Economic Growth Takes a Bite out of Fishing

by Stephen Coghlan

“A bad day fishing is better than a good day at work,” proclaimeth bumper stickers throughout my neck of the woods in central Maine. No disagreement here! For humans, fishing is fun and mentally and physically stimulating. Fishing also engenders respect for nature, relieves stress, and sometimes provides a tasty meal; though not so much for the fish.

Hardly a lunker, but “a bad day fishing is better than a good day at work.”

Fishing is deeply embedded in American culture, in part due to public-trust doctrine of wildlife management, legacy of subsistence fishing by poor rural folk, and postwar economic growth and widespread affluence allowing suburbanites and city-slickers the means to enjoy nature. But that economic growth has degraded and threatens to destroy many freshwater fish and recreational fishing opportunities for current and future generations.

Freshwater fish are some of the most imperiled biota in the world. Threats vary by species and location, act synergistically, operate through many pathways, and include overfishing, deforestation, pollution, damming, irrigation, exotic species, habitat loss, and climate heating. But all of these are merely symptoms of the ultimate cause: overshoot.

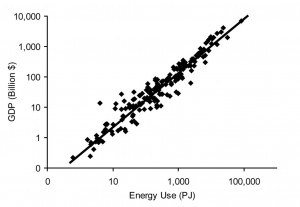

Empowered by fossil energy, lubricated by debt-based money, and justified by faith-based economics, the human ecological footprint has grown beyond planetary carrying capacity; we’re depleting resources faster than can be replenished, producing waste faster than can be assimilated, and destroying biodiversity faster than it can evolve. The global economy acts as a mindless, self-organizing, energy-hungry amoeba designed to grow, incapable of recognizing any limits. We’re incessantly turning nature into more of us, our things, and our effluents, leaving less nature for future generations and other species.

Ramblings of a Middle-Aged Fish-Squeezer

Most of my adult life has revolved around studying and catching freshwater fish, but I didn’t grow up in a “fishing family.” My maternal grandfather grew up dirt-poor on a farm in Central New York during the Great Depression and did his share of sustenance fishing and hunting. This was about 40 years after the worlds’ largest population of landlocked Atlantic Salmon was driven to extinction in his backyard and Onondaga Lake was well on its way to becoming the most polluted lake in North America, but about 30 years before PCB contamination made fish in Skaneateles Creek unsafe to eat for generations. Grandpa sat me in his lap and read from Field and Stream and taught me about local fish and wildlife, recounting stories of monster brown trout in North Brook. Fascinating, but I was content with armchair natural history.

Onondaga Lake in New York State: a place to fish, if not healthily. (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, NYS DEC)

My father wasn’t outdoorsy, but he enjoyed rural Cape Cod in the early 1960s (before urban sprawl and tourism chewed up forests, fields, marshes, and beaches), when alewife ran so thick he could catch a mess in an old hubcap. When I was about five, Dad took me fishing twice, once at Owasco Lake (long before septic tank runoff and toxic algae closed beaches) and once in Crane Brook behind the brand-new Finger Lakes Mall (which sparked more sprawl into surrounding countryside, destroyed local businesses, and now is a ghost town anchored by a fizzling Bass Pro). Catching rock bass on worm-and-bobber was fun, but Star Wars was more interesting.

Later, a family friend introduced me to angling for lake-run rainbow trout and dip netting for rainbow smelt. Back then, “No Trespassing” signs were scarce, April 1st was cold and snowy, and a piece of orange sponge soaked in tuna oil was magic. Tiny streams literally “ran black” with smelt and you could catch your limit five-gallon-bucketful in a few minutes.

Something stirred within me. I bought a cheap rod, practiced my casting, tied crude flies with fur from my Shepard-Husky mix, Sam, and bided my time until I could drive. I spent many mornings on Dutch Hollow Creek as the bus delivered kids to high school without me. I sought help from a local fly shop (eventually driven under by Bass Pro) and the owner, Mike, was patient and generous. I fished hard but rarely caught, and wondered if trout even existed. Mike assured me they did; he had pictures to prove it.

One gorgeous fall day, I happened upon a spawning pod of lake-run brown trout in Mill Creek and watched with fascination as males fought, females dug, jaws gaped, bodies quivered, and gametes spilled. I had an epiphany, knowing I must spend my life studying these creatures and eventually catch some. College friends and professors helped immensely. Twenty years later I’ve caught a few fish and squeezed a few more, but the more I learn and experience, the less confident I am that recreational fishing has much of a future.

Economic Growth: No More Fish Stories

Recall those fish-threatening “proximate causes” that arise from economic growth. Many of these threats contribute to economic growth: clearcutting a watershed for lumber, damming rivers to generate hydroelectricity, dumping toxins in rivers to increase profits. Let’s consider some of the biological and ecological impacts, using examples from New York and northern New England, my home range as ecologist and angler. We’ll focus on a few popular “sport fishes” that I happen to value: salmonines (the salmonids comprising trout, salmon, and char) and panfish (sunfish, bass, perch, etc.). I do, however, realize that this distinction of “value” is laden with Euro-centric cultural biases; so, apologies to my Indigenous friends.

Atlantic Salmon cannot tolerate a large and expanding human footprint, and most salmonines are just as sensitive. Sea-run and landlocked Salmon were native to Northeastern USA before European invasion, as were brook trout, lake trout, and Arctic chars. Rainbow and brown trout were and are introduced widely, and some have become naturalized. Hatchery and naturalized coho and chinook salmon exist in Lake Ontario. We can generalize that most or all salmonids are intolerant of heat, low oxygen, and toxins. They also require clean, cold water, express complex life-histories, and need access to diverse habitats. Lastly, they evolved in forested watersheds with seasonally-reliable temperature and flow regimes.

Links between economic growth and salmonine declines are clear. Sea-run Atlantic salmon once swam up the Penobscot River in hundreds of thousands (and in other coastal rivers from Connecticut to Russia), along with millions of river herrings. A nascent industrial economy grew by building dams that blocked migration to spawning grounds, deforesting huge swaths of Great North Woods, destroying stream channels with log drives, poisoning rivers with toxic effluents, overfishing for profit, and ultimately killing more salmon than could be sustained.

A spent salmon in waters warmed by a bloated GDP. (CC BY 2.0, Robert Couse-Baker)

Eventually, the Clean Water Act and others helped buffer the Penobscot from the worst insults and improved water quality, but salmon kept declining. Hatcheries and the Endangered Species Act have postponed extinction, and the Penobscot River Restoration Project has removed dams and improved habitat. River herring runs seem to be recovering, and this could benefit Atlantic salmon by fertilizing streams and providing cover from predators. But climate catastrophe (itself a consequence of economic growth) is almost certainly the last nail in the salmon’s coffin.

Across Maine (and almost everywhere), quickly heating rivers and more extreme droughts and floods are leaving less habitat suitable for survival, growth, and reproduction. Invasive and heat-tolerant smallmouth bass have spread throughout most watersheds, and are dangerous predators and competitors of salmon. Climate-driven shifts in ocean food webs, along with loss of genetic diversity, skews spawning runs towards smaller and less fecund fish.

Similar stories exist for other salmonines. Landlocked salmon were driven to extinction in Lake Ontario and Finger Lakes watersheds by damming, deforestation, overfishing, pollution, and exotic species introduction. Brook trout have declined or been extirpated across their native range, with few strongholds limited to high-elevation, sparsely-populated watersheds from Adirondacks to Aroostook—again, for similar reasons.

Short-lived, slow-growing brookies are vulnerable to overfishing and require strict limits on harvest; most populations are sustained by stocking. Unfortunately, anglers tend to target and remove the largest fish, leading to “unnatural selection.” Although rainbows and browns are nonnative, and may outcompete native salmonines, they have similar niches and responses to stressors. Spawning streams in the Finger Lakes suffer more extreme heat, floods, and droughts, especially in deforested watersheds, so fewer wild fish exist and more stocking is required to support angler demand.

Of course, some examples exist of where local economic growth has benefitted local salmonids. For example, hydroelectric dams in the Delaware watersheds created deep reservoirs, cold tailwaters, and thermal refuge for browns and rainbows.

Hooked on Growth

Economic growth also threatens fishing. Motivation and skill vary among anglers, but I’d say most people prefer to catch more and larger fish in more pleasant settings. (Anglers desire remote but easily accessible areas—don’t we all!) It follows that fewer, smaller, harder-to-catch fish in fewer, more crowded, uglier places diminishes the fishing experience.)

Although the number of licensed anglers has decreased significantly, it’s unclear whether overall fishing activity has declined. It might have (due largely to poorer fishing), but sometimes it feels like the fishing pressure has simply become more concentrated. The old saying goes that 10 percent of anglers catch 90 percent of the fish. That 10 percent can be awfully stubborn, and for the rest, remember the motto, “A bad day fishing is better than a good day at work.”

They managed to find a fishing hole. Will they find their way to the town hall to object to the county’s growth plan? (Shutterstock)

Heavy stocking masks the collapse of wild fisheries and attracts anglers who otherwise might not fish. Legal protections from ESA prohibit recreational angling, like for Maine Atlantic salmon. And the ultimate economic insult is fish so contaminated with mercury or PFAS that they shouldn’t be consumed.

Catchability varies among individual trout. Some are prone to capture and removal quickly, leaving frustratingly difficult fish. Naïve trout are caught-and-released easily once but learn quickly to reject flies and hide from anglers; experienced trout acclimate to anglers but remain skeptical of flies.

Increased crowding makes fishing more challenging, exemplified by Magalloway River in northwestern Maine, known for large wild brook trout and heavy pressure, concentrated in a short stretch of tailwater that increases over summer as nearby rivers heat. Catch-and-release ensures that some fish are caught repeatedly, and none are (legally) removed.

These trout tax my patience and skill, yet the occasional reward (including a five-pounder caught before sunrise on the summer solstice) outweighs the long drive and increasingly crowded streambanks. But for how much longer? As global heating proceeds, anglers must travel farther to catch salmonids (burning more fuel and emitting more CO2 in the process), if not discouraged by high gasoline prices or disrupted by energy-economic shocks.

Shorter winters and thinner, less dependable ice cover also threaten ice fishing. Many salmonine fisheries are closed or tightly regulated then and impossible to access without snowmobiles. Enter panfish. Panfish generally tolerate more human disturbance and are found closer to population centers, but this means easier access and crowds.

Pumpkinseeds are highly desirable and fished hard in New York, but nearly ignored in Maine. Small, sheltered ponds freeze quickly and provide excellent early-season fishing but may suffer from anoxia later on, especially in agricultural watersheds. Black crappie are slowly invading northeastwards, and newly established populations seem to provide about a decade of spectacular harvests before intraspecific competition kicks in and word spreads among anglers.

Prolonged heavy fishing eliminates largest and oldest fish, leaving many runts. I’ve been testing my pet hypothesis that sustenance ice-fishing for panfish is a smart investment in self-reliance to buffer against economic and ecological shocks from overshoot. One skilled angler can harvest lots of biomass, but every calorie of fillet demands at least 50 calories of mostly fossil energy—worse than industrial agriculture!—and only so many anglers could attempt this before fisheries collapse. Nevertheless, ice fishing will soon be just a fond memory.

Speaking Trout to Power

Town hall meeting. Notice the incongruent slide: “Improving life on earth and protecting our planet…Strengthening U.S. economy through science and technology.” Anglers in the audience should be ready to rectify. (CC BY 2.0, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center)

Old-timers have always lamented “fishing ain’t what it used to be,” but hardly anybody blames economic growth directly. Aside from a few of my like-minded fishing buddies and students, most anglers and biologists I encounter fail to see the connection. Anglers who grumble that northern Maine is turning into Massachusetts see the trees but miss the forest when in the next breath they argue that rural communities need economic growth. After all, what else could possibly convert the Great North Woods into the Bay State but economic growth?

Many die-hard anglers resist acknowledging the climate emergency, even though objective data and lived experiences say otherwise. Central New York fishing guru and local icon Mike Kelly advocates passionately for protecting trout and streams from direct human insults (he’s seen them all in 60+ years of fishing), but devotes one dismissive sentence to global heating: “Since Central New York residents were just digging out from one of the coldest winters in the last half-century…I’m not quite ready to concede that we are seeing the results of ‘global warming.’” I wonder if the last eight years of record-breaking heat have changed his mind.

Even my own university, that prides itself on “sustainability” and expertise in fish and wildlife management, seems to justify its existence on grounds of promoting economic growth. However, a very near-exception to this rule is Trout Unlimited. TU is extremely proactive in identifying proximate threats to cold-water fish and fishing, and is actually achieving results through lobbying, public education and engagement, and on-the-ground conservation and restoration. At times they come tantalizingly close but stop just short of admitting that a growing economy is incompatible with their mission. Maybe they need just a little nudge from us steady staters, and others will follow. Fish need breathing room too.

Stephen Coghlan is CASSE’s Maine chapter director and an associate professor of freshwater fisheries ecology at the University of Maine.

Stephen Coghlan is CASSE’s Maine chapter director and an associate professor of freshwater fisheries ecology at the University of Maine.

Excellent article Steve. It makes so much common sense, and resonates thoroughly with me as a biologist and as a fisherman.

In my opinion the fisheries profession suffered its greatest embarrassment since Spencer F. Baird brought carp to North America (1860s!) when the American Fisheries Society failed to adopt the position on economic growth brought before it in 2005. The AFS had a perfect opportunity to join the likes of the U.S. Society for Ecological Economics, The Wildlife Society, American Society of Mammalogists, Society for Conservation Biology and other scientific, professional societies in explicating the fundamental conflict between economic growth and environmental protection (specifically fish conservation in the case of AFS). They only missed it by one vote, but that’s no cigar.

Maybe your article will re-awaken at AFS a sense of responsibility for refuting the fallacious rhetoric that “there is no conflict between growing the economy and protecting the environment.” I hope it also lights a fire under some of the NWF chapters, fishing clubs, Izaak Walton League and the like to start addressing the topic of economic growth, the ultimate limiting factor for fish conservation.

All I can add is that the need to satisfy economic growth’s endless thirst for resources is seeing the twilight of salmon runs in Northern California. The water that would have run to the sea is being diverted more and more, so, naturally, the salmon are simply running out of viable cold water rivers to return to. Sigh.

Great article. Re-blogged on Lowimpact – https://www.lowimpact.org/posts/how-perpetual-gdp-growth-is-killing-fishing

We at Lowimpact applaud your efforts to educate people about the connection between GDP growth and environmental damage. We provide ways for people to reduce their impact on the natural world, but individual actions are not enough, in a system dedicated to perpetual growth. It’s the most obvious, yet bizarrely, least understood aspect of the tragedy that’s headed humanity’s way.