Reduce, Reuse, Rethink: The Problem of Recycling

by Ted Atwood

We’re taught from a young age to “reduce, reuse, recycle.” (WavebreakMediaMicro – stock.adobe.com)

I was born in the year 2000. Thus, for my entire life, human-caused climate change has been an ever-present, intensifying threat. Throughout my early education, I learned that we all just needed to “do our part” to combat climate change. “Do your part” lessons always culminated in the sentiment that you too could save the cute polar bears by following the motto “reduce, reuse, recycle,” and these were words I took to heart.

As an introduction to sustainable practices, this formula isn’t entirely false, but as a greater climate crisis looms on the horizon, we need to rethink our blind faith in this three-step model, particularly recycling. The current practice of recycling (and the industry at large) reflects the flaws of contemporary climate strategy. Assessing the failures of the recycling process can guide us in the direction of a truly sustainable future.

Out of Country, Out of Mind

The first flaw in our recycling model is its reliance on foreign labor and processing. After we toss a bottle into a recycling bin, unless the bottle is pristine and easy to process (increasingly rare with single-stream recycling), it is loaded onto a container ship and sold by the ton to processing facilities on the other side of the world, namely China. With our environmental regulations and high labor costs, it would be literally impossible to handle all the plastic, glass, and paper we produce domestically. Thus, the only profitable alternative is China with its high capacity for materials management, low environmental standards, and cheap labor costs.

China’s ban on plastics forces us to deal with the problem at home. But how are we dealing with it? (CC BY-SA 3.0, Paul Louis)

At its peak, China was the final destination for more than half the world’s recycled waste. This was until 2018, when China developed a new set of import standards, citing environmental concerns—which really meant that even the vast Chinese economy and workforce was inundated with foreign waste. This disruption in the recycling status quo left producers a choice to shut down recycling programs entirely, remove their burden by shipping to even more poorly regulated and dangerous facilities in Malaysia, or incinerate the waste domestically, often dangerously close to already vulnerable communities.

China’s inability to manage the volume of waste reveals the larger issue behind the recycling rhetoric. Rather than address our overwhelming consumption, we resort to pushing the problem abroad. However, the well-intentioned consumer only sees the aesthetically pleasing blue bins, and thinks no further of the plastic’s journey, unknowingly perpetuating the problem. Our collective mental image of recycling as a universal best practice is much easier to maintain when our waste is not only out of sight, but halfway around the world.

Excuses for Growth

Even if our recycling system functioned perfectly, we still wouldn’t be able to call it a panacea or even a significant aid in combating climate change. Why? Because of the linkage between increasing recycling and increasing plastic consumption. Evidently, practicing the “good habit” of recycling justifies our consumption of even more.

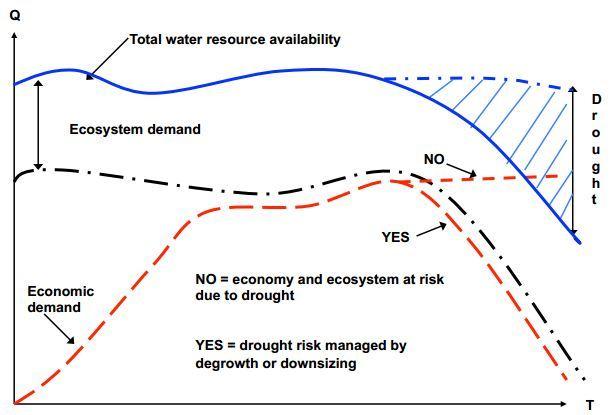

The momentum behind recycling feeds plastics, which of course has a vested interest in promoting consumption. The American Chemistry Council estimates that $186 billion is being invested in 318 new projects to increase plastic production. As we know, the steady state economy is the pinnacle of sustainability, so growth in the plastics and recycling industries is inherently unsustainable. Since the 1990s, the plastics industry has paid for ads that champion recycling as sustainability, driven by the understanding that recycling equals bigger profit. The recycling industry as it exists today, then, effectively becomes a smoke screen allowing for further destructive growth.

Businesses claim they’re “going green” but it’s all for profit. (CC BY 2.0, aboblist.com)

Recycling as an excuse for growth parallels other trends in the “business of sustainability.” While dozens of companies make pledges or initiatives in the name of the environment, these are too often facades or outright lies. After all, what incentive do businesses have to become truly sustainable, when all it takes is a little greenwashing to mislead consumers? Some of the most blatant examples of this include the “clean diesel” propaganda by Volkswagen as an alternative to hybrid or electric vehicles, when in reality software was installed to fool emissions tests, and the cars spewed nitrous oxide up to 40 times the legal limit.

Even beyond cases of clear deception, corporate sustainability goals are really a Band-Aid over a gaping wound. Most companies, like the Shell Oil Company, make non-binding promises to become net zero on carbon in several decades. However, even these programs rely on carbon offsets where companies pay to save forests that would otherwise be logged, and these programs are hard to verify. One program in Indonesia overestimated the effects on deforestation by more than 60 times! In effect, these offsets offer an opportunity to cook the books.

The UN warns that offsets are mere Band-Aids that should be phased out by 2030. Even if offsets delivered what they promised, there is a finite amount of remaining forest to protect, and they do not address the countless other forms of natural capital exploited for economic growth. Just like recycling, neutrality pledges are sustainability smokescreens.

Steady-State Takeaways

The perpetual growth of any industry is inherently opposed to true sustainability and environmental protection. The plastic industry is no exception, even if growth advocates justify their views with the “solution” of recycling. Plastics, made from oil and gas, rely on our petroleum supply and further drilling for production, which we all know causes a slew of environmental consequences. Less intuitively, the same applies for the booming business of recycling, a $53 billion industry expected to grow at more than five percent each year. A growing recycling industry requires more labor (and thus food input), more shipping costs (both domestic and international), and other heavy machinery that necessitates natural capital.

While we should continue celebrating changing habits and moving to a cleaner future, we still need to be wary of complacency and devious marketing ploys. Chartered corporations exist for the sole purpose to make profit, so why should we trust them when they promise they’re committed to sustainability?

Any type of advocacy can feel emotionally exhausting, and the last thing you want to hear is that the few solutions you’ve tried implementing are not what you thought. This article is not a call to burn your recycling bins. The inspiration behind this critique is both the hope and confidence that we can do better at holding ourselves responsible for the failings of our current system.

Salvation will never be as simple as a blue bin next to the trash can, but we’ve known this from the beginning. The task of saving humanity and biodiversity from climate catastrophe will be one of the greatest global challenges ever faced, but real solutions are right under our noses. Remember that mantra, “reduce, reuse, recycle,” we’ve all come to know? Rather than put all our eggs in the recycling basket, let’s not forget the value of the other two components. While the most effective way to eliminate waste is not to consume to begin with, reducing and reusing are the next best methods. By reducing our consumption of plastics and choosing reusable goods, we put another brake on unsustainable growth. That’s what sustainability is really all about.

Ted Atwood is a Summer 2021 intern at CASSE.

Ted Atwood is a Summer 2021 intern at CASSE.

Good to see this article. Good work!

I don’t know when it started but several years ago I learnt that “Refuse” was added to the 3R’s as the first choice. Refuse is the most important one. More recently, many variants have come up with more R’s, especially repurpose, but refuse it clearly the first and most important option.

See this example that shows a funnel model. Recycle is the least desirable and the last option. https://www.roadrunnerwm.com/blog/the-5-rs-of-waste-recycling

Ted–

Thanks for the essay. As you know, some have called recycling the methadone of consumption. As an inveterate recycler, I understand but still act. What about repair as augmented reuse? Many legislatures are considering a right to repair proposal that would make this possible. Check it out!

Tom

Thank you for this article. I live in Ucluelet, British Columbia, one of the most affluent places on earth and we only got curbside recycling a few years ago and still in our curb side recycling glass and crinkly plastic bags like for chips arent allowed so they mostly end up in the garbage. Businesses have to pay for recycling pick up and drop off so many dont participate. So much for recycling being profitable and paying for itself!