Okeechobee County: Kept Great with Conservation

by Dave Rollo

The Everglades: a county, state, and national treasure (Everglades Aningha Trail Pond, Wikimedia Commons).

Okeechobee County is located in Florida’s Heartland Region, within the 3000-square mile Kissimmee River Basin. The Heartland stretches from Orlando in the north to the intertidal coast of mangrove forests to the south, forming an area commonly referred to as the “River of Grass.” Water flowed hundreds of miles through this enormous network of marshlands, helping to shape an ecosystem of unrivalled subtropical biodiversity.

Today, the Okeechobee wetland system has shrunk to half its former glory. Agricultural, residential, and commercial development has brought red tides, poisonous algal blooms, fish die-offs and the attendant costs in health and quality of life. Red tides have become so severe that they present a breathing hazard. And the environmental impact to this ecosystem is not limited to people living close to the wetlands. One-third of Floridians rely on the Everglades for clean water, so for-profit development of the Okeechobee system entails profound downstream repercussions.

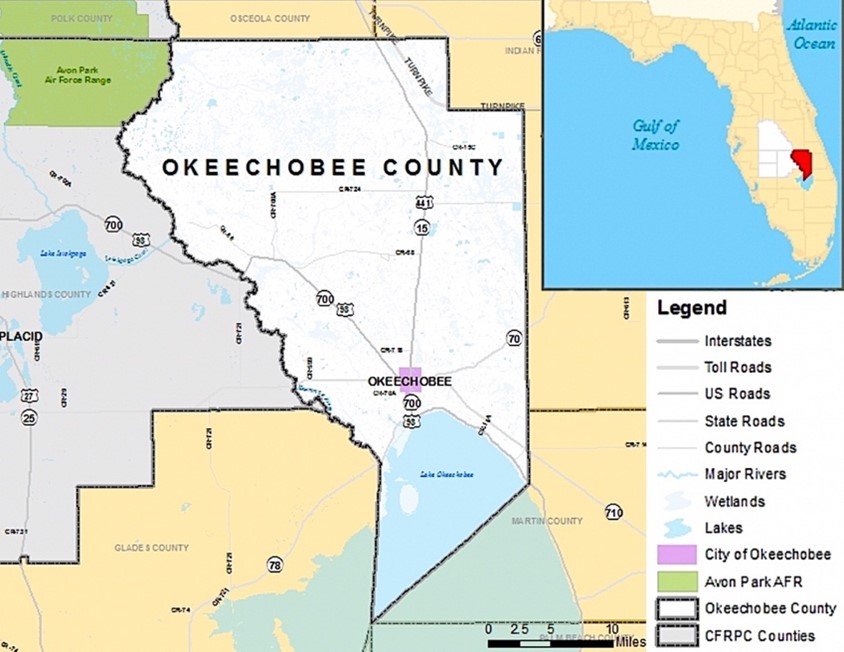

Okeechobee County, in the Heartland Region of Florida (Okeechobee County Location Map, Central Florida Regional Planning Council).

Thankfully, we may be regaining an appreciation for a region once thought of as unproductive “swampland.” In recent years, the state has sought to reverse some of the damage to the Okeechobee ecosystem through wetland restoration and conservation. It is a race against time, complicated by the thousand new residents who move to Florida every day.

Okeechobee County is faced with complex interacting threats to ecological and human systems. Yet the county also has opportunities to implement land stewardship policies that could help it join the ranks of other “naturally great” counties. To this day, large tracts from the original “River of Grass” remain undisturbed. The system represents a valuable ecological reserve that we could safeguard with just a modicum of conservation.

Troubled Waters

At 730 square miles, Lake Okeechobee is the tenth largest lake by area in the United States. It is a shallow lake, whose maximum depth is normally only about 12 feet, with more than 100,000 acres of wetlands along its shores. A set of Army Corps of Engineer channelization projects meant to prevent flooding raises water levels to 15-16 feet during the rainy season. This artificial water level rise has submerged wetlands, killed bird nestlings, and threatened habitat for other wildlife. Furthermore, runoff from leaky septic fields and agriculture has increased the lake’s nutrient content over 400% of the level the lake can safely assimilate. Combined with summer water temperatures in the high 80’s, such high nutrient loads produce cyanobacterial blooms that threaten wildlife and human health.

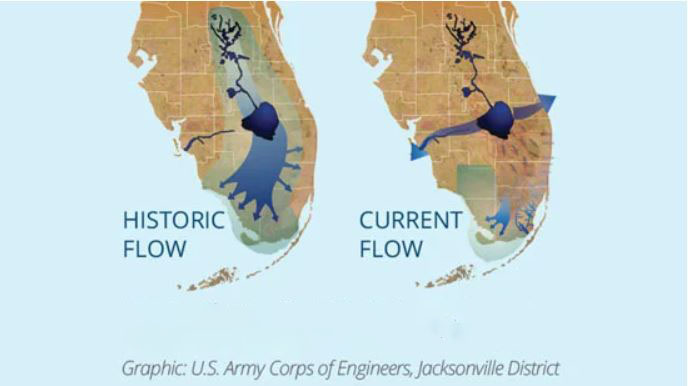

This pattern of wetland degradation extends throughout Florida’s Heartland, including hundreds of square miles of wetlands north of Lake Okeechobee. Formerly, these wetlands would have absorbed the surface water and nutrients before flowing southward through the Everglades. Now, channelization has created agricultural lands for grazing and sugar cane, producing outflows laden with phosphorus and nitrates. These flow to both the Gulf and Atlantic Coasts via the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie Rivers. The outflow creates red tides that are lethal to wildlife and hazardous to people living on the coasts.

Historic and current flow of the Kissimmee, Okeechobee, Everglades watershed (Captains for Clean Water, Key West Express).

Kyle Graham, ecologist and Senior Program Manager at Ecosystem Investment Partners, likens the state of Florida’s Heartland wetlands to a dysfunctional kidney and bladder. The filtration system established by nature has been damaged; significant measures will be needed to restore its health.

Whether Lake Okeechobee can be saved and the red tides prevented will depend on efforts within the Kissimmee River Basin. Like other counties striving to conserve their ecological resources, Okeechobee County has the potential for substantial resilience. The county has put in place programs to reduce the phosphorous inputs into the lake. This effort is one piece of what Mr. Graham calls “unprecedented investments in water quality” by the state of Florida, exceeding $640 million per year. Some will work by preserving natural wetlands. Others will entail the construction of artificial wetlands that replicate natural processes. Lastly, some will focus on encouraging farmers to implement best practices for managing nutrient runoff.

An Impaired Terrain

Okeechobee County, like many in the Heartland Region, is one of the least populated in the state, with slightly fewer than 40,000 residents. Despite the county’s low population density, its farms are a significant source of soil and water pollution. One of the most potent of these sources comes from decades of nitrate and phosphorous application.

The Kissimmee River, which runs along the county’s western border, provides 60 percent of the water entering Lake Okeechobee. Approximately 70 percent of the phosphorus load entering the lake originates from sugarcane cultivation, livestock production, and citrus operations within the basin.

But Okeechobee County is showing signs that it can transcend its legacy of environmental abuse. It is taking crucial steps to conserve and expand natural filtration processes. This offers hope for a healthy, biodiverse environment to millions of residents. Consolidating these gains will depend on farmers’ ability to implement good land stewardship practices. Proven models exist that, if implemented, could re-establish a healthy landscape.

Intercepting the Effluents – Mimicking Nature’s Services

The Kissimmee Basin Stormwater Treatment Project is a proposed 4,500-acre artificial wetland along the Kissimmee River north of Lake Okeechobee. The South Florida Water Management District approved the project in 2021 and selected Ecosystem Investment Partners to construct and temporarily manage it. This nutrient mitigation project would be the second largest of its kind in Florida, and the largest serving Lake Okeechobee. The completed project will pump river water to the artificial wetland to reduce ten percent of pollutants from Lake Okeechobee.

The artificial wetland will treat nutrient runoff in several basins, including the S-154 Basin in the Taylor Creek/Nubbin Slough Subwatershed of Okeechobee County. Mr. Graham refers to the basin as producing “the hottest draw in the region,” meaning it receives the region’s highest phosphorus load. The wetland is projected to extract 100 percent of the phosphorus entering the river during the rainy season. During the dry season, water from the Kissimmee River will be pumped into the artificial wetland. This will achieve the dual goal of filtering the river water while helping to prevent the wetland from drying out.

The Kissimmee Basin Stormwater Treatment Project is just one of five artificial wetland projects proposed by the state of Florida. It would be the largest to treat the water entering Lake Okeechobee. These projects underscore the importance of creating wetlands to maintain the conditions that keep the Everglades county great.

A Winning Strategy for Conservation

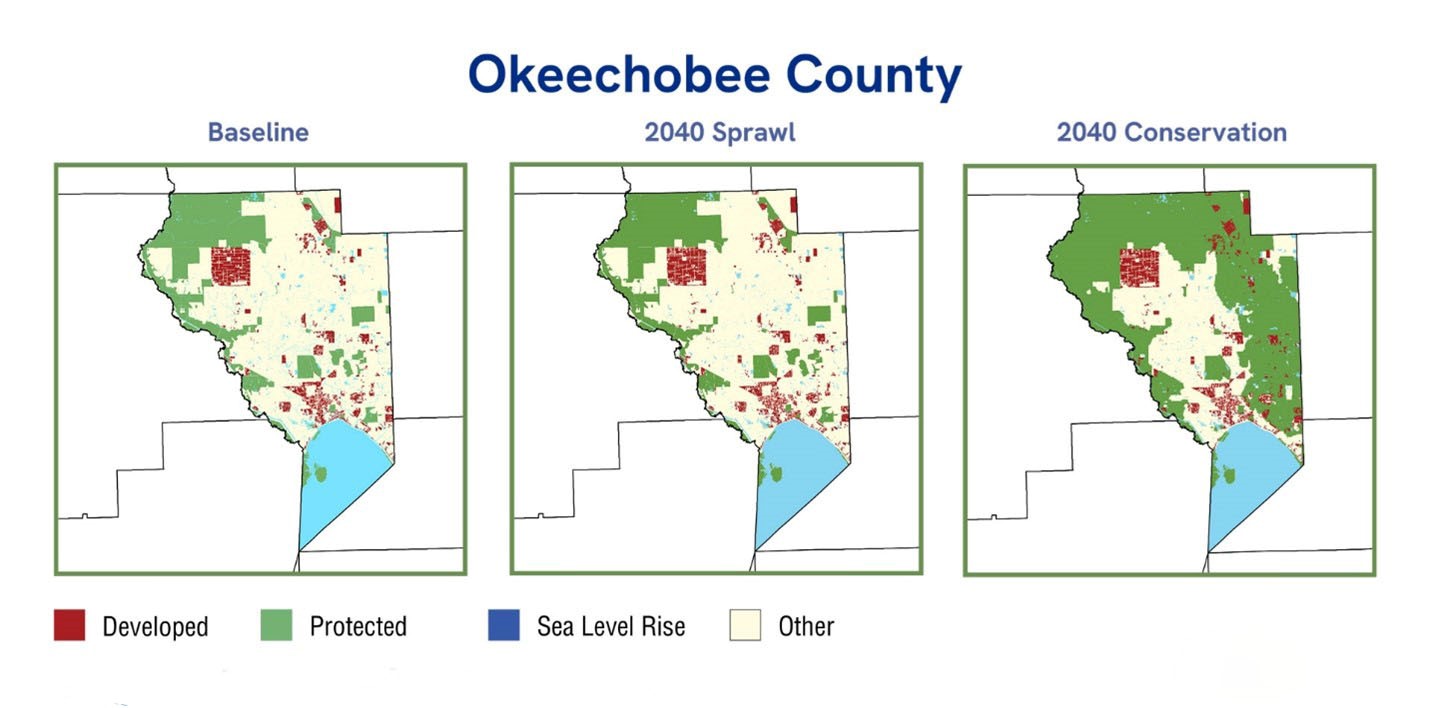

While construction of artificial wetlands is part of Florida’s investment in water quality, the state is also pursuing wetland conservation. At a local level, county land use codes are a key tool in advancing this goal. For example, Okeechobee County’s code allows for the transfer of development rights (TDR) from rural and wetland areas to residential zoning districts to limit sprawl. Very limited population growth of only 4,000 residents over two decades has left large areas virtually untouched, providing additional opportunities for land protection.

Okeechobee County 2040 “sprawl” and “conservation” scenarios (Sea Level 2040 Okeechobee County, 1000 Friends of Florida).

Attempts to conserve remaining open land in Okeechobee County are underway in several forms. The group 1000 Friends of Florida, along with the University of Florida’s Center for Conservation Planning, has come up with an ambitious “2040 Conservation Plan.” The plan would designate 40 percent of the county’s land for agricultural preservation. Together with the natural land targeted for protection, the plan aims to protect 57 percent of Okeechobee County’s land acreage. Furthermore, it would limit development to 400 additional acres over the next twenty-six years, just 6.5 percent of the county.

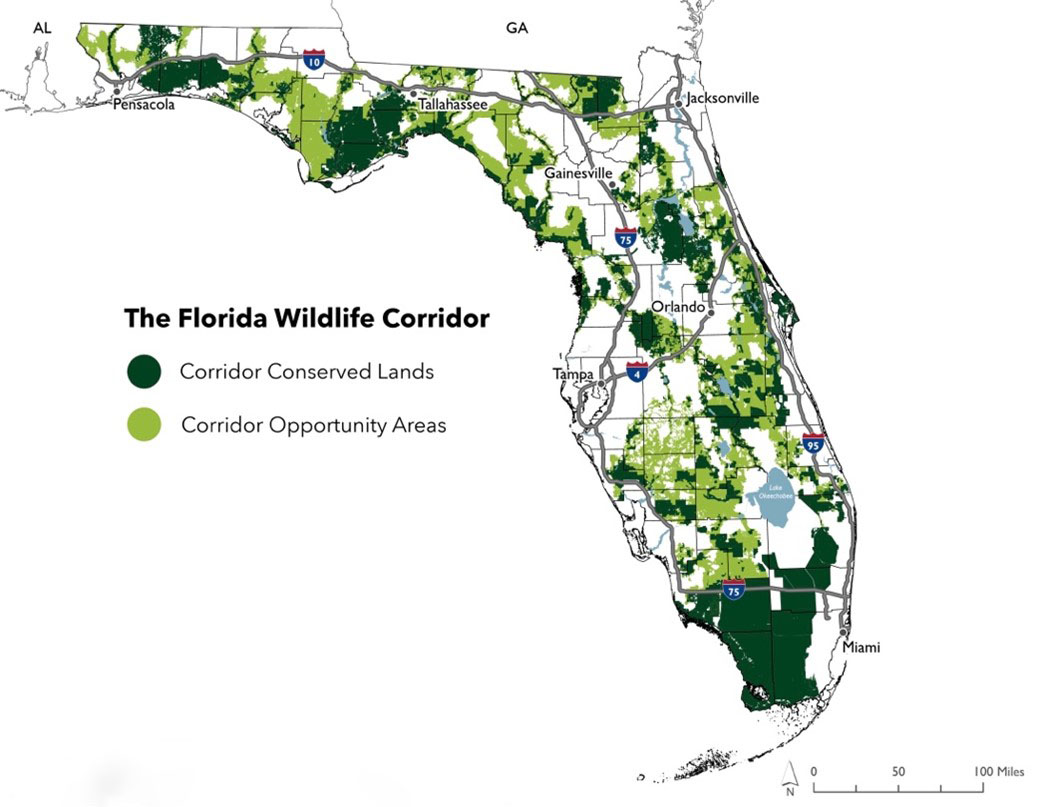

The Florida Wildlife Corridor: A race against the GDP bulldozer (Florida Wildlife Corridor maps, Florida Wildlife Corridor Foundation).

Then, there is the proposed Florida Wildlife Corridor, a sweeping project seeking to establish a continuous ecological corridor across the state. According to the Florida Ecological Greenways Network (FEGN), preserving these undeveloped landscapes is crucial to protecting “Florida’s native wildlife, ecosystem services and ecological resiliency.” State spending on the corridor totals $400 million per year. The money will go toward re-establishing wetland areas throughout the Florida Heartland.

The area slated for protection spans from the Everglades to the Florida Panhandle, or fully one-third of the state. In the fall of 2023, a partnership of the Florida Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Defense, and Conservation Florida succeeded in permanently protecting a 2,526 acre parcel as part of the corridor. In June 2024, the State of Florida completed a further $41-million acquisition of 1,800 acres along the main tributary for Lake Okeechobee.

Opportunities within the Commons

Restoration and conservation projects hold huge promise for repairing the wetland biocapacity of Florida’s Heartland. Engaging farmers with best management practices is essential. Phosphorus runoff reduction programs and payment for ecosystem services are particularly promising approaches.

The 1994 Everglades Forever Act was an important step towards engaging sugar cane farmers in cooperative action to reduce pollution. The Act placed limits on phosphorus runoff from farms. In response to farmers’ input, the Act imposed joint liability on farmers if limits were exceeded. This regulatory framework quickly bore fruit. By 2022, farms had reduced their phosphorous discharges by 66 percent of the region’s 1980’s baseline.

Indiana University environmental social scientist Landon Yoder studied the social context and patterns of cooperation between farmers and state regulators. He found that holding groups of farmers liable is an effective strategy to promote conservation. The sharing of information functions as an enforcement mechanism to encourage adoption of better land management practices.

The Everglades Forever Act incentivized farmer participation through the leveraging of social norms. The act required publicly report pollution levels online, among other measures. Competition to reduce phosphorus runoff levels became a driving force to lower the total nutrient load in the region. As Yoder explains, there is “an individual pride associated with low phosphorous loads.” Today, 90 percent of monitoring points meet restoration goals.

The jurisdiction of the act extends south from Lake Okeechobee. It doesn’t cover Okeechobee County, where cattle grazing rather than sugar cane is the main agricultural land use. Cattle grazing is a lower-intensity agriculture than sugar cane cropping. Still, the area would benefit from extending the Everglades Forever Act. If Yoder’s findings hold true, it should motivate farmers to cooperate to achieve best management practices.

Monetary incentives are another strategy to engage agricultural stakeholders in best management practices for land stewardship. Local farmers care about the land they own, explains Dr. Elizabeth Boughton, Program Director and Senior Research Biologist at Archbold Biological Station. Sometimes all they need is a little help to make sustainable farming practices financially viable. “Many of the farmers are six and seventh generation ranchers, and they feel that land stewardship is very important for a sustaining their way of life. They wish to collaborate to address the problem, and the payment for ecosystem services has proven to be successful, benefitting both the farmers and the ecosystem.”

For example, to encourage Okeechobee farmers to conform to best land management practices, the state plans to pay farmers to hold back water through a system of gates and sloughs. This would reduce the number of man-made surges that currently overwhelm the Okeechobee Lake ecosystem. But if deployed too long, this practice will also increase concentrations of phosphorus in the water. Archbold Biological Station researchers are monitoring phosphorus runoff from farms to determine the optimal schedule of water retention versus release. According to Boughton, there is “a sweet spot of soil saturation” that achieves a balance between flood prevention and excessive leaching of nutrients.

The race to preserve the biocapacity of Okeechobee is gaining urgency as the GDP bulldozer closes in on the county. Much will depend on appreciating and giving space for the natural elements that made the county great to begin with. Wetland restoration and conservation, in combination with agricultural stakeholder best management practices, is a promising model for success.

Dave Rollo is a Policy Specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

This is encouraging – to be honest, I don’t usually associate Florida with policies for conservation, but apparently I have not been paying close enough attention. I hope they continue!

Thank you Dave, I enjoyed this article.

I think that the 1994 Everglades Forever Act imposition of joint liability on farmers if pollution limits are exceeded is brilliant. Oh how I would love it if the developers in Campbell River British Columbia Canada were jointly liable for sediment releases from construction sites and if there was a public reporting requirement.

Question. You noted that in Okeechobee County the 2040 Conservation Plan specifies that:

40% of the county’s land would be preserved for agriculture

17% set aside for natural land preservation.

6.5% additional land for development over the next 26 years

These numbers total 63.5% – what is the use of the other 36.5% of the land base? Do you know how/if the 2040 Conservation Plan compares to the nature needs 50% to maintain ecosystem function?

Cheers, Terri