds the biological capacity, agricultural surplus plunges, and the warranted money supply drops like a shot.

The pre-existing, nominal money supply remains, but to what avail? With no agricultural surplus, businesses big and small disappear—banks, too—and the government defaults. All but the most civilized (or uncivilized but ethical?) polities descend into some sort of chaos. The nominal money supply might still be in the trillions of dollars, but it’s neither warranted nor real. It’s like the gold supply of King Midas. It’s hyperinflated, not because of an “overheated” economy and the pull of demand; quite the opposite. It’s devalued by “cost-push” inflation, the relentless price increases due to diminished stocks of natural capital.

What the Fed Needs Now

The Federal Reserve, U.S. Treasury, Budget Committee(s), World Bank, and all the other fiscal, monetary, and financial institutions need a reality check in the form of basic and applied ecology. They need to learn especially about the concepts of trophic levels and carrying capacity. Otherwise they won’t be able to sufficiently connect the dots among deficits, debt, and cost-push inflation.

Right now, the Fed’s approach to curbing inflation is the ham-handed raising of interest rates. But raising interest rates only works (sometimes) for the “demand-pull” form of inflation, where prices rise due to an increasing propensity to consume, or due to an injection of nominal money (as with deficit spending). It’s no remedy for cost-push inflation stemming from limits to growth in the real economy.

The Federal Reserve needs ecological training to manage inflation. (Wikipedia)

I’m not saying these accomplished folks—geniuses in other ways—have no sense of economic capacity. They most certainly do; they monitor and talk about it all the time. Unfortunately, they have essentially no knowledge of ecological capacity, so their notions of economic capacity are flawed. They tend to think of capacity in terms of financial capital, labor, manufacturing facilities, infrastructure, and new technology. It’s reminiscent of Herman Daly’s lament about focusing on the kitchen and the cook, with little thought to the ingredients.

When is the last time you heard a Jerome Powell or a Janet Yellen utter a word like “soil” or “water” or “forest” or “fishery”? Yet those are the stocks of natural capital at the very base—the trophic base—of the economy they preside over. They should be intent upon conserving those stocks, if not for purposes of long-term human wellbeing (which would be nice), then at least for purposes of fighting inflation!

Brian Czech is CASSE’s Executive Director.

Interesting theory. However, it pays no attention to the actual process of the creation of money, which has nothing to do with agricultural harvests. Perhaps this does not undermine the notion of “warranted money” but two points: firstly, if there is no relationship between warranted and real money, what is the relevance of the former? I doubt you can explain inflation / deflation dynamics with reference to agricultural surplus, but if you can this would be an amazing result. So please show us the stats supporting this theory. Secondly the logic points to division of labour rather than agricultural surplus per se. In an economy consisting only of substance farmers there would still be a division of labour and reason to trade since people can’t survive eating just one food commodity. And so there would still be a need for means of payment and therefore money. Finally you don’t say what is wrong with MMT exactly, apart from the fact that it;s a misnomer. Fine, call it not-so modern monetary theory – what’s wrong with what it says about money creation and circulation?

A lot of food for thought here (no pun intended). I like that you give credit to Fed policymakers and others as “geniuses in other ways.” A pattern I’ve seen over and over is that many decision-makers are in fact pretty capable – they’re not dummies – but they are terribly overburdened and have to deal with huge amounts of context switching.

One thing that might help is a strategy recommended by a fellow Douglas W. Hubbard, who runs a consulting business that deals with quantifying risk (I took part in a workshop of his). For a given policy idea, however sound one thinks it is, one should go through the exercise of writing down a few sentences from an imaginary future pundit or analyst describing *why the policy failed despite great expectations.*

That sounds odd but I’ve found it strangely useful. Basically one looks at one’s freshly hatched, best ever idea, and says “well, this is silly, but if it were to fail for any reason it might be.. X, or Y, or a combination of X and Y.” And bingo, therein lies some new insight. I’ve found that fairly often one concludes that one’s beautiful new idea is in fact more than a little vulnerable to flaws X and Y.

For members of the Fed and others, maybe this exercise of “how will this fail 10 years from now” could yield new insights that they badly need. Maybe I’ll write them a letter to that effect, I’ll at least feel as if I’ve done something.

The route to sustainability through chaos maybe anarchy is not an appealing one. Brian, a read well worth working through. Policy makers can keep inflation in check only while we have sufficient life supporting resources available. As we hit this threshold chaos may ensue, currencies and central banks may collapse, currency holders may panic as weak economies tank, switching to bitcoin etc. These currencies uncontrolled by central Bank interest rates may further fuel inflation and the economic tailspin.

You are correct with the trophic theory.

Let’s not do this chaos; support Not for profit suppliers, if you have to buy a coat buy a Patagonia coat and make it your last coat purchase etc.