Elk County: A Story of Restoration and Recapitulation

[This is an edited version of the article that first appeared on January 23, 2026. It has been edited for geographic accuracy in the first two paragraphs.]

by Dave Rollo

Pennsylvania is known for its public lands and forests. Beautiful Elk County, Pennsylvania, is no exception. It boasts rugged, forested scenery with rolling hills, deep valleys, numerous streams, and vast woodlands. Part of the Pennsylvania Wilds, the county is spotted with mostly rural settlements.

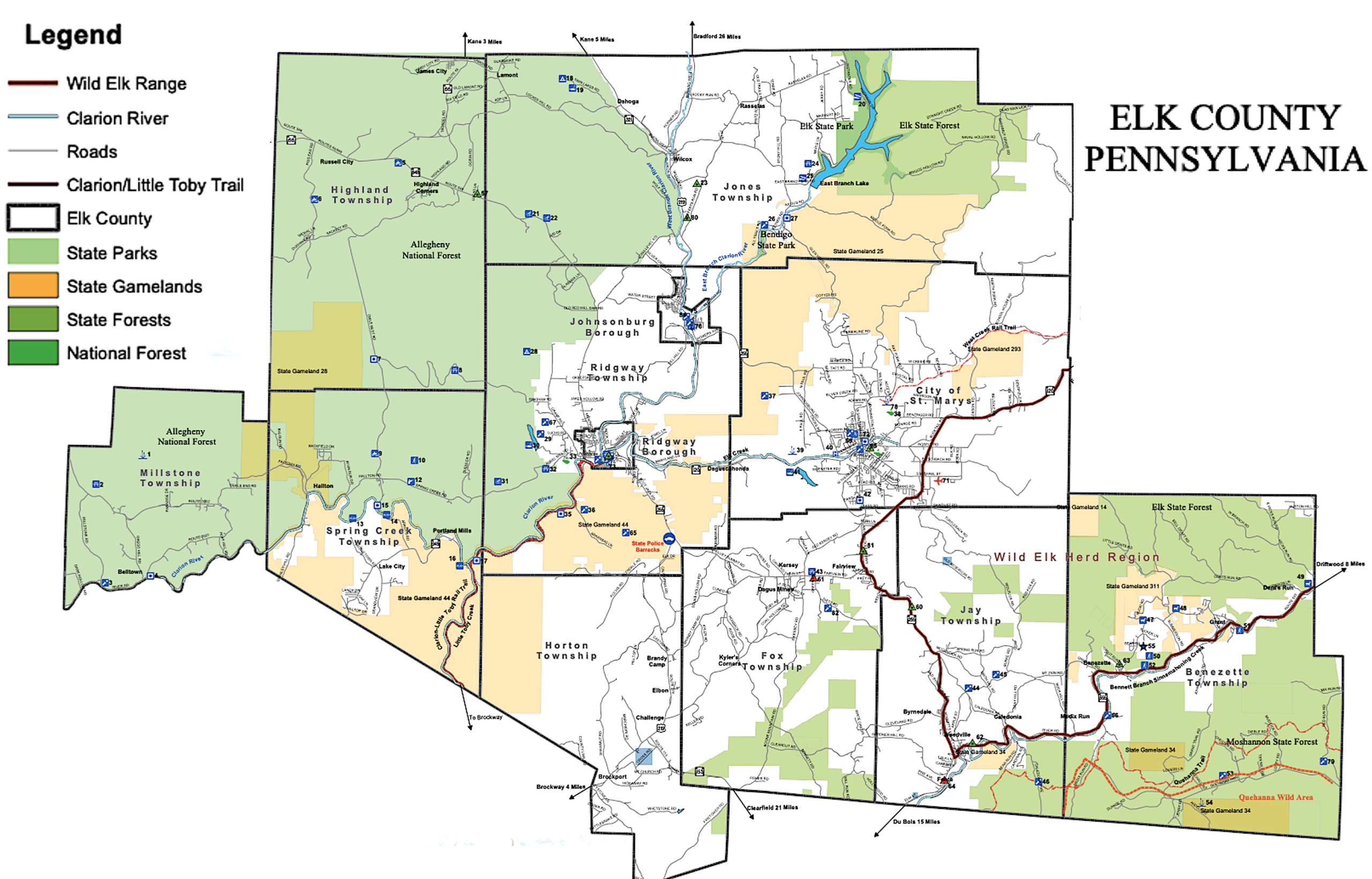

Elk County, Pennsylvania, has abundant forested land—the majority of it public. (Elk County, Public Domain)

Although the Pennsylvania Wilds comprise about a quarter of the state’s area, only four percent of Pennsylvanians reside there. Approximately two million acres of the Wilds is public land, as is about half of Elk County. The Allegheny National Forest covers the majority of the county.

Elk County is consistently ranked within the top five most forested counties in the state, but a century ago, it was a different matter. A boom in settlement and industry in the 19th and early 20th centuries left nearly all of Pennsylvania clear-cut. The prominent historian and conservationist Henry W. Shoemaker referred to the region as the “Pennsylvania Desert.” Lumber was used for construction, but much of the forest was turned into charcoal and coke—fuel for metal smelting.

Mining for metals and coal exacerbated the ecological destruction with tailings that acidified the silt-choked streams. Biodiversity plummeted, leading to the extirpation of many species. Unregulated timber and other extractive industries made quick profits, then moved westward, leaving an impoverished wasteland in their wake. State and federal government stepped in, launching a massive tree-planting effort to prevent a catastrophic loss of topsoil.

A century later, Elk County is heavily forested. Appearances can be deceiving, however. The tree composition has changed, large predators are still absent, and surface-water monitoring reveals a legacy of soil contamination still impairing streams. These are reminders of the lessons from rapid growth and resource exploitation. Elk County and western Pennsylvania have achieved a measure of success, but they are still grappling with mistakes that may compromise their future.

Sustainable Ecosystem Turned to Wasteland

After the arrival of humans in Pennsylvania some 15,000 years ago, a wave of megafaunal extinction occurred. “Naive” large mammals had no experience with the exotic human migrants. After Pennsylvania’s first inhabitants exhausted the initial bounty, their descendants learned to integrate with local ecosystems. They actively managed the landscape for human sustenance.

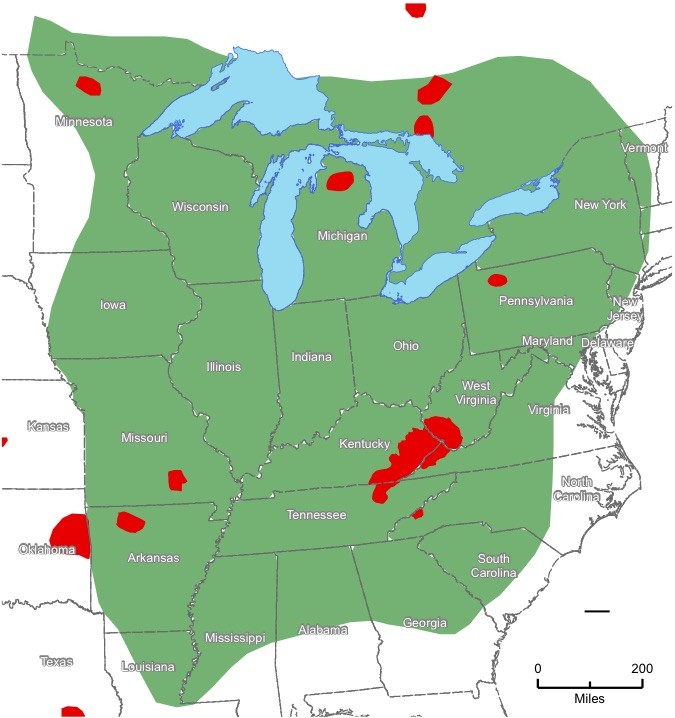

The historic subspecies of eastern elk (green) was extinguished, with successful reintroductions of Rocky Mountain elk (red) in the 20th century. (Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, Public Domain)

Eventually, Lenape and Susquehannock tribes inhabited a region of northwestern Pennsylvania, including Elk County. They used controlled burning to open areas of the forest to agriculture, with gradated tree density that favored certain game, such as deer in intermediate tree cover and elk in the most open areas. The tribes essentially established humans as an apex predator, among others, such as wolves and mountain lions, within a complex ecosystem.

Europeans colonized western Pennsylvania by 1800, driving out most of the native tribespeople who had survived smallpox and other pandemics brought by white settlers. The balance between humans and nature that had persisted for centuries was thus destroyed within a few decades. The Europeans had little appreciation for the complex ecosystem born of the native’s land management, although they did make observational accounts of it.

Efforts to restore the resultant Pennsylvania Desert began in the late 1800s, particularly with the founding of the Pennsylvania Forestry Commission in 1893. The government purchased and replanted land to create a forest reserve system. Wildlife biologists began an effort to reintroduce species such as river otter, peregrine falcon, wild turkey, and white-tailed deer.

Returning a Keystone Species

Elk County is home to a large population of elk. (Brian Czech)

Elk County’s namesake is the North American elk, named wapiti by the Shawnee. Elk are one of the few species of megafauna that survived the Pleistocene epoch, aka “Ice Age.” They played an important role in prehistoric eastern forests, but European settlers rapidly extinguished the eastern subspecies (Cervus elaphus canadensis) through overhunting and habitat destruction. Therefore, the government introduced Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni) in 1913.

Keystone species are vital to the ecological integrity of ecosystems. Elk are considered a keystone species, as they shape their ecosystem’s structure and composition through grazing and seed dispersal, and provide a substantial food source for large predators. Coyotes and black bears still prey on calves and old individuals—mountain lions did in the past—but humans have largely resumed the role of elk’s apex predator in Pennsylvania.

The reintroduction of elk, now numbering over 1,400 individuals roaming the state, is a re-wilding success story. In 2024, ecotourism brought over $3 billion to the Pennsylvania Wilds region, including Elk County. Elk are a significant part of that tourism, with over half a million visitors to the Elk Country Visitor Center in 2019.

Elk County government recognizes this contribution to the local economy in their comprehensive plan (in coordination with neighboring Clearfield County). The plan focuses on developing tourism infrastructure—especially ecotourism centered not only around elk but also highlighting sustainable farming and local food and beverage production.

Yet, under the heading of Economic Vitality and Growth, the plan aims to promote coal and methane extraction. One of the county’s economic development strategies is the Appalachian Regional Clean Hydrogen Hub (ARCH2). This would utilize fracked natural gas—abundant in western Pennsylvania—to create “clean” hydrogen for fuel.

This project is now targeted for elimination by the Trump Administration as part of sweeping cuts to what the director of the Office of Management and Budget called “Green New Scam funding to fuel the Left’s climate agenda.” The federal government has prioritized GDP-growth potential in expanding digital services, data storage, and AI development. However, fracking will no doubt continue—and likely accelerate—with energy demand escalating for powering data centers.

Deep Rooted Danger Beneath the Forest

While Elk County’s ecosystems have recovered from logging over the past century, a legacy of acid pollution continues from the mining of coal, iron, and paint metals. Elk County ranks second among Pennsylvania’s 67 counties for the most miles—1,126—of impaired streams. This is a cautionary tale for further mining endeavors. Some 90 percent of rural Pennsylvanians rely on private wells for their water needs. This population is threatened as groundwater is affected by the surface and subsurface contamination that results from the extraction of coal, metals, oil, and gas.

Like Elk County, seeking short-term revenue, the state government has opted to expand fracking on private and public land. In 2008, then-Governor Ted Rendell opened up state forests for drilling, a decision he later regretted. Now gas well pads dot state and federal forests (including Allegheny National Forest), along with roads and conduits for piping. Expansion of fracking is likely to bring additional groundwater pollution. Forest fragmentation and exotic species introductions are also immediate concerns from the associated roads and conduits.

Elk County is outlined in blue. The top map indicates total wells, with active wells in green, and the bottom map shows fracking wells. (Fractracker Alliance)

What lies in store from the thousands of wells where shale has been hydraulically shattered to liberate methane is not well understood. However, groundwater, streams, and drinking wells have been contaminated with the chemical cocktail that is injected in the fracking process. As described by Katie Jones, the Ohio River Valley Coordinator of the FracTracker Alliance, fracking in areas replete with old abandoned oil wells is risky. In an interview for the Steady State Herald, Jones said, “The risk is that in the process of fracking, the chemicals will find their way into old wells and then make contact with groundwater.”

Jones noted that such an infiltration occurred in New Freeport, Pennsylvania, in Greene County. New Freeport has experienced widespread contamination of home water wells with fracking fluids and methane. Such cases of widespread contamination are known as “frac-outs.” In some cases, the methane levels are high enough to be explosive.

Jones warned that, although Elk County does not yet have the density of fracking that has occurred in the southwest and northeast areas of Pennsylvania, “many of the abandoned wells that were left unplugged are located in the northcentral part of the state—in the Pennsylvania Wilds region. Many of these wells’ whereabouts are unknown, which makes ‘frac-outs’ all the more likely.”

Fleeting Shale Boomtowns

Fracking pads in eastern Elk County are clearly visible in aerial photos. (Google Earth)

The Freeport case is just one of 54 frac-outs that were recorded by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection from 2016-2024. And, as Jones noted, the process of hydrofracturing shale does not just entail a vertical well. “The process involves horizontal drilling for thousands of feet. The fracturing of shale layers occurs over a huge area. We may not know the consequences of this activity for decades to come.”

Short-term gains yielding long-term harm is a familiar story for Pennsylvania counties, such as Elk County. Jones lamented the tragedy of history repeating and described how the current drilling frenzy for natural gas has created temporary “boomtowns.” By current measures, the boom won’t last as long as promised when the fracking began. The U.S. Geological Survey re-evaluated the “Marcellus Shale” formation, which lies below Elk County, and downgraded their estimate of recoverable reserves by 80 percent.

It may well be that the shale boom has reached its peak. Yet, the damage created, like the damage from the logging and mining booms that preceded it, may take many generations to repair.

Captive of Repeated Patterns?

Despite humanity’s remarkable advancements in ecological understanding and knowledge of Earth’s interconnected systems, a pattern of environmental degradation continues. For example, we have clear evidence of the harms of microplastics, persistent organic pollutants, and biodiversity loss. Yet, policymakers continue to prioritize short-term economic growth over long-term planetary and human health.

Elk County and the Pennsylvania Wilds demonstrate that we can collectively repair ecological damage we’ve created via myopic policies. Much of the area’s natural richness and beauty has returned. Nurturing forests, reintroducing elk, and restoring some creeks and rivers has been successful.

But, ignoring lessons about ecological degradation is manifest, too. The rise of data centers powered by a brief surge in natural gas extraction is leaving new scars on recently recovered landscapes.

The rugged, mountainous Pennsylvania Wilds. (Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Public Domain)

This behavioral paradox highlights a significant gap between awareness and action. We understand the need for environmental protection. However, because of ingrained habits, political inertia, and an economy predicated on growth, we repeatedly commit the same environmental mistakes. Keeping our counties great requires healthy dose of insight gleaned from tragic errors.

There is still time to halt the fracking frenzy in Elk County. Doing so will require that government, business, and residents work together to prioritize the elk, the waters, and a local food economy over short-term profits from industries that degrade the county’s natural wealth. Revising the comprehensive plan with indigenous perspectives (ala Bayfield County, Wisconsin), would help safeguard Elk County’s ecological systems. Sustainable (not ever-increasing) ecotourism is part of the solution. Will the people of Elk County heed the lessons of the past and rise to the challenge of creating a steady-state future?

Dave Rollo is a policy specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

Dave Rollo is a policy specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

Your article on mining in Elk County, PA was fascinating and informative. It did spark a memory that goes back to the 1940s when I was growing up in Jackson MS. My Dad was a paint manufacturer and I can remember his frustration occasionally at not being able to receive red lead shipments in a timely fashion. He had a background in chemistry, was well-aware of the potential danger of exposure to red lead and, in a daily effort to protect his growing family from its harm, would shower and change clothes every day after work at the plant. Perhaps these shipments, vital to the making of lead-based paints, came from PA.

Elk County’s area comprises 1.8% of that of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (one fifty-sixth of the total), and it is less than one-sixth the area of Connecticut. Elk County’s population is 0.23% of that of the state, less than 1/400th of the total. Your article is otherwise accurate and thought-provoking, but such egregious errors in description don’t bode well for credibility for many of your readers. Thank you for writing and publishing this. Be careful with your fact-checking.

Roger, thank you for spotting that discrepancy and bringing it to our attention. The second paragraph was intended to refer to the Pennsylvania Wilds, not Elk County. We have revised it thusly and added an editor’s note at the outset. Thanks again!