Hitting the Pause Button in Colorado Springs

By Dave Rollo

The Front Range, where the Great Plains meet the Rockies (Salim Virji, Flickr).

El Paso County is in the eastern foothills of the Rocky Mountains in a region known as the “Front Range,” the mountains first encountered by settlers traveling westward from the Great Plains. The Front Range includes such wonders as Mount Blue Sky and Pikes Peak. But it also refers to a chain of cities and the urban spatial expansion between them that has propagated within and along the foothills. This Front Range Urban Corridor runs in a longitudinal band through the middle of the state of Colorado from Cheyenne in the north to Pueblo in the south. In total, it forms about 200 miles of built environment.

The corridor extends through eleven Colorado counties and is home to approximately 85 percent of the state’s 5.8 million population. This urban band has experienced some of the fastest population growth in the country, with metropolitan areas such as Denver expanding to merge with nearby Boulder and Aurora. Continued unrestrained growth could make the Front Range into a megacity in the coming decades.

The Land Politics of Colorado Springs

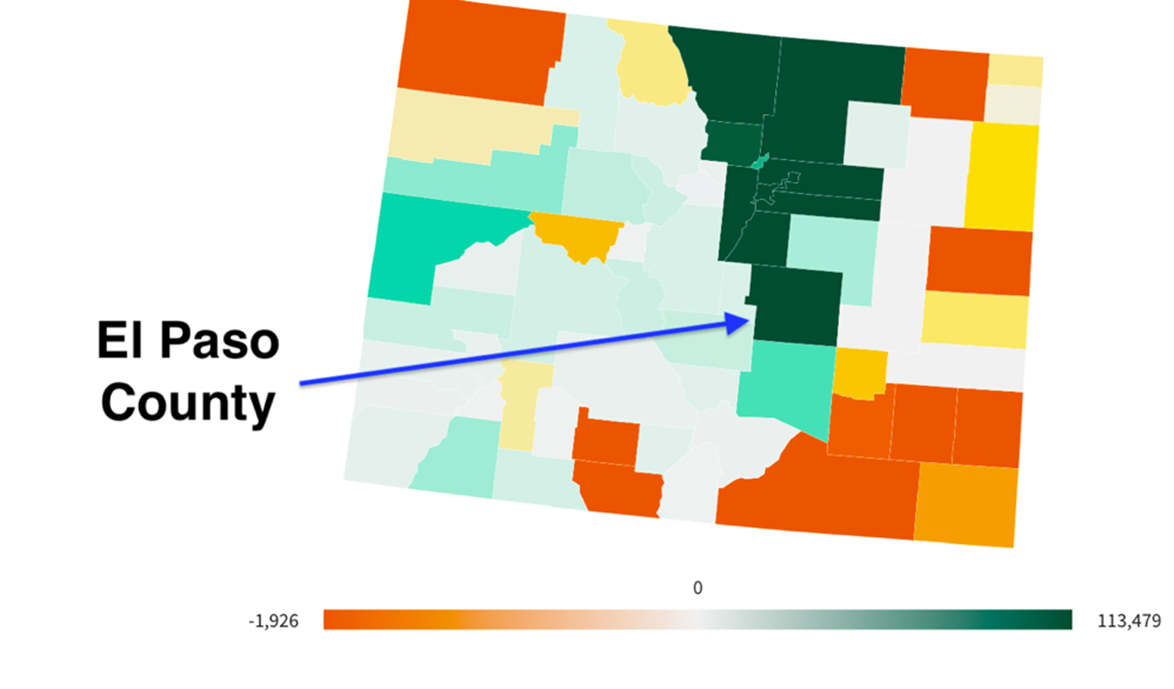

El Paso County, located within the Front Range Urban Corridor, is the fasted growing of Colorado Counties. It added 113,479 residents between 2010 and 2022 (USAFacts, Our Changing Population: Colorado).

El Paso County has been on a near constant population growth trajectory of 17 percent per decade. At this rate, the county’s current population of 740,000 will exceed over a million residents by the late 2040’s. Most of that growth is expected to take place in Colorado Springs.

Colorado Springs is the second most populated city in Colorado, and the most extensive in area. It ranks among the top cities for sprawl. With 25 percent greater area than nearby Denver, it only has 65 percent of its population. Yet, far from taking measures to control the sprawl, El Paso County has designated 192 square miles of county land outside the municipal boundary as suitable for new development. This would nearly double the current municipal area of 202 square miles.

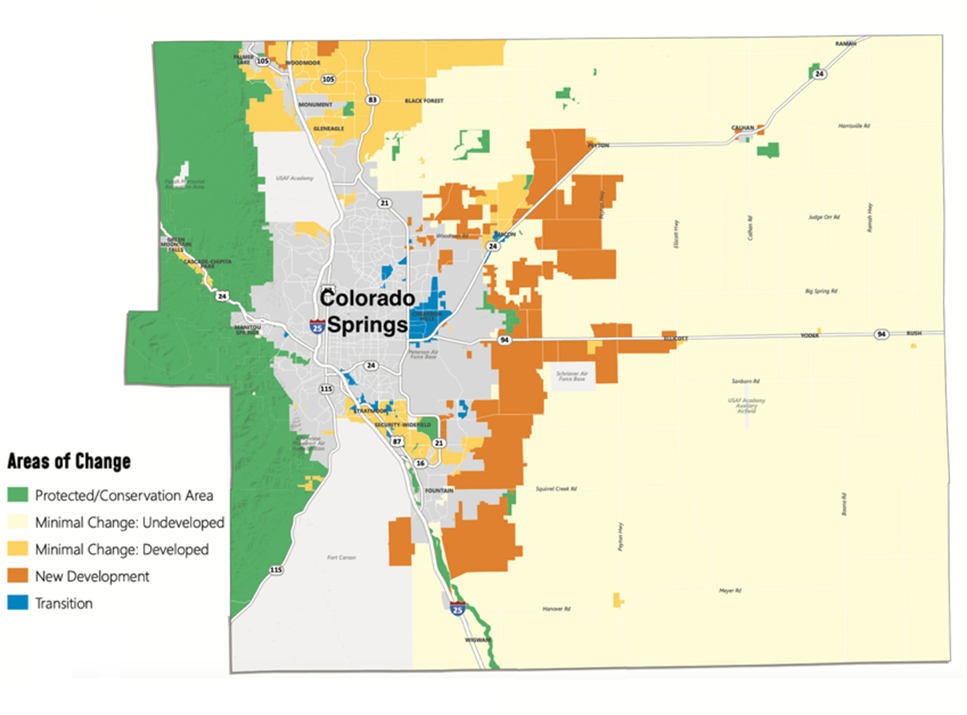

Recent analyses predict Colorado Springs may approach one million residents by mid-century, surpassing Denver as Colorado’s most populous city. Seemingly conceding to this “inevitability,” the El Paso County Comprehensive Plan has designated a swath of land on the eastern periphery of Colorado Springs as an “Area of Change” deemed suitable for new development. But is it really as suitable as the planners say?

The El Paso County Comprehensive Plan invites growth (dark orange) up to 15 miles from the current municipal boundary of Colorado Springs. Green indicates mountainous terrain prone to fire (El Paso County Planning).

The evidence indicates that growth is now encountering definite regional limits. These limits include physical constraints such as mountains, recurrent wildfires, and water scarcity typical of the state’s arid east. This scarcity will likely increase in the coming decades, as global heating causes more frequent droughts and higher temperatures. Furthermore, lower snowpack is projected to reduce the flow of mountain streams by up to 30 percent, further taxing a vital resource.

An increasing number of El Paso residents feel that the current pace of development threatens their quality of life. Meanwhile, local land politics have been largely in lockstep with developers’ interests. The latest municipal election in 2023 saw substantial sums of campaign contributions to mayoral candidates with growth-aligned interests. Developers, realtors, banks and construction companies have poured large sums of money into mayoral campaigns.

But there are also some steady-state rumblings. In recent land-zoning decisions, local elected leaders have actually stepped up to their constituents’ concerns.

When Urban Growth Meets Ecological Limits

Ecological constraints are already imposing harsh limits on growth. The western fourteen percent of El Paso County is bounded by mountainous terrain. The County’s Comprehensive Plan describes the area as mostly protected/conservation state and federal land. The forests are highly susceptible to fire; development is perilous. Over twenty wildfires occurred in this area in less than ten years (2011-2018). The two largest, the Waldo Canyon and the Black Forest fires, incinerated 138,000 acres and destroyed over 800 homes, cost 4 lives, and required thousands to flee. Waldo Canyon property losses alone totaled nearly half a billion dollars.

Colorado Springs wildfires, 2012. (Wikimedia)

While fire is a natural feature of this ecosystem, a century of fire suppression policies and an increasingly hot and dry climate have exacerbated the problem. Human habitation of the forestlands has also increased the risk that wildfire poses to people and property. In response, planners have designated these areas a “Wildland Urban Interface” unsuitable for further urban development.

However, while the western portion of the county may now be protected from growth, the eastern 70 percent consists mostly of undeveloped plains. This region provides crucial ecosystem services for farms, ranches, and wildlife. These considerations are at best a footnote for developers, who have slated the area as ideal for urban development.

Limited water resources have done little to compel more prudent planning, either. Rather, water shortages have stoked competition, leading to struggles among land interest groups.

Leapfrogging and Flagpoles

Regular Coloradans, however, feel differently about the planned urban development. A 2022 poll indicated that nine out of ten Coloradan voters feel that Colorado has developed too much or as much as it should. Only eight percent of those polled believe that more growth is needed. Furthermore, for 62 percent of voters, the county’s urban development “has made the state a worse place to live.” In the 2024 defeat of Amara, the county’s largest development proposal in decades, we finally have tangible evidence that Coloradans’ concerns about growth are being heard.

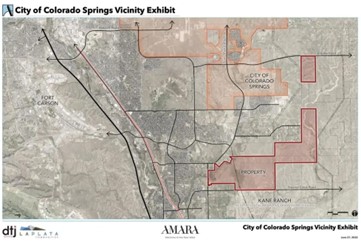

Amara is a proposed 3,200-acre addition to Colorado Springs involving two parcels. One is a contiguous area of over 2,800 acres. The other is a smaller area of 329 acres connected to the city boundary by a narrow stretch of land known as a “flagpole”. This mammoth development would initially consist of some 9,500 residences. This would include single and multifamily apartments, plus schools, a fire station, and commercial/retail uses. To provide sufficient services, the Colorado Springs Utility (CSU) would have to extend sanitary sewer, water, natural gas and electricity to the parcels. By some estimates, the population of the annexed area could be 100,000.

Amara property annexation proposal. Submitted for public record to the City of Colorado Springs.

AnnexCos, the annexation plan for the city, did not anticipate annexing this area as it leapfrogs planned service boundaries. But despite this, the city administration proceeded with vetting the proposal submitted by the developers to the planning commission, the utilities board, and other city agencies. Having passed through these reviews, the final step of approval was a vote before the Colorado Springs City Council. The council held two votes, one at a preliminary hearing on July 23, 2024, and a final decision three weeks later on August 13th.

Citizens Push Back

Many residents of the county and Colorado Springs sounded the alarm about Amara during the council’s summer meetings. Maggie Hannah, a 4th generation rancher, gave impassioned testimony in opposition to the annexation at the July 23rd meeting. Maggie reminded the council that the farmers and ranchers are those “who provide the food, fiber and ecosystem services to the people of the Pike’s Peak region.” She pleaded with the council to consider “that the decisions you make today are what will force us out of ranching… The wheels of growth have ground many of us into the ground.”

Other residents expressed concern that the development costs would be passed on to them through tax and rate increases. Councilmember Nancy Henjum warned that the costs would appear as higher rates for residential utilities and as higher costs for products and services from local businesses.

Corroborating these concerns about costs, Colorado Springs Utilities (CSU) officer Lisa Barbato detailed the massive expenses that have already accrued. At the July 23rd preliminary council meeting, she revealed the city’s plan for “very aggressive” spending, including an additional $3 billion in outlays. This would constitute an enormous expenditure when one considers that the total utilities assets equal $4 billion. Much of her focus was on city and regional water availability. Barbato explained that the city’s water supply shortfall is already 26 percent. The development of Amara would make this shortfall rise to 53 percent.

The last local citizen to speak at the first council meeting was Margaret Radford, former Colorado Springs Councilor, former construction facilitator for CSU, and utilities consultant.

Radford spearheaded the Southern Delivery System, which began operating in 2016 and is the largest water delivery system in the state. The project brings nearly 100 million gallons per day from the Arkansas River Pueblo Reservoir to Colorado Springs and other regional communities. Radford reminded the City Council that it had a “regional responsibility” when it comes to development and water. Referring to Lisa Barbato’s presentation, she sounded the alarm: “City staff are not allowed to tell you ‘no’–have you noticed?” It seems that the shrouding of the “800-Pound Gorilla” of economic growth occurs at local as well as federal levels of government.

Radford wasn’t the only former elected official to oppose Amara. In an opinion piece in the Colorado Springs Gazette, two former mayors of Colorado Springs warned of the massive costs of services and infrastructure that would come with the project. Apparently, it is much easier for officials who have left office to speak out, than those who currently occupy office.

But, despite the compelling testimony from ranchers, farmers, a spectrum of citizens skeptical of city growth, and experts such as Margaret Radford who effectively stated that city staff were “gagged” from providing a negative recommendation, the council voted to affirm Amara in a 5-4 decision.

An Anti-Growth Advocate?

One of the five councilors who supported the preliminary vote for annexation of Amara was Dave Donnelson. Donnelson has a record of challenging developer proposals and influence. In May 2024, for example, Donnelson attempted to have a measure placed on the ballot to prevent the construction of buildings taller than 250 feet where they could obscure views of the mountains. This measure was defeated by his council colleagues.

In June 2024, he butted heads with his colleagues again during a debate on another controversial project, the Arrowest Apartment Complex. Many hundreds of letters, 95 percent in opposition, poured in. Some expressed concern the project would threaten the Garden of the Gods, a spectacular park nearby. Others were more concerned about adequate roadway capacity in case of fire.

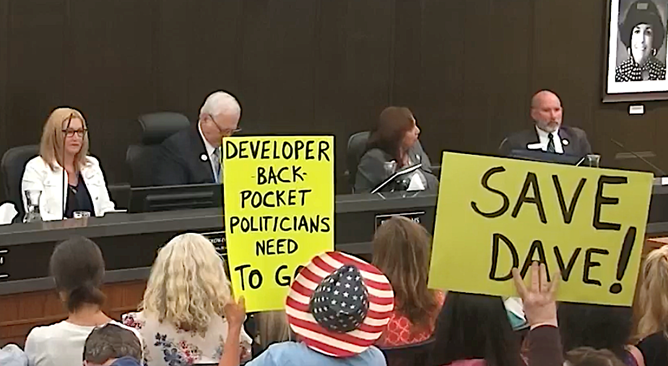

Councilor Dave Donnelson (far right) speaking in his defense during the Colorado Springs City Council meeting held for his censure (City of Colorado Springs).

In response to popular concerns that four councilmembers were influenced by campaign donations from the developer, Donnelson asked his colleagues to consider recusing themselves. In response, the council censured Donnelson, despite vociferous support from his constituents. The complex passed in a 6-2 vote.

Councilor Donnelson said his constituents motivated him to question developer influence. He mentioned in a press conference that he had received hundreds if not thousands of emails of support. Clearly, he was tapping into a growing popular sentiment. Yet, despite Donnelson’s strong anti-development record, he was one of the 5 yay votes in the preliminary approval of the Amara project on July 23rd.

A Turning Point for Colorado Springs?

Still, after his preliminary vote on the Amara project, Donnelson continued listening to the concerns of farmers and ranchers. At the final meeting on the annexation of Amara, he astonished many in attendance by reversing his preliminary ‘yay’ to a ‘nay.’ “It is wrong to let our city become something that the majority of our citizen’s dislike: too big, too crowded, too dense, too tall and too noisy.” Donnelson concluded by adding that “Citizens are beginning to doubt that we, the city council, represent them!”

After this stunning reversal, Donnelson’s council colleague Nancy Henjum, who voted with the majority in the 4-5 defeat of the annexation, pointed to the constraints encountered by city growth. She acknowledged an “insatiable, unquenchable thirst for water that’s harming a greater system.” Testimony by the public clearly swayed Donnelson’s shift from a “yes” to “no.” Donnelson remarked that “Our citizens want a slower rate of growth for our city, and that doesn’t only mean annexations. It also means a slower rate of growth within our city’s boundaries. I will work to provide that option. Our citizens cannot lose faith that we truly represent them.” After the defeat, the developers of Amara indicated that they would not attempt to bring the project back. The Council vote effectively killed it.

Colorado Springs faces an uncertain future of whether to continue its unsustainable and costly expansion. But it is apparent that citizens skeptical of growth are starting to finding representation despite the influence and political power of the urban growth contingent. The denial of the proposed Amara development is a hopeful and major step for Colorado Springs in recognizing local limits.

Dave Rollo is a policy specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

Providence RI is workig on its every 10 years comprehensive plan. Wer are also facing an administration hell bent on growth whereas the community wants clearner air and less asthma. I regularly point out gettinng right on cliamte and on equality is the only way to prosperity. Each year a few more pay attention.

The little borough of Swarthmore, PA is facing its new comprehensive plan process. I would like to limit or stop growth, or even reverse it if there were a way, but I also recognize that the population of the US keeps growing, and there is a huge housing shortage, resulting in overburdening people with housing cost and a huge working homeless population. Dave, I haven’t seen a reply to previous comments I’ve made in the Keep Counties Great vein. How do you recommend squaring these competing concerns? And how do you post a giant Keep Out sign on one’s municipality or county? How do you show kindness and hospitality to the stranger but also get them to go away?

Wonderful to read this article. People are opening their eyes to the devastation we are causing to Earth and our very existence!

Here in the Willamette Valley Oregon region we are facing similar growth pressures. Same for Central Oregon where Bend, OR is the poster child for development and growth gone crazy and very expensive. Those who were raised in Bend can no longer afford to live there. While we are talking about constant land development we also need to talk about population growth, as it has certainly played into this. We need to support zero population growth and fee birth control for all. As we have seen the costs of housing go up, we also need to appreciate all the reasons for that, including real estate investors buying up good housing only to place it in the short term rental market for vacationers business model. This has happened here on the coast and in places like Bend. Places where people want to go, and these places are marketed like crazy, creating more demand for long and short term accommodations. As the population grows, this has the effect of creating a large swath of those who have enough money to afford the current economic conditions, so sellers of anything don’t have an incentive to go low on pricing. This then leaves those at the bottom of the economic ladder in bad shape, as they have fewer options for lower priced goods.

Unfortunate that this article comes off as NIMBYism, providing no solutions (such as allowing more dense land use, taxing land values) and lionizes pure nonsense land uses (ranchers/farmers do not provide “ecosystem services” and their land uses in a desert are to use water far in excess of residential populations).

Agriculture is the largest water user in Colorado, accounting for about 90% of the state’s water use.

Your insane ignorance is showing, as well as your hatred of agriculture and small town life. Why are you on a website for steady state economics with such astounding bigotry towards the very people who would benefit from steady state economics?

And so what if agriculture uses a lot of water? It uses it productively, growing every essential thing that we need that doesn’t come from mining. I live near Colorado Springs and work in water rights engineering with both the cities and farmers. People here themselves don’t want endless growth and there is a wide opening for policy makers to propose alternative economic models not based on endless sprawl.

Agriculture in SE Colorado can become more efficient, but there are trade offs, such as increasing salinity when you switch from flood irrigation to sprinkler or drip irrigation. Crops then become salt limited, rendering them unable to uptake water from the soil.

You really need to wise up and learn some things. These are very tricky, complicated problems we’ve created in the American West, and foolish reactionaries like you only make the work harder.