Game On or Game Over for the Environment?

by Mai Nguyen

In January 2022, Microsoft announced that the company planned to buy the videogame company Activision Blizzard for almost $70 billion, giving it control of franchises like Call of Duty, Candy Crush, and World of Warcraft. This signaled to the world the potential of gaming for the tech industry’s pursuit of speedier growth despite technology being an already high-demand industry.

Microsoft bought Activision Blizzard, usurping many profitable franchises, most notably Call of Duty. (CC BY-SA 3.0, Dinosaur918)

I understand the appeal of video games; I own a couple of consoles, and I keep up with the latest gaming news. While many dismiss them as a waste of time, video games are a medium that enable us to tell incredible stories in a way that movies or books can’t quite replicate. They provide a level of interactivity and customizability that allows the player to immerse themselves in a grand story. I’ve fought to protect my family from Japanese crime society in Yakuza and lived my fantasy life as the homeowner of a castle in The Sims. And just like any other hobby, fans can find communities centered around their favorite games.

But while video games flaunt a unique (and at times addicting) charm, with every growing industry is a dark side of depleting resources.

Growth of the Industry

Video games have come a long way since their simple beginnings, starting with a simple tic-tac-toe game in 1952 before ballooning to a billion-dollar industry. Later, the 70s and 80s brought the release of several milestone game consoles like the Atari 2600 and the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). In 1989, Sega released the Genesis to compete against the NES, triggering the first “console war” and the release of scores of popular games for both consoles.

At the end of 2021, Newzoo reported 2.95 billion gamers worldwide and predicted 3 billion by 2023. The market for video games has only grown in the past few years, thanks partially to the pandemic. As time at home increased, so did new hobbies. From 2019 to 2020, the number of U.S. console gamers increased by 6.3 percent and console sales surged 155 percent worldwide by March 2020.

Nintendo sold more than 14.3 million units of its Nintendo Switch console during the pandemic, likely due to the release of the relaxing life-simulator game Animal Crossing: New Horizons. Similarly, PlayStation experienced an 83 percent boom in game sales in the first quarter of 2020, 74 percent of which were digital downloads.

The Internet has played a large part in video game success, and not just because of online play. The Internet made it possible to play video games as a profession, not just a hobby. YouTube videos, especially “Let’s Play” videos, made it possible for viewers to experience games they were unsure about buying, often with comedic commentary. YouTuber PewDiePie spent 2013 to 2015 as the most subscribed YouTuber thanks to his Let’s Play content and continues today with 111 million subscribers.

Gaming: once merely a hobby, now a global “esport” phenomenon. (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, Maxime FORT)

Twitch also played a significant role in shaping the gaming industry by allowing viewers to interact with their favorite gamers in real time, from voting on how the streamer will play a game to sending direct messages. YouTube, too, has a streaming feature. Polygon reports that YouTube streamers put in 54.9 million hours of content in 2020, versus 55.4 million hours in 2019. Don’t let the slight decline in total content fool you, though. Viewership nearly doubled to 6.19 billion hours in 2020 from 3.15 billion in 2019.

Esports, or competitive video games, is one of the fastest growing industries in the world, with a total audience of 335 million in 2017 rising to 645 million in 2022. The growth of esports and their viewership means more energy and resource consumption required for gaming equipment. Hardware companies encourage customers to invest in the most powerful parts in the market, from processors to entire PCs, a strategy many believe drove the industry to a $1.5 billion value in 2017. And while esports are still a relatively small source of revenue for the gaming industry, BITKRAFT predicts that figure will grow with the introduction of new competitive games.

Today, the gaming industry has at least a $175 billion value (BITKRAFT suspects it’s even bigger), but it could more than double by 2028 as the industry takes advantage of the increasingly widening platform offered by mobile gaming.

A Look inside the Game Case

While the gaming industry has internal issues like the lax attitude towards toxic workplace culture, beefing up the industry spells out something even more ominous for the environment.

Like cell phones, with the hype of each new-generation console, there lies a danger of gamers trashing old consoles for the new model. As of 2022, Nintendo sold 103.5 million Switches. PlayStation sold 116.9 million PS4s, and PS5 consoles braved shortages and hit 17.3 million sales. Of course, these shiny new models come at an ecological cost. To conduct electricity, consoles depend on mined materials including copper, nickel, gold, and zinc. The circuit board and other parts are tucked into a plastic case, which is formed from crude oil and natural gas.

There is more room for customizability with PC gaming. Gamers can buy prebuilt computers with their desired specs, or they can build one themselves. In both cases, however, gamers tend to go for the parts with the most powerful specs. These components require huge amounts of power, with some GPUs using over 300 watts in a ten-minute test run. Such excessive energy consumption is also exacerbated by incredibly tight release dates between new parts. The GPU giant Nvidia consistently releases components collections several times a year.

Nintendo has launched initiatives for recycling hardware and complying with e-waste regulations, but recycling should never be our first resort to solve the waste problem. While e-waste recycling seems like the obvious step to making the industry sustainable, the current state of e-waste recycling has a host of problems. In the formal recycling process, waste is mechanically separated and shredded for further sorting by hand. To avoid the costs of adhering to safety and pollution-control regulations in the USA, companies often export the waste to developing countries for informal recycling. At these workshops, workers recover valuable metals by burning away the plastic devices, leading to hazardous conditions and increased emissions.

Old consoles and PCs get dumped for the newest tech, resulting in considerable e-waste. (CC BY 2.0, Curtis Palmer)

However, nowadays, next-gen gaming is taking on a sleeker look with digital downloads and cloud gaming. But while gaming is moving away from physical game discs, experts say that digital services won’t be the cure-all to gaming-related emissions. Gaming represents 34 terawatt-hours of energy and 24 metric tons of CO2 emissions per year, equivalent to 85 million refrigerators. Cloud-based game subscriptions like Google Stadia or PlayStation Now, which allow players to stream from an online library of games to their device, are highly demanding of servers. These subscription services allow users to stream games from huge data centers, which can cost hundreds of millions of dollars to build, are extremely energy-intensive, and take up almost as much space as ten football fields, all while producing tremendous amounts of heat.

The increased use of centralized technology will pressure game companies to consistently stay up-to-date on the latest equipment, which could contribute even more to the e-waste problem. One study found that cloud-based gaming requires significantly more energy per hour than similarly powerful local gaming equipment.

Video Games for Good

On the bright side, many of the thousands of video games in existence have environmental messages. You can fight as Cloud Strife against the evil Shinra Electric Power Company in Final Fantasy VII, or run renewable energy projects in Sims 4’s Eco Lifestyle pack. You can even explore Central Park through the eyes of a bee and defend your hive from humans in Bee Simulator. Games like these help spread environmental awareness and push the world towards sustainability in a way that no advertisement campaign can; at least, the UN believes so.

Mirai is the protagonist of E-Line Media’s educational underwater diving adventure game Beyond Blue, inspired by the BBC nature docuseries Blue Planet II. The player guides Mirai, leader of a deep-sea research team, as they investigate whales and sea turtles and uncover the secrets of the deep. Alan Gershenfeld, co-founder of E-Line Media, told DW, “The more gamers care about the ocean, the more they want to explore the ocean, avocational or as a career. I believe, that’s the key towards ocean preservation.”

In Eco, players must collaborate to use natural resources to build a civilization and develop the technology to destroy a planet-threatening asteroid. The game gives the players the option to build governments and economies, and each of the players’ decisions has the potential to benefit or harm the environment. Eco is currently still in development and is available for early access, but it already has thousands of positive reviews lauding the game’s teamwork mechanics under its belt.

Knowing minds like this exist in the game industry makes me optimistic, especially considering the growing number of gamers worldwide. And with the industry becoming more mainstream, it’s important that these gamers come to terms with the industry’s flaws and strive to become a force for good.

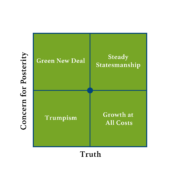

Where Do We Go from Here?

Even if game companies were to wholly commit to environmental protection, the fact remains that gamers never want to buy the least-powerful equipment. These game systems are incredible, and the games look and feel as fun as they do thanks to the massive amounts of resources required to make them. Perpetual growth of any industry can never be sustainable. However, we can also tell that video games aren’t going anywhere anytime soon.

To tackle this issue, we can find gaming’s steady-state potential by focusing on increasing our hardware’s lifespan instead of buying more than we need. While next-gen system release dates largely line up with the end of the predecessor’s lifespan, backwards compatibility between consoles is a rare sight; you can’t play your PS3 games on your new PS4. Providing ways to play older games and extending the life of consoles seem like good first steps.

Digital stores like My Nintendo Store and PlayStation Store offer libraries of classic games, not to mention the new games in development for older consoles. However, whether it’s buying a console or building a PC, it’s tempting to give in to upgrade trends and buy the latest, most powerful innovation in gaming technology. But you don’t necessarily need the very best specs and up-to-date tech to have a quality gaming experience. You’ll survive without a 4K-capable graphics card and butter-smooth frame rates; it’ll be easier on your wallet as well.

But scaling back on new gaming purchases is just one part of the solution. We can also take notes from games like Beyond Blue and Eco by actively using the medium to spread the word about sustainability and steady-state economics. CASSE developed Limits to Growth, a playground game that introduces kids to fairness and sustainability in the context of steady-state economics. To the play the game, players go through rounds within their individual houses, represented by a hula hoop, and one planet represented by a rope. In each round, players have the option to “upgrade” their house by adding another hula hoop. Once the planet is filled up with hula hoops, some students might “die.” This is a fun and easy way to teach children about the foundations of steady-state economics, but developing a limits to growth video game could bring it to the next level.

What if CASSE Joined the Game?

The multiplayer open-world survival genre with sandbox elements is the perfect playground for bringing the message to life. Imagine starting in a virtual world much like our Earth, except it’s completely untouched by human civilization. The virtual Limits to Growth game (perhaps Stable Planet has a catchier ring) begins with choosing the biome—aquatic, grassland, forest, desert, or tundra—where the game will take place. While exploring, players can observe and learn about the biodiversity of their chosen environment. Players may catch lion cubs play-fighting in a savanna, gawk at Galápagos penguins gliding through cool waters, or admire the crystal-blue sky occupied by a V-formation of geese. Players are simply dropped into the colorful, virtual world with nothing but a few basic tools (like a hatchet, bow and arrows, and fishing rod) in their inventories, and they must find food and build shelter to survive.

Mockup game cover for Stable Planet. Do you have what it takes to create a sustainable civilization?

Like in Eco, players live together in a civilization server and make decisions that impact the world around them, from hunting a single deer to clearing out a forest for a village. While collaboration is encouraged, individual players may choose (or not) to build and upgrade their own homes at the expense of natural resources like timber and fisheries. Certain upgrades require more advanced tools, which call for even more raw materials.

Players can eventually vote to build communal structures, such as a power plant for electricity or ports for trade with visiting non-player characters (NPCs) representing different civilizations. Of course, these major upgrades require substantial resources; the gamer sees these resources decline in quantity and quality. Open-world games like Minecraft encourage players to grind away at virtually infinite resources like wood and stone, but Stable Planet would make it clear that resources, including occupiable space, are finite or not quickly renewable.

In the game, with each collective and individual decision, consequences to GDP and the environment follow. The server’s GDP appears as a scoreboard overlaying each player’s screen. The number starts at zero and stays a cool green color until players’ economic activities proliferate. This is a major mechanic in the game, as it may—and eventually should—serve as a driving force for players’ decisions.

One group of players may decide to chase a high GDP and expand production far beyond sustainable, survivable levels. In this case, GDP continuously grows on the scoreboard, with digits increasing on a spinning meter (similar to the CASSE website). If players’ choices lead to furious growth, the scoreboard’s visuals would intensify, the number pulsing red with sparks flying off the board. Some players may interpret this as a good thing. After all, a booming economy is a healthy economy, right?

The state of the environment, however, reflects that high GDP in a different light. To expand iron trading, for example, players may build a huge plant to make mining easier, but a host of environmental consequences ensue; emissions visibly cloud the air and players’ health bars gradually deteriorate, lands lose arability, and wildlife species recede into extinction. While players may simply choose to move their settlement someplace else on the map, the “open” world is not infinite; this process can only be repeated so many times before they run out of space. With nowhere else to go, players die one by one from starvation or illness.

On the other hand, smart players may decide to manage GDP differently. They have the option of building a civilization based on what’s needed to survive. Instead of perpetual building, they can spend more time playing with friends and family, or joining other players in “town hall” meetings. GDP growth will slow, with the scoreboard once again emanating a cool green glow.

One civilization may enjoy an abundance of high-tech toys and a sky-high GDP—with all the problems that come with it—but yours can enjoy the bounty of nature and other pleasures of a good life. Like many open-world games, Stable Planet has no definite end, and instead encourages players to explore different ways to interact with their environment and other players, for better or for worse.

Mai Nguyen is the Spring 2022 editorial intern at CASSE, and a junior at George Washington University.

Mai Nguyen is the Spring 2022 editorial intern at CASSE, and a junior at George Washington University.

"Rappahannock County Courthouse" by taberandrew is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

"Rappahannock County Courthouse" by taberandrew is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

“Gaming represents 34 terawatt-hours of energy and 24 metric-tons of CO2 emissions per year.” Only 24 metric tons????

I should have clarified that figure is within the US; globally, gaming contributes 75 TWh annually. While gaming may make up a relatively small part of global greenhouse emissions at 3.7%, it’s worth noting that the problems with gaming extend to e-waste and overall energy consumption.

Hi

I had contacted Terry Spahr and film producer Paul Goodenough about an idea for a video game. They both liked the concept and I approached a game producing company but we didn’t get anywhere.

If you are interested I’m happy to let you have my “story board” and you can see if it has legs or if you wish to produce it. The game was intended to show the correlation between our numbers and what happens to the biosphere.

Best wishes

EsTerre

Nicely developed article, thanks. I thought to suggest that instead of “basic tools” being those which harm animals (arrows, fishing rod) you might offer the vegan set of hoe and starter seeds. Perhaps have the tools as a choice to compete with each other. I hope your game gets started and thanks again for writing.

Good Article. I think with the release of many eco-friendly games, the youth can be introduced to many forms of protecting our planet