In the Poconos, They’re Keeping Carbon County Great

By Dave Rollo

Tank Hollow Overlook, amidst the ridges and valleys of Carbon County. (Wikimedia Commons)

In Carbon County, Pennsylvania, the conservation ethic runs deep. It manifests in the county’s comprehensive plan, its “return on environment” analysis, and most recently, a fund to preserve open space, which voters overwhelmingly supported.

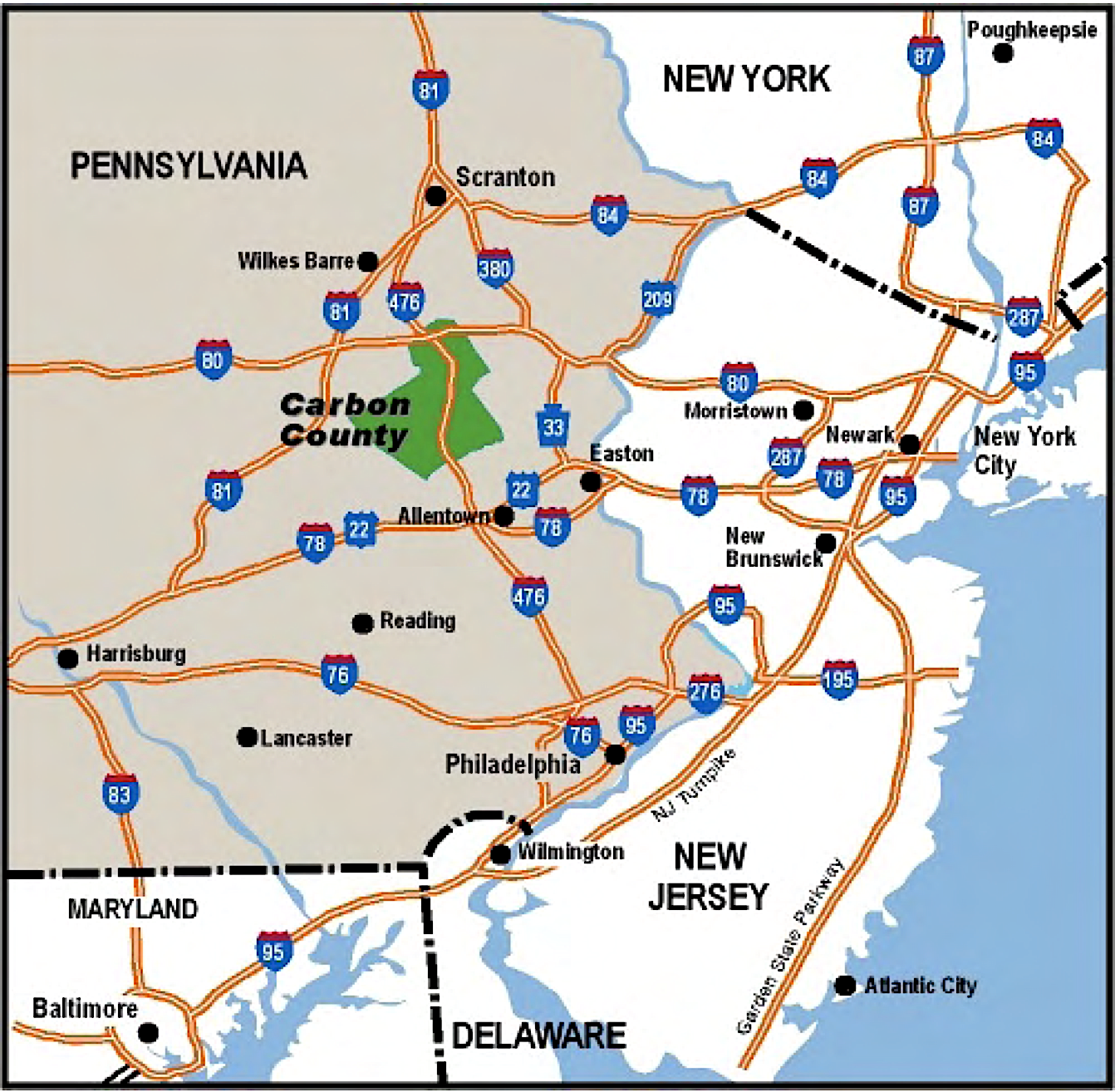

Carbon County derives its name from the abundant deposits of anthracite—the highest quality coal—that were once mined there. The county is located in the southern Pocono Mountains, in eastern Pennsylvania. It is part of the ridge-and-valley system of alternating mountains and river valleys that run along the nearly 1,200 miles of the Appalachian range.

The Poconos are some of the ecologically richest mountain ranges in North America. A natural heritage inventory for Carbon County, conducted by the Nature Conservancy, lists dozens of areas of “highest quality.” The county features wetlands, woods, barrens, and rare ridgetop dwarf forest communities.

Carbon County has had a population of no more than 65,000 residents for over a century. Its GDP has fluctuated at roughly $2.5 billion for the past decade. Its dominant economic sectors consist of information technology, health care, manufacturing, and outdoor recreation and tourism. Carbon County’s population stability and lack of sprawl are notable considering its proximity to large population centers such as Philadelphia (80 miles) and New York (120 miles).

Mounting Development Pressures

Historically, the ridge-and-valley topography acted as a barrier to westward migration. Steep slopes and the wetlands and swamps that occupy the lowlands present natural limits to development. They limited settlement along the Lehigh River, which runs through Carbon County.

Carbon County’s proximity to large metropolitan areas makes it vulnerable to development pressures. (Carbon County Comprehensive and Greenway Plan)

While natural barriers remain, the prospect of development and sprawl is ever present. The Allentown-Bethlehem-Easton metro area lies just 15 miles to the south. Interstate 476—the Pennsylvania Turnpike—bisects Carbon County on its way from Scranton to Philadelphia. The turnpike facilitates data centers and shipping warehouses, so-called “inland ports” that serve retailer platforms such as Amazon.

These facilities require enormous amounts of physical infrastructure, sprawling to expand e-commerce. Furthermore, a shift to telework during the COVID pandemic enabled migration of urban dwellers to rural counties. This has contributed to rural development pressures evident in neighboring counties, including Monroe County to the east.

But Carbon County remains decidedly conservation-minded. County lawmakers, planning officials, and citizens work together to stave off development pressures in their rural sanctuary. Their dedication to preserving their landscape is evident in the county’s land-use planning and return on environment analyses. And recently, grassroots commitment to funding open-space preservation has established Carbon County as a champion of conservation.

Commitment to Land Preservation through Land-Use Planning

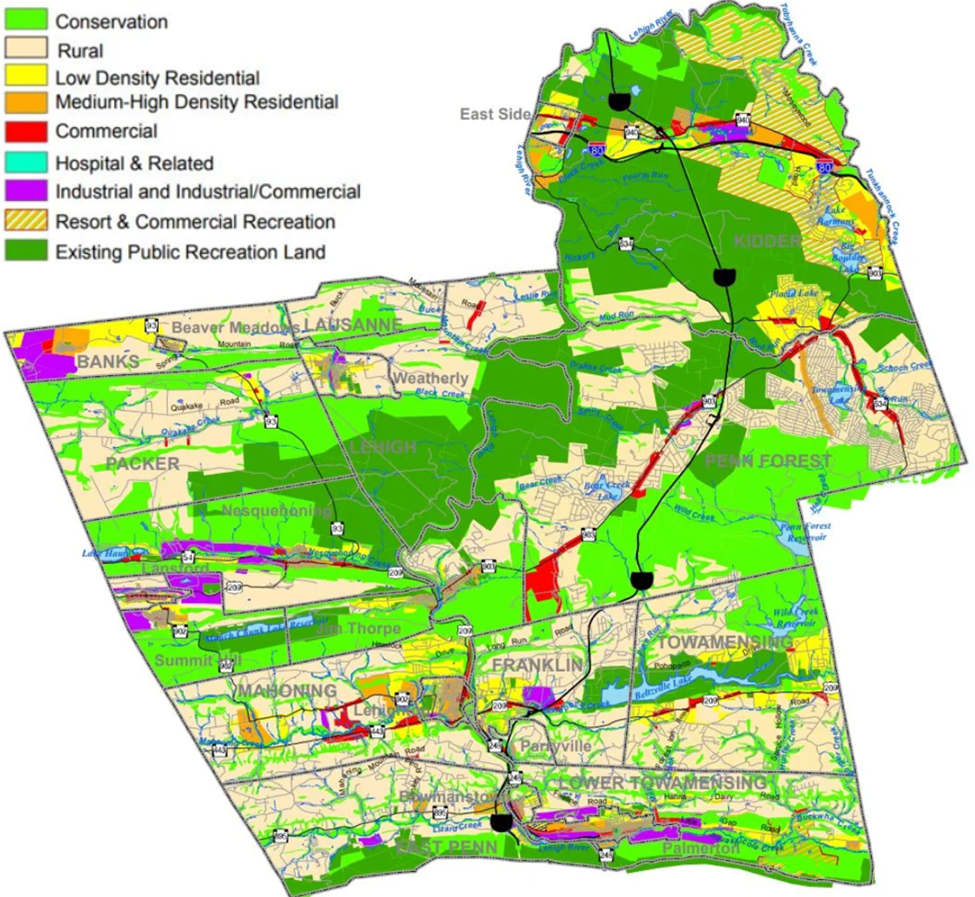

Large tracts of land in Carbon County are dedicated to agriculture, conservation, and public recreation. (Pennsylvania State Game Land)

The primary guiding document for planning in cities and counties is the comprehensive plan. The comprehensive plan differs from the zoning code—the local laws that apply to developing property. Comprehensive plans incorporate cultural and natural identity and present an integrated vision of how a county will develop. Zoning codes provide specific regulations for land development designed to ensure implementation of the comprehensive plan.

From a steady-state perspective, limitations on human development and preservation of land for food production and ecosystem services should be paramount in comprehensive planning. The extent to which growth and structural development compromise a county’s biocapacity can be quantified with ecological footprint analysis. Comprehensive plans complement such analyses by expounding on the means to mitigate development and protect biocapacity.

For Carbon County, the 2013 Comprehensive and Greenways Plan placed high value on preservation of natural areas. It is under revision as the Carbon County Implementable Comprehensive Plan. The April 2025 draft leads with the following vision:

Carbon County envisions a future where sustainable development harmonizes urban vitality with natural preservation. Our community will strategically concentrate growth primarily within existing urban centers, creating vibrant, interconnected neighborhoods that are thoughtfully linked through a comprehensive network of greenways and open spaces. These green corridors will not only preserve our natural landscapes but also provide recreational opportunities, enhance environmental quality, and maintain the unique character that makes Carbon County a desirable place to live, work, and explore.

Evaluating ROE: Return On Environment

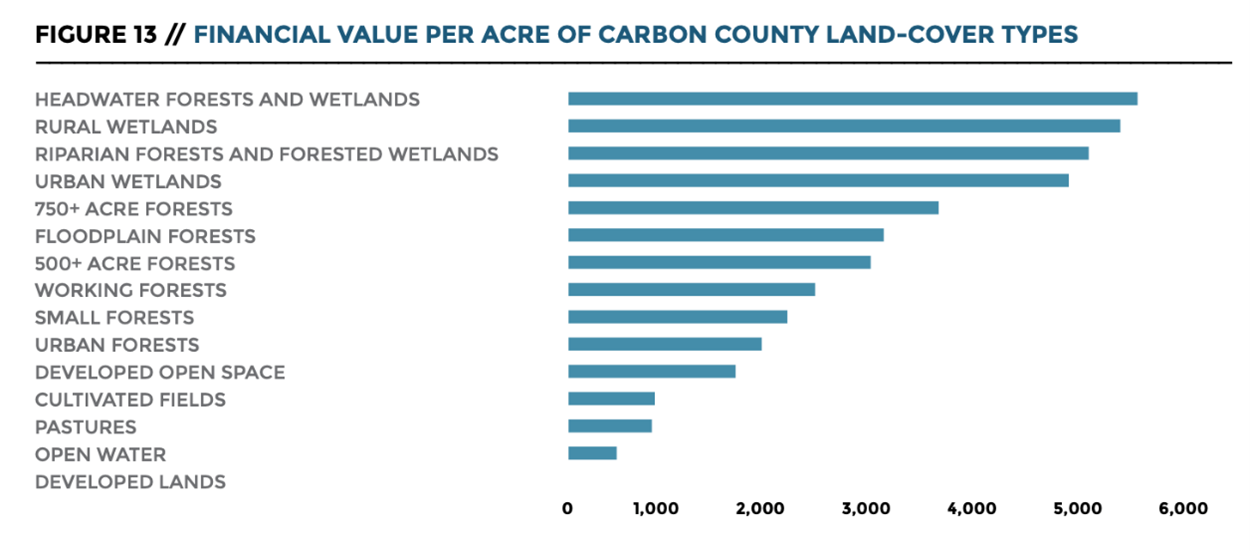

In the same vein as an ecological footprint analysis, Carbon County’s 2018 Return on Environment Report is an important complement to the comprehensive plan. Audubon Pennsylvania and a consortium of conservation groups produced the report. It is one of several reports covering counties in the Kittatinny Ridge region. Researchers evaluated the economic “return on environment” of different land types within the county, incorporating multiple variables into their analysis.

Return-on-environment map of Carbon County with colors representing land values per acre. (Kittatinny Ridge, Return on Environment: Carbon County, 2018)

They estimated costs of “bads” associated with development, such as air pollution, that the county avoids thanks to natural system services. The return-on-environment report also estimates the value of open space in terms of goods and services related to outdoor recreation. Additionally, it incorporates the effects of open space and water on property values. The resulting land values are plotted on a map that aids planners and policy makers in evaluating land uses and prioritizing conservation.

Conservation advocates and county commissioners have used the return-on-environment report in making the case for preserving farms, forests, and wetlands. The report was also a potent tool in promoting a local tax that complements land-use restrictions in the county. The tax is used to fund open-space preservation. Funding goes toward compensation of landowners for keeping farmland in use and toward watershed and wildlife habitat protection. The tax was instituted after a ballot referendum, which allowed residents to weigh in on land preservation.

A Campaign to Fund Open Space

Dennis Demara was formerly the Parks Director for Carbon County and is now Outreach Director for the multicounty Wildlands Conservancy. He and Dan Kunkle, the Director of the Lehigh Gap Nature Center, were principal advocates and organizers for a nine-month campaign to generate support for the preservation-tax referendum. The issue of open-space funding caught Demara’s attention when a member of the local Agricultural Land Preservation Board approached him about protecting family farms. The board wanted to protect over 900 acres of family farms in perpetuity, but lacked the matching funds necessary for state support.

The campaign for the ballot referendum on a land-preservation tax was a grassroots effort. Advocates started from square one, with next to no cash. Their task was to convince a solidly conservative electorate (traditionally, the county votes Republican 2:1) to increase their annual property taxes by $10-$21 per household. The campaign had a clear and compelling message: Implement a tax to finance a $10-million bond for the preservation of watersheds, farms, and undeveloped land.

County bonds are a common approach to raising money quickly from investors. They are similar to loans, but instead of coming from a single lender, bonds are sold in the market by institutions such as brokerages, banks, and bond dealers. At the local level, bonds typically fund specific public projects. In county conservation scenarios, capital raised from the issuance of bonds can supply the matching funds needed for state watershed and land preservation programs. Then, a tax can be implemented to pay the bond debt and interest. While this may seem like a roundabout way to finance conservation, it enables counties to make large, upfront investments to protect rapidly disappearing open spaces.

In the case of Carbon County, conservation bond proceeds would be under local control. A citizen board would determine allocations, and county commissioners would make final decisions. Organizers designed messaging to correspond to the results of a public poll conducted before the ballot referendum was crafted.

In an interview with the Steady State Herald, Demara shared that the poll indicated residents appreciate the value of recreational tourism and enjoy fishing, hunting, and hiking themselves. It also showed that residents support expenditures of up to $10 million for their three top priorities: water quality, working farms, and wildlife habitats.

During a January 2022 county commissioners meeting, Demara made the case to put the tax on the ballot for the general election in November of the same year. Demara testified that:

“The county’s economy is based largely on our natural resources—the Lehigh River, our streams, our parks, our forests, the Christmas tree production…and the family working farms. We know there’s growth pressure. We need to protect our water, our forests and our amazing scenic and rural character.”

The relative land values detailed in the Return on Environment Report for Carbon County make a strong case for preservation. (Kittatinny Ridge, Return on Environment: Carbon County, 2018)

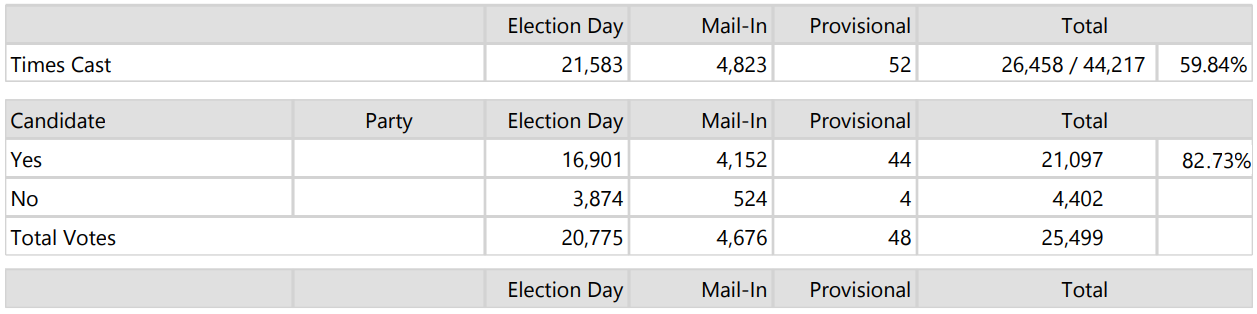

During the January meeting, Commissioner Wayne Nothstein declared support of the ballot measure. He saw it as essential for “maintaining the quality of life, not only for ourselves, but for our visitors.” Yet he cautioned that, since the burden would be placed on property owners, “it is definitely necessary to put it out to the voters and let them make the determination if we should move forward and actually make the obligation of the bond.” Referring to his colleague Commissioner Ahner, Nothstein went on to say, “Rocky hit it spot on…if (the vote) is just 50 plus one—that’s a different decision versus if it’s 75 percent that decides in an overwhelming majority.”

Commissioner Nothstein, referring to the Carbon County Return on Environment Report, affirmed that the tax was in the economic interest of county government and residents alike. At the time of analysis, undeveloped land provided offsets of some $800 million in costs. (For example, undeveloped land helps reduce the need for water purification and treatment utilities.) Commissioners Nothstein and Ahner voted in support of the referendum.

A Strong Community Response

Once the county commission approved the referendum, the onus was on local campaigners to generate a strong majority in support of the ballot measure. The clock was ticking, with less than a year until the general election. The campaign spun into full gear, with the creation of a logo featuring a “Water, Farms, and Land” preservation theme. Demara described the effort as “direct interaction” with over 80 community groups. Conservation organizations such as the Trust for Public Land and The Nature Conservancy were critical in laying the groundwork for the referendum.

Election results from the Carbon County Water Quality, Working Farms, and Wildlife Habitat Protection referendum. (Carbon County Government)

Committed to political neutrality, the campaign focused on themes that emerged from the results of the public poll. They raised over $50,000 in donations for commercials on local television, ads in newspapers, and social media content. Activists distributed yard signs, and events featured a stuffed animal, dubbed “Ricky the Referendum Raccoon,” that traveled the county.

Demara said he couldn’t believe the election-night results. The referendum to support county-wide watersheds, wildlife habitats, and family farms was supported by a whopping 82.7 percent of voters. The campaign had succeeded beyond the organizers’ most optimistic expectations. The tax was implemented, the bond went to issuance, and an Open Space Advisory Board has already begun preservation efforts, advised by regional organizations, such as Wildlands Conservancy, Natural Lands, and Audubon Mid-Atlantic. Carbon County is using proceeds from the bond to compensate landowners for preserving land and to purchase land outright for preservation.

Wide-Ranging Implications

County collaboration could preserve much of Pennsylvania’s remaining open space. (Jakec, Wikimedia Commons)

Out of the 67 counties in Pennsylvania, 34 have populations of less than 90,000. These sparsely populated counties account for over half of the state’s land area and have considerable open-space preservation potential. The few that have adopted funds for land protection—like Carbon County—serve as inspirational examples for preserving biocapacity and ecological integrity. Indeed, successes in other counties helped motivate the Carbon County referendum campaign. State government more than matched neighboring Monroe County’s open space fund, providing three times what the county was able to raise.

Counties can cooperate and help each other in the process of preservation. In May 2024, Carbon County and next-door Northampton County signed a memorandum of understanding to collaborate on Carbon County’s open-space program. Such collaboration can help protect natural features such as the Lehigh River, an impaired waterway that runs through Monroe, Carbon, and Northampton Counties.

Return-on-environment studies can foster understanding that there are economic costs to development. Such understanding incentivizes preservation policies and even conservation taxation. From a steady-state perspective, return-on-environment studies are incomplete. However, they are precursors to ecological-footprint and cost-of-growth analyses that would truly bring local government into the realm of steady-state policies to Keep Our Counties Great.

Dave Rollo is a policy specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

Dave Rollo is a policy specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

Wow! The situation in Carbon County parallels what I see in my nook of the California Sierras (Tuolumne County).

I’m extremely intrigued by the story that a traditionally conservative electorate (check) was able to perceive that natural beauty was key to the regional economy (check) and was able to connect the dots and vote accordingly. I will try to study this story more, time permitting.

Hi Cole, You can check out the ROE studies we have funded throughout the Kittatinny Ridge Conservation Landscape here (https://kittatinnyridge.org/explore/roe/roe-studies/). We find that being able to put a dollar amount to ecosystem services is helpful when discussing the benefits of land conservation. Best of luck on the west coast!