Pope Francis and the Steady State Economy

by Brian Snyder

Let’s play a game of “who said it.” I’ll give you quotes from either For the Common Good (by Herman Daly and John Cobb), or Let Us Dream (by Pope Francis). You guess who wrote it:

- “…in the wealthier parts of the world, the fixation with constant economic growth has become destabilizing, producing vast inequalities and putting the natural world out of balance.”

- “Then ‘God’ became redundant and disappeared. The human soul alone was sacred. The rest was atoms in a void. For some, the soul too was part of this meaningless physical world; nothing was sacred.”

- “It is not enough to…think in terms of the greatest happiness of the greatest number as if the interests of the majority trump all other interests. The common good is the good we all share in, the good of the people as a whole, as well as the goods we hold in common that should be for all.”

- “…human life is lived most richly and most fully when it is lived from God and for God.”

- “…It is time to explore concepts like the universal basic income (UBI) also known as the ‘negative income tax’: an unconditional flat payment to all citizens…”

You may be surprised that the odd-numbered quotes come from Pope Francis; the even-numbered are from Daly and Cobb. Of course, Pope Francis neither cites Daly and Cobb, nor does he use the term “steady state economy,” yet it’s clear he’s acknowledging limits to economic growth in developed nations. And his message is at least as radical as Daly and Cobb:

When shares of major corporations fall a few percent, the news makes headlines. Experts endlessly discuss what it might mean. But when a homeless person is found frozen in the streets behind empty hotels, or a whole population goes hungry, few notice; and if it makes the news at all, we just shake our heads sadly and carry on, believing there is no solution.

Livable Land, Lodging, and Labor

A few pages later, he lays out a solution, which translated to English is the three L’s: land, lodging, and labor. Francis argues that all humans are entitled to the three L’s, but his use of these terms differs from colloquial use.

Herman Daly educating and edifying with a moral vision of steady-state economics (CC BY-NC 2.0, chesbayprogram)

To Francis, land is not merely the means of production that it is to economists. Land is the earth, and he lays out a biospheric ethic: “We are earthly beings, who belong to Mother Earth… We need now a time of Jubilee, a time when those who have more than enough should consume less to allow the earth to heal, and a time for the excluded to find their place in our societies.”

On lodging, Francis argues we are not simply entitled to a place to sleep, but must be concerned about our entire “oikos” (another word favored by Daly and Cobb), our “house” in a sweeping sense. He argues that we need to build clean, livable urban areas to contrast with the increasingly polluted cities of the developing world.

Finally, Francis argues that labor is a “right and duty for all men and women” but it shouldn’t be just a means of earning an income. Rather, labor should be a means of expression, fulfilment, and contribution to the common good. “Business isn’t just a private enterprise; it should serve the common good.” (“Common good” is another theme of Daly and Cobb; all the way unto their book title.)

Mass Morality

Francis offers a few specifics—he endorses UBI and sustainable development goals, and offers some praise for renewable energy—but Let Us Dream is not a policy paper. It’s derived from an encyclical, intended to clarify doctrine for the largest religious denomination on the planet. Now in the book form of Let Us Dream, Francis sketches the broad outlines of a theological vision with remarkable parallels to “steady statesmanship.”

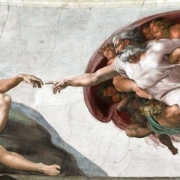

Pope Francis calls implicitly for a steady state economy with human dignity and care for Mother Nature. (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, Monica de Argentina)

Unlike some economists who assume an air of omniscience, Francis writes with modesty, ever clear that he has not all the answers. He knows he’s not God. But he does have a unique pulpit and moral authority. In Let Us Dream, Francis uses that moral authority in edifying prose to clarify that the current economy is ecologically harmful and leaves too many people out in the cold. Therefore, according to Francis, our economic system is immoral and decidedly un-Christian, and we have a responsibility to change it. Further, he clarifies that limiting economic growth in the wealthy world is a major component of the necessary change.

What I find most interesting about Let Us Dream is that it is an almost entirely moral argument. It does not cite dozens of studies about ecological crises, nor does it discuss economic theories or the merits of utilitarianism and deontology. He doesn’t even quote scripture at much length. Instead, to paraphrase, Pope Francis says, “Y’all, this is wrong.” He asks us to simply acknowledge what we all know to be true, what we can all see with our own eyes—that our economy is brutal for many people and damaging to the planet. We don’t really need sophisticated climate models or data from the World Bank to know when something is broken. Francis is asking us to open our eyes, acknowledge what we see, and do something about it.

What Should We Take from Let Us Dream?

For me, it is to stop focusing on the science and economics, at least in public discourse. I don’t believe people will make changes in their daily lives because of the output of an Earth systems model, an integrated assessment model, or any other 21st century means of counting angels on heads of pins.

People know Earth is a mess and they know the economy is a disaster; they don’t need to be convinced. They need to be motivated. I’ve sat through a lot of science, and I have never once left a lecture motivated to do anything but weep or sleep.

Thinking back to the periods of change in the past—Civil Rights, Abolition, Prohibition, Women’s Rights—people were motivated to march, to vote, and more importantly to reconsider the status quo by witnessing suffering around them and through the media. These people were led by religious clergy and laypeople, not scientists and economists.

Of course, steady-state economics has always been deeply linked with religion, or at least Christianity. Daly and Cobb discussed the religious justification for the steady state explicitly, as the even-numbered quotes illustrate. But that religious justification has been subsumed by scientific reasoning. Francis exposes that as impotent human folly.

Brian Snyder is an assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences at Louisiana State University and a CASSE chapter director.

Brian Snyder is an assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences at Louisiana State University and a CASSE chapter director.

"Rappahannock County Courthouse" by taberandrew is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

"Rappahannock County Courthouse" by taberandrew is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Excellent article Brian, Everyone without a vested interest intuitively knows the world economy is totally broken and beyond repair in its current form, so to focus on the intuitive, by opening our eyes (and our minds, of course), as the pope is doing, may motivate a lot more people than the pure scientific argument. Love your line “I’ve sat through a lot of science, and I have never once left a lecture motivated to do anything but weep or sleep.” – it hits the point home nicely.

Paul, UK

With COP26 in the news I’ve been listening to reports this morning of The Pope looking for leadership for sustainability and fairness and Arnold Schwarzenegger calling for more ‘green growth’.

I also listened to a book writer introducing his book about anxiety management.

The book explained that its easy to be fearful of day today things that bring on anxiety, and as an aside its not usual to be fearful of things like climate change that don’t directly affect us right now, it goes that we don’t panic about it or lose much sleep, that’s why its slow to be dealt with. Fear is a powerful emotion that protects us and ensures we perform when its critical.

The Pope, doesn’t profess to having the solution, Arnie, more self assured, he swapped out the Hummer for a more powerful electric, green growth, green jobs, lets go!

Its said that all politics are local, for me, everything is localised to individual decisions. Its not going to be wholly solved by global leaders. Leaders good and bad, come and go. For lasting change its about what’s in the hearts and minds of the individual decision takers. Its about improving the quality of those decisions across all cultures.

With no immediate fear there will be little immediate action.

The only idea for hope that I see is to harness the power of app technology, build a voluntary system of ‘visible to all’ reputation building for ethical consumers. Ethical efficient consumption voluntarily displayed for all to see. (Non co-operators notable by their absence.) Individuals can benefit from a good reputation, social fitness, employment prospects. Let’s then have a look at Arnies air miles and judge for ourselves. Who’s guzzling gas or who’s cycling. Check who’s supporting Amazon or supporting a local world improving Co-op. We can engineer a system where individuals are happy to build, and fearful of losing their reputation. Then we will see the power individual responsibility. Together we have the power to change everything.

I tend to agree – what’s struck me in the last two years is how *ineffective* global leaders are. To be blunt, it seems to me (in a US context) that most people, even conservatively inclined citizens, are broadly ready to get serious about things like climate change. However, elected leaders are if anything pushing back and dragging their feet. I fear that in Anglo-Saxon democracies in particular, political leaders weight campaign contributions and lobbying efforts at about 2/3, and the general citizenry at about 1/3.

I’d have to think about the app idea (very interesting), just since I like to take my time in evaluating things like that. Cautious me :) But overall, this may end up with the general population leading the way, while democratically elected leaders fight a rearguard action to protect fossil fuel industries and so on. It’s bizarre, but I have a hunch that’s how it’s going to play out.

I knew Pope Francis was a different kind of pope, but really didn’t appreciate how different until reading this article. Very intriguing, and very promising. I’m hoping the mainstream media picks up on this a little more as well.